By third period, Mrs. Daniels’ voice was shaking so hard the American flag above the whiteboard trembled with it.

“If we don’t get it together,” she shouted over the chatter, “almost all of you are going to fail this term!”

No one cared.

A paper airplane skimmed past the faded poster of the Bill of Rights. Someone in the back row filmed a TikTok under the table. Two boys tried to balance pencils in their hair. Somewhere near the middle of the room, a girl in a cheer jacket practiced hand motions instead of writing notes.

“Does anyone care about anything that I am saying?” Mrs. Daniels demanded.

A beat of silence.

“I do,” a voice said.

It was soft, but the room heard it because everyone else had finally run out of jokes.

Heads turned.

The voice belonged to the smallest kid in the class—small enough that from the back row all anyone could see was a tuft of dark hair and a pair of big glasses barely visible over the edge of the desk.

Lucas.

The first day he walked into Madison Ridge Middle School—the big public school on the edge of a mid-sized American town with a football field, a marching band, and a thousand kids who all seemed to already know each other—he felt like someone had dropped him into a TV show halfway through the season.

He paused by the office, where a faded banner read WELCOME BACK, RIDGE RAMS! Below it, in tiny letters, was a list of “School Goals”: improve attendance, improve state test scores, maintain district funding.

He never would’ve guessed his name would end up tangled in those bullet points.

“Hello!” The woman at the front counter had a bright smile and a coffee mug that said WORLD’S TIRED-EST COUNSELOR. “You must be Lucas.”

“Uh, yeah,” he said, hitching his backpack higher on his shoulder.

“Come on in,” she said. “I’ll walk you to your homeroom so you don’t get lost in the jungle.”

He followed her down a hallway lined with lockers and motivational posters. Somewhere, someone’s AirPods leaked a pop song. The air smelled like floor cleaner, cafeteria food, and that faint sour note of too many teenagers in one building.

“Don’t worry,” the counselor said quietly. “Middle school is rough on everybody. You’ll find your people.”

He nodded, even though inside, his stomach was doing flips. He’d heard that line before. At his old school. And the one before that.

What he didn’t tell her was that he’d already decided not to get his hopes up.

Mrs. Daniels’ classroom had the usual American setup: whiteboard, projector, faded multiplication tables taped to the wall. A flag hung in the corner. The desks were arranged in pairs, facing the front.

Every head swiveled as Lucas stepped inside.

He was used to the pause.

He was twelve, but his body hadn’t gotten the memo. Dwarfism meant his legs were short, his arms stocky, his torso a little longer than average. At home, his parents had a step stool in every room. At school, everything felt like it had been built for giants.

“Class,” Mrs. Daniels said, smoothing her cardigan, “this is our new student, Lucas. Make him feel welcome.”

A blonde girl in the front row with a perfect high ponytail and a rhinestone cheer bow inhaled sharply. “He’s so cute,” she whispered to her friends, not nearly quietly enough. “Like a tiny puppy or a baby kangaroo.”

Her friend snorted. “Can I pick you up and put you in my pocket?”

Laughter flickered across the room like static.

Lucas forced a smile. “I’m not a puppy,” he said. “Or a baby kangaroo. I’m the same age as you.”

He dropped his backpack next to the only empty desk—back row, far right. When he sat, the desktop came up to his chest. He tried to see the board. All he saw was the back of three ponytailed heads and a tangle of shoulders.

He stretched his neck. Nothing.

“Um, Mrs. Daniels?” he said, raising his hand.

“Yes, Lucas?” she asked, grateful that at least one student was interacting with her for something other than a bathroom pass.

“I can’t… see,” he admitted. “From back here. Could I maybe swap seats with someone?”

“Of course,” she said immediately. “Tina, switch with him.”

The blonde cheerleader spun around. “But I’m sitting with my friends,” she protested. “I don’t wanna move.”

“It’s not up for discussion,” Mrs. Daniels said. “Please switch.”

Tina rolled her eyes as if the world had personally betrayed her, then stood up in a storm of perfume and glitter. As Lucas slid into her old seat near the front, she leaned over him, fake smile frozen on her face.

“You will pay for this,” she whispered.

The funny thing was, she thought she was the scary one.

That night, in a small house on a quiet American cul-de-sac where the neighbors flew flags on their porches and mowed their lawns in neat stripes, Lucas sat at the dinner table pushing peas around his plate.

“So,” his mom said, topping off his dad’s iced tea, “first day. Tell us everything.”

“Everything?” he echoed.

“That sigh says everything,” his dad muttered, glancing up from the mail. “What happened? Did someone say something?”

“Stares, snickers, rudeness,” Lucas said. “The usual.”

He poked a pea hard enough that it shot off his plate and rolled onto the placemat.

“Sometimes I wonder why you guys gave me a chance,” he blurted. “Did you even know I was… y’know. Different? When you adopted me?”

His mom’s face softened. His dad set the envelopes down.

“You really wanna know?” his mom asked.

He nodded.

She wiped her hands on a dish towel and sat down, eyes drifting, like she was rewinding an old home movie only she could see.

“The day we met you,” she said slowly, “we were so excited we could barely sign our names on the forms. But right before we saw you, the nurse pulled us aside.”

“Her name was Karen,” his dad added. “Of course it was Karen.”

“She told us you had dwarfism,” his mom went on. “That your birth mother… had decided she couldn’t handle that. She warned us you might have a hard life. Medical stuff, surgeries, stares. She said we might need more time to reconsider.”

Lucas swallowed. “Did you?”

“Not for one second,” his dad said firmly.

His mom reached across the table and took Lucas’s hand.

“When we walked into that little room,” she said, “you were swaddled up like a burrito, glaring at everyone like you were already done with the world. The second I held you, I knew. You were ours. We had so much to celebrate that day, and we still do. Your Gotcha Day is coming up, remember?”

He nodded. “I… was kinda hoping to have a real party this year,” he admitted. “Like, not just cake with you guys. A real one. With friends.”

His mom and dad exchanged a look over his head. It was quick, but he saw it—the one that said we want that for you, but we’re scared to hope too.

“Well,” his dad said, clearing his throat, “for that, we need some guest list names. So how about we figure out how to get you some friends first, huh?”

Easier said than done.

By the time the second week rolled around, Lucas had collected a growing catalogue of Madison Ridge moments:

The time a boy in P.E. asked if he needed a booster seat to see the basketball hoop.

The time someone left a step stool in front of his locker with a sticky note that said YOU’RE WELCOME.

The time a girl in the hallway pretended to trip over him and then laughed, “Oops, didn’t see you down there.”

But the worst one was the flashback that repeated in his head like a broken video.

His old school. A movie theater. Charlotte.

She’d been the first girl to really talk to him. Smart. Funny. Always had a sketchbook in hand.

“I’m so excited to see this!” she’d said, grabbing his ticket. “Can we sit in the front row so we’re close to the action?”

“I kind of prefer the back,” he’d said, heart thudding. “You know. So no one sees us.”

“Why?” she’d asked, frowning.

Before he could answer, a group of boys from their grade had walked in, soda cups in hand.

“Is Charlotte really hanging out with that leprechaun?” one of them had crowed.

Her hand had dropped his.

“No, no, no,” she’d blurted. “It’s not what it looks like. We just ran into each other.”

He’d watched her back as she hurried to sit three rows up, far enough away to pretend they weren’t together.

So when Tina threatened him on day one at Madison Ridge, part of him shrugged inside.

Same story. Different zip code.

The teachers at Madison Ridge were having their own crisis.

In the staff lounge—a beige room with a flickering fluorescent light and a perpetually empty coffee pot—Principal Carlo rubbed his temples while the math teacher, the English teacher, and the science teacher all talked over each other.

“Our aggregate GPA is so low we’re in danger of losing our funding!” the principal said. “The district is watching us.”

“We’ve tried everything,” the English teacher groaned. “More homework, more quizzes, more parent conferences. The kids won’t engage. They sleep in class. One of mine took a nap on top of his essay.”

“I’m just saying,” the science teacher huffed, “with the way scores are trending, things are not looking good.”

“So what you’re actually saying,” the math teacher cut in, “is if we don’t get the kids’ grades up, we’re all gonna be fired? I need this job to support my family. We all do.”

“We’re in the same sinking boat,” Carlo said. “And the district just poked another hole in it.”

He was only half joking.

Back in Mrs. Daniels’ classroom, probability was not going any better than anything else.

“If a bag contains ten red marbles,” she read, “eight blue marbles, and twelve green marbles, what is the probability of drawing two red marbles consecutively?”

Silence.

She scanned the room. “Felipe?”

“One out of five?” he guessed.

Mrs. Daniels closed her eyes briefly. “No, that’s not…”

A giggle rippled across the back row.

“Okay,” she said, swallowing her frustration. “Why don’t we try something different. Let’s work in pairs. Maybe that will make it easier for you people to focus.”

Desks screeched as students swiveled to face their chosen partners.

Except for Lucas.

There was a kid asleep next to him, face buried in a hoodie.

“Excuse me, Mrs. Daniels?” Lucas called.

“Yes?”

“There’s no one left for me to partner with,” he said. “I mean, Randy’s here, but…”

He glanced at the snoring lump.

“I didn’t really wanna wake him up,” Lucas admitted.

Mrs. Daniels sighed, then nodded. “Work by yourself, then, Lucas.”

He chewed his lip.

“What’s the point?” a voice mumbled next to him.

He turned.

Randy had cracked one eye open. His biology textbook lay open on his desk like a dead bird.

“My brain shuts down every time I look at these pages,” Randy said. “Cells, membranes, organelles. Why so many words?”

Lucas glanced at the board. At the tired teacher. At the time slowly ticking away.

“Okay,” he said suddenly. “Let’s make it make sense through tactile learning.”

“Through what?”

“Hands-on stuff,” Lucas said. He glanced at the abandoned apple sitting on the corner of Mrs. Daniels’ desk, the one she always brought and never ate. “Hang on.”

He walked to the front, grabbed the apple, and set it between them.

“Think of this apple as a cell,” he said. “The skin? That’s like the cell membrane. It’s the VIP bouncer. It decides what comes in and what stays out. If it’s damaged, everything leaks. Chaos.”

Randy squinted. “Okay… that actually makes sense.”

Lucas cut the apple in half with the plastic knife from his lunch. “The core is the nucleus,” he said. “It’s got the DNA. The blueprints. The brain.”

“So all the important stuff is in there,” Randy said. “Like the principal’s office of the cell.”

“Exactly,” Lucas said, surprised at the warm little spark of satisfaction in his chest. “You just did a metaphor.”

Randy chuckled. “Dude. You should be a TikTok teacher or something.”

Before Lucas could reply, a hand swooped down and snatched the apple away.

“What is this?” Mrs. Daniels demanded. “Snack time?”

“No, I was just trying to help him understand through—”

“Clearly not,” she snapped. “No food in class. And no playing cards, either, Felipe. If I see those again, they’re mine.”

Lucas sat back, cheeks burning, as the apple went into the trash.

He had no idea that half an hour later, Felipe would be in the corner store explaining the probability of winning the lottery to the cashier using the exact numbers Mrs. Daniels had been trying to drill into their heads for weeks.

Or that the cashier’s uncle was the principal.

Or that word would get back to Carlo that one kid at Madison Ridge had actually used math in real life.

“Pardon me,” Principal Carlo said the next afternoon, barging into the staff lounge with a half-eaten antacid in his hand. “My heartburn can’t take much more of this. The school’s budget is on the chopping block, and so are our jobs. We only have one hope left: exceptionally high scores on the upcoming state assessments. The question is: how?”

“More practice tests,” the science teacher said. “More drills. Stricter homework policies.”

“That hasn’t been working,” the English teacher pointed out. “Our students are disengaged.”

“Because they’re not applying themselves!” the math teacher snapped. “The answer isn’t changing methods. It’s discipline.”

Carlo rubbed his forehead. “Well, maybe that’s part of it, but—”

“I’ve got something,” Mrs. Daniels blurted, surprising herself. All three colleagues turned to look at her. “It’s called tactile learning. Hands-on stuff. One of my students—Lucas, the new kid—used playing cards to teach probability to Felipe. And the kid actually… got it. What if we try something different?”

“How different?” the math teacher asked suspiciously.

“Not anything crazy,” she said quickly. “Just… let them touch things. See things. Experience the concepts instead of just reading them.”

The room was quiet for a moment.

“We’re desperate,” Carlo said finally. “Try it in your classes. If it works, we expand. If not… we go back to praying.”

Meanwhile, cheer practice was its own ecosystem.

“You missed half the routine, Polly,” Coach barked as the squad finished running through a complicated sequence at the far end of the American gym. The basketball hoops were retracted, the bleachers empty, the word RIDGE painted in bold blue on the polished floor.

Polly, all long legs and perfect eyeliner, rolled her eyes. “Oops.”

“Maybe spend less time picking on people and more time on your grades,” Coach said. “Rumor has it you’re this close to academic probation. And if that happens, you’re off the squad. We can’t have ineligible cheerleaders.”

Tina smirked from the back row, hiding it behind her pom-poms.

“Which means someone would have to step up as the new cheer captain,” Coach added. “Wonder who could handle that responsibility?”

Tina’s smirk vanished. Pressure had a new shape now: pom-poms and GPA.

Pressure was something Lucas knew too, just in a different flavor.

His sneakers, for example.

They were thrift store specials, the soles worn thin in two spots, the logo rubbed off. They worked fine. They didn’t look fine.

“What are those?” Malcolm jeered one afternoon by the bike racks, flicking one with the tip of his own spotless white shoe. “Did your grandma pull those out of the trash for you?”

Laughter popped like grease.

Lucas bit back a retort and walked away, but later, in his bedroom, he stared at his sneakers and felt the sting all over again.

“I hate these shoes,” he muttered, tugging them off and throwing them in the corner.

“They’re not that bad,” his mom said from the doorway. “Think of them like jeans. You know, vintage. Distressed.”

He sighed. “They’re not distressed. They’re destroyed.”

“You know, if kids are picking on you, you can stand up for yourself,” she said gently. “You don’t always have to just walk away.”

He thought of Charlotte in the movie theater. Of being told cringy nicknames in the hallway. Of being laughed at for how he ate, how he walked, how he existed.

“I don’t know how,” he admitted.

If there was one person who understood how it felt to be stuck, it was Tina.

On the outside, she looked like every American teen drama’s idea of a cheer captain: glossy hair, flawless makeup, a bright uniform with MADISON RIDGE stitched over the heart.

On the inside, she was a walking checklist of stress.

Bad grades. A part-time job after school at a fast-food place off the highway, where locals bought burgers and scratch-off lottery tickets. Parents always arguing about money. A boyfriend who treated bare minimum effort like a grand romantic gesture.

And now, academic probation looming like a storm cloud over her perfectly curated Instagram feed.

“If I don’t pass biology, I get kicked off the squad,” she told her older coworker one night, sliding a tray of fries across the counter. “If I can’t cheer at the games, what’s the point of anything?”

“Sounds like you need a tutor,” the coworker said. “Or a miracle.”

The miracle turned out to be five feet tall with a backpack almost as big as he was.

His name was Lucas.

And the first time she realized who he really was, she almost choked on her own guilt.

She found him in the nurse’s office a few weeks after she’d been forced to switch seats for him.

He was sitting on the edge of the cot, wiping at his eyes with the back of his hand. The nurse was busy in the supply closet.

“Uh,” Tina said, hovering in the doorway. “Hey.”

He looked up, immediately wary. “If you came to throw another joke at me, I’m not in the mood,” he said.

“No,” she said quickly. “I… I came to say I’m sorry. For… everything.”

He stared at her, surprised.

“I heard you weren’t in class,” she said. “Someone told me you were in here. I figured that was probably my fault.”

“That’s generous,” he muttered. “Usually people just deny it.”

She swallowed. “I actually want to thank you,” she said. “For helping Bruce. My little brother.”

His eyebrows shot up. “Bruce is your brother?”

“Yeah,” she said. “He told me about this cool new friend who scared off Malcolm and got him new sneakers and helped him get an A on his book report. I knew it had to be you. You’re the only new kid we’ve got.”

Lucas looked at his hands. “He’s a great kid,” he said quietly. “It’s not his fault his sister is mean.”

“I deserve that,” she said. “Look, it’s not an excuse, but… I’ve been pretty unhappy too.”

He glanced up. “Why?”

“Pressure from everywhere,” she said in a rush, as if once she started she couldn’t stop. “Bad grades. Horrible job I can’t quit because my family needs the money. A boyfriend who cheated on me with my frenemy, who probably wants to steal my captain spot the second I get kicked off the team. If my GPA doesn’t go up, I lose cheer. And if I lose cheer, I… honestly don’t know who I am without it.”

She let out a shaky laugh. “So yeah. My life kind of sucks right now.”

He sat there for a long moment, then said, “I could tutor you.”

She blinked. “What?”

“You heard about tactile learning, right?” he said. “The shell with Mrs. Chen? The cards with Felipe? The apple with Randy? It’s not magic. Just different. I can help you see it differently too.”

“You’d do that,” she said slowly, “for me?”

“You are really a great friend,” she’d told him about Bruce.

He’d said no one had ever called him that before.

Looking at her now, at the fear under the mascara and lip gloss, he realized something else: he actually liked helping people. Even people who’d made his life harder.

“Yeah,” he said. “I’d do it. For you. For Bruce. For the school.”

Her eyes filled. “You’re a better person than I deserve.”

“Probably,” he said, managing a small smile. “But you’re stuck with me now.”

From that point on, Lucas lived a double life too.

By day, he was the kid who answered questions in class and walked carefully past the football players in the hallway.

By afternoon, he was the unofficial after-school tutor of Madison Ridge.

He sat in the library with Tina, turning the parts of a cell into a story about a busy restaurant. He showed Felipe how to visualize probability with coins, dice, and the occasional pack of gummy bears. He broke down reading comprehension for eighth graders using shells and rocks and anything else he could get his hands on.

In English, he brought a conch shell to class and passed it around as he talked about Island of the Blue Dolphins.

“Karana is stranded alone on an island,” he said, the shell cool and smooth in his palm. “She has nothing but what she can find. Look at this shell. It used to be fragile, right? Just a tiny house in the ocean. But after years of waves hammering it, it grew into something strong and unique. Even alone, it transformed. That’s Karana. You don’t need a crowd to be strong. You need resilience.”

For the first time all year, half the class actually looked interested.

“This really helped,” a girl told him on the way out. “I finally remembered a theme without Google.”

The teachers noticed.

“You’ve started some kind of revolution,” Mrs. Daniels told him one afternoon, half amused, half relieved. “The principal wants to implement your ‘tactile techniques’ for the standardized tests. If this works, you’ll be a hero.”

“A hero?” he repeated.

“Kid,” she said, “you might just save this school.”

His Gotcha Day crept closer with each flipped calendar page: a Saturday in mid-spring, when the trees outside the school unfurled fresh leaves and the American flag over the entrance snapped brighter in the wind.

His mom started talking about decorations. His dad pretended not to care, then spent an hour comparing cake flavors at the bakery downtown.

Lucas printed out a handful of cheap invitations in the library, the ink a little streaky, the fonts not quite centered.

“You’re really going to hand those out?” Bruce asked, eyes wide.

“Why not?” Lucas said, shrugging. “Worst case, no one comes and it’s just me and my parents and three hundred balloons in the living room. Best case…”

He didn’t let himself say it.

At lunch, he approached the tables that had once felt like distant planets.

“Hey,” he told Randy, sliding an invite onto the table. “I’m having a Gotcha Day party. It’s like a birthday, but for adoption. If you don’t know what it is, come find out.”

“Free food?” Randy asked.

“Probably,” Lucas said.

“I’m in,” Randy said.

He gave one to Felipe by the vending machines. One to the girl from English who’d liked the shell metaphor. One to a kid from science whose eyes always lingered on the board but whose test scores never matched the way he watched.

He even dropped one, hand shaking, on the cheer table.

“Hey,” he said, voice cracking a little, “if you guys aren’t busy that night, you could…”

He trailed off under the weight of three identical skeptical stares.

“Sure,” Tina said, rescuing him. “We’ll see.”

It was the nicest answer he’d gotten all day.

The day of the state assessments, the whole building smelled like newly sharpened pencils and anxiety.

“Just remember,” Principal Carlo told the assembled seventh graders in the gym, his voice echoing off the bleachers. “These tests matter. For you. For us. For the school. For our funding. But I believe in you. And you have an advantage this year: thanks to Lucas, you’ve got more ways to understand the questions than ever before.”

A few kids clapped. One whooped. Most just shifted their feet.

In the classrooms, teachers quietly passed out scratch paper and, where it was allowed, ordinary objects: coins, paper clips, little plastic counters.

As Lucas bent over his own test booklet, he couldn’t help picturing the web of people connected to every bubble he filled in: teachers whose jobs depended on these scores, classmates whose families were barely hanging on and couldn’t afford a school closure or rezoning, a principal who had spent too many nights staring at spreadsheets.

He pictured his parents blowing up blue and white balloons in the living room for a party that might just be the three of them.

He gripped his pencil.

And he did what he did best.

He tried.

A week later, when his mom called him to the living room the night of his Gotcha Day, the house looked like a party store had exploded.

Streamers. Balloons. A “HAPPY GOTCHA DAY” banner strung under the TV, each letter hand-drawn. A cake box on the counter.

“Hey,” she said, touching his arm. “You okay?”

He swallowed. “Yeah. I just… thought people would be here by now.”

He checked his phone again. No new notifications.

“I guess I was stupid to think anyone would actually come,” he muttered. “I should’ve told you to cancel. I just thought if I tried—”

The doorbell rang.

He froze.

“Can you get that?” his dad called from the kitchen, like it was perfectly normal for someone to show up at their door in the middle of a family pity party.

Lucas opened the door.

“Surprise!” a chorus of voices shouted.

He blinked.

Bruce was front and center, grinning, holding a lopsided gift bag. Behind him stood Tina, in jeans and a sweatshirt instead of a cheer uniform. Randy, Felipe, the girl from English, even a couple of kids Lucas only recognized from quick glances in the hall.

“You didn’t think we forgot, did you?” Bruce demanded. “You thought we’d let the coolest tutor in Madison Ridge celebrate alone?”

Lucas’s throat closed up.

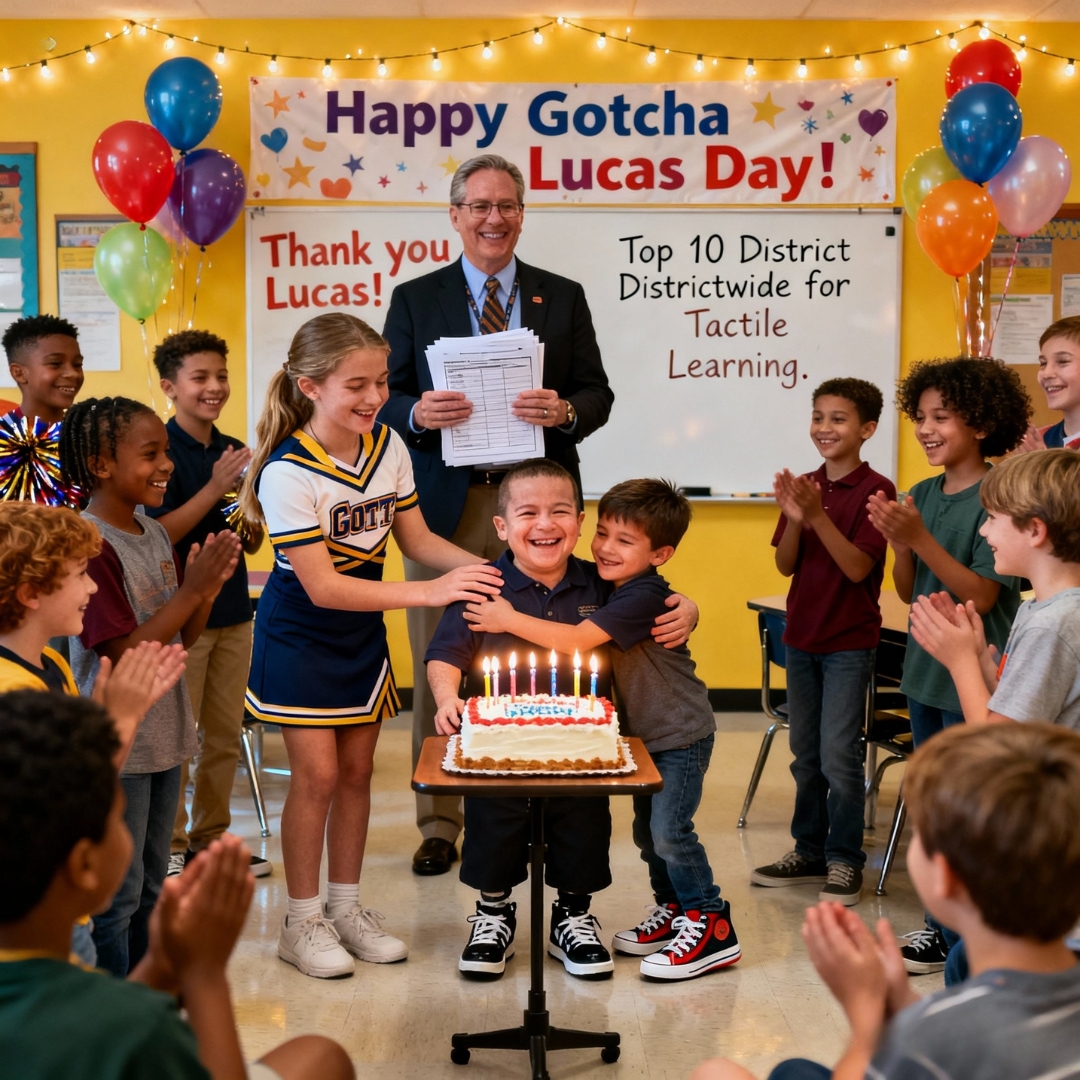

“That’s not even the best part,” Mrs. Daniels said, stepping into the doorway with Principal Carlo right behind her, both balancing trays of snacks. “We got the test scores back yesterday. Our school scored higher than it ever has in the history of Madison Ridge. We’re officially in the top ten in the district.”

“And it’s all thanks to you,” Carlo added. “You saved our funding. You saved our jobs.”

“And you saved me from getting bullied,” Bruce piped up, pointing at his new sneakers. “And you took the cheer team to the next level,” Tina said. “Because guess what? My ex-boyfriend Ben tied for the lowest test score. His answers were identical to Polly’s. They got caught cheating, and she’s off the team. We needed a new captain. Coach picked me. Her.”

She pointed at Lucas. “Okay, mostly me. But you did the hard part.”

“Now,” his mom said gently, through tears she wasn’t bothering to hide, “before we sing, go put this on.”

She handed him a small box.

Inside was a T-shirt, soft and blue, with big white letters that read: GOTCHA, WORLD. I’M LUCAS.

He laughed, choked, and pulled it over his head.

They sang. He stood behind the cake, candles flickering, the glow reflected in the shiny balloons, his parents on either side, his new friends filling the living room. Through the big front window, he could see other houses up and down the American street, porch lights that felt less lonely now.

“Don’t forget to make a wish,” his mom said.

He looked around. At the kid who used to sleep through biology now high-fiving him. At the girl who once threatened him now urging him to blow out candles faster. At the principal who’d gone from stressing about spreadsheets to laughing by the snack table.

At his parents, who had chosen him the day a nurse tried to talk them out of it.

“My wish already came true,” he said.

Then he leaned forward, took a deep breath, and blew the candles out.