The envelope was thick and cream, the kind old-money lawyers still use when they want paper to feel like a verdict. It sat on my aunt’s farmhouse table between a chipped mug of diner coffee and a bowl of Michigan apples we bought at a roadside stand off I‑94. Outside, the wind pulled through the corn like it had somewhere to be. Inside, my aunt slid the packet toward me and said, “Read the last page first.” That’s how I found out I was a millionaire—at 21, knees still scuffed from moving boxes into a dorm that smells like bleach and second chances.

The probate stamp glowed like a county seal on a state flag: estate of my grandfather, assets transferred, signatures looping in lawyer script. One million dollars, cash. The rest—one hundred fifty acres and a farmhouse with a porch that knew every sunrise—went to my aunt, who is technically my father’s older sister but practically my first real parent. The official tone of the document tried to flatten history into balances and lots, parcel numbers and account routing, as if money could separate itself from blood. It can’t. Not in this country, not anywhere, but especially not in the quiet heartland counties where wills feel like weather.

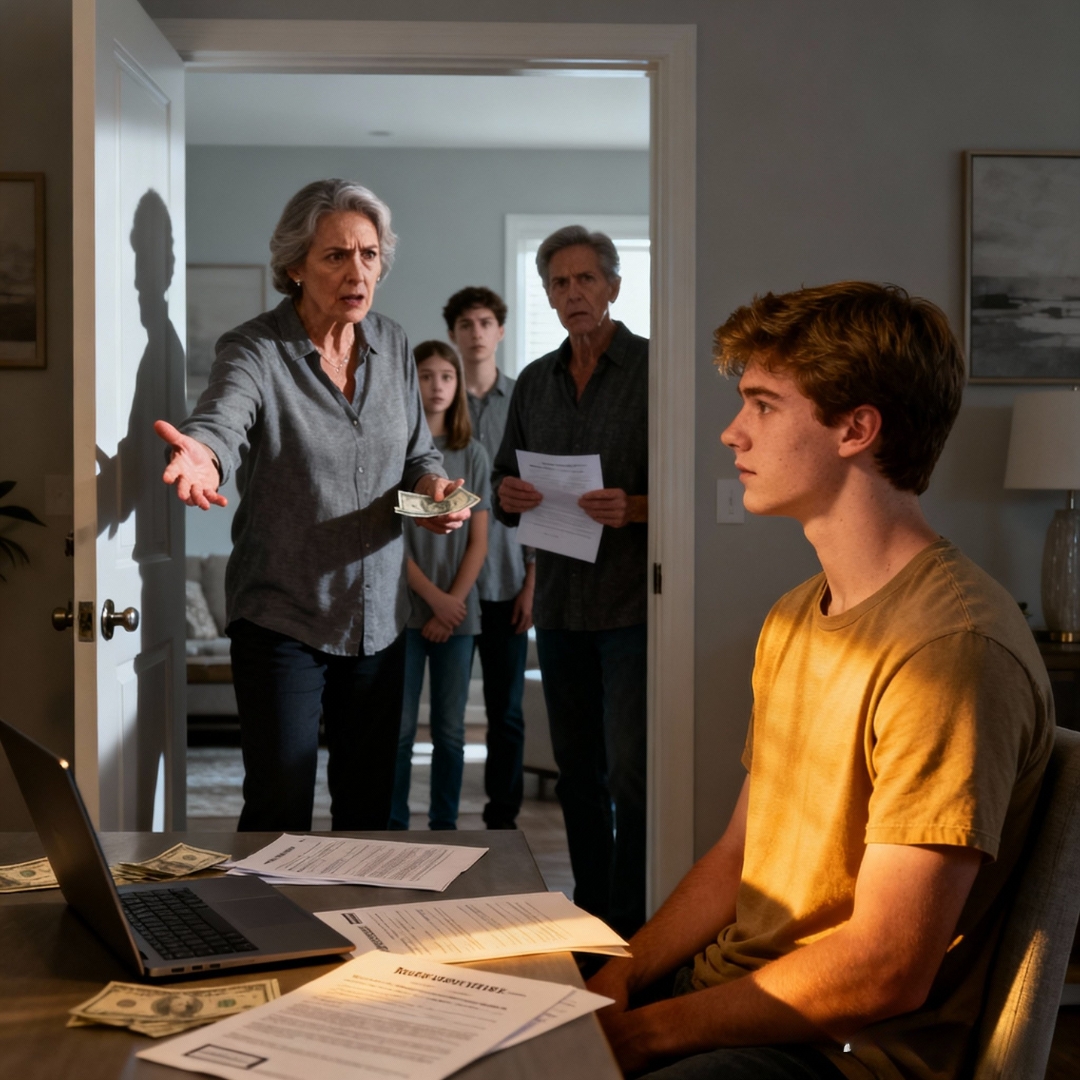

Three hours later, the news found my parents the way gossip finds a group chat: fast, messy, hungry. The voicemails started with sugar and slid toward demand like a car down an icy driveway. “Baby, we are so proud of you,” my mother breathed, as if pride could be backdated. “We should talk about smart investments. Private school knows a guy. Your sister—well, your half sister—she has tuition due.” My father’s message was shorter: “Call me. Important.” Both had the tone of people who suddenly remembered the existence of a son who’d become an asset.

To explain why the phone in my pocket felt like a fuse, we have to drive back to the cul-de-sac where the HOA keeps the trash cans out of sight and the joggers nod without checking if you’re okay. The divorce wasn’t loud. No slammed doors, no broken plates. It arrived like a corporate memo. They sat me on the couch on a weekday afternoon, blinds open to a suburban street that pretends to be neutral. “We’re separating,” my mother said, already careful with her voice. “We both met someone,” my father added, the way a bank officer says “Your application was not selected.” They promised me video games and vacations and two houses close enough to make joint custody look like you can split a person evenly. “We’re only two miles apart,” Mom said, like a distance that small could make a child’s heart do math.

I was eleven with big ideas about what divorces look like—shouting, a slammed screen door, split holidays, a dramatic court date with a gavel my social studies teacher kept in his drawer as a prop. What I got was a “silent divorce,” which is like a slow leak in a tire: one day you’re rolling, the next you’re flat and pretending it’s fine. Mom packed her life into boxes with handwriting I still recognize. Dad’s girlfriend—she insisted on “partner” back then—arrived with twin boys who carried their resentment in their shoulders. In our house, my mother’s bedroom transformed in a weekend. I watched the bedspread change and learned what it looks like when a room forgets you.

The joint custody schedule was a calendar photo op. One week at Dad’s place, one week at Mom’s new apartment, both within two miles, both filled with people who had reasons to act like I was a guest. Mom’s boyfriend liked to hold hands in the hallway and looked surprised when I rounded the corner. Their public displays of affection were public to me in a way that made walls feel like glass. They took me on a two-day trip once where the hotel balcony became my assigned seat while they “caught up” inside. I was twelve and still knew the shape of what I was hearing through a sliding door.

At Dad’s, the twins held the house like territory. They were good at it. When I got tall enough to start eating seconds, they turned their complaints into a performance. “It’s our weekend,” one said to my father, and my father learned the art of the deferral: “Skip this one. Next week.” Next week is a flexible concept when your parents live two miles apart and you are convenient only when there’s an empty space in their plans. I wore out sneakers walking between houses where I was never in the photographs.

Here’s the math no one talks about when they sell you the kindness of a “silent divorce”: all the noise goes into the child. You learn to smile without becoming a person who can be pulled into a hug. You learn to travel light. You learn what never to ask for because the answer becomes a weapon later. When the next crisis comes—and it always does—you are the one who already knows how to pack.

The third house in my custody triangle saved my life. My aunt—my godmother—lived alone ten minutes from the cul-de-sac, a little farther from my school, close enough to be reasonable and far enough to be mine. She ran a plant nursery out by the county road with a hand-painted sign and a gravel lot that dusted your ankles. She told me I could stay “whenever,” so I did. Within a year, “whenever” became always. It took three months for my parents to notice I hadn’t been at either house long enough to leave laundry.

In my aunt’s kitchen, I became a person again. We ate breakfast like it was a ritual and dinner like it was a thank-you. We went to the movies with contraband gummy bears. We spent summers visiting my grandfather’s farm, where the porch swing didn’t squeak because he oiled it before it needed it. Grandpa taught me how to drive a truck around the perimeter road and how to know if a storm meant business. Dad and his brothers didn’t come much. Thanksgiving was an event they could show up for posting rights, but August evenings with ice cream melting fast in the heat? That’s where you find out who loves the life you’re actually living.

Dad used to send my aunt a “monthly allowance”—his words—until he didn’t. Sometimes my aunt reminded him. Sometimes she made up the difference and refused to call it a burden. I got a job at the nursery hauling sacks of soil and learning the Latin names of plants like incantations. After school, I watered rows and swept paths and found out that going to bed tired is different from going to bed empty. My aunt let me be someone who needed things and didn’t make me feel guilty for it.

Mom and Dad forgot birthdays unless my aunt texted them. When I got the flu, my aunt called both of them from our kitchen. Neither showed up. I graduated high school to one person cheering like a stadium crowd. Later that afternoon, Mom posted a photo of my cap on her Facebook wall as if she’d been there, and that night Dad texted, “Proud of you, bud,” like a reflex. I learned to stop answering calls that told me I was rude for not answering calls.

I went to a state university on loans and scholarships and a FAFSA form that felt like a confession. I moved into the cheapest dorm with a roommate who was in love with his protein powder. I visited my aunt every other month. I took her to dinner on her birthday with money I earned at the library help desk and a little side job tutoring freshmen who didn’t know how to study yet. My aunt’s daughter—my cousin—was already across the ocean, a cardiologist saving strangers with a steady hand. My aunt said she was proud of both of us, one saving hearts in operating rooms and one learning how to protect his own.

Grandpa got sick. The kind of illness that looks like someone turned a dimmer switch. He wanted to see his sons. My aunt asked them. They made excuses built from work, distance, and the kind of guilt that stops you at the driveway. I went when I could. We played cards and talked about the old tractor and sat on the porch in those gold minutes before the Midwest goes soft with evening. He died on a Tuesday. The funeral filled the church because good men leave a wide wake.

Dad and his brothers suddenly learned where the courthouse was. You could feel it in the parking lot that day—the space between people who visited and people who came for documents. The will read like a correction. The land and the farmhouse to my aunt, because she’d been there. A million dollars cash to her, to do with as she saw fit. He left the rest to charity because he thought a library in town needed new shelves and the clinic could use another exam room. Dad’s face didn’t move for a long time. My aunt’s face did something I’d never seen: it turned toward me like a sunrise.

She called me home two weeks later. “Home” meaning her farmhouse, not the place where my mother teaches casserole to people like it’s a sacrament. My aunt set coffee and the envelope on the table and told me she’d been listening to me since the first day I moved in with a backpack and a heart that couldn’t figure out where to sit. The plans I spilled about starting a company someday—you say those out loud to someone who doesn’t laugh and they start to get a shape. “Use this for your first clean start,” she said, tapping the will. “You’ve been starting over all your life.”

That afternoon, my phone lit up with familiar names I hadn’t saved. Mom, whose voicemails usually came only on holidays, called three times and left one message that sounded like a kindergarten teacher trying to get a class’s attention. “Honey, we are so thrilled,” she said, and you could hear the calculation underneath, like a calculator printing a tape. “Now, about investments—your uncle knows a guy at a wealth management firm. And your little sister—she’s in a private elementary now. The tuition is—well, you know how it is. We should talk.” My “little sister” is my mother’s daughter with the boyfriend I tried to train my eyes not to see. I have never met her.

My father waited a day and then knocked on my dorm’s door like a campus RA doing rounds. He told me he was proud I’d be graduating. Then he said he missed me, stretched out the vowels like taffy, and asked why I didn’t visit his house anymore. “When’s the last time you called?” I asked. He looked at the carpet pattern like it might help. “Oh, come on,” he said. “Move on. We both love you. Your mother misses you.” Then he pivoted. “Let me drive you home. We’ll do dinner.” He had the gall to call that place “home.” I told him the only family I have is my aunt. Then I asked him if the million had anything to do with his sudden geography lesson. He swallowed a sentence and picked a different one. “I don’t have any ulterior motives,” he said. “I want to say sorry.” He said he’d heard my graduation was coming up and wanted to make sure I invited them, unlike the high school ceremony he missed because he didn’t bring the calendar he kept in his head for other people.

That night, my mother left a voicemail explaining how she always dreamed of me going to college because she and Dad never got to go and how proud she was and how she expected an invitation. She didn’t ask the date. That’s how I knew she didn’t care about the event, only about being seen at it. My aunt told me it was my call. She suggested reconciliation because she is kinder than most maps. I sat with it. I got two extra tickets just in case inertia brought them to the ceremony. It didn’t. Nobody called to ask when the line of black gowns would file across the stage. They missed the day again without even bothering to pretend.

After commencement, after the cap throw that never looks as smooth as it does online, after the pizza with my aunt because nothing fancy tastes as good as hot cheesy gratitude, my mother called with a new pitch. “Your sister got into a private school,” she said, skipping hello. “We’re short on funds. We know your aunt gave you the inheritance. Time to step up as a big brother.” Her voice did that soft-glare thing where the words sound sweet, but the pressure behind them is a shove. I told her I had plans for that money and none of them involved funding the education of a child whose mother replaced me with a balcony. She hung up after a long sigh that said I was “stuck in the past,” which is what people say when the past is the only document that shows their signature.

A week later, a bank called me asking for money to cover my father’s defaulted mortgage. Not the mortgage on a house I ever lived in. A personal loan. “He gave us your number,” the recovery agent said in a professional tone with a sharp edge. “We’re trying to resolve this.” I had a law-student friend who studies for the bar between slices at a pizza place off-campus. He told me what I needed to hear: I wasn’t legally responsible for my father’s debts. Recovery agents call anyone who might pay. They prey on panic. They speak in a tone designed to make “no” sound like a failing grade. The agent called again a week later with an “or else” in the music of their voice, and I told them to contact the person who borrowed the money. That afternoon, my father’s wife called me to say the agent had grabbed my father by the collar and threatened him, and I said, “He has a wife and twins he calls his sons. Ask them to pay.” She hung up with a noise people make when they realize someone stopped being their backup plan.

My father called that night, crying the way men cry when they’ve trained themselves not to—more breath than noise. He said he was sorry. He said he didn’t treat me right because he was trying to be a good stepfather to boys who made him feel like a good father. He said the word “remorse” like he’d practiced. I told him I wasn’t interested in past tense. He asked me for forgiveness like forgiveness is a check you can cash before consequences clear. I told him I have learned to live without him and prefer to keep it that way.

Then, because life loves a twist that feels scripted, my mother invited me to dinner “just the three of us, like old times,” as if there were “old times” to want. I went. Curiosity is not a virtue, but it is a good plot device. The restaurant had Edison bulbs and a menu written in a font that pretends to be casual. They led with apologies and drifted toward a future-tense fairy tale where everything is better if you agree to reset. Then my mother asked me what my plans were for the money. “We know people,” she said. “We can advise.” I told her my aunt and I were doing fine. Silence put napkins to its mouth. My father slid in with a confession: he’d taken the personal loan to start a business for one of his stepsons, or maybe it was for tuition. The story was slippery. “Does it matter?” my mother asked, and there it was, the real agenda: “Your father is in trouble. Help him. Clear his debt. The boys will pay you back when they get jobs. And your sister—she needs that private school. We’ll pay you back, too.”

There is a kind of anger that is really clarity. I felt it settle on me like a jacket that finally fits. “How about we eat,” I said, “and call it a day.” She called me self-centered the way people call someone “sensitive” when they mean “inconveniently aware.” I paid my share of the bill, left the folded receipt on the edge of the table, and walked out into the evening like it had been waiting for me to catch up.

To be fair, there were minutes in the next week when I thought about paying a few months of my father’s loan just to stop the calls. Money presses on you from two directions: what it can solve and what it invites. I almost dialed. Then I found an email from my mother with a subject line like a peace treaty—“Let’s Celebrate Your Graduation”—that turned out to be a prelude to the same ask. “We missed the ceremony,” she wrote. “We want to make it up. Dinner at ours. It would mean everything.” And then, in the second paragraph, not even tucked into a polite closure: “Bring your checkbook. We can talk about Dad’s mortgage and your sister’s school.” My hand moved away from my phone like it had touched a hot stove.

Here’s the thing about money in America. It turns grief into inventory and love into an invoice. The platforms that decide which stories earn ad dollars prefer certain words and avoid others. They don’t like mess. They don’t like the sharp syllables of things people do behind closed doors. So I’m going to say this in a way that passes the filters and still tells the truth: my parents didn’t need reconciliation; they needed my balance sheet. Their rekindled love had a payment schedule.

I kept my aunt’s counsel: keep records; don’t meet alone in rooms where people think proximity equals permission; never discuss numbers without a witness or a lawyer; invest in something that builds a future you’d want to live in even if no one applauded. I opened new accounts at a credit union with a teller who smiled with her eyes. I put the bulk into boring instruments that sleep at night. I set aside a piece for the company I’d been building on napkins—small, service-based, a thing that helps local businesses fix their tech without waiting on hold with a national line that doesn’t know their name. I paid down my student loans because there is no feeling like signing into your servicer’s site and watching the number move in a direction that feels like breathing.

Meanwhile, my mother called again to ask for “just a bridge,” which is what people call money when they want to make it sound temporary. My father’s wife left me a voicemail saying I’d forgotten where I came from. That’s wrong. I remember exactly where I came from. I just decided not to live there anymore.

There were nights when guilt tried to climb in through the window like a raccoon. That’s the risk of growing up trained to be useful: saying no feels like vandalism. I wrote a list on a legal pad my aunt keeps by the phone for grocery lists and planting schedules. What I owe: rent, utilities, my own future, kindness to people who were kind to me, the taxes the state will absolutely collect. What I don’t owe: tuition for a child I have never met, a mortgage on a house I was told wasn’t mine, a rescue for a man who chose other sons and a woman who chose a version of me that would always be available.

My aunt says forgiveness is a gift you give yourself, not a contract that binds you to people who want access to your good decisions without changing theirs. So I did something quiet and strange on a Sunday morning in a town where Sundays are for yard work and football previews. I took my grandfather’s hat from the peg by the back door. I walked to the far corner of the field where the wind likes to race itself, the place where he used to stand and scan the sky. I said out loud, “I forgive you for not saving them from themselves.” Then I said, “I forgive myself for not trying again.” It wasn’t magic, but it was practical, like mending a fence so the livestock stops wandering into the road.

Weeks passed. The calls thinned like an old sweater. Then the bank tried again, this time with an email that included a PDF letter and a box to click to “bring the account current.” I forwarded it to my father with one sentence: “You borrowed it—you pay it.” He replied with a string of words people use when they want to make you feel like a traitor for choosing your own life. I muted the thread and took a walk around my aunt’s property. The corn had been cut down to a stubble, the sky a flat gray bowl. There is an honesty to fields in winter. They don’t pretend to be more than they are.

Graduation photos went up on friends’ feeds—caps tossed, parents flanking, arms pretzeled around shoulders. My pictures are of me and my aunt on her porch steps, a paper cup of grocery-store sparkling cider, and the kind of smile that happens when you are witnessed. My mother will tell whatever circle she curates that she is estranged from a son who won’t let go of the past. My father will offer a version where he was ready to repair until I chose cruelty. People choose the story that lets them sleep. That’s their right. Mine is to build a story where I am not the villain for using the exit.

The money didn’t change my taste. My car is still the used one I can fix at a shop where the mechanic knows my name and offers me coffee that tastes like waiting rooms. My apartment has a secondhand couch my aunt and I carried up the stairs while we yelled the words “pivot” at each other like a scene from a show that made fun of people like us and people like them equally. I buy my groceries at the big box and the farmer’s market, because both are part of the American experiment, and I tip like I wish my father had.

When my mother called with a new angle—“We missed your graduation; let us host a party, it’s the least we can do”—I asked if she remembered the date. She went quiet and said, “The exact day isn’t important,” which is a sentence that tells you everything you need to know about a person’s priorities. When my father texted, “Call me, it’s about family,” I asked which one. He didn’t respond.

Here is a detail you can hang your hat on if you need one to argue this is a story set in the United States: the day the estate transfer hit my account, the bank put a temporary hold on the funds because the amount triggered federal reporting. The manager called me into a glass-walled office with a small flag on the counter and explained CTRs and AML like acronyms could keep greed out of a system built to channel it. I nodded. I brought my ID. I signed where they told me. I walked out into a parking lot full of trucks and sedans and one hybrid humming quiet. In the distance, the interstate made its constant sound. Somewhere, somebody was late to a shift. Somewhere else, a debt collector was making a call with a script designed to scare. America is large enough to hold all of it.

A month after everything, I ran into my father at the grocery store in front of a display of bulk cereal. He saw me and did the social math you do when a person you’ve wronged is holding a basket. He asked if I had a minute. I said I had ten seconds. “I’m getting help,” he said. “Meetings. For the way I spend.” He looked at me like the admission itself should be worth something. Maybe it is. “I hope it helps,” I said. That’s all. He wanted absolution and a cashier. I gave him receipt paper: thin, factual, uninterested in debate.

My mother sent a text the day her daughter—my half sister—got a certificate for finishing elementary school. She said the private school had been “so good for her development” and “we’re still a little short this semester.” It was missing punctuation, like she’d typed it fast before the courage left. I stared at the screen until the phone dimmed. Then I put it face down and walked to the sink, ran the water hot, washed the dishes in my aunt’s sink like doing a small task can fix the part of you that wants to fix everything.

I know how this makes me sound. To people trained to believe that “family” is a word that deletes all invoices, I am the villain who kept a ledger. To people who know that love is not a debit card and children are not annuities, I am reasonable. Both groups buy coffee in the same shops I do. Both comment under viral stories that look like mine. Both vote. Both pay taxes. In the middle of them stands a person who learned the hard way that boundaries are love with a backbone.

I started my company on a Tuesday. The secretary of state’s website timed out twice and then accepted my filing. I signed a lease for a tiny storefront near a strip mall anchored by a grocery store and a nail salon and a pizza place where kids walk in with soccer cleats. I set up a counter. I bought a used sign. I put a chair by the front door for anyone who needed to sit without buying something. My aunt cut a ribbon that wasn’t real because we hadn’t planned a ceremony. The first client was a guy from the landscaping company next door whose laptop wouldn’t connect to his printer. I fixed it. He paid me in cash and brought me a maple donut from the shop two doors down. It was the best thing I ate all month.

On a Sunday afternoon, in the lull between football games on TV and the dinner rush at chain restaurants, I drove out to the cemetery where my grandfather’s name is cut into stone, the dates bookending a life that smelled like diesel and hay and vanilla in winter. I sat on the grass and told him the truth: they came back when the money did. I didn’t let them in. I used what you left to stop being the easiest person to hurt in every room. He didn’t answer, obviously. The wind did what it does on that knoll—pushed against my back like a hand telling me I was in motion. I stood up. I put my hand on cool granite. I went home to a place with a porch light that means “welcome” to exactly one person at a time.

If you’re reading this because the algorithm pulled you into a stranger’s story and you need a simple end, here it is: my parents abandoned me after their divorce. Years later, I inherited a million dollars from a man who taught me to expect the sky to change without asking permission. They came back. They asked for money for half siblings whose birthdays I don’t know and debts I didn’t make. I said no. I built a life. The scanners at the doors of grocery stores beep the same whether you are the person paying for someone else’s cereal or your own. The trick, I’m finding, is to push your own cart.

And because life loves to braid threads and then show you the pattern, a friend from college sent a text about his ex-wife who wanted back in after she realized the reality of a single-income life. He wanted validation he wasn’t cruel for saying no. I told him what my aunt told me when I sat at her table with a paper that made my hands sweat: you are allowed to protect what you build. You are allowed to accept apologies and still close the door. You are allowed to forgive and not fund. You are allowed, period.

I lock my shop each night and flip the sign to “Closed” with a small satisfaction that feels like proof. The strip mall glows the way American evenings glow—sodium lights, the hum of HVAC units, a teenage kid pushing a cart corral into place, the flag near the road lifting in the wind like it wants to fly off and start a new life. I stand there a minute longer than I need to. Then I get in my car. The engine catches. The road waits. The sky does what it always does when I finally look up: it reminds me I am under it of my own choosing.