By the time I see my son standing under the white wooden cross at the edge of a Kentucky church parking lot, the wedding rings in my hand feel heavier than the entire Holt orchard.

It’s one of those small American chapels you see off rural highways—white clapboard, a steeple that tries its best to poke the clouds, gravel lot full of pickup trucks and rented sedans. Guests drift toward the doors in shades of cream and silver, the kind of palette brides in glossy magazines insist looks “timeless.” Somewhere, a country song I almost recognize drifts from a speaker near the entrance.

I park under a maple tree and sit for a moment, both hands on the steering wheel, watching strangers walk toward my son’s wedding.

I arrived five minutes early, like I always do. Five minutes early for rehearsals and piano recitals and parent–teacher meetings and dentist appointments. Five minutes early for every important moment in Logan’s life. Five minutes early today, too.

The little velvet box sits on the passenger seat, the gold rings inside clicking softly as the car settles. Logan’s request, not mine. He insisted on using his grandparents’ bands. “It’ll mean something,” he’d said over the phone weeks ago, in that distracted tone I’ve grown used to. “Having them passed down. The photographer will love it, Mom. Old gold. Old stories.”

Old stories.

I pick up the box, slide it into my palm, and step out into air that smells like rain and exhaust. The sky is overcast, the kind of washed-out gray that makes everything feel slightly damp, even when it isn’t.

I smooth my dress—simple navy, nothing that competes with bridesmaid satin—check that the clasp of my silver necklace is centered, and start toward the chapel.

I tell myself I am only here to hand over rings. That whatever happens after that is not mine to control.

I am halfway to the doors when I see him.

Logan stands just outside the entrance, stiff in a tailored charcoal suit that doesn’t quite fit his shoulders the way farm work used to. His hands twist together in front of him, knuckles pale. Behind him, through the pane of glass, I can see a blur of flowers, candles, and the flutter of pale fabric.

Next to him, Avery waits.

She is in a fitted white dress that is not her gown—not yet—but something rehearsed and deliberate. Her hair is pinned in smooth waves, makeup perfect, mouth tight. Her posture is flawless, years of Pilates and self-help podcasts about “elevated living” pressed into each vertebra.

Her eyes meet mine and don’t move.

Logan steps away from her and walks toward me quickly, too quickly. I can see the panic already blooming around his eyes, the way his jaw tightens like he’s about to deliver bad news to a stranger.

“Mom,” he says, voice low and urgent.

I stop in front of him, close enough to see the faint stubble he missed under his chin when he shaved this morning.

“Logan,” I say.

He glances back at the chapel doors, then to the box in my hand. His gaze lands there with obvious relief, as if I’m a courier sent from the past to tie up loose ends.

“I brought the rings,” I say, holding the box out. “You forgot them.”

He takes it without touching my fingers. The motion is efficient, a transaction instead of a gesture.

“Avery’s…” He stops, licks his lips, tries again. “She’s just really stressed. Today is a lot. The photographer, the planner, her parents. She asked that today be simple. Peaceful. No… surprises.”

The word hits harder than it should. Surprise. As if my presence at my only son’s wedding is an unexpected twist.

“She asked,” I repeat.

He winces.

“Mom,” he says, even softer now. “This isn’t the right time. Maybe it’s better if you… if you sit this one out. I’ll call you tomorrow. I promise. Please just don’t make this harder than it already is.”

For a second, all sound drops away. The chatter of guests, the distant hum of traffic on the state road, the faint hymn playing from inside—they all go mute, like somebody pressed pause on the world.

I look past him.

Through the open chapel door, I can see the entryway, the polished wooden pews, the arc of white flowers framing the aisle. A bridesmaid in pale champagne laughs at something, tossing her hair over one shoulder. No one notices us standing just outside like an unfinished scene.

My son, between me and the life he’s choosing.

I look back at him.

He doesn’t meet my eyes for more than a heartbeat. He stares somewhere over my shoulder, like he’s bracing for impact from a direction I’m not standing in.

I take a breath. It tastes like rain and lilies and something sour.

“I understand,” I say, though I’m not entirely sure I do. “Have a beautiful day.”

His head jerks, as if he expected a fight, tears, a scene that would confirm whatever Avery has told him I am.

I give him nothing.

I turn and walk back across the gravel, my shoes crunching with each step. My spine feels too straight, my shoulders too square, as if someone else is wearing my body.

I don’t cry.

Not in the parking lot, not in the car. Not on the winding road back through the rolling fields of central Kentucky, past old barns and new subdivisions, past signs for bourbon distilleries and mega-churches.

The sky is still overcast. The orchard trees on our land lean in the wind like they always do in late spring, branches brushing the fence line, blossoms clinging stubbornly to damp air.

The Holt estate has stood on this land for four generations. It’s not a grand Southern plantation with columns and history stained into the walls. We are not that story. We are rows of apple and pear trees on forty acres off a county road, an unpretentious farmhouse with peeling white paint and a porch that sags in the middle. We sell fruit at the local farmers market. We host a fall festival for the school. Our biggest claim to fame is a feature once in a regional magazine under the title “Hidden Kentucky Orchards You Need to Visit Before Summer Ends.”

I pull into the gravel drive, the house coming into view over the slight rise. The porch light is still on, even in daylight—a habit I never broke after my husband died.

At home, I unlock the door, step inside, and hang my coat on the same hook I’ve used for thirty years. The house smells like lemon oil and old books and the faint sweetness of yesterday’s baked apples.

The floorboards do not care what I wore to my son’s almost-wedding. The walls do not ask where I’ve been.

I slip off my shoes, walk into the kitchen, and put the kettle on.

I make tea the way my father taught me when I was ten and grieving the loss of my favorite tree to a storm. Boil the water, let it sit a moment, pour over the leaves, wait. Some things can’t be rushed. Not trees. Not grief.

I set one cup on the table, sit down, and wrap my hands around the warm ceramic.

I don’t call anyone. I don’t tell the neighbors or my sister in Ohio or the women from church. I don’t post anything online. No one knows I was turned away like an unwanted guest at my own son’s wedding.

I don’t need to say it out loud. My silence rattles louder than any words.

The next morning, just after nine, the landline rings.

Most people don’t use them anymore, but here in rural Kentucky, cell service dips like a roller coaster, and the old brass-edged beige phone on my wall has never once dropped a call.

I let it ring once. Twice. On the third, I inhale and pick up.

“Holt residence,” I say automatically.

“Mom.”

Logan’s voice. Cautious, but lighter than yesterday, as if the vows and the photos have already made things easier for him.

“Yes,” I say.

“Hey,” he says. “So, listen… The photographer wants to do some portraits this afternoon. Me and Avery were thinking the orchard would be perfect. You know, the light, the trees. It would mean a lot.”

My eyes flick to the old key ring beside my mug, the small brass tag worn smooth from decades of turning locks. My father’s handwriting still faint on the metal: HOLT HOUSE.

“You want the orchard,” I say.

“Just for the pictures,” he says quickly. “Avery loves the wildflower roses near the fence line, and we figured we could grab a few inside the house, too. Just a few shots. It’d be quick. The place photographs beautifully.”

The place.

Not home. Not the house I grew up in. Not the land his grandfather bled for. The place.

I stand, carrying the phone with me to the front window. The orchard stretches out beyond the yard, rows and rows of trees in soft pink and white bloom. From this distance, you can’t tell anything happened yesterday. Petals don’t curl in shame. Trees don’t ask who walks beneath them.

“Ask your wife,” I say, my voice very calm. “If she wants to step foot on this land, she can call me herself.”

Silence on the line. Not long. Just long enough to feel like a choice.

“All right,” he says finally. “We just thought—”

“I heard what you thought,” I say.

He swallows; I can hear the click of it even over the line.

“Okay,” he says. “I’ll let her know.”

He hangs up first.

I put the phone back in its cradle, sit down, and stare at the cold tea in my cup. I don’t reheat it. Some things aren’t worth reviving.

Outside, the wind picks up just enough to scatter the first pale blossoms across the porch, a quiet drift of white like confetti from a celebration I wasn’t invited to.

That night, I cannot sleep. My body is tired, but my mind walks loops around the same questions until the ceiling seems to press down.

Around midnight, I get up and move carefully through the darkened house, the way I did when Logan was a baby and I walked the hallways to lull him back to sleep.

The old study door stands closed at the end of the back hall. It used to be my father’s sanctuary, then my husband’s. After he died, I left it mostly untouched, a little shrine of papers and maps and jars of pens that no longer write.

I pass it by and instead open the door to the guest room at the far end—the room that used to be Logan’s before he left for college, then for Avery, then for a city job. The bed is made, top sheet tight, throw pillow aligned. It smells faintly of dust and laundry detergent.

For a moment, I can see him again, fifteen years old, long limbs spilling off the mattress, the window cracked even in winter because he liked the cold air. He used to tape up photos of tractors and guitars and some college football team he had no intention of playing for but liked to dream about.

I close the door gently and go back to the kitchen.

My laptop sits on the table, lid closed, charger light glinting in the dark like a patient little star.

I don’t check social media often. I have an account because a friend at church insisted. “You’ll see your nieces,” she’d said. “You’ll see what the kids are doing.”

Most of the time it feels like standing outside other people’s windows.

Tonight, curiosity pulls me.

I open the laptop, type in my password, and click on the little blue icon. My profile loads slowly, the rural internet doing its best. I click on Logan’s name.

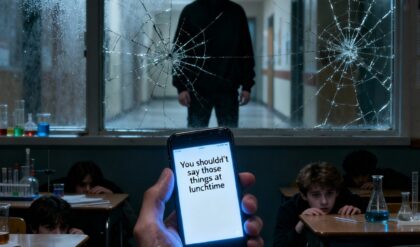

The first photo that appears is filtered golden, taken in the orchard near the fence line. Avery stands in white lace, her veil catching the light, Logan behind her, his arms around her waist, the sun flaring through the trees like a blessing.

I recognize the trees. Row Six, where my father planted the first grafted pears the year I turned twelve.

The caption under the photo reads:

Perfect start. Perfect place. Perfect family. No disruptions.

My chest tightens around those last two words.

No disruptions.

There is no mention of me. No trace of the rings I carried. No hint of the conversation in the church parking lot. The land beneath their feet is acknowledged only as an aesthetic, a background filter, a brand.

The house, the history, my hands—gone like I was never there.

I close the laptop more softly than I want to. Breaking things seldom makes you feel better for longer than a heartbeat.

In the quiet, I reach up and touch the slim chain around my neck. I’ve worn it every day since my father died, the small brass key resting against my collarbone. Sometimes I forget it’s there until I need to lock something behind me.

Tonight, I take it off. The absence feels strange, like taking off a wedding ring after decades.

I walk down the hall to the front door and look at the hook where I usually hang my keys. The ring is there, the one with house keys and shed keys and a tiny metal tag with my father’s faded script.

I take that ring down and clip it onto the chain instead, then fasten the clasp behind my neck. The weight is familiar and new all at once.

In the morning, I hear the sound of tires on gravel.

Two sets of footsteps approach the front porch, the cadence of people who think they belong.

They don’t knock. They step onto the porch like it’s theirs, like it always has been. I open the door before they reach to ring the bell.

“Morning,” Logan says, with a brightness I don’t buy. His eyes skitter away from mine.

Avery stands beside him, in a well-pressed blouse and tailored pants, hair sleek, makeup subtle. She holds a manila folder in front of her like an offering or a shield. Her lips curve into the same tight line she uses in photographs when she wants to look approachable.

“We thought we’d come by with something exciting,” she says.

I step back.

“Come in,” I say. “The kitchen’s this way. I assume you remember it.”

They sit at the table like guests, not family. Logan pulls out a chair and brushes dust off his shoes before placing them carefully beneath him, like he’s afraid to scuff the floor. Avery sits upright, crossing her ankles.

I stay standing.

“So,” Avery begins, flipping open the folder. Her fingernails are pale pink and perfectly shaped. “We’ve been thinking.”

I almost smile.

“Have you,” I say.

“The orchard,” she says. “The house. This whole place has incredible potential.”

Logan leans forward, eager, like a man presenting a pitch deck to investors.

“With the wedding,” he says, “people kept asking if we’d rent it out. For photos, receptions, even weekend retreats. Everyone said it looked like one of those destination venues on Instagram.”

Avery’s eyes light up with the memory of compliments.

“It could be the perfect venue,” she says. “Rustic, elegant, marketable. With a little investment, we could modernize the barn, add outdoor lighting, redo the guest wing. Keep the charm, but elevate it.”

I wait. I’ve learned that if you don’t rush to fill a silence, other people will tell you exactly who they are.

“Of course,” she adds quickly, “it wouldn’t be just for others. We’d stay here too. Oversee things, manage bookings. Make sure everything runs smoothly. It would be good for all of us.”

“And me?” I ask.

They hesitate. The first crack in the polished plan.

Avery clears her throat.

“Well,” she says, “obviously you’d be welcome. But maybe this is an opportunity to… transition. You’ve said yourself the winters are getting harder on you. The maintenance. The isolation.”

I haven’t said that. I’ve said my knees ache on cold mornings and the pipes need looking at. I’ve said it the way anyone who works land says it: as an observation, not a surrender.

Logan reaches across the table as if to take my hand. I don’t move mine toward his.

“Where exactly would I go?” I ask.

They exchange a glance. Not surprised. Rehearsed.

“There are lovely retirement cottages near Ashgrove,” Avery says. “We looked into a few. You’d have your own space. Community, activities, medical support on-site. No pressure. Just… quality of life.”

I look past them to the window.

The row of pear trees nearest the yard needs pruning. The hydrangeas by the porch are late to bloom this year. The barn roof has a patch that should be checked before fall storms.

“You’ve been busy,” I say.

Avery smiles again, falsely certain she’ll be able to talk me into seeing this as a gift, not an eviction.

“Logan just wants to make sure you’re taken care of,” she says. “And the estate stays in the family but… evolves.”

Logan doesn’t meet my eyes.

“Let me think about it,” I say.

Relief rushes over his face like sunlight. They both stand quickly, leaving the folder on the table.

“HOLT ESTATE DEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL,” it reads across the top in bold, confident letters.

When their car disappears down the drive, I don’t open it.

Instead, I walk down the back hallway and open the door to my father’s old study.

The room smells faintly of old paper and dust, a ghost of pipe tobacco, though no one has smoked in here in decades. Sunlight filters through the sheer curtains, dust motes suspended like very small planets.

I haven’t been in here properly in months. Maybe longer. Grief has a way of turning familiar rooms into heavy places.

But the moment I step inside, I know something is wrong.

The desk chair is angled slightly outward. My husband always pushed it in when he left the room, a habit picked up from my father. The cabinet door under the window is ajar. And the bottom drawer of the gray metal filing cabinet—the one my father always kept firmly shut with a key—is pulled out just enough to notice.

Someone has been searching.

I cross the room and crouch in front of the drawer, sliding it open the rest of the way. Folders lean at uneven angles, the normally meticulous stacks disrupted like a bookcase after a child’s visit.

The survey maps of the orchard usually sit in a precise order, labeled by decade, the edges worn by years of handling. Now the top map is missing. The one that shows the updated boundary lines after my father purchased the north field from old Mr. Jennings twenty-five years ago.

I flip through the remaining maps. ’72, ’84, ’96. No 2001.

In the cabinet under the window, an old three-ring binder lies open, pages fanned. Contracts for tractor repairs, tax assessments, equipment receipts. Nothing dramatic on its own. But someone has been looking.

Not reminiscing. Not grieving.

Looking.

My father was many things—stubborn, brilliant, infuriating—but never careless. He believed in backup plans and secret compartments more than he believed in most people.

I glance at the bookshelf along the far wall. The bottom shelf sags slightly under the weight of old ledgers. When I was a girl, he once called me into the room, pulled down a worn account book, and showed me how to balance columns by hand.

“Numbers don’t lie,” he’d said, tapping the page. “People do. The more you understand this,” he’d tapped the ledger, then the wood floor, then his own chest, “the less they can take from you.”

It takes me a moment to spot it—the faint seam at the base of the shelf, nearly invisible in shadow.

I slide my hand along the underside until my fingers catch on a small carved edge. I press and feel a narrow piece of wood give slightly, then lift away.

Inside the hidden space is a paper envelope, thin and brittle with age, sealed. My father’s handwriting covers the front in firm, precise strokes.

For Marin, only if needed.

My throat tightens.

I sit in my husband’s old chair and open the envelope carefully, the paper tearing soft and dry.

Inside, there is a single-page letter and a notarized clause, both dated.

The clause is an amendment my father filed years ago, reinforcing that I alone hold administrative control over the estate until my death—or until I choose, in writing, to transfer that authority. No shared control. No automatic handover to my children. No third-party management without my explicit consent.

The date at the bottom startles me.

He signed it the summer after Logan’s first year of college. Before Avery. Before hashtags and proposals and development folders.

Before any of this.

He saw our future fractures further than I did.

The letter is shorter.

Marin,

If you are reading this, it means someone is trying to talk you out of what you have already earned a hundred times over.

You owe no surrender to those who did not plant, prune, harvest, or repair when storms came through.

Love them, if you choose. But do not hand them the keys to what they do not understand or respect.

Protect the land.

Protect yourself.

—Dad

Tears blur the ink for a second. I blink them away; he would hate to think his words caused smudges.

I fold the documents back into the envelope and leave the study, closing the door behind me.

In my bedroom, I reach up to the closet’s top shelf and bring down the metal box that holds our family’s most important papers—birth certificates, my marriage license, the original deed to the property, the will my husband and I drafted twenty years ago.

I add my father’s envelope to the stack and lock the box with a small brass key I slide back onto my chain.

Outside, the orchard sways in the wind like it always has, but the house feels different. Not threatened. Awake.

Early the next morning, as sunlight touches the tops of the trees, the phone rings again. It’s not Logan. It’s Henry.

Henry Carter has been our lawyer for as long as I can remember. He did our closing when we refinanced the barn loan. He drafted my parents’ will. He wrote a letter once that scared the county into fixing the culvert by our drive before it collapsed.

He retired two years ago, said he was done arguing with people in suits and wanted to spend his days in his vegetable garden out past town, watching tomatoes ripen instead of clients panic.

“Marin,” he says. “You got a minute?”

“For you, always,” I say.

“I was going through some old files,” he says. “You know I’m cleaning out the office. Found something with your father’s name on it. Thought you might want to see it. In person.”

“Is it bad?” I ask.

“Depends who you are,” he says mildly. “I’d say it’s useful.”

I drive into town that afternoon. The law office sits on the main street near the courthouse, wedged between a bakery and a secondhand shop. American flags flutter from lampposts up and down the block. A pickup with a faded U.S. Army bumper sticker is parked in front of the post office.

Inside, the waiting area smells like coffee and old carpet. The receptionist waves me in with a familiarity that comes from decades of property tax disputes and neighbor boundary agreements.

Henry’s office is smaller than I remember. Or maybe I am larger now, heavier with years and decisions.

The folder is already waiting on his desk.

“Recognize that handwriting?” he asks.

My father’s name is on the front. The envelope inside looks like a twin to the one I found in the study, only older.

“He left this with me the same day he filed that amendment with the county clerk,” Henry says. “Said it should only reach you if certain conditions were met.”

“What conditions?” I ask.

“Lawyers with glossy brochures,” he says dryly. “Noise about ‘unlocking latent value’ and ‘optimizing the estate.’ You get the idea.”

I do.

I open the envelope. The paper inside is thick, the ink faded but legible.

It’s another letter.

Marin,

If they have found Henry, it means they are not coming to you directly with respect. They are coming with paperwork and pressure.

Remember this:

Land is not a brand. It is not a backdrop. It is not “content.”

It is work, memory, sweat, and promise, all layered together.

Whoever inherits this place must love it more than what it can provide them.

If they love the income more than the trees, do not give it to them.

You do not owe any child a legacy they would only strip for parts.

Choose the land’s keeper, not its owner.

—Dad

P.S. If it’s Logan, look at his hands. They will tell you more truth than his words.

I swallow hard and slide the letter back into the envelope with careful fingers.

“You know what to do,” Henry says quietly.

I nod.

That afternoon, I update my own will.

We list the property by name, acreage, and lot description. We clarify that administrative authority rests solely with me until my death. We add language my father would approve of and some he might not—explicit conditions that inheritance requires demonstrated care for the land over a period of years, not just blood ties.

No transfer without my consent. No guardianship over me or the estate. No sale in the event of my illness unless I sign paperwork on a day when my doctor confirms I understand every line. I ask for copies of my last two checkups and tuck them into the file.

Control is not about dominance. It is about not being moved without your feet.

That night, I sit on the porch with a cup of tea and watch the wind move through the trees like a tide. The orchard is still mine, not just because of ink or signatures, but because for the first time I am willing to hold it without apology.

The next day, just before noon, tires crunch on the drive again.

One car this time. One door slams.

Avery.

She walks up the path with a clipboard tucked against her chest like a credential. Her heels sink slightly into the gravel, but she doesn’t slow.

I step onto the porch and wait.

“I wanted to speak without distractions,” she says, brisk and purposeful. No greeting. “This is moving forward, Marin. With or without your cooperation.”

I tilt my head.

“Is it,” I say.

She taps the clipboard.

“We’ve already spoken to a contractor,” she says. “The venue conversion will start with the barn. We’ll need to reinforce the beams, add climate control, redo the floor. Then we’d expand the driveway, replace the fencing, reroute irrigation. The house would be next. Cosmetic updates at first, then perhaps an addition.”

She speaks like someone reciting a vision board.

“Logan and I will live on site, at least part-time,” she continues. “We’ll be the face of the brand. You can choose how involved you want to be. Stay here or relocate comfortably. We found another community near Lakeview with excellent reviews. All expenses covered.”

She softens her voice, like a commercial for senior living.

“We’re offering you freedom,” she says. “You’ve carried this alone long enough.”

I let her words hang between us. Birds chirp in the oak above. Somewhere down the road, a truck shifts gears.

“I know this place means a lot to you,” she adds. “But sometimes we have to let go of what was to make room for what could be. You holding on isn’t helping anyone. The land could finally reach its full potential.”

I think of my father’s letter. The line about loving income more than trees.

“You’re not the only one with a vision anymore,” she finishes.

I step forward, not rushed, not angry. Just steady.

I reach for the gate and open it wide.

Avery blinks, thrown.

“I think we’re done here,” I say.

“Marin—”

I close the gate behind her with a quiet, firm click. There is no raised voice, no insult. That would give her something to push against.

All I give her is the truth of where she stands and where she no longer belongs.

She lingers on the other side for a moment, lips parted, as if searching for one more persuasive phrase. Then she turns and walks back to her car.

From the porch, I watch the vehicle disappear down the dirt road, dust rising behind it like smoke after a fire already burned out.

The orchard seems to exhale.

That night, I sleep with the windows open, the scent of blossoms drifting in, crickets singing like nothing has shifted and everything has.

Days pass.

I prune branches. I mend a fence. I walk the rows at dawn and dusk, the same way my father did, the same way his father did, boots pressing into earth that recognizes the tread.

No calls from Logan. No more cars up the drive. No thick envelopes from new lawyers. Just the everyday sounds of rural America—distant tractors, dogs barking, a siren once in a while on the highway that runs toward Lexington.

Then, nearly four weeks after I closed the gate on Avery, a blue sedan pulls into the driveway at dusk.

Logan.

He steps out slowly, like he isn’t sure how gravity works anymore.

No suit this time. Just jeans and a wrinkled shirt. No clipboard. No portfolio. No ring on his left hand.

His hair is uncombed, beard shadowed in a way that says “not sleeping” more than “trying a new look.” There’s a hollow around his eyes I recognize from nights he cried as a child and didn’t want anyone to hear.

He stands next to the car and looks at the house for a long time, hands in his pockets, shoulders slumped. He looks smaller now, somehow, not in height but in certainty.

I open the door and stand in the frame.

He hesitates, then walks toward the porch. He stops at the bottom step like it might require a password.

“Come in,” I say.

He follows me into the kitchen, pausing at the threshold like he’s entering a museum instead of the room he grew up in.

I pull out a chair and sit. He takes the one across from me slowly, cautiously, like he’s not sure if he’s allowed.

“She left,” he says at last.

I wait. There are a hundred ways that sentence could end. Only one seems likely.

“She said I wasn’t ambitious anymore,” he continues, staring at a knot in the table wood. “Said I let something small ruin everything we were building. That I was choosing ‘sentiment over success.’”

He laughs once, a short, bitter sound.

“She meant you,” he says. “And this place.”

I say nothing. Sometimes silence is more honest than any platitude.

He flexes his hands on the table, knuckles whitening.

“I pushed you away,” he says. “Every time she rolled her eyes at something you said, I laughed along. I let her talk for me. Decide for me. I told myself it was easier. That she knew better. That maybe this place really did need change and I didn’t know how to make it happen.”

He finally looks up, meets my eyes fully for the first time in a long while.

“But it didn’t,” he says quietly. “Need that kind of change. I did. I just needed to grow up.”

I stand and move to the counter, filling the kettle and setting it on the stove. The movements are muscle memory now, my own ritual for moments that threaten to tip into something too big.

I set two mugs on the table. Coffee, no sugar for him, just like when he was nineteen and studying for exams at our kitchen table, caffeine replacing sleep.

He takes the mug with both hands, like he’s not sure he deserves it.

We don’t talk much after that. Words are fragile things. Overuse can snap them.

He sits with his back to the window, watching the orchard fade into dusk, the trees turning to dark silhouettes against a pink and blue sky. I watch him, the line of his jaw so like his grandfather’s, the stubborn tilt of his head so like mine.

Some people don’t need to be forgiven out loud. They just need a door left unbolted when they decide to walk back through it.

The next morning, before he says anything else, he appears at the back door in an old t-shirt and work gloves.

I slip on my boots and step out onto the porch.

He doesn’t ask what to do. He just falls into step beside me as I walk toward the south row, the one with the older trees that need careful hands.

He doesn’t move back into the house. Not right away. Instead, he cleans out the old tool shed near the barn. It takes him two days to clear the cobwebs, scrub the concrete floor, patch a draft in the wall, and drag in a narrow bed and small dresser from the attic.

“It feels honest starting small,” he says, not looking at me.

Each morning after that, I find him already out in the field at first light. Hauling branches, checking the drip lines, trimming back overgrowth without needing a list.

He doesn’t ask for praise, and I don’t give it. But I brew a little extra coffee and leave a thermos on the porch rail where he can see it.

Weeks stretch into a new rhythm.

He asks about the root systems in Row Three, the grafting methods in the north field, the signs of early blight. I answer when needed. Other times, I let the land itself instruct him. Trees are impatient with arrogance but patient with effort.

Sometimes, we talk about nothing at all. The weather. The neighbor’s new dog that keeps slipping the fence. The local high school football team that hasn’t won a home game all season.

Sometimes, we say almost too much and then pull back.

One evening after we’ve finished stacking firewood along the barn wall, we sit under the old elm near the house. The sun spills gold over the orchard, catching on white blossoms like small lanterns.

He clears his throat.

“Will the keys ever be mine?” he asks.

I don’t answer right away. I reach up instinctively, fingers finding the thin chain around my neck, the small brass key resting where it always does.

The metal is cool against my skin, warmed only by my own body.

“When you’re ready to carry what they mean,” I say finally. “Not just own what they unlock.”

He nods. There’s no argument, no impatient eye-roll, no letting someone else speak for him. Just acceptance.

Some doors don’t open with metal alone. They open with calloused hands and repeated choices.

The next morning, he meets me at the southern row with gloves already on. I hand him the pruners without a word.

He doesn’t need instructions anymore.

We walk the rows together the same way my father once walked them with me—stopping to touch bark, check leaves, listen to the quiet.

The orchard, like any piece of land in this country, has seen wars and recessions, droughts and floods, divorces and births. Its roots run deeper than any one marriage, any one argument, any one proposal presentation in a kitchen.

That night, when I undress, I slip the chain off my neck and set it on the bedside table.

For a moment, I just hold the key in my palm, fingers closing around it.

It feels lighter than it used to.

Not because it matters less. Because I’m no longer pretending I must hold it alone forever.

In the dark, with the window cracked open and the sounds of Kentucky night drifting in—crickets, a distant train, the low murmur of wind in the branches—I understand something my father tried to tell me in a hundred quiet ways:

Love is not surrender.

Care is not the same as control.

And sometimes, the bravest thing you can do for a piece of land, or a child, or yourself is refuse to hand the keys to anyone who sees it only as “potential.”

America loves stories about inheritance and big dramatic readings of wills in oak-paneled rooms. But most real legacies in this country are decided in kitchens and orchards and small-town lawyer offices. They are decided by who shows up at dawn with work gloves. By who sees land as more than a backdrop for photos. By who understands that roots are not a trap, but an anchor.

I used to think my life would end with my son taking my place and his wife smiling beside him, everyone neat and tidy as a catalog picture. But pictures lie. Sometimes the bride doesn’t want the woman who kept the lights on in the background. Sometimes the son forgets which side of the camera he’s meant to stand on.

But the land? The land remembers.

It remembers who pruned in winter when the branches cut like ice. Who hauled hoses in July heat. Who slept with the window open, listening for the first patter of a hailstorm.

It remembers my father’s boots. My husband’s laugh. My son’s first steps between the rows. It remembers me.

And now, as spring leans quietly toward summer, it will remember this, too:

The day I chose myself and the orchard over a development plan with glossy renderings.

The day I closed the gate on someone who tried to define “family” as “whoever can monetize you the most.”

The day my son walked back up the drive with empty hands and slowly, stubbornly, started earning the right to hold the key his grandfather left for him.

No photographers capture this part. No filtered caption reads “Perfect place, perfect family, no disruptions.”

But if you stood on the county road that runs past the Holt place at sunset, you might see two figures walking between the trees—one older, one younger. You might see the way they move in quiet rhythm, stopping here and there to bend, to touch, to study, to learn.

You might not know which of them holds the key.

And that, finally, is the point.