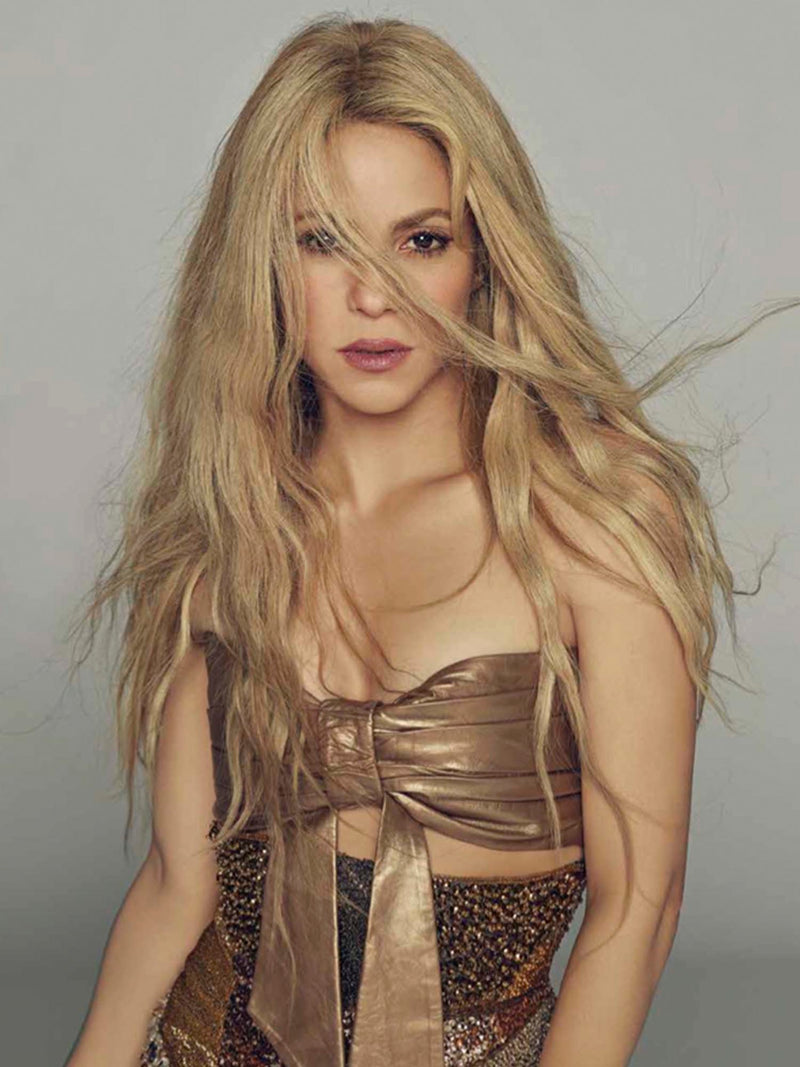

(Courtesy Kayt Jones/RCA Records)

Is there anyone alive who doesn’t have a special, secret fondness for Shakira? Besides maybe that famously angry sea lion who attacked the singer in 2012 and was presumably unaware of her selfless work with the United Nations and had probably never even heard “She Wolf,” because he would have really liked it.

Everyone else seems to have long ago succumbed to Shakira’s hip-swiveling charms. She’s an avatar of pop-culture globalization — a Colombian singer-songwriter of Lebanese descent whose songs are a multicultural grab bag of melodies from the Middle East, Africa, Latin America and, most prominently on her new, self-titled album, the American South.

She’s a social-media giant. Statues have been erected in her honor. (Okay, one statue. Made of metal, not the hand-chiseled marble she deserves. And it depicts Shakira wearing pants she probably would never wear. But it’s a start.)

Shakira has weird, very specific tastes: “Shakira” is not her first album to feature near-lethal doses of reggae and ’90s alt-rock, as if she hasn’t realized that those things are mostly awful.

Yet she also has the broadest canvas of any pop diva in memory — she can contain multitudes, from cumbia to country, and still sound instantly, recognizably like herself.

“Shakira,” her charming, awkward, immensely appealing new disc, tests this theory. It was assembled by a murderers’ row of expensive producers and writers, including Dr. Luke, Max Martin and Cirkut. Any student of recent pop history knows what comes next: dignity-killing, one-size-fits-all dance-pop songs predestined for success and oblivion in the same month.

Shakira submits to Dr. Luke’s dehumanizing ministrations and manages to come out the other end sounding only slightly less like herself. “Dare (La La La)” doubles as the background music for Shakira’s new commercial for Activia yogurt, and it sounds like something Lady Gaga would have made before she became ridiculous. It’s wonderful.

Most of the rest of “Shakira” seems like an uneasy bargain between what she wants (rootsy, often acoustic-based pop with a rangy feel and an affinity for early Alanis Morissette) and what the producers want (hits).

It’s familiar territory for the singer, who has routinely employed of-the-moment production teams to contemporize (and Americanize) her sound, but seldom has the divide seemed so great.

The best tracks split the difference: The new wave/reggae hybrid “Can’t Remember to Forget You” is an energetic duet with Rihanna, pop’s favorite inanimate object.

“Loca por Ti” (one of a handful of Spanish tracks on the standard edition of the album) is ’80s jukebox country, finely rendered. The midtempo Latin pop track “You Don’t Care About Me” recalls vintage Marc Anthony.

Shakira has four fully formed emotions — Reproachful, Cheery, Let’s Dance and I Want to Do Things to You. That’s two more than Dr. Luke usually has to work with, and she also has a voice that’s hiccupy and distinct, especially at the wildest, warbliest reaches of her register. To make Shakira sound like everybody else takes some effort.

Swift is the unlikeliest of specters. But, if only because she is one of Shakira’s few rivals who can credibly deliver a slender love song backed by an acoustic guitar, she also haunts the folk ballad “23,” one of the album’s starkest and best songs.

Shakira has never been much of a lyricist, but “23” is clunkier, and braver, (“I used to think that there was no god / But then you looked at me with your blue eyes / And my agnosticism turned into dust“) than Swift would ever dare to be.

Shakira’s comfort level seems to ebb and flow throughout the album: She’s commanding on the Spanish-language songs, playful on the bangers, subdued on the songs that are obviously ill-suited for her, such as the Nashville ballad “Medicine,” a collaboration with Blake Shelton, her fellow judge on “The Voice.”

It’s one of those duets where two famous people from different genres are joined by their business managers in pursuit of a crossover hit. They sing at each other and both sound as if they’d rather be anywhere else.

Shelton, also at half-wattage, treats her with unusual delicacy, as if he was enlisted partly for his hit-making skills and partly to stop her from running away.