The night in Pike County, Ohio, doesn’t roar—it holds its breath. On those winding backroads where the tree line folds over the asphalt like a ribcage, a cruiser’s headlights cut a pale tunnel through mist, and porch lights glow like faraway buoys. It is spring in the United States—April 2016—and the fields wear the color of new promises. In the Rhoden family’s world, doors are often left unlocked because trouble, for generations, has known better than to knock. By dawn, eight beds will be empty. By noon, four homes will be wrapped in tape. Before sundown, a county will learn what it feels like to have the air changed on them—swept clean of sound and then flooded with sirens.

The Rhodens are the kind of American family that makes rural Ohio feel inevitable: a network of small houses and modest trailers close enough to reach in a few minutes on foot, near enough to borrow a wrench without asking twice. Closeness is currency here. Chris Rhoden Sr. has the hands of a problem-solver and the patience of one, too. His brother, Kenneth, is plainspoken and reliable; you don’t need to wonder whether he’ll show up—he does. Chris’s son, Frankie, is already a father and behaves like one: protective, too young for the weight, but already walking as if he was born carrying it. His fiancée, Hannah Gilley, treats family like a project she’s delighted to keep improving. And there’s Frankie’s sister, Hannah Rhoden, still a teenager, already a mother herself, hair caught in elastic and future pinned to her sleeve. They hunt, fish, fix, trade shifts, share meals, bicker, make up—rhythms that make sense out here where the mail runs late and the sunsets run long.

In a county where everyone knows everyone’s middle name, good news and gossip travel at the same speed. Over months, a particular rumor has been drifting in the same conversation as the Rhodens: tension with another well-known Pike County family—the Wagners. The thread is familiar in small-town America: a relationship that became a co-parenting arrangement; a daughter named Sophia whose birth braided two families together; custody terms that turned into battle lines. Jake Wagner once dated Hannah Rhoden. They share a child. What should have been a negotiated schedule becomes, for some, a crusade. People heard whispers: about who gets to decide what the little girl wears, where she spends the night, which house is “good influence” and which isn’t, who gets the final word. Most times, these disputes scorch hot and then cool. Life in Pike County teaches that you can dislike a person and still wave from your truck. No one imagines a custody dispute blossoming into an atrocity.

April 21 slips into April 22 the way most nights do—quietly, with coffee cooling on counters and TV screens going dark. The air has that Appalachian stillness that lets you hear the wind change its mind. Past midnight, somewhere between goodnight and daybreak, a plan that has been incubating in another household takes shape like a storm. Four homes. Four scenes. The kind of coordination that reads like choreography when you see it written out afterward.

At Chris Rhoden Sr.’s place, the door is the sort that has greeted family more than cops. Inside, a bed holds the man who anchored a sprawling clan, the way foundations hold houses you walk by without thinking. Shots in the dark do not yell; with the right tools, they sound like a door closing in another room. Gary Rhoden is nearby. Two men who fixed things for others cannot fix this for themselves.

Across Pike County, Frankie’s home is soft with the leftover warmth of a family awake too late. He sleeps. Hannah Gilley sleeps beside him. Their toddler son is in a small room with smaller furniture where light switches hang just out of reach. A burst of motion at an hour that makes no sense, and then—nothing. The blanket still covers what it cannot protect. Down the road, where Hannah Rhoden lives, there’s a baby not yet old enough to keep memories, lying so close to her mother that the world’s worst fact—this—the world refuses to register it in real time. And at Kenneth’s, the night is the same as a thousand others until it isn’t.

When the first call comes in, deputies expect one scene. Rural law enforcement knows what a domestic disturbance sounds like, what a bad argument leaves behind. This isn’t that. As units bounce down Pike County’s roads, a map of grief begins to draw itself—house by house, body by body. Eight victims. Multiple addresses. Three young children left alive at separate scenes: a newborn tucked beside a mother who will not wake, a toddler wandering a house, a baby breathing softly in a room that doesn’t know yet how to hold silence. Even for veterans, the scale is a shock to the system. Sheriff Charles Reader, who does not rattle easily, admits to cameras and microphones what the uniforms all understood the minute they grasped the number: this is unlike anything their department has ever seen.

In the hours after discovery, chaos wears the mask of order. The Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation establishes a command center. Agents in plain clothes knock on doors because out here knocking is still how you ask questions. The FBI rolls in because coordination across agencies is the only way to harvest every usable thread. There are checklists you follow after mass fatality events, but checklists do not anticipate the feeling of being outnumbered by the quiet. Crime scene techs move deliberately, labeling shell casings, lifting prints, collecting stray fibers. But what they find as much as what they don’t begins to shape the theory. The scenes are astonishingly clean for what happened inside them: no careless cigarette butts, no thrown beer cans, no DNA on a doorknob crying out I was here. The killings are what investigators call targeted, not random; methodical, not panicked; executed with control most crimes do not possess. Doors show no signs of violent entry in some places, which suggests the kind of familiarity that turns locks into suggestions. And above everything, one unnerving detail hovers like a principle: the children were spared. That choice is not accident. It’s design.

Pike County, Ohio, knows how to talk in circles until a story sits down. The rumor mill runs on gasoline and guesses. Some point to marijuana—grow operations noted on properties that had been raided a few years back, talk of cash, talk of crops. Others resurrect old feuds that never truly died in counties like this, where grudges are inherited along with toolsheds. In a press conference, officials say what they can say: the victims were likely targeted. Everyone else hears what that means: whoever did this was not a stranger driving through on the wrong night.

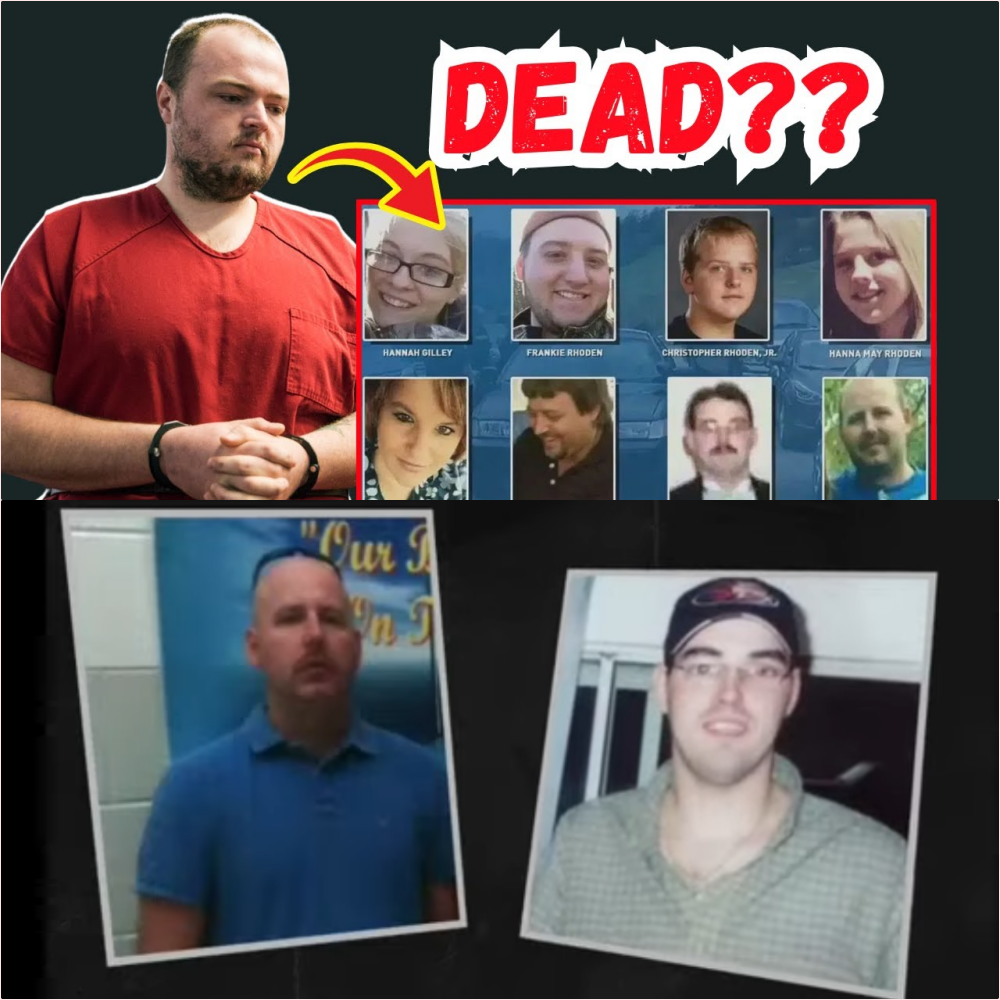

What makes an investigation like this so hard, beyond the miles and the manpower, is the intimacy of wrong answers. The net that includes “people who might want to harm the Rhodens” is the same net that holds their friends, kin, and neighbors—the folks who help each other move sofas and dig posts. Detectives find themselves writing down names they’ve heard in local diners and feed stores for years. Among the names, a family already tied to the Rhodens by history and a baby girl: the Wagners—parents Angela and George “Billy” Wagner III, their sons George Wagner IV and Jake Wagner. The Wagners live a little apart from town, the kind of farm property that can swallow a secret for a season. Their reputation is of a clan that prefers to operate within its own orbit. They are not unknown; they are simply uninclined to be known.

In the weeks after the killings, the Wagners answer questions the way people who believe themselves above suspicion answer questions: carefully, without panic, without too much detail. By year’s end, they sell their Ohio farm, pack up, and relocate to Alaska—a move that, from one angle, looks like fresh air and, from another, looks like distance. Law enforcement does not build cases from vibes. They build them from data. So they collect.

The Ohio BCI, with help from federal partners, scours Pike County and everything that touches it. They get search warrants that allow them to look at what people buy and when they buy it, to see who calls whom and from what cell tower, to track cars with cameras that never sleep. They pull video from gas stations and farm stores; they sift through convenience store footage like panning for gold. They examine the Wagners’ property before the move, polite as a search warrant demands, and carry away objects nobody noticed until someone did: devices consistent with homemade suppressors, the kind of thing a committed hobbyist could assemble from legal parts if he read long enough and cared little enough. They find indications of forged documents drafted to shape a custody outcome before any judge could. They collect receipts that, lined up end to end, trace a shadow over months—ammunition, parts, late-night drives to nowhere, purchases that tally to something more than hunting season. Each item by itself is a dot. The state’s job is to connect them.

What separates rumor from indictment is an accumulation—and time. The Wagners’ move north does not absolve the South. In Alaska, they are watched as carefully as if they had never left Ohio. Meanwhile, back in Pike County, agents return again and again to the same interviews. Human memory is a messy document, but when a person tells the same story twice in the same words, it hardens in a detective’s notebook. When people change the words, it hardens faster. Friends recall the way the Wagners had grown more closed-off in the months before the murders; family notice how conversations around custody had sharpened from argument to ultimatum. The narrowest theory—about Sophia and who gets to decide for her—becomes the organizing principle investigators cannot ignore.

On November 13, 2018, the quiet ends. Ohio authorities stand at microphones and say the names out loud: Billy, Angela, Jake, George IV. Arrests are made. The charges are heavy, and there are eight counts that carry a gravity no courthouse can joke away. The phrase “aggravated murder” lands with a thud that turns every head in Pike County and beyond. The state signals it will seek the most severe penalties the law allows. In rural Ohio, some will say this is justice thinking out loud. Others will say it’s leverage. In truth, it can be both.

The court system in the United States is patient; cases that begin with sirens end with calendar math. Defense motions, discovery battles, pretrial hearings—these are the gears a free society keeps well-oiled, and they must turn. In 2021, one of those gears catches. Jake Wagner, the youngest, pleads guilty to eight counts and other charges. The death penalty, for him and for his family, is removed from the table. His words in court steady the narrative law enforcement built and add weight that only a participant can add. He confirms what seemed too monstrous at first whisper: that the killings were born from a custody dispute, from a controlling certainty that another family could not be allowed to shape Sophia’s life; that months of planning and practice drove a plan into a night; that the children in those rooms were deliberately spared. He names how the homes were chosen, how access was achieved, how the timing was set in a window where people sleep deepest. He speaks of homemade silencers like a man listing tools after a job. On the stand, his voice is flat the way admission of this sort almost always is—robbed of theater, bereft of drama, all function.

When Angela Wagner reaches her own agreement with prosecutors later that year, her words fill gaps. She does not claim a role small enough to duck responsibility; she cannot, because the evidence does not bend that far. She describes lists. She describes how you walk a property by daylight to learn how to move through it in the dark. She confirms how documents were forged in the service of a custody victory that would never see a judge. The story that had been shape now has edges.

Trials are less about surprise than they are about assembly. In 2022, a jury in Ohio sits through months of testimony in the case against George Wagner IV. They hear from experts whose job it is to make tiny marks on metal speak; they see tool-mark matches between suppressors and rounds; they are shown receipts that knit a plan to a purchase. They listen to taps and recordings where conversations steer around and through matters nobody names—the language people use when they talk about a thing without wanting to. They see photos that a courtroom will never be able to describe without the word “exhibit,” though for the families they will never be exhibits; they will always be the thing itself. Prosecutors argue that under Ohio law, the hand on the trigger is not the only hand that acts; planning and participation carry their own weight. Defense attorneys do what defense attorneys must: question credibility, suggest self-preservation as motive for cooperation, poke at the seams where narrative could be stitched for advantage. Juries, in the end, do what juries must: decide. In November 2022, the verdict is all counts. The sentence that follows is measured in lives, not years. In 2023, when Billy stands before the court, the record already laid out by his son and wife and by months of expert testimony rises again to meet him. The result is the same for him: a life measured by concrete and bar counts. Angela’s own sentence is long enough to redefine the rest of her days.

If an ending is what a county wants, this is one kind. Court calendars tick. Penalties become daily routines. The Wagners—once a farm family whose name was said in the ordinary ways a community says a name—are now a shorthand no one wants to use. But an ending isn’t the same as peace. In Pike County, grief never leaves; it compounds. The Rhoden properties grow quiet in the way places do when people who keep them busy are gone. Trailers are pulled off land. Houses age in dog years. Weeds occupy what used to be pathways between porches. That laughter you could hear on a good Saturday isn’t just absent; it’s an afterimage.

The children spared—the decision that felt like mercy in the moment has its own long shadow. They are raised by relatives who must be both guardians and translators of a past the children did not consent to inherit. How do you explain that the people who took so much from your life are related to you by a word Americans hold sacred—family. The answer is you do it slowly. You do it with love. You do it with facts. And still, the shadow is the shadow.

The legal legacy of the Pike County case is not only the docket number or the press conferences. It’s the way investigators learned to read rural crimes more like organized operations than drunken tragedies, to recognize how control dressed up as concern can become a project many hands work on. It’s the way prosecutors frame conspiracy when blood ties make non-hierarchies look like families when they are also teams. It’s the way agencies coordinate across time zones when suspects move from an Appalachian county to Alaska in search of distance. It’s the way digital breadcrumbs—the tiny blips of modern life—can be assembled into a path: online orders for parts that should never have been ordered together; late-night searches that make no sense unless you know the ending; cell towers that draw lines across a map like string. This is the kind of case that becomes an academy lecture, a cautionary slide deck with bullets that stand for lives.

For the public, what remains is simpler and heavier. Pike County’s people remember April like a puncture. They remember the funerals—the long lines, the folded programs, the way men who rarely cry found themselves staring at the floor because the ceiling was too much. They remember locking doors earlier, not because locks ever meant much here, but because rituals comfort and comfort is a start. They remember how the case turned the ordinary into suspicious: a truck on a backroad at 2 a.m.; a neighbor who gets more packages than usual; a family that moves far away without a real goodbye. They remember the way the annual commemorations feel—candles lit, names spoken aloud, stories told so the victims are not flattened into a headline. Chris with a socket wrench and a joke he used too often. Dana who loved her kids in the way that makes a person hard to argue with. Gary, Kenneth—men whose absence is now the shape of rooms they used to fill. Hannah who loved animals and sunlight. Frankie who worked long days and still found a way to be the kind of father you admire on sight. Hannah Gilley whose plans did not get less real because they were cut short. The children who were there and kept breathing.

There is shock in the sheer calculation of what happened that night—the rehearsal drives where the Wagners practiced parking where they wouldn’t be seen, the daylight walk-throughs to memorize how a property sits, the lists of names no one should ever write out the way a person writes a grocery run. There is a different shock that settles in later: that this began with a fight over a little girl, with a desire to control her world so completely that the only solution imagined was to remove other worlds. It is the sort of thinking that feels alien until you remember how obsession sounds convincing in your own head. It is the kind of control that calls itself care.

If there’s a single image that holds the county’s heartbreak, it is not a crime scene photograph. It is a living room after the reporters have left, where a toddler’s toy sits under a chair leg because the person who would have reminded him to pick it up no longer can. It is an engine in a yard that coughs once and stops because the man who coaxed life out of stubborn machines isn’t there to tap the carb with the back of a wrench. It is a field fence mended in a way that says the person who did it had time, which means it was done by someone who is grieving. It is the way wind moves through the trees on a night when the only thing you can hear is your own breath.

The nation watched this story because of its scale and stayed because of its intimacy. This wasn’t a faceless act by strangers on a highway; this was a knot of lives tied together by blood and history and then cut by people who shared both. That is why it haunts—because it teaches that danger is sometimes nearest when it feels like home. It asks communities like Pike County to think hard about how control masks itself as love, about how isolation inside a family can turn into insulation from the rules everyone else follows. It asks the rest of us to consider how an obsession can recruit an entire household until it feels less like a decision and more like destiny. It asks law enforcement to remember that the absence of a footprint is not the absence of a foot.

The files in Columbus and Waverly and every office that handled this case will sit on shelves for years, the bankers boxes heavy with interviews where people told the same story twice and then differently the third time; with lab reports where technicians put words to patterns etched in metal; with timelines that look like a child’s art project—colors and lines and dots, and yet tell a terrible, coherent tale. Those files are a monument to relentless work: the sort of investigation that takes seasons, not days, and the kind of patience that America asks from people it often pays too little. They represent a promise: that when something this impossible happens, the system will keep walking forward, however slowly, until the steps of the people responsible match the steps of justice.

Tonight in Pike County, years later, someone will lock a door who didn’t used to. A mother will call a child in from the yard a little sooner. A deputy will drive a road he could drive with his eyes closed and still scan the tree line like he’s new on the job. On a kitchen table, a framed photo will lean against a salt shaker while supper cools. In a prison an entire continent away, a man will look at concrete and know the rest of his life looks like this. In another prison in Ohio, another man will count the same 24 hours everyone else counts and never use them the way he imagined. In a different facility, a woman will think about fields and laundry on a line and remember what it felt like to believe that control would save her family. And in a handful of homes, children who were spared will sleep through the night, growing toward a future held up by people who refuse to let the worst thing be the only thing.

The night in Pike County doesn’t roar. It holds its breath. And then, because everything in this country eventually exhales, it lets the wind move again, through the trees and across the backroads, past the places where porch lights still burn like a promise—that people will keep sitting on steps, keep waving at their neighbors, keep fixing what breaks, keep telling the truth about what happened, and keep insisting that even here, even after this, life remains.