The first thing that shattered wasn’t the glass, or the silence.

It was the smiley-face beaker on Mr. Navarro’s desk.

One second it was just sitting there, a goofy yellow cartoon grin staring out over twenty-eight juniors in an ordinary American chemistry class, U.S. flag drooping in the corner, fluorescent lights buzzing like always. The next second, the intercom crackled, and our entire world snapped in half.

“Lockdown. Active threat on campus. This is not a drill.”

The words didn’t sound real. They sounded like something from the news—those headlines you scroll past about some other high school in some other state, somewhere else in the United States where people light candles near chain-link fences and say they never thought it would happen here.

Except it was here. In our town. In our hallway.

For one heartbeat, nobody moved.

Then everything happened at once.

Chairs scraped. Desks screeched. Someone dropped a textbook that hit the floor like a gunshot and made three people gasp. Anne’s hand clamped around my arm as we dove to the ground. Mr. Navarro sprinted to the door, slammed it shut, twisted the lock until his knuckles went white, then killed the lights with a sharp click.

The room fell into instant darkness, the kind that feels heavier than air.

I ended up wedged under a lab table between a cabinet and Anne’s shaking knees. Her breath hit my cheek in sharp, panicked bursts. “Oh God. Oh God,” she whispered, over and over, like it was the only sentence she remembered how to say.

Somewhere in the building, something popped. Once. Twice. Three times.

Nobody in that room had to ask what the sound was.

Anne’s fingers dug into my forearm so hard I felt her nails break skin. Hot stinging pain registered somewhere far away, like it was happening to someone else. My brain was stuck on one thought, repeating in a loop:

Josh is in the gym right now.

Second period. Same schedule since freshman year. He always had gym when I had chem.

Josh in the gym. Pops from the gym building.

I tried to shove that thought down, deep and hard, where it couldn’t touch me. I was trapped in a dark classroom with no way out and thirty-two people whose panicked breathing made the air feel thin. I couldn’t afford to think about my best friend right then.

“This is real,” someone whispered from the row behind us. “This is actually real.”

The emergency strobes in the hallway bled faint red light around the edges of the door window, painting everything in ghost colors. Anne’s phone lit up under her chin, blue-white glow shaking in her hands as she texted her mom.

Her thumbs tapped out I love you like it might be the last message she ever sent.

I dug my own phone out with clumsy fingers. The screen glared too bright in the dark, the signal bars spinning uselessly. I typed so fast I hit half the wrong keys:

Are you okay?

No name, no punctuation. Just those three words, sent to the contact I’d had pinned to the top of my messages list since middle school.

Josh.

The message didn’t deliver. Just sat there with a little gray “sending…” under it that felt like a slap.

At lunch, he’d asked to borrow my car again. I’d said no again. He’d shoved his tray away and muttered something about never asking for anything. I’d said, “Maybe try paying back the last time first, pathetic,” loud enough for the whole table to hear.

People had laughed. Tyler had laughed the loudest.

Josh’s face had closed off like a door slamming.

What if that was the last thing I ever said to him?

More pops. Louder this time. They reverberated through the floor, rattling the metal legs of the desks, echoing down the thin American high school walls that had never been built for this.

“My sister says there’s one in the gym,” the kid next to me whispered, shoving his phone toward us. The screen showed a message, neon green bubble in the glow. She’s in the equipment closet. She says he’s in the gym.

He. As if everyone already knew Josh’s gender without knowing his name.

My stomach turned to concrete.

We waited. Ten minutes. Fifteen. Time stretched out, then snapped back. At one point, distant footsteps thundered down the hallway, then slowed, then stopped.

The handle on our door rattled.

Every muscle in my body locked. Something hot and wet slid down my wrist—either sweat or blood from where Anne’s nails had dug into me. Someone in the dark let out a strangled sob.

“Police,” a voice shouted from the other side. “Stay locked down. Stay quiet.”

The footsteps moved on, radio static crackling faintly as they went.

“They’ll get him,” Anne breathed, like she was praying. “They have to. They’ll stop him.”

But the girl squished into the shadow of the supply closet door shook her head, her face visible for a second in the glow of her phone.

“My boyfriend’s in the office,” she whispered. “He says the shooter knows all the back corridors. Service hallways. Stuff the cops don’t even know about.”

My skin crawled. Our school suddenly wasn’t a place I knew. It was a maze, and somewhere in it, someone with a gun knew the shortcuts better than the people trying to stop him.

Pops. Closer now. Glass breaking. Someone screaming—sharp, high, sudden—and then nothing. The silence that followed was worse than the scream.

“My God,” the girl by the window whispered, reading her phone. “They’re saying… multiple people shot.”

“Don’t,” I said, my voice cracking like the frosted glass in the chem lab door. “Don’t say that.”

Because once you said it out loud, it was real.

Messages flooded our group chat. Antonio: Has anyone heard from Josh?

No.

No.

No.

Josh pls answer.

My thumbs trembled over the screen.

Josh. Answer me. Please.

Nothing.

Forty-five minutes after that first crackling announcement, the sirens outside were a constant wail. The shooting… hadn’t stopped. It moved through the building like a storm, thunder rolling closer then fading, closer then fading. These weren’t random bangs anymore. They were patterns. Directions.

The fire alarm suddenly shrieked to life, a piercing mechanical howl that made us all flinch.

The lights stayed off.

The alarm cut out mid-wail, choking to silence as if someone had ripped it out of the wall.

“He’s on the third floor,” someone breathed, reading from their phone. “Science wing. Room by room.”

“That’s above us,” Anne whispered. “He’s going to come back down.”

As if answering her, heavy footsteps thudded overhead. Dust sifted down from the ceiling tiles onto our hair, our shoulders. The footsteps paused, then moved, like whoever was up there was tracing the floor plan with his weight, mapping where we were without ever seeing us.

“He has a list,” the girl with the boyfriend murmured. “They’re saying he has a list. He’s looking for specific people.”

My mind flashed through faces. Coach Henderson’s red baseball cap. Tyler’s smirk. Josh’s lopsided grin from our middle school yearbook. Drifting further apart each year.

Seconds later, footsteps pounded down the stairs at the end of our hallway—fast at first, then slow, deliberate, like whoever it was knew exactly which door they were walking toward.

Everyone went absolutely still.

The footsteps stopped right outside our room.

The handle turned. Once. Twice. Rattling against the lock.

Someone muffled a sob behind their hands.

The handle stopped shaking. A pause stretched so long that my lungs burned.

Then the footsteps moved on, echoing down the corridor.

“We’re going to die in here,” Anne whispered against my shoulder. “We’re actually going to die in here.”

But an hour passed, then another five long minutes, and somehow we didn’t. We sat there in blacked-out silence under cheap American-issue lab tables, muscles seizing from the strain of holding still, while the world outside our door exploded and rearranged itself out of order.

“He’s in the main hallway,” the girl with the boyfriend hissed. “Heading for the math wing.”

The math wing connected directly to ours by a short stretch of lockers and bulletin boards about SAT prep and prom tickets and college fairs. Ordinary things that now felt like props in a horror movie.

“Turn off your phones,” Mr. Navarro whispered. “No light. No sound. Nobody move.”

Screens winked out, one by one, until we were plunged into absolute dark. No glow. No red exit signs. Just the taste of dust and fear.

I could hear anything and everything: my own heartbeat pounding in my ears, Anne’s ragged breathing, someone whispering a Hail Mary in Spanish under their breath, the distant static of police radios, a faint wail from outside that could have been a siren or a parent.

Then the footsteps came back.

Slower now. Closer.

They stopped in the classroom next door.

The door handle rattled. A heartbeat later, the sound of glass exploding punched through the wall. We heard boots crunching over shards, chairs scraping, furniture slamming aside. Drawers yanked open. A desk overturned, then another, like he was hunting through the room piece by piece, looking for specific faces.

Anne’s hand found mine and squeezed so tightly I felt the bones in my fingers grind.

Our door rattled next.

The lock held.

For a heartbeat there was only the sound of his breathing on the other side, amplified by the silence.

Then three hard blows slammed against the door.

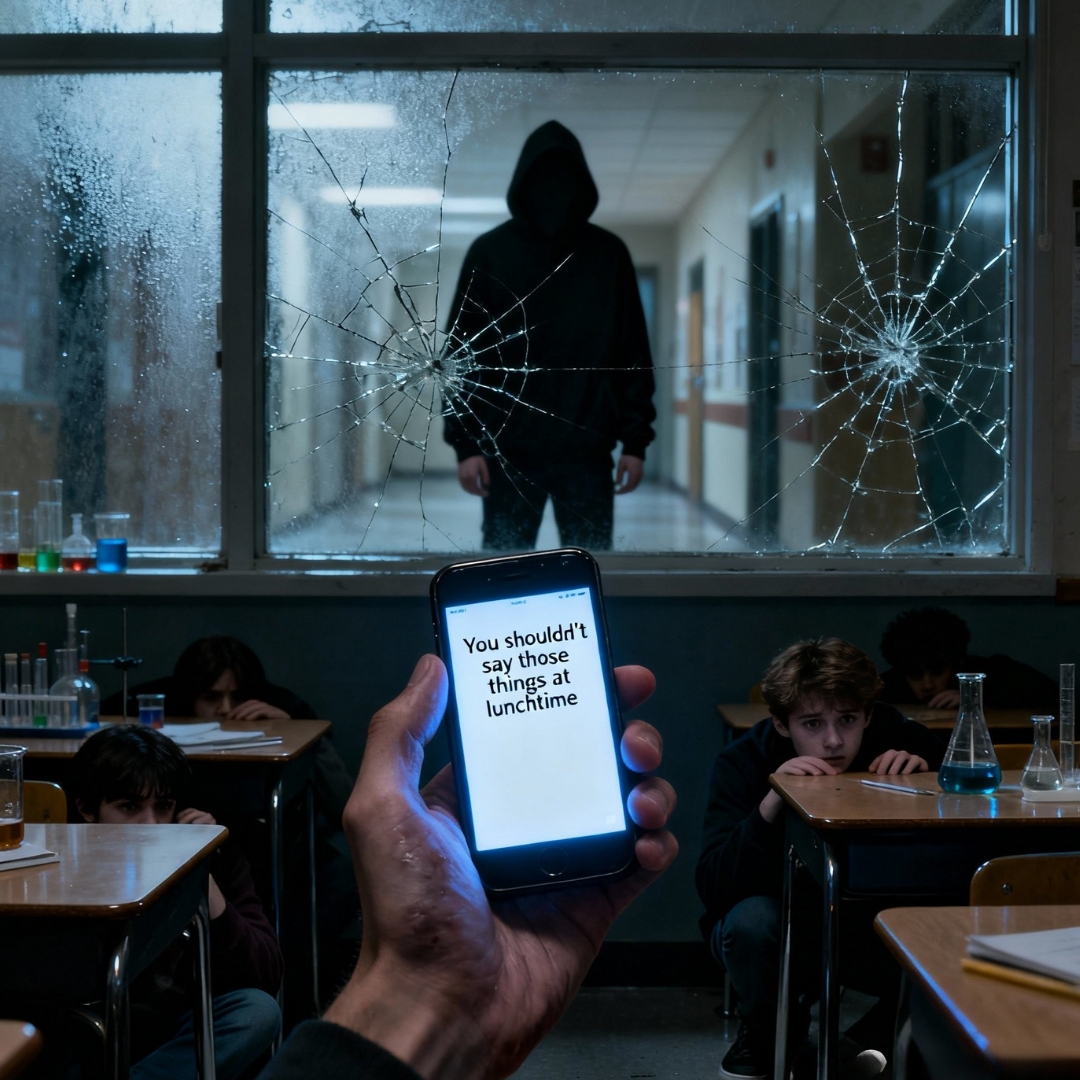

The frosted window above the handle cracked, spiderwebbing but not fully breaking. Through the fractured glass, a shadow appeared: human-sized, broad-shouldered, wearing a hood. Too short to be a cop. Too thin for Mr. Navarro.

A student.

Something in the silhouette—a tilt of the head, a curve of the spine—tugged at me with horrible familiarity, but my brain refused to connect the dots.

The shadow shifted. Raised something toward the glass.

This is it, I thought. This is how it ends. In an American public school classroom with a crooked periodic table and half-finished homework in my backpack.

My phone, which I was sure I’d powered off, flashed to life in my palm. The notification sound was a tiny chirp, but in that dead silence it might as well have been a grenade.

Every head snapped toward me. Harsh whispers: “Turn it off. Turn it off, what are you doing—”

But I couldn’t move. I couldn’t breathe. I could only stare at the message on my screen.

From: Josh

You shouldn’t have said those things at lunch.

A simple sentence. Eleven words.

Outside the glass, the shadow shifted its weight, that familiar curve of the shoulders I’d seen a million times in cafeteria lines and hallways and on my parents’ driveway when we were late for practice.

The black hoodie was the same one I’d given him for his birthday last October, the one with the faded NBA logo and the too-long sleeves he’d shoved his hands into when he was nervous.

The world tilted.

My best friend since third grade was standing on the other side of that cracked piece of glass with a weapon in his hands.

My throat closed. My thumbs hovered uselessly over the keyboard while my brain screamed No, no, no, anyone else, please anyone else.

Next to me, Anne leaned in, seeing the light reflected on my face. “What?” she breathed. “What’s wrong?”

My mouth wouldn’t shape the words. Couldn’t turn my thoughts—Josh, it’s Josh, it’s him—into anything that could be spoken aloud.

My fingers shook so hard I almost dropped the phone before I managed to type back.

This isn’t you.

Please. This isn’t who you are.

Three dots appeared at the bottom of the screen almost immediately. Disappeared. Reappeared. Like he was typing, stopping, deleting, typing again.

Outside the glass, the shadow finally moved. Footsteps retreated, slow and measured at first, then faster. Away from our door and down toward the math wing.

I didn’t feel relief. Just a new kind of terror: Josh is out there. Josh is still moving. Josh is not done.

I knew his route options without even thinking about it. Six years of walking these halls together had mapped them into my muscle memory. From the chem wing to the math wing was two minutes at his usual pace.

Two minutes.

I made a decision that didn’t feel like a decision at all—more like a reflex.

I opened our group chat and typed as fast as my shaking hands would allow.

It’s Josh. Black hoodie. He’s heading toward the math wing right now.

Forward this to 911. Now.

My thumb hit send before I could talk myself out of it.

Antonio responded in under three seconds. On it. Sending.

Under my message, the tiny gray word changed from delivered to read.

Mr. Navarro was crawling toward me through that narrow canyon between the rows, probably ready to whisper-yell at me for breaking lockdown protocol, for not keeping my phone dark and hidden.

I tilted the screen so he could see it.

His face went white, bleached by the blue glow. All the color vanished like someone had pulled a plug. For a second, he just stared at the message thread—at Josh’s name, at the last line he’d sent. Then he looked at me. Really looked, like he was seeing me for the first time as more than just a student with half-finished homework.

“Keep him talking,” he whispered. “If you can. Buy time.”

The idea hit me like a punch.

Negotiate. With the person I used to share Pop-Tarts with before the bus came. With the kid I’d built a treehouse with, stealing lumber from behind my neighbor’s Home Depot–sized shed. With the boy who once biked three miles to my house at midnight because I texted that my grandpa had died and I couldn’t stop crying.

“My teacher just told me to… to negotiate with him,” I breathed, the words barely sound.

But my hands were already moving, typing another message.

Where are you?

Talk to me. Please.

Dots. Disappear. Dots again.

Each flicker made my heart jackhammer harder. Was he answering me, or deciding whether to come back and kick that glass in?

When his reply finally landed, I had to read it three times before the meaning sank in.

Coach Henderson first.

Then that jerk Tyler who laughed at lunch.

Then maybe I’ll decide about you.

The casual way he listed their names—like a to–do list—made my stomach twist.

I pictured Coach Henderson with his whistle and his American-flag ball cap, the guy who gave me rides home when my parents worked late. I pictured Tyler in his letterman jacket, leaning back in his chair and laughing when I called Josh pathetic.

It was twisted, sick logic—but it was logic all the same. One insult at lunch, and Josh had arranged the names like puzzle pieces until they made sense to him.

None of that made it okay.

Gunfire crackled again, distant but unmistakable. Someone in our room started crying loud, ugly sobs that tore straight through the darkness.

“Shh,” Navarro hissed, crawling over to clamp a hand gently over the kid’s mouth. “You’re okay. Just breathe. You’re okay—we’re here, we’re here.”

I typed like my fingers were on fire.

I’m sorry about lunch.

I was being a jerk. Tyler was worse.

I should have stood up for you.

Please don’t hurt anyone else. Please just stop.

Dots.

I held my breath until my chest burned.

His next message was longer. Lines of text stacked up, filling my screen with every word I’d never noticed in his eyes.

You think sorry fixes everything?

One apology makes up for three years of you getting cooler while I stayed the loser everyone laughed at?

Varsity soccer.

Homecoming king.

New friends.

You forgot about me unless you needed something.

Each sentence landed like a punch. Images flashed: me tugging on a varsity jacket while Josh sat in the stands alone. Me at a bonfire party with Emma’s hair in my lap while Josh’s last “you up?” text sat on read. Me sitting at lunch with a whole table of people while he sat two tables over with his earbuds in.

Police radios crackled somewhere in the hall, words half heard: suspect heading toward athletics… units moving… copy that… south stairwell—

They were tracking him. They had to be. Antonio had sent my messages. Somewhere out there, a dispatcher’s screen was flashing with Josh’s name, our location, the word math wing in red.

Where are you now? I typed. Are you safe?

His response came almost instantly.

Since when do you care if I’m safe?

If I’d had any illusions that he was still the same Josh beneath the black hoodie—that with the right words, I could pull him back—they died right there on that line.

Boots thundered past our door. A single shot rang out, so loud it made my vision flash white. Someone shouted, “Officer down!”

The words hung in the air like smoke.

My whole body went cold. Josh had just turned his weapon on a cop. There was no going back from that, no plea deals or “tragic misunderstanding” headlines. The stories I’d watched on CNN—on those giant touchscreens with infographics about weapons and timelines—flashed through my mind.

This only ends one of two ways now, I thought. Prison. Or a body bag.

I swallowed hard and typed again.

Please. Just stop.

Turn yourself in.

This doesn’t have to get worse.

We both knew that was a lie. It was already as bad as it gets in an American high school: sirens, barricades, text alerts going out to parents in all caps.

Dots. They appeared and disappeared over and over, like he was pacing with his thumbs.

When his next message came, it made my blood run colder than anything before.

Are you still in Navarro’s room?

Second-floor chem lab?

My heart stuttered. He was confirming my location. The list in his head wasn’t just names; it was rooms, stairwells, routes.

Yes.

Please don’t come here.

Cops are everywhere now.

You can’t win this.

His answer slid in with terrifying calm.

I’m not trying to win.

I’m trying to make people feel what I felt.

Something inside me broke.

This wasn’t about escape or ransom or demands. This wasn’t some Hollywood scenario where the hero talks the villain down. This was pain, sharpened into something lethal, aimed at anyone who’d ever made him feel small.

I forwarded his last three messages to Antonio with a single line: Tell 911 he’s talking about the chem lab.

On the screen, Antonio’s reply popped up. On phone w/ dispatcher right now. Sending.

Outside our classroom, heavy boots pounded up the stairwell. “SWAT moving to second floor,” someone shouted. “Set up perimeter—suspect believed near science wing.”

Navarro started moving people in the dark with urgent gestures, pointing to the storage closet in the back corner—our only real blind spot from the door. He squeezed fifteen students inside, then tried to cram more, stacking bodies like sandbags.

Glass shattered somewhere close. We all flinched.

“He’s back on our floor,” someone whispered.

We heard the pattern of his movements: heavy breaths, desks scraping, things being thrown aside. Searching. Each empty doorway making him angrier.

My phone buzzed once more.

A photo this time.

Taken from the hallway. Our classroom door, its frosted glass a spiderweb of cracks. Through the blur, the edge of Navarro’s desk, and above it, the periodic table poster we’d hung in September during detention, still crooked.

Caption: I can see your teacher’s desk from here.

Crooked poster’s still there.

My fingers trembled.

That poster’s been crooked since September.

You helped me hang it during lunch detention.

Remember?

I was desperate for a foothold. A memory. Something different from gunfire and sirens and the list in his head.

Dots. They stayed, blinking, longer than they ever had.

Next to me, Anne peered at the screen with wide eyes. “What’s he saying?” she whispered.

I didn’t answer. I couldn’t. It felt like any sound might shatter whatever thin connection I had left.

His reply finally came.

You got detention for spray painting the parking lot.

I got detention for standing next to you.

We were never the same after that.

He was right. I’d thought it was funny—painting our class year across three parking spaces in giant blue numbers. I’d bragged about it. The principal had caught us. I’d been the one holding the nearly-empty spray can, paint still wet on my hands, but Josh had refused to snitch.

We’d both sat in that Saturday detention, joking at first, until I started talking about how “worth it” it was. He hadn’t said much after that.

I never thought about how unfair it was that he took the hit for something he didn’t do. Not really. Not until that moment, kneeling on a tile floor, trying not to pass out from fear.

You’re right, I typed.

I got away with stuff.

You took the blame.

That wasn’t fair.

But this won’t fix it.

Before his response could land, the hallway erupted. An explosion—something louder than a shot, closer than a siren—made the floor vibrate. Anne screamed. My ears rang.

“Suspect spotted south stairwell!” a voice shouted. “Move! Move!”

Josh’s next message was short.

Gotta go.

Cops finally found the back stairs.

There was a sick little joke tucked between those words, like hide-and-seek had finally gotten interesting.

Please, I hammered out, thumbs flying. Please just give up.

I’ll visit you.

I’ll tell them you were bullied.

I’ll say anything that helps. Just stop.

The message ticked from sending to delivered.

It never turned to read.

Three more shots cracked through the building. A shout: “Shots fired! Officer needs medical!” Footsteps. Radio chaos. Words tumbling over each other about securing a suspect, perimeter, EMS en route.

We waited in the dark, every second stretching thin.

Ten minutes later, someone hammered on our door.

“Police!” a voice yelled. “We have the suspect in custody. Prepare for evacuation!”

Nobody moved.

“Stay down,” Navarro hissed. He crawled to the door, squinted through the fractured glass at uniforms and badges, at the familiar Texas-shaped patch from our state troopers mixed in with the Sheriff’s Office insignia. Only when he was sure did he unlock the door with trembling fingers.

Two SWAT officers swept in, all armor and helmets and rifles held ready. They checked corners, closets, under the lab tables, then finally nodded.

“Single file,” one of them ordered. “Hands visible. Eyes forward. Do exactly what we say.”

We stood on legs that barely remembered how to work. Moving from under that table into the harsh hallway light felt like stepping out of a cave.

The hallway looked like something from those U.S. breaking news shots they always cut to: glass shattered across linoleum, lockers dented, ceiling tiles hanging askew. Dark stains I refused to look at too closely.

“Keep your eyes up,” an officer said. “Don’t look at the ground. Keep moving.”

Anne’s fingers threaded through mine again, squeezing so hard my knuckles popped. I didn’t let go. If she needed something solid to hold onto, so did I.

As we turned the corner toward the main stairwell, I saw him.

Four officers knelt around someone on the floor in a black hoodie. Hands cuffed behind his back. Face pressed to the tile. A mark on his temple, reddened and swelling. His eyes were open, scanning the hallway in quick, jerky movements like he was still looking for someone.

For me.

For just a second, our eyes caught.

I didn’t see the shadow behind the cracked glass, or the names in that text message, or the hoodie at the end of the hallway. I saw Josh. My Josh. The kid who’d fallen out of our treehouse and laughed even as he limped. The boy who’d shown up with ice cream when my dog died.

He looked small. Young. Terrified.

Then a deputy stepped into my line of sight and nudged our line forward.

We walked past Coach Henderson’s office. Paramedics were crowded inside, bodies blocking the view of whoever was on the floor. I stared straight ahead. I wasn’t ready to know.

The front doors yawned open, sunlight flooding the entryway so bright it made my eyes water. Outside, the parking lot had turned into something that looked more like a war zone than the place where students practiced reverse parking for their road tests.

Ambulances. Fire trucks. County sheriff cars with their light bars spinning. A mobile FBI command vehicle with satellite dishes raised. News vans from every local station, their logos shouting in red, blue, and yellow.

They led us to a taped-off area with folding chairs and crisis counselors in neon vests. Blankets. Plastic water bottles. Clipboards.

Anne spotted her mom across the crowd—she’d pushed up against the police line, face blotchy and frantic. The second they saw each other, Anne started crying again, but this time the sound was different. Less panic. More relief.

I looked down at my phone.

Seventeen missed calls from Mom. A stack of texts:

Are you okay?

Please answer.

Where are you?

Please, please answer.

Please be alive.

My hands shook as I hit call. She picked up before the first ring finished.

“Nate?” Her voice was raw and breaking. “Nate, is that you?”

“I’m okay,” I said, even though I wasn’t sure what okay meant anymore. “I’m outside. I’m… I’m safe.”

I heard my dad’s voice in the background, muffled and frantic: “Is it him? Is he alright?”

“It’s me,” I said louder, forcing the words out through the tightness in my throat. “I’m okay.”

They said they were coming, but traffic was backed up for miles. Every road into our sleepy Midwestern town was clogged with squad cars, ambulances, news trucks, and parents blowing through red lights.

While I waited, I watched four ambulances pull away from the front doors one after another, sirens wailing. I stopped counting after the fourth because each one felt like a number I didn’t want to know the answer to.

Near the edge of the crowd, the girl who’d been at the window in our classroom stood with a news reporter. The reporter’s hair was perfect, her voice bright even with the gravity in her words. The lower-third graphic on the screen strapped to their camera read:

BREAKING: SCHOOL SHOOTING IN MIDWESTERN TOWN

SEVERAL DEAD, DOZENS INJURED

The girl’s voice shook as she said, “We thought we were all going to die. We thought—”

A police officer stepped between them, pushing the camera crew back. “Let the kids breathe,” he snapped.

Antonio found me, shoving his way through a knot of students wrapped in Red Cross blankets. He didn’t say anything. Just pulled me into a hug that felt like it might hold me together.

When my parents finally reached the staging area, my mother grabbed me so hard my ribs creaked. My dad kept touching my face, like he was afraid I’d flicker away if he looked away.

“Are you hurt?” he asked for the third time as we walked past the TV satellite trucks toward our car.

“No,” I said automatically. It wasn’t true, but the places I hurt weren’t bleeding.

On the drive home, we passed people gathered on corners, phones out, watching the line of emergency vehicles. Helicopters droned overhead. Every news notification that buzzed my phone used the same words: tragedy, devastated, active shooter, small American town.

At home, the neighbors stood on their porch, whispering as we pulled into the driveway. I realized this was it now. This was who I was, in their eyes. The kid who’d been there when it happened.

The kid whose best friend did it.

Inside, I headed straight for my room, but my parents stopped me. “Stay where we can see you for a while,” my mom said. Her voice was gentle but firm.

We sat in the living room with the TV on mute, watching aerial footage of my high school from a news helicopter, the U.S. flag out front hanging at half-mast already. A red banner pulsed at the bottom of the screen with names as they were confirmed.

Coach Michael Henderson – deceased.

Tyler Morrison, 17 – deceased.

My chest clenched. Josh’s list, in white letters across the bottom of the screen.

My phone buzzed again and again. Group chats exploding. People from classes I barely remembered texting:

Are you okay??

Were you there??

Is it true you were texting him??

Somebody asked in the main school group chat: Did anyone else know Josh was planning this? Three people tagged me, like my silence meant I’d been in on it.

I typed, hands trembling. I didn’t know anything. I’m as shocked as everyone.

I hit send and stared at the words. They were true. They also felt like a defense, like I was protecting myself while two people lay in hospital morgues.

Clark from gym class typed back immediately: But you were texting him during it. What did he say?

Everyone wanted the same thing—the story. The texts. The details. They wanted to dissect Josh’s messages like a crime podcast.

Sarah from English chimed in: Did he seem different lately? Did you see warning signs?

Notifications stacked so fast I couldn’t keep up. Accusations. Curiosity. Fear.

It felt like being back in that hallway, surrounded on all sides.

I held down the power button until my phone went black.

Silence settled over our living room, heavier than any TV commentator’s voice. My hands were still shaking.

An hour later, my mom called us to the kitchen. She’d made pasta on autopilot, the same recipe she used for every soccer win and birthday and random Tuesday.

None of us ate.

The clock on the wall ticked too loudly. The refrigerator hummed like it was mocking us with normal noises.

“Do you want to talk about it?” my dad asked finally.

I shook my head. How was I supposed to explain any of it? That my best friend had turned our school into a crime scene. That I’d read his list in real time. That I’d seen him on the floor in cuffs and still couldn’t reconcile that image with the boy who used to sleep on my couch during Xbox marathons.

That night, sleep was a joke.

Every time I closed my eyes, I was back under that lab table. The frosted glass spiderwebbing. Josh’s hoodie outside my door. The list. Coach Henderson’s office. Tyler’s name on the news crawl.

At 2 a.m., I gave up on pretending.

Downstairs, my dad sat on the couch in the dark, the TV still tuned to national news. Images of our high school flickered across the screen. Aerial shots. Interviews with shaken students. Pictures of Coach Henderson and Tyler taken from yearbooks, birthday parties, Facebook profiles now frozen in time.

They blurred into every other U.S. school shooting graphic I’d ever seen.

My dad didn’t look surprised to see me. He patted the couch. I sat. We watched in silence.

At sunrise, my mom came downstairs with her phone, eyes red-rimmed. “School’s canceled for the rest of the week,” she said. “There are crisis counselors at the community center this afternoon.”

She looked at me in that way that meant it wasn’t a suggestion. “You’re going,” she said softly. “You need to talk to someone…someone who does this for a living. Not just us.”

I wanted to argue. To say, I’m fine, I’m fine, I don’t need to sit in a room and pick apart everything I did and didn’t do.

But I heard the quaver in my own breath and knew she was right.

The community center gym smelled like disinfectant and fear.

Tables lined the walls. Counselors in cardigans and ID badges sat behind clipboards. Students and parents filled out forms, eyes vacant, hands shaking. News cameras hovered outside, lenses pressed against the glass doors.

A woman with gray-streaked hair and kind eyes called my name. “I’m Cecilia,” she said. “Come with me.”

She led me to a small office off the gym. No posters. No inspirational quotes. Just two chairs and a box of tissues.

“I’m not here to push you,” she said when I sat down. “I’m here to listen. Start wherever your brain is stuck.”

“Guilty,” I said without thinking. “I feel… guilty.”

She nodded once. “What do you feel guilty about?”

The list spilled out, faster than I could stop it.

Calling Josh pathetic at lunch.

Laughing when Tyler did.

Not noticing he was drowning right next to me.

Texting him during the lockdown instead of hiding silently.

Forwarding his messages to Antonio and the police.

Testifying would come later, but even then I knew it was on the list.

“Surviving when they didn’t,” I finished in a whisper. “Being his friend all those years and never seeing this coming.”

Cecilia listened without interrupting, hands loose in her lap.

When I finally ran out of words, she let the silence sit for a moment, like she was making space for it.

“You didn’t pull the trigger,” she said at last. “He did. Josh made his own choices. Your words at lunch were unkind. They did not cause this.”

I wanted to protest. To point to the messages. The list. The way he’d underlined “Tyler” like he was circling a final exam answer.

“People who plan attacks like this,” she continued quietly, “don’t start planning because of one insult. They look for reasons to justify what they’ve already decided to do. If it hadn’t been that word, it would have been something else.”

I wanted to believe her. That I hadn’t been the final straw.

But the guilt sat heavy on my chest like a weight.

She taught me grounding techniques. Five things you can see. Four things you can touch. Three things you can hear. Two things you can smell. One thing you can taste. Slow breathing. How to spot when my brain was sliding back into that hallway and gently pull it forward again.

She handed me a small spiral notebook. “Write the things you can’t say out loud,” she said. “Especially the ugly ones. Especially the ones that scare you.”

Before I left, she scheduled me for twice-weekly sessions. Tuesdays and Thursdays. She wrote her number on a card and said, “Call if you feel like you’re back in that hallway and can’t get out.”

When we walked out of the community center, a reporter with perfectly curled hair and a microphone stepped toward me. “Excuse me,” she called. “You were Josh Taylor’s friend, right? Did you see warning signs? Do you feel responsible for not stopping him?”

My dad stepped between us like a wall. “Back off,” he snapped.

I turned my face away, jaw clenched, because I refused to give them the money shot of me breaking down. My phone buzzed.

Antonio: Don’t talk to reporters. They’re trying to blame us for what he did.

That night, there was a candlelight vigil at the park. American flags at half-mast, candles in paper cups, faces lit from below. Photos of Coach Henderson and Tyler propped on folding tables, surrounded by flowers and teddy bears and handmade posters.

Someone handed me a candle. The wax burned my fingers as it dripped, but I welcomed the sting. It felt real.

The principal made a speech about community and resilience and how “this is not who we are,” even though it very much was now. Tyler’s girlfriend sobbed in the front row. Coach’s wife stared straight ahead like she’d turned to stone.

I lingered at the back, hoping I could be invisible.

It didn’t last.

A woman I didn’t recognize walked straight up to me. Her eyes were red, but there was anger burning behind them.

“Are you the boy who was texting him?” she asked.

I nodded, because lying wouldn’t change anything.

“Did you try to stop him?” Her voice came out sharp.

“Yes,” I said. “I did. I tried to keep him talking. I sent his messages to the police. I—”

She turned away before I finished, shaking her head like none of it mattered.

That was when I understood something I would keep relearning in the months to come: some people would always blame me. For what I didn’t know. For what I did. For what I didn’t do.

For not seeing it. For seeing it too late.

I left before the speeches ended.

Two days later, Detective Jared Morgan from the county sheriff’s office called. He had a calm voice, the kind you see in press conferences when they stand at a podium with a bunch of flags behind them.

“We’ll need your testimony at the preliminary hearing,” he said. “We’ll walk you through it. You won’t be alone.”

Preliminary hearing. Trial. Words I’d only heard on Law & Order reruns were suddenly written in ink across my calendar.

My mom drove me to buy dress pants and a button-up shirt that didn’t feel like mine. In the courthouse parking lot, news vans lined up like a parade. Protesters held handmade signs: JUSTICE FOR VICTIMS. MENTAL HEALTH MATTERS. END SCHOOL VIOLENCE.

Inside, we sat in a witness waiting room with bad coffee and old magazines. When they finally called my name, my hands shook so badly I shoved them in my pockets.

The courtroom looked exactly like every courtroom on TV and nothing like it at the same time. Dark wood. Seal of the State of Ohio on the wall behind the judge. People packed into the benches—students from school, parents, reporters, strangers.

Josh sat at the defense table in an orange jumpsuit, hands cuffed, his hair shorter than I’d ever seen it. He looked smaller than he had in the hallway. Younger.

He looked up when I walked in. Our eyes met. The fear in his face was a mirror of my own.

I raised my right hand and swore to tell the truth.

The prosecutor asked how I knew Josh, and I told her: third grade science partners. Sleepovers. Treehouses. Backyard football. Halo marathons. Then high school came and everything shifted—varsity jackets, parties, new friends, while he slid quietly out of the frame.

She asked about that lunch.

“He asked to borrow my car,” I said, my voice thin. “I said no. He got mad. I called him pathetic. People laughed. He walked away.”

She showed me printed copies of our texts. The paper shook in my hands as I read them aloud in open court.

You shouldn’t have said those things at lunch.

Coach Henderson first. Then that jerk Tyler. Then maybe I’ll decide about you.

I’m not trying to win. I’m trying to make people feel what I felt.

You could have heard a pin drop.

“How did you feel, reading those messages?” she asked.

“Terrified,” I said. “I tried to keep him talking. I forwarded everything to a friend who was on the phone with 911. I thought maybe… it could help them find him faster.”

The defense attorney asked if Josh had been bullied. I said yes. He asked if I had ever bullied him. Under oath, I said yes again.

“What did you call him?” he asked.

“Pathetic,” I said, the word sour on my tongue.

“Do you think your client’s mental state—” he began, but the prosecutor objected. The judge sustained it, reminding him I wasn’t a doctor.

Still, the question hung there like smoke.

After the hearing, Morgan pulled me aside. “You did the right thing,” he said. “Your texts helped us track him. They may have saved lives.”

It didn’t feel like the right thing. It felt like I’d been thrown into the middle of a story genre we all know too well in this country, the kind that starts with a name and a headline and ends with life in prison.

Back at school, everything was different.

Some kids called me brave in the hallways. Others turned their backs. One morning, I found the word SNITCH spray-painted across my locker in red.

The principal gave me a new locker. Security reviewed footage. Someone whispered that it was one of Tyler’s friends who did it. Nobody proved anything.

Antonio and Anne walked me between classes like unofficial security detail. “People are picking sides,” Antonio said one afternoon. “Some say Josh is a monster. Some say he’s a victim. They don’t know what to do with you, so they throw paint.”

In therapy, Cecilia asked how I felt about testifying.

“Guilty,” I said, because that answer never seemed to change.

She leaned forward. “You can care about Josh and still hold him accountable,” she said. “Those things aren’t opposites. You can feel compassion for his pain and still acknowledge he chose violence.”

“He was bullied,” I said. “We all saw it. I helped.”

“He was bullied,” she agreed. “And he planned a shooting. Two truths can exist at once. Your responsibility is yours. His is his.”

She made me say it out loud:

I am responsible for what I said at lunch.

Josh is responsible for bringing a gun to school and pulling the trigger.

Some days, I believed it. Other days, the guilt wrapped around me like barbed wire.

The trial started three months later.

Three days of testimony. Three days of cameras outside the courthouse, satellite dishes pointed at the gray Ohio sky. National cable shows parked across from our town diner. Commentators talking over graphics labeled TIMELINE and MOTIVE.

I testified again, this time for nearly four hours. The prosecutor walked me through every detail: the lunch fight, the texts, the noises in the hallway, the way Josh knew which stairwells to use.

“He had a list,” she said. “He moved with purpose. Do you believe this was planned?”

“I’m not an expert,” I said. “But it felt… deliberate. He knew where I was. He knew who he was looking for.”

The defense attorney focused on different details. Every mean thing I’d ever said. Every time I’d chosen a party over hanging out. The times I’d seen Josh sitting alone and not walked over.

“Would you say he felt invisible?” he asked.

“I don’t know what he felt,” I said. “I know what he did.”

He asked if fear and trauma could make a person think ahead and still be mentally unstable. I said I didn’t know. I meant it.

When the jury came back six hours into deliberation, my stomach knotted.

Guilty on all counts: first-degree murder for Coach Henderson. First-degree murder for Tyler. Attempted murder of a police officer. A list of charges so long the clerk’s voice turned hoarse reading it.

Josh stood there, hands cuffed, face blank. Behind him, his mom broke apart. In the opposite row, Coach’s wife and Tyler’s parents clung to each other like they were the only things keeping each other upright.

Two weeks later, at the sentencing, we listened to impact statements.

Coach Henderson’s wife talked about thirty years of marriage and how she would never sit in the bleachers and watch him coach again. Tyler’s parents talked about a future that vanished in a hallway because he laughed at the wrong joke.

The prosecutor asked for the maximum. Josh’s lawyer asked for leniency because of his age, his isolation, his mental health. He was seventeen when he pulled the trigger. He’d be eighteen when he entered adult prison.

Then the judge asked Josh if he wanted to speak.

He stood up, hands shaking, and unfolded a piece of paper. His voice was quiet, a little higher than I remembered.

He apologized to the families. To us. To the community. He said he thought about what he’d done every day and he knew sorry wasn’t enough. He said he’d been in a dark place and made choices he couldn’t take back. He said he hoped one day he could do something that mattered from wherever he was.

He cried. He could barely finish.

The judge sentenced him to forty years in prison, with the possibility of parole after twenty-five.

When the deputies led him out, he glanced my way one last time and mouthed something I couldn’t understand. Then he was gone, door swinging shut behind him.

Afterward, in my dad’s car, I didn’t feel relief. Or victory. I felt… empty. Like someone had scraped out everything inside and left a shell.

Justice, people kept saying on TV. But justice doesn’t bring back a coach or a kid. It doesn’t un-send a text. It doesn’t un-crack glass.

Life kept going, somehow.

Cecilia and I kept working. “Healing isn’t forgetting,” she reminded me. “It’s learning to carry the weight without letting it crush you.”

Anne and I got closer. We’d barely known each other before that day. Now she was one of the only people who understood what it sounded like when footsteps stopped outside your classroom door and your whole world narrowed to a rattling handle.

Sometimes, after school, we’d sit in the chemistry lab with the lights on, just breathing. Navarro would grade papers, pretending not to watch us process.

Antonio started a survivors’ group that met at the community center in the same gym where we’d filled out those first intake forms. Twelve of us at first. We didn’t have a name. We weren’t a club. We just showed up and told the truth.

Some weeks we talked about that day. The sounds, the smells, the split-second decisions we second-guessed at three in the morning. Other weeks we talked about movies, college essays, prom, anything to prove to ourselves we were more than what had happened.

Six weeks after sentencing, the school dedicated a memorial garden in the courtyard. Two benches, each with an engraved plaque: COACH MICHAEL HENDERSON. TYLER JAMES MORRISON. A newly planted tree. Flowers blooming around the base. The breeze rattled the leaves while the principal talked about resilience and community and reminded us we were “stronger together,” even as some friendships around me splintered.

A few days later, Detective Morgan handed me an envelope.

“From Josh,” he said. “Came through the prison chaplain. You don’t have to read it. You don’t have to respond.”

I read it three times in my room.

He didn’t ask for forgiveness. He didn’t blame me. He wrote about therapy. About trying to understand the moments he’d let his anger turn into something else. About our treehouse. About the hoodie. About wishing he’d told someone—told me—how bad it had gotten before he made an irreversible choice.

I folded the letter and put it in the back of my desk drawer.

Not forgiven. Not forgotten. Just… there.

Senior year crept forward. Fire drills restarted eventually; the first one made half the school cry. Loud noises made me jump. A locker door slammed too hard and my heart went into overdrive.

But there were good days too.

Anne and I filled out college applications at the public library, sitting side by side with laptops open, choosing schools within an hour of each other because the idea of being alone in some strange dorm with no one who knew what we’d lived through felt unbearable.

Antonio got into a state school three hours away. We made him swear to stay in the group chat.

At our last survivors’ meeting before summer, someone suggested starting campus chapters at our colleges. We talked about giving presentations on trauma. On what helped and what didn’t. On how to recognize when someone is disappearing behind a smile and how to reach for them before they fall through the cracks.

“Turning your pain into something that helps other people is one of the most powerful forms of healing I’ve seen,” Cecilia said from the back of the room.

On the last day of school, I got there early.

The hallways were mostly empty, just a few teachers carrying boxes, the echo of footsteps against polished floors. They’d patched and painted over the bullet holes months ago, but I could still see where they’d been, ghost circles in the paint.

I walked out into the courtyard. The tree in the memorial garden had more leaves now. Flowers clustered around the benches. Someone had left a soccer ball at the base of Coach’s plaque. A folded note sat on Tyler’s, weighted with a small rock.

I didn’t read it. It was theirs.

Inside, I stopped outside the chemistry lab. The periodic table poster had been replaced with a new one: straight, bright, unwrinkled. Navarro stood at the front of the room, setting out lab sheets like it was any ordinary morning in any American high school.

It would never be ordinary again. Not for me.

I thought about all the versions of us that existed in other people’s minds now. Josh the monster. Josh the victim. Me the hero. Me the snitch. Me the idiot who said one word at lunch and never stopped paying for it in my head.

I thought about the treehouse. About spray paint on asphalt. About all the times I’d seen Josh sitting alone and told myself he was fine.

I couldn’t change any of it. I couldn’t reach back and grab his wrist that day at lunch and say, Hey, I’ve got you. Sit with us. I couldn’t un-send my messages or un-hear his list.

What I could do was this: tell the truth. Keep going to therapy. Answer honestly when reporters tried to twist the story. Show up for the survivors’ group. Start a new one in college. Check on the quiet kid in the back of the class.

I could decide, in that fluorescent-lit hallway that still smelled faintly of ammonia and pencil shavings, that one terrible day wouldn’t be the only thing that defined my life.

I could remember Josh as the boy in the treehouse and as the young man in the orange jumpsuit, and hold both of those truths at the same time without letting either one hollow me out completely.

Standing there, hand on the cool metal of the chem lab door, I chose something that felt fragile and stubborn and maybe a little bit brave.

I chose hope.

Not the loud, movie-trailer kind. The quiet, gritty American kind you only see in the aftermath—candles in paper cups, kids in folding chairs learning grounding techniques, friends holding hands as they walk back into the room where everything almost ended and say, “Okay. Let’s try this again.”

I knew the nightmares would still come. I knew there would be days the guilt would whisper that it was all my fault and I’d have to argue with it inch by inch.

But I also knew this: I survived. I told the truth. I tried to help. I was learning, slowly, to carry what happened without letting it crush me.

And somewhere, in a prison cell hours away, a boy I used to build treehouses with was writing about what he’d done, trying to understand how he became that shadow behind the glass.

Neither of us could change the past.

But maybe, just maybe, we could change what came next.