On the morning the sheriff’s cruiser rolled into Mango Park, the Florida sun was already turning every “VOTE MOREHEAD” yard sign into a flashing yellow warning.

Blue lights strobed down Mango Palm Drive, bouncing off manicured lawns and identical mailboxes with little American flags stuck in their sides. The HOA office—really just a converted model home at the entrance of the Jacksonville subdivision—sat prim and square under a giant vinyl banner:

VOTE MOREHEAD

KEEPING MANGO PARK CLEAN, SAFE, AND ORDERLY

By noon, that banner would be hanging sideways, caught on a nail, while the woman whose name was printed in all caps on it walked out in handcuffs.

But at nine a.m., Diane Morehead still thought she ran the world.

She stepped out of her silver SUV like she was exiting a limousine on Election Night. The Florida heat hit her full in the face, but she didn’t sweat. Diane was the kind of woman who seemed laminated—helmet of blond hair, bright coral lipstick, crisp white blouse tucked into navy capris. A polished, HOA-perfect hurricane.

She paused to straighten one of her signs that had tilted in the breeze, brushing imaginary dust from the plastic.

“Keeping Mango Park clean, safe, and orderly,” she read out loud, smiling at her own slogan. “Sounds more like I’m running for mayor of Duval County than president of a condo association.”

She liked the way it sounded. President Morehead. Enforcer. The woman who made sure everybody’s grass was the same length and nobody’s inflatable flamingo stayed up past Labor Day.

Across the street, behind a curtain patterned with seashells, Velma Richardson watched Diane fix her own campaign sign and muttered, “You’ve kept it orderly, all right. Especially the money going straight into your bank account.”

Velma had lived in Mango Park longer than the palm trees.

She moved in twenty-two years ago, back when the development was nothing but fresh stucco and promo flyers promising “Resort-Style Living 15 Minutes from the Jacksonville Beaches.” She’d raised two kids in her narrow townhouse, seen three hurricanes pass close enough to peel the paint off her front door, and watched more HOA presidents come and go than she could count.

Diane was the worst.

At first, the community had loved her “energy.” She’d swept into office with color-coded binders and a Facebook group called Mango Park Neighborhood Watch & Wellness. People liked having someone who knew every bylaw and could recite Section 7 Subsection C about trash cans from memory.

Then the notices started.

Yellow slips taped to garage doors for trash bins one inch out of alignment. Email blasts about “aggressive behavior” after somebody let their labrador off-leash for thirty seconds. A three-page letter telling Velma’s neighbor her holiday wreath was “not consistent with the seasonal color palette” and needed to be removed.

“Who even enforces this stuff?” new residents would complain.

And someone would answer, with a mix of fear and disbelief, “Diane. She calls herself the HOA enforcer.”

It would have stayed irritating but harmless if Diane had limited herself to policing pet waste and Christmas lights.

But Velma had been a school administrator for thirty-five years. Numbers were the one thing nobody could sweet-talk her around.

The first time she really looked at the HOA financial report, she was sitting at her kitchen table with a mug of coffee, the latest newsletter spread out next to a stack of coupons.

“Maintenance Fund Reallocation,” the bold heading said.

Due to increasing costs, annual dues will rise by $40 per household, effective immediately. Funds will support pool maintenance, landscaping upgrades, and community safety.

Velma frowned. The pool had been closed for tile repairs for weeks. The hedges along Mango Palm Drive still looked like they’d been trimmed by guesswork. Security cameras at the front gate had been “coming soon” since last year.

Where, exactly, was the money going?

She turned the page. At the bottom, in smaller print, were three new line items:

PB&J CONSULTING – $2,800

SUNRISE LANDSCAPING – $1,500

COMMUNITY WELLNESS OUTREACH – $1,200

She’d never heard of any of those vendors.

Velma picked up her reading glasses and squinted. Next to each vendor was a tiny note: EMERGENCY SERVICES. APPROVED BY PRESIDENT.

“Emergency my foot,” she said.

Most people would have shrugged, sighed, and complained about it at the mailbox. Velma walked to her bedroom, opened the drawer of her filing cabinet, and pulled out everything she’d kept from the past two years of HOA mail.

She spread the papers across her dining table and went to work.

By the time the afternoon sun turned the mango-colored walls golden, Velma had circled half a dozen suspicious entries. PB&J Consulting appeared three times with different descriptions—“community engagement,” “policy review,” “strategic planning.” Sunrise Landscaping had never, as far as Velma could remember, set foot in Mango Park. And “Community Wellness Outreach” seemed to be code for whatever personal errand required checks in odd amounts.

She took a breath, sat back, and stared at the pattern.

“Somebody thinks we’re all asleep,” she muttered. “They picked the wrong zip code.”

The next step was as careful as it was inevitable.

Velma lived alone now, but she wasn’t lonely. She had the Mango Park retirees, her church friends, and a lifetime of knowing which doors to knock on when something smelled off.

First, she checked the vendor names online. No website for PB&J Consulting. No LinkedIn. No state business registration. Sunrise Landscaping? Sure, there were three companies in Florida with similar names—but none with the address listed on the HOA report.

She called the number printed on the invoice. Disconnected.

Her spine prickled.

At the Duval County Clerk’s website, she dug into property records and corporate filings like they were old test scores. One name kept reappearing in the fine print, tied to a small local bank a few miles away.

D. MOREHEAD.

“I knew it,” Velma said, heart thudding. “You really thought nobody would follow the money.”

She didn’t call Diane.

She made an appointment downtown.

The Jacksonville Police Department’s community precinct on Atlantic Boulevard was a functional box of a building, all concrete, faded blue paint, and American flags. The waiting area chairs squeaked when you sat in them and the coffee tasted like someone had brewed it in 2003 and just kept topping off the pot.

“Mrs. Richardson?” a voice called.

Velma stood. The man walking toward her wore a tan shirt with silver bars on the collar and a name tag that read SANCHEZ. He was in his late forties, with steady eyes and the kind of face that had heard every excuse.

“I appreciate you seeing me on such short notice, Lieutenant,” Velma said, businesslike but polite. “I’m here about Diane Morehead.”

“The HOA president?” His mouth twitched. “Let me guess. Another parking dispute.”

“No.” Velma set her leather tote on the table between them and pulled out a manila folder so thick it looked like a novel. “Much worse. I’m afraid she is guilty of fraud.”

His eyebrow lifted. The word sat in the air, heavy.

“Are these the official HOA records?” he asked.

“Copies of the originals,” she said. “Payment authorizations, budget allocations, vendor details. I highlighted the ones that didn’t add up. Look closer. Some of those vendors don’t exist.”

He flipped through the pages. The fluorescent lights hummed overhead, the only sound besides the soft whisper of paper.

“How sure are you about this?” he asked eventually.

Velma crossed her arms. “I’ve been living in Mango Park for twenty-two years, Lieutenant. I know this community. I know people. And I know when numbers are lying.”

He found the PB&J Consulting line and frowned. “$2,800, approved by president only…”

“Now check this,” Velma said, producing a printed screenshot of the bank’s online routing info. “That check, and at least two others like it, end up in an account with Diane’s name on it. There’s no board approval. No contract. Nothing.”

Sanchez blew out a breath, low. “You really did your homework.”

“She thinks the HOA is her personal kingdom,” Velma said. “That she can raise dues, write herself checks, and the rest of us will just keep paying and letting her tape violations to our doors.”

“Misappropriation of funds is a serious offense,” Sanchez said, sitting up straighter. “I need to verify all of this, but if what you’re saying is true, Ms. Morehead could be facing real charges.”

Velma nodded once. “Then please verify it. Because she loves enforcing rules on everybody else. I’d like to see how she feels when the law is enforced on her.”

He walked her to the door. “Thank you, Mrs. Richardson. We’ll look into this.”

Velma shook his hand. “I appreciate your time, Lieutenant. And for the record?” She tipped her chin. “I still believe in HOA rules. I just don’t believe they should be for sale.”

When she left, Sanchez stood in the doorway for a moment, watching her cross the parking lot under the Florida sun. Then he turned to the officer at the desk.

“Hey, Haron,” he called. “Got a minute to check something for me?”

“Sure, Lieutenant,” Officer Haron said. “What’s up?”

“Name’s Diane Morehead,” Sanchez said. “Mango Park Condo Association. HOA president. I think we may have just gotten a very solid tip.”

That afternoon, while Diane was taping yet another warning notice to a mailbox—NO UNAUTHORIZED YARD DECOR AFTER 10 P.M.—two detectives sat in front of a computer screen downtown, pulling bank records through a subpoena and watching numbers line up exactly the way Velma said they would.

Two thousand eight hundred dollars to PB&J Consulting, deposited into a personal checking account belonging to one DIANE E. MOREHEAD.

Fifteen hundred dollars to Sunrise Landscaping, also landing in that same account.

A series of smaller checks marked “reimbursement for supplies,” “community outreach expenses,” “meeting refreshments,” all winding up in the same place.

On paper, the story wrote itself.

In Mango Park, though, the story started with paper of another kind.

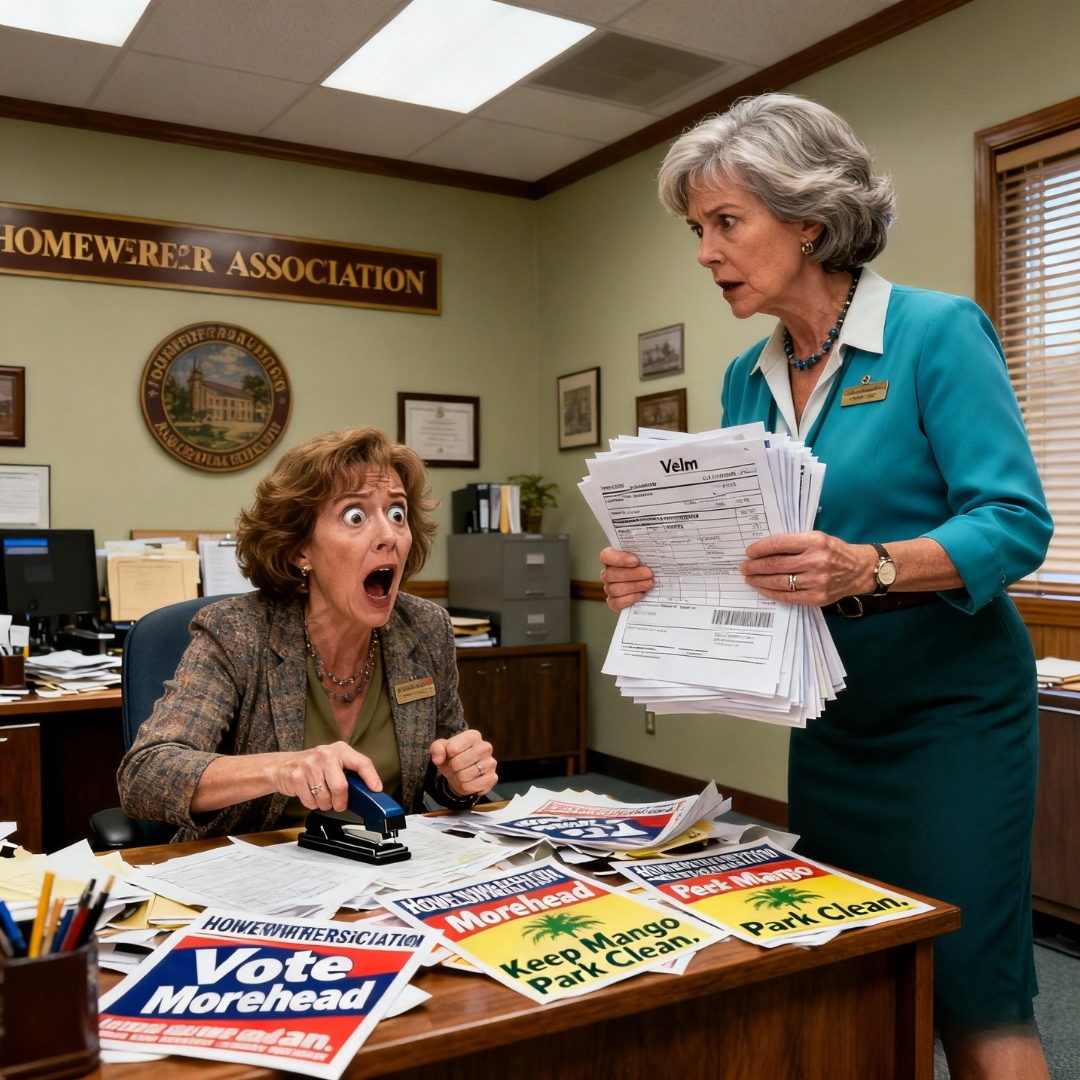

Three days after Velma’s visit to the station, she walked into the HOA office at ten on the dot. She’d dressed for battle—pearl earrings, pressed slacks, her old principal’s blazer that caused teenagers to stop chewing gum on sight.

Diane sat behind the front desk, hunched over a stack of flyers. She looked up, lips already curling.

“Well, if it isn’t Ms. Bake Sale herself,” she said. “What’s the emergency, Velma? Decide to turn in your yard flamingos voluntarily?”

Velma didn’t sit. She opened her tote, set a binder on the desk between them, and flipped it open to the first flagged page.

“I came to talk about this,” she said.

Diane rolled her eyes so dramatically it was a wonder they stayed in her head. “Another one of your ridiculous petitions? You think you can win over Mango Park with your Sunday smiles and cookies? I’ve kept this place running for five years. You have no idea how much work that is.”

“These are financial records,” Velma said calmly. “The past two quarters. Vendor invoices. Expense reports. Bank statements.”

Diane reached over, glanced down, then shrugged. “Everything looks fine to me.”

“You authorized a charge for $2,800 to PB&J Consulting,” Velma said. “No one on the board ever heard of them. And there’s a $1,500 check to a landscaping company that doesn’t even have a website or a business license.”

“Those were emergency services,” Diane snapped. “We had a leaking sprinkler main. I made an executive decision.”

“We are a homeowners association, Diane,” Velma said. “Not Homeland Security. There is no such thing as an ‘executive decision’ that lets you bypass the board, invent vendors, and deposit checks into your own account.”

She slid a printed bank printout across the desk. “These statements show the checks went to an account under your name. You’re not slick. You’re just sloppy.”

Diane’s face flushed a sharp, blotchy pink.

“Listen here,” she said, leaning forward. “I put my life into this community. Day and night. Do you think stapling flyers is free? Do you think organizing meetings and showing up for code inspections is free? I have sacrificed more for Mango Park than anyone. So if I took—hypothetically—a few reimbursements for my time and effort…” Her eyes flared. “Frankly, I deserve it.”

Velma watched her finish the sentence and let silence hang between them.

“Reimbursements,” Velma said softly. “Or embezzlement?”

Diane scoffed. “Oh, please. Big word for a bake sale coordinator. You don’t scare me, Velma. This is politics. You’re just jealous you lost the last condo board election. You can’t stand that people chose me to enforce the rules and not you.”

“I already filed an ethics complaint with the city housing authority,” Velma said. “And to be safe, I contacted the Mango Park police.”

Diane’s laughter died. “You did what?”

“The lieutenant is on his way here right now,” Velma said. “You like calling yourself the law in this neighborhood. Let’s see how you like meeting the real thing.”

“Over a few irregularities?” Diane exploded, voice rising. “You called the police on your own HOA president? Wake up, Velma. This is how the world works. People get compensated. You think anybody does this stuff for free?”

“I do,” Velma said. “And so do most of our neighbors. We volunteer. We care. We don’t write ourselves secret checks out of the pool fund.”

She closed her binder.

“I’d suggest you find your records,” she said. “The lieutenant is going to ask for them.”

“Please get a life,” Diane hissed. “You’re nothing but a jealous busybody.”

Velma smiled, small and satisfied.

“She’s going down,” she murmured as she walked out into the Florida heat.

By the time Lieutenant Sanchez pulled into Mango Park in an unmarked car, word had already traveled faster than any official notice ever had. Retirees out walking their dogs slowed to a crawl near the HOA office. Joggers suddenly found reasons to stretch within view of the front door. A teen on a skateboard sat inconspicuously on the curb, phone held suspiciously upright.

Inside, Diane was pacing her tiny office, flipping through a pile of invoices like she could rearrange the truth with sheer willpower.

When the door opened, she snapped, “If this is about pet waste, put it in writing, Velma!”

“Good morning, Ms. Morehead,” a male voice said instead.

She turned. The man in her doorway held up a badge.

“I’m Lieutenant Sanchez with the Jacksonville Police Department,” he said. “Mind if I come in?”

“Oh,” she said, smoothing her blouse. “Yes, of course. I wasn’t expecting—well. Did you have an appointment?”

“No,” he said, stepping inside. “But I’d like to take a look at your HOA finances.”

She laughed, too high, too sharp. “Well, sure, but I’m very busy, Lieutenant. Maybe we can schedule something with the board, do this in a more…formal manner.”

He set a folder on her desk and opened it. Numbers stared up. Copies of checks she’d signed. Vendor names she’d thought were safe. Bank account details she hadn’t realized anyone could tie back to her this quickly.

“According to these records,” he said, “$2,800 went to a consulting firm that doesn’t exist. Fifteen hundred dollars went to a landscaping company with a fake address. Both checks were deposited into your personal account. Can you explain that?”

She swallowed. The office felt suddenly too small, the AC unit too loud.

“Those were reimbursements,” she said slowly. “For my time. My effort. I work extremely hard for this community. Do you have any idea how many hours I put in? Day and night? This place would fall apart if I didn’t enforce the rules.”

“So,” he said, “you admit the funds went into your personal account.”

“I didn’t say that,” she snapped.

“You implied it,” he answered.

She threw up her hands. “Oh, I know what this is really about. This isn’t about numbers. This is about politics. It’s about that woman. Velma. She’s been gunning for me ever since I cited her for her illegal garden gnome.”

Behind Sanchez, the doorway filled with quiet satisfaction.

“Good afternoon, Diane,” Velma said. “You still keen on enforcing rules?”

Diane’s eyes went narrow. “You smug little—”

“Ma’am,” Sanchez cut in, voice firm. “This is a formal investigation. Please watch your language.”

“You can’t do this,” she said, panic starting to fray the edges of her words. “I’m the president of this association. I am the HOA enforcer. You need people like me here. Without me, it’s chaos. People will paint their front doors whatever color they want!”

“And yet,” Sanchez said, taking a pair of cuffs out of his belt, “the law still applies.”

He stepped behind her. “Diane Morehead, you are under arrest on suspicion of fraud and misappropriation of funds. You have the right to remain silent—”

She jerked away. “You can’t arrest me! This is entrapment! I need to speak to Captain Porter right now. He’ll tell you I keep this entire neighborhood running. I am the backbone of Mango Park!”

“Captain Porter is busy,” Sanchez said. “You’ll be dealing with me today.”

He clicked the cuffs around her wrists, the metal bright against her manicured hands.

Outside, people had drifted closer. Phones went up discreetly. Some not so discreetly. The teen on the curb recorded everything, eyes wide.

“You are all going to regret this,” Diane shouted as Sanchez guided her out the door. “You think you can run this place without me? You’re all sheep! Velma, you’re a jealous troublemaker. You’re the one who should be in trouble, not me!”

“Ma’am, please calm down,” one of the officers said, taking her elbow.

“I will not calm down!” she cried, heels catching on the concrete. “This is outrageous. This is a setup. I gave my life to this community. I deserve to be compensated. You—” She craned her neck toward Velma. “You are going to get yours, you hear me?”

“You’ll get your day in court,” Sanchez said. “For now, watch your head.”

He helped her into the back of the cruiser. She kept talking even as the door closed, her voice muffled but still sharp enough to cut through the Florida air.

Velma watched the car pull away, lights flashing silently. The “VOTE MOREHEAD” banner fluttered above her head, one corner coming loose, flapping like it suddenly understood the joke.

Every vote counts, Velma thought.

Maybe, she added silently, every receipt too.

The weeks that followed felt like one long episode of a neighborhood reality show nobody had realized they were filming. Mango Park’s Facebook group exploded. Half the residents shared stories of Diane’s over-the-top enforcement—photos of yard violations, quotes from emails demanding they change their patio furniture. The other half fretted about what would happen next.

“Who’s going to run the HOA now?” someone asked at the mailbox.

“Maybe someone who knows the difference between volunteering and stealing,” Velma said mildly.

City news stations picked up the story. “HOA PRESIDENT ACCUSED OF EMBEZZLING COMMUNITY FUNDS” scrolled along the bottom of the screen on the evening news, right between weather and sports. They showed a stock photo of a Florida subdivision that looked suspiciously like Mango Park and a close-up of a “No Parking on Grass” sign.

Velma watched the segment once. Then she turned off the TV and went back to her jigsaw puzzle.

She hadn’t done any of this for fame. She’d done it because she liked to sleep at night.

At the courthouse downtown, under an American flag and a seal that read IN GOD WE TRUST, a judge listened to arguments about charges and bail. Diane arrived in a county-issued jumpsuit the color of traffic cones, her hair pulled back, still insisting she was the true victim.

“It was just reimbursements,” she told the courtroom. “Everybody does this. I just made sure the community got quality services. My services.”

The prosecutor held up the bank statements. “Reimbursements,” she said, “are approved. These weren’t. These were secret checks written from dues-paying neighbors to Ms. Morehead’s pocket.”

The judge was not amused.

Back in Mango Park, life went on.

Grass still grew. Trash still needed to be taken out. Kids still rode scooters down the sidewalk. The pool tiles finally got fixed—properly this time, with an invoice from a real company Velma herself called and vetted.

The board held an emergency meeting in the clubhouse to vote on a temporary president.

“Velma,” someone said. “It should be you.”

She looked at the faces around her—people she’d argued with about paint colors, potlucks, parking. People who’d seen her walk into the HOA office and walk out with the lieutenant behind her.

“I don’t want to be president,” she said. “I’ll chair the finance committee. I’ll read every line of every invoice until my eyes cross. But I’m not interested in stapling flyers or ordering people to move patio chairs. I’ve done my part.”

They voted for a young mother named Tiana instead—someone with spreadsheets on her laptop and a calm voice.

Under Tiana, the “Vote Morehead” signs came down. The banner came down. New signs went up at the entrance:

MANGO PARK HOA

MONTHLY MEETING – OPEN TO ALL RESIDENTS

TRANSPARENCY • RESPECT • COMMUNITY

At the next meeting, Tiana stood up with a stack of freshly printed bylaw amendments.

“We’re adding term limits,” she said. “And we’re updating our oversight procedures. No more single-person approvals. No more mystery vendors. And definitely no more slush funds.”

Velma sat in the audience, hands folded, and smiled.

When Diane’s trial finally came, there were no camera crews in the courtroom. Just a handful of Mango Park residents in their nicest shirts, sitting behind the prosecutor. Diane’s lawyer tried to paint her as a tireless volunteer who’d simply gotten “confused” about boundaries between personal and community funds.

The jury, made up of people from all over Duval County who were tired of headlines about people mishandling money, looked at the bank statements. They looked at the vendor records. They looked at the woman who had once called herself “the law” in a subdivision.

Guilty, they said.

Misuse of funds. Fraud. A sentence long enough to ensure Diane would have plenty of time to think about what “reimbursement” really meant.

On the day she was transferred to state custody, Velma wasn’t there.

She was on her back porch in Mango Park, trimming dead leaves off her potted mango tree as the late afternoon heat settled in thick and sweet.

Her neighbor, Mrs. Lee, waved from the yard next door.

“Did you hear?” Mrs. Lee called. “They sentenced her.”

“I heard,” Velma said. “You sleep okay last night?”

“Best in months,” Mrs. Lee said.

Velma smiled. “Me too.”

Later, as the sun dipped behind the palms and the sky turned the exact color of the mangoes on her tree, Velma took a stroll down Mango Palm Drive.

She passed freshly painted mailboxes, a couple of kids chalking stars and stripes on the sidewalk, a man grilling in his driveway with a small American flag stuck in a flowerpot nearby. The pool gate stood open, laughter floating out. A little girl ran past her in a red swimsuit and stopped.

“Mrs. Richardson,” the girl said, breathless. “My mom says you’re the reason they fixed the pool.”

Velma laughed softly. “I’m just one of the reasons, honey. A lot of people helped.”

“Well, thank you anyway,” the girl said, and ran off.

Velma looked up at the entrance, where the old “Vote Morehead” banner had once hung. Now there was nothing there but blue sky and the clean white letters of the subdivision’s name.

Mango Park.

Clean. Safe. Orderly.

For real this time.

She walked home, her sensible shoes tapping against the Florida pavement, and thought about how, in the end, it hadn’t been a big speech or a dramatic showdown that changed things.

It had been a woman with a file folder, a lieutenant who listened, a community that decided rules weren’t a joke as long as they applied to everyone.

Diane had called herself the HOA enforcer.

In the end, it was the law that enforced itself on her.

And Mango Park, under the soft glow of porch lights and Florida stars, finally felt like what it was supposed to be all along: a neighborhood, not a kingdom.