The red coat hung by the door like a target, bright as a warning flare against the Montana winter, and my phone lit up at 5:00 a.m. with my grandson’s name. “Grandma, don’t wear your red coat today,” he whispered, his voice trembling, thin as frost. “You’ll understand soon.”

I didn’t ask questions. Not then. I stared at that cherry-red coat I’d bought in Billings—a practical splurge for dark mornings and snow-blind roads—and I reached instead for the old brown jacket with the scuffed elbows. At sixty-three, you learn to listen to the tremor in a loved one’s voice over the certainty of your habits. Outside, the prairie sky was the color of old steel, the air clean and sharp the way winter air is in the American West. I poured coffee with hands that felt too steady for the dread crawling up my spine, and when the clock ticked past nine, I started down the gravel road toward the county bus stop, the same routine I’d kept since Frank died: bus to town, groceries, lunch at Betty’s Diner, home by three. Predictable. Ordinary. Safe.

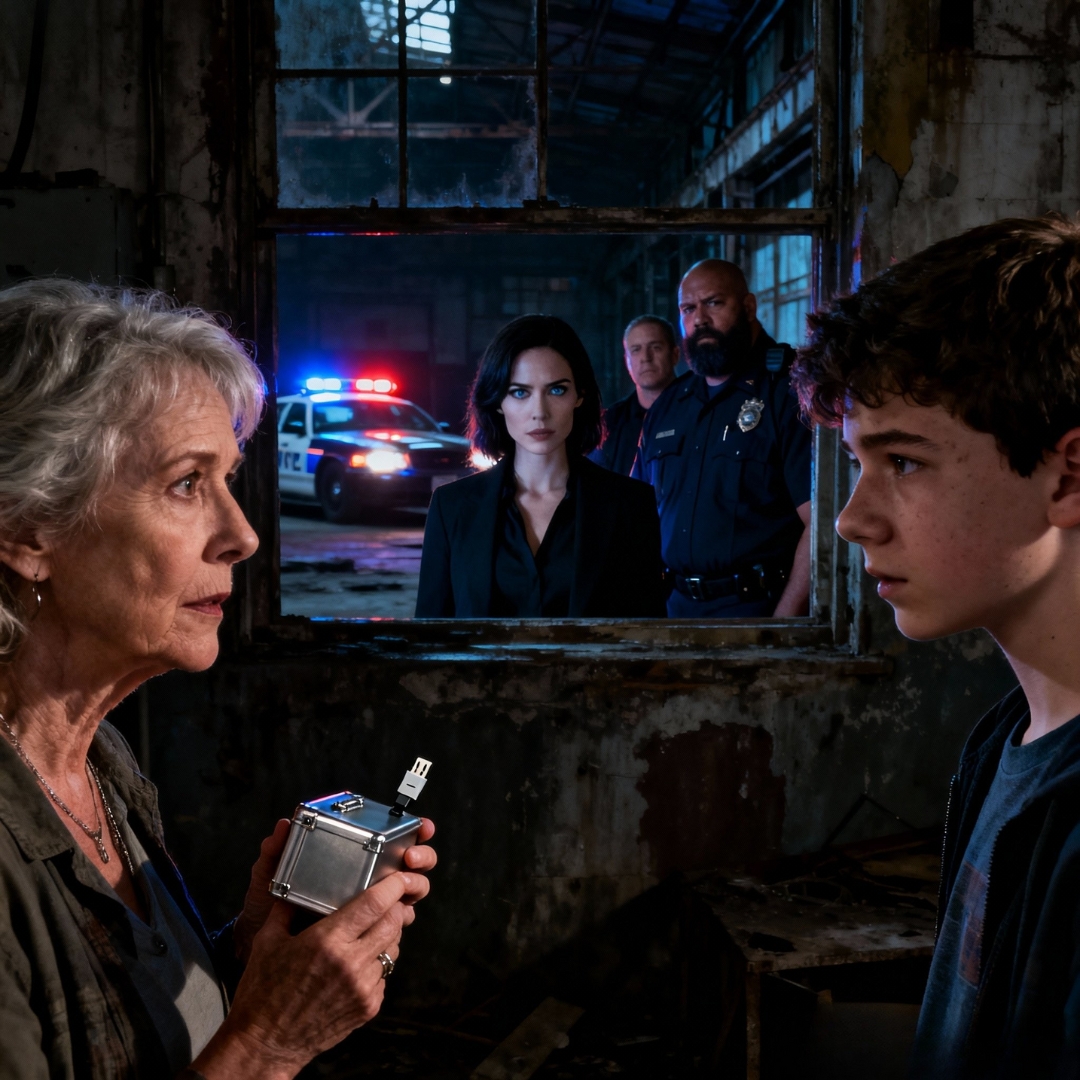

Only when the bus stop came into view, I stopped cold. No bus. Four patrol cars, their lights washing the morning in red and blue. A length of yellow tape snapped in the wind. Detectives in cold-weather jackets moved with purpose around the shelter where I’d stood a hundred times, reading library books with chapped hands while the wheat fields rolled off toward the mountains.

Sheriff Tom Brennan—tall, gray at the temples, the kind of solid a small American county depends on—lifted a hand. “Mrs. Foster,” he called, voice professional, not neighborly. “I need you to stay back, please.”

“Tom,” I said, and it came out thin. “What happened? I need to catch the bus.”

“There won’t be a bus this morning.” His eyes, kind eyes I’d known since high school, had the hard shine of duty. “There’s been an incident.”

“What kind of incident?”

“A body, Mrs. Foster. Found here around six.”

The world tilted. The breath left me. “Who?”

“We’ve just identified her,” he said, careful. “But—Alexia, she was wearing a red coat.” He glanced toward the shelter, toward a white tarp that made the day feel obscene. “Cherry red. Like yours.”

Something old and iron rang inside me. My grandson, Danny, calling at dawn to beg me not to wear red. My coat bright enough to be seen from a mile away. The bus stop where I always stood on Tuesdays and Fridays. I must have swayed because Tom’s hand found my elbow. He eased me onto the hood of his cruiser. The engine ticked in the cold. Far off, a hawk cut the sky into neat, merciless lines.

“Tom,” I managed, “Danny called me at five. Told me not to wear it. Said I’d understand later.” I watched his face snap from concern to focus. The pencil came out. The notebook opened. I told him exactly what my grandson said, down to the last breath on the line.

“Where is he now?” Tom asked.

“I don’t know. He sounded scared.”

“Scared of what?”

“If I knew, I wouldn’t be sitting on your patrol car.”

Detective Roxanne Mirik approached—dark hair pulled tight, tired eyes that missed nothing. She listened, took notes, asked for my son’s address in town. They spoke into radios, low and urgent. Then Tom’s radio crackled hard, and whatever he heard made the lines in his face deepen like someone had carved them with a blade.

“Say that again,” he said.

He lowered the radio and looked at me as if I’d set a fire on purpose.

“Alexia,” he said, voice careful the way you speak to dynamite, “we ID’d the victim. Her name is Rachel Morrison. County Records. According to her phone, she’s been in contact with your grandson for two weeks.” He paused, just for decency. “We also found a document in her coat pocket. A property deed. To your farm.”

“That’s impossible,” I said, and for a second I believed it. The farm had been in my family for four generations. We grazed cattle through recessions and planted hay the year the early freeze broke our hearts and we kept going because that’s what you do out here. “I didn’t sign anything.”

“This deed says you did,” Tom replied. “Dated last month. Recorded three weeks ago. It says you transferred the property to your son, Robert, and his wife.”

I gripped the edge of the hood like a railing. My breath steamed and disappeared. Of course Vanessa would do it with a pen. My daughter-in-law always had a brochure, a plan, a notarized form ready at dinner. Sign here, Mom. Just an insurance update. Sign here, Mom. Just a consent form. She worked in real estate. She breathed paperwork.

A car idled behind the cottonwoods down the road, half-hidden, engine ghosting the air. Dark blue sedan. The driver watching. I looked hard and felt a cold that wasn’t weather. Vanessa. She didn’t wave. Didn’t smile. Just slid her sunglasses down, met my eyes with an expression I couldn’t name—victory? warning?—then eased away like the morning was over and she had errands.

“Tom,” I said. “I think I know where to start.”

At the sheriff’s station, the fluorescent lights hummed like they were keeping secrets. Coffee smelled burnt and loyal. I told the story again into a recorder, each word landing like a nail: the call from Danny; the coat; the stop; the deed. Detective Mirik asked if I’d had conflicts with anyone. I said we weren’t that kind of family. Then I revised: we weren’t that kind of family in public.

Sunday dinners had turned into board meetings with canapés. Vanessa would slide documents across my table between meatloaf and pie, asking me to sign this, initial that. “It’s safer,” she’d say, smiling like the commercials. “It’s efficient.” My son, who’d been charming and backbone-light since birth, would say, “Mom, Vanessa knows this stuff. She’s helping.” And I would sign the things that made sense—insurance, emergency contacts—and slide back the things that smelled like loss. I would always, always hand the pen to Danny first to play with, to buy myself a moment. That delay might have saved my life.

While the detective stepped out to answer her radio, Tom said softly, “Alexia, when’s the last time you wore the red coat?”

“Yesterday,” I said. “Book club.”

“How many people know you take that bus at nine-fifteen?”

“Half the county.”

He nodded. The pencil stroked paper. Outside the interrogation room’s small window, the snow-dull morning brightened by degrees like someone turning up a dimmer. Tom’s jaw tightened as he listened to something else through his earpiece. “Rachel’s boss confirms she processed a deed on your parcel,” he said. “We’ll get the file.”

“Check the notarization,” I said. “Check the witness lines.”

The door opened. My son, Robert, stood with a man in a tailored suit whose hair belonged on TV. I felt relief so sharp it hurt until the suit stepped forward, hand out, smile preloaded.

“Peter Mitchell,” he said smoothly. “Ms. Foster, I’m your attorney.”

“I didn’t hire you,” I said.

“Robert did. Proactively.”

Robert looked small and flushed and like a man who has rehearsed a speech in the car and forgotten his lines. “Mom, just—don’t say anything,” he pleaded. “Not until Peter—”

“I said I didn’t hire him,” I repeated. “And I’m not under arrest. I’m giving a statement.”

Peter Mitchell’s smile didn’t budge. “And I strongly advise you to stop. Sheriff, unless you’re charging Ms. Foster, we’ll be on our way.”

Tom’s eyes flicked to mine: Do you want to leave? I shook my head. “Not yet,” I said. “Robert. Look at me.”

He did. His eyes were bloodshot. He looked like a boy again. “Did Vanessa bring you a deed to sign?” I asked. “In the last month.”

The pause was a confession. “She—she mentioned having a plan,” he stammered. “Said it would protect you. Said the farm should be in our names to avoid taxes. I told her you’d never agree. I told her—Mom, I swear on my life I never—”

“Stop,” I said. “I believe you.”

Because I did. Robert was a leaf in a current. He’d always float wherever the water moved him. Vanessa was a dam.

Back at the farmhouse, the horizon wore the Rockies like a crown and the wind ran its fingers through the dry grass as if checking pulses. Robert pulled into my gravel driveway fast enough to spit rocks. In the kitchen, the light fell across the table where the deeds and the bills and the birthday cakes had all spread themselves for decades, and there she was: Vanessa, in my house, going through my filing cabinet with surgical focus. She closed the drawer the way a person closes a deal and turned with a smile that had sold more properties than truth ever could.

“I’m helping,” she said brightly. “Looking for documents that can clear this misunderstanding up.”

I thought of my red coat. Of the body under a tarp. “Did you forge my signature?” I asked. “On a deed. On anything.”

She blinked, slow, offended. “How dare you,” she said like I’d broken into her home. “After everything I’ve done for this family.”

“Say yes or no,” I said. “It’s legal language. You know it.”

“Legal language?” She laughed without moving her face. “Alexia, you don’t even—” Her voice sharpened. “This is what comes of refusing to adapt. The world changes. You cling to this land like a life raft, and it’s drowning you.” She looked at Robert, not me. “She’s not safe out here alone. She’s not competent.”

“Leave,” I said.

“Not until you admit—”

“Get out of my house, Vanessa.”

The thing behind her eyes flashed. She smoothed her coat, straightened, and spoke very calmly. “You should know that the deed is recorded and the signature notarized. In this state, that carries weight. Whether you remember signing or not doesn’t change its validity.” She touched the back of my chair like she was blessing it. “We’ll talk again,” she said. “In court.”

She left. Robert sank into the chair she’d touched and covered his face with his hands. “I’m sorry,” he said. He’d said it a thousand times in a thousand small ways over the years, but this one counted. “I didn’t see. I should have seen.”

“You loved your wife,” I said. “It’s a rotten trick vulnerability plays that it tastes like loyalty.”

The text came at dusk, from a number I didn’t know. Grandma, I’m sorry. Meet me at the old mill at midnight. Come alone. Then the words only we knew: Remember the strawberry summer.

Some codes don’t look like codes until you need them. When Danny was seven, we planted a strawberry patch behind the barn because Frank insisted children are supposed to grow something they can eat. We picked till our fingers stained and our stomachs revolted and we laughed like people who believed in July forever. Strawberry summer, we called it. That phrase was a vow.

Robert begged to come. I told him no. He begged again. I reminded him: Sometimes a mother’s strength is saying no to her child for the good of his child.

On the road to the old Clearwater mill, a pair of headlights slid into my rearview mirror and stayed there, a patient shadow. This is a thing you learn in big-country America where empty roads tempt both good and bad men: who follows to harm, who follows to protect. These were neither. These were professional.

I killed my lights and took the logging road Frank and I used when we hunted antelope before his heart betrayed him in his sleep. The truck groaned. Branches scraped like fingernails. The headlights on the highway slipped past; then braked. I pushed deeper and let the dark swallow me whole. When I came out the other side and found the highway again, I was alone. I parked with my hood pointed at the exit. I texted Tom: Meeting Danny at the mill. Feels wrong. If you trust me, listen in.

The mill rose like an American ruin: a four-story monument to industry and exit plans, petrified against the rushing river. My flashlight caught dust like snow. “Danny?” I called, low.

He sat on a crate, thinner than he’d been three days ago, eyes raw, cheeks hollowed by fear and a kind of grief I recognized—not for a person gone, but for a person never real.

“Grandma,” he whispered, and folded into my arms. His body shook, and I understood more than he said right then. There are truths you read by touch.

He told me everything in pieces, the way kids confess to breaking a window and then admit the ball was planted: He’d met Rachel at a coffee shop. She worked at County Records. She asked about the farm. Said her grandmother’s land had been stolen by developers. Said she wanted to help protect ours. She’d been charming in the way that’s really just study. He’d believed her. Then, last week, he’d followed her after seeing her with Vanessa. Two hours at a downtown restaurant. A conversation full of secrets he couldn’t hear but felt anyway. When he confronted Rachel, she laughed and called him a useful idiot. She said Vanessa hired her months ago to target me, to map my habits, to make the paperwork easy. She said she had everything backed up: emails, records, recordings. She’d blackmail Vanessa forever.

“Why warn me?” I asked.

He pulled a small drive from his pocket. “Because she was scared,” he said. “She called me at four-thirty this morning. She was crying, said someone was following her, said she took your red coat from the mudroom Sunday to get your attention at the bus stop. Then the line cut.” He swallowed. “She asked me to warn you if she couldn’t.”

“And this?” I held up the drive.

“Her insurance. Part of it. But the last folder is encrypted. I can’t crack it. Rachel said it’s the most important part.”

Footsteps below. Multiple. Trained. A voice: “Mrs. Foster? Sheriff’s Office. You in there?” Not Tom. A deputy, younger. My flashlight found a badge. Deputy Marcus Hall.

“Tom sent us,” he said. “Your son reported you missing.”

“Then why are you creeping like a raccoon?” I asked.

“We didn’t want to spook your grandson,” he said, and his hand hovered near his weapon in a way that had nothing to do with protection.

“Because,” a familiar voice said lightly behind him, “we needed to see what you’d bring out into the open.” Vanessa stepped forward, dressed not like a realtor now, but like someone who did her own dirty work when the help got sloppy. Two men flanked her, big shoulders under bigger jackets. Deputy Hall didn’t move. He’d already chosen a side.

“Hello, Alexia,” she said. “I believe Danny has something that belongs to me.”

Danny slid in front of me. “You’re not getting anything,” he said, voice shaking but brave.

Vanessa’s smile was clinical. “Rachel called you, didn’t she?” she cooed. “Such a dramatic girl. Not built for this line of work. She thought she could blackmail me. She forgot who taught her.”

“You killed her,” I said.

“Please,” Vanessa replied. “I don’t get my hands messy. That’s what cash is for.”

“And tonight?” I asked. “What’s cash for tonight?”

“For signatures,” she said, amused. “You’ll sign over the farm to us willingly, here and now, with a witness.” She gestured at Hall. “Then on your way home, you’ll have a tragic accident on those pitch-black county roads. These things happen in Montana. The wind, the deer—”

My phone was already recording. I lifted it so she could see the red light. “You’re arrogant,” I said conversationally. “That’s your flaw. Not greed. Not malice. Arrogance. You think I got this old by being stupid?”

Her face went still, then flat, then curious. “What do you think you’re doing?” she asked.

“Broadcasting,” I said, and smiled. “To Tom. To the state police. To anyone in this country who still believes in a good courtroom.”

Hall’s hand twitched toward his gun and the door blew inward as Tom came through with three state troopers in winter hats, boots loud on old wood. “Marcus,” he said, voice brick-hard, “hands where I can see them.” Vanessa pivoted toward the window, but one of the troopers was faster. Cuffs clicked. She spat something I won’t stain this page with. Tom lifted his phone to show my face reflected next to an audio wave he’d been listening to for ten minutes.

“You took a risk,” he told me later outside under a sky trying to be dawn. “You always did push your luck in high school, Alexia.”

“You liked me that way,” I said, and for a second we were teenagers again, him in a letter jacket, me in a red ribbon that meant I could outrun boys barefoot in spring.

The good part should have started there. It didn’t. Because the next morning, while the county attorney was drawing up charges, Vanessa made bail—two hundred thousand with cash she’d had ready because of course she had—and her attorney called my kitchen to announce a civil suit against me for defamation and “intentional infliction of emotional distress,” and filed for a competency hearing to appoint a guardian over me.

In the United States, you can be the victim and wake up a defendant. You can be the woman almost killed and find yourself accused of being dangerous to yourself. You can be a farmer who paid taxes for forty years and be told you’re too old to sign your name without a witness. That morning, the coffee shook in my cup.

“Let them try,” I said. I said it like a prayer and like I meant it.

Then came the text that wasn’t from a lawyer: Sign over the farm. Drop the charges. Live in peace. Keep fighting and you lose everything—including people you love. 24 hours.

Threats have a smell. This one smelled like leather seats and printer toner.

Tom’s forensics team couldn’t crack the encrypted folder. Vanessa’s attorney claimed every recording we had was a performance, a frightened woman going along with a corrupt deputy. The civil hearing was set for the next afternoon. I asked Tom for ten minutes with the judge. He said it was irregular. I said so is pretending I’m incompetent.

Danny dug through public records the way a prairie dog digs toward air. Summit Development. Shell companies. Transfers. Elderly owners. Obituaries. Four dead within six months of selling. Two car accidents. One fall. One heart attack. Patterns don’t care about your disbelief.

Then we found Rachel’s real name: B. Hartley. Her grandmother’s ranch outside Red Lodge. Bought by Summit Development six years ago. House burned. Grandmother dead.

“Rachel didn’t just join Vanessa,” I said. “She was a student in a master class.”

We drove to Red Lodge after dark with a patrol car shadowing us like a guardian angel you don’t argue with. The ranch sat quiet—house a blackened skeleton, barn still standing, ribs showing. In the last stall, behind a loose plank, we found a metal box wrapped in plastic. Inside: a note and a thumb drive. If you’re reading this, I’m probably dead. Password: starlight9997.

The clicks of cars pulled up outside like the sound of a decision. Vanessa. Mitchell. Two men with shoulders like doors. “You’re trespassing,” she called, the voice smooth again. “Hand it over.”

“That’s a lot of audacity on a property that isn’t yours,” I said, and lifted my phone to show the Live icon already streaming.

Sirens. This time I didn’t leave room for luck to get hungry. Tom’s convoy boxed them in. The men went for bravado; the troopers went for cuffs. In the flashing lights, Vanessa stared at me like I was a country she’d failed to colonize.

The competency hearing was canceled the next morning. The judge called me himself—a man I’d met once at a charity auction who loved fly-fishing and fairness. He said I’d displayed “exceptional civic courage,” and I wrote the phrase on a sticky note and stuck it to the inside of my cabinet where I keep tea bags and stubbornness. The power of attorney was exposed as a forgery. So was the deed. The encrypted folder opened under the state lab’s hands like a mouth made to confess: six years of recorded calls, emails, scans of signatures, transfers to crooked officials. A video of Vanessa at a table with Rachel, voice low and lazy, talking about fires like they were weather.

The investigation went federal. The headlines were simple, American, made for morning shows and late-night commentary: Elder Fraud Ring Exposed in Montana. Real Estate Scheme Targets Seniors. County Deputy Indicted. Names fell like rotten fruit: deputy, lawyer, clerk.

Vanessa took a plea—life without parole—in exchange for rolling over on the rest of her tower. Her attorney stood in court and sounded like a person describing an unfortunate misunderstanding with mortality. The judge looked at her the way you look at a snake that has tried to convince you it is a silk ribbon. He sentenced her like he was dressing a wound: firmly, without flinching.

Robert filed for divorce with hands that shook like a leaf in a dry wind, and I sat at my table and watched my son reclaim parts of himself he’d pawned in the name of something he thought was love. He apologized until the word wore thin and then he did better, which is the only apology that ever counts. He went to therapy. He started asking how I was instead of telling me what I should do. He asked Danny to walk with him sometimes, no destination, just steps.

Danny took a semester off. He learned the kind of shame that comes from doing the right thing too late and then learned that redemption doesn’t care what time it is; it cares that you showed up. We repaired fences and patched the barn with lumber that looked too new. We replanted the strawberry patch twice as big, because hope is sometimes a math problem.

Spring came to Montana like it owed us an apology. The snow held on in drifts while the sun wrote its name on the fields in gold. The patrol car left the end of my driveway. The mail truck stopped bringing documents that could kill someone. The neighbors baked pies and said they always knew something was wrong with that Vanessa girl, which is the generous lie people tell when they can’t bear to admit they missed it, too.

I went to a restitution hearing at the courthouse in town and sat with other families who’d lost land and parents and pride. A woman my age with gray at her temples took my hand and told me her sister had died in one of those “accidents” and I squeezed and didn’t say anything because what could I say that wouldn’t hollow out under its own weight? We stood when the judge entered and we sat when he told us that money was not justice but it was a start. We nodded like people who understood interest rates and grief.

Tom stopped by sometimes with paper cups of coffee that tasted like community. He stood on my porch and looked out over the fields and told me I scared him and made him proud in equal measure. I told him high school Alexia would have kissed him behind the bleachers if he’d asked right and he laughed from his belly the way men do when they are grateful to be alive and in decent company.

People love an ending clean as a new counter. This isn’t that, and America knows it. We don’t do tidy. We do persistence.

So here is my image for you: a porch in the American West, evening turning the mountains the color of bruised plums, my red coat hanging on a hook in the barn like a retired flag. A boy-not-boy-anymore brings me hot chocolate and says, “A penny for your thoughts,” and I say, “I’m thinking about age.” He grins. “You mean wisdom,” he says, and I say, “I mean the freedom to be underestimated and the pleasure of proving the math wrong.” We sit. We listen to the river and the wind and the sound fences make when they remember their purpose. The strawberry plants push little green tongues through the dirt like hope that learned how to survive frost.

In a few months, we’ll pick until our fingers stain again. We’ll eat too many and we’ll laugh and maybe we’ll get sick. We’ll call it strawberry summer even if it’s July and we’ll call it ours because it is.

If you want the moral, it’s old-fashioned and American: Keep records. Believe the tremor in someone’s voice over the confidence in someone’s suit. Make friends with your sheriff but bring your own receipts. Learn the routes in the dark that let you lose a tail. Plant things you can harvest later. Love your family, but love your boundaries more. And when someone tells you you’re too old to fight, remember that age is a fortress if you know how to use it.

Vanessa thought the red coat made me easy to find. She didn’t understand that a red coat is warning and permission both. I hung it up and chose to live. Then I chose to fight. Then I chose to build again.

That’s the story. It happened out here under a sky so big it makes your sins look small and your courage look exactly the right size. It happened in a county where people still wave at each other from pickups and where the law shows up even when the snow says stay home. It happened in a farmhouse with a kitchen table that’s seen more tears than polish and more signatures than sermons.

And if you need one last line to take with you, make it this: You are allowed to keep what you build.