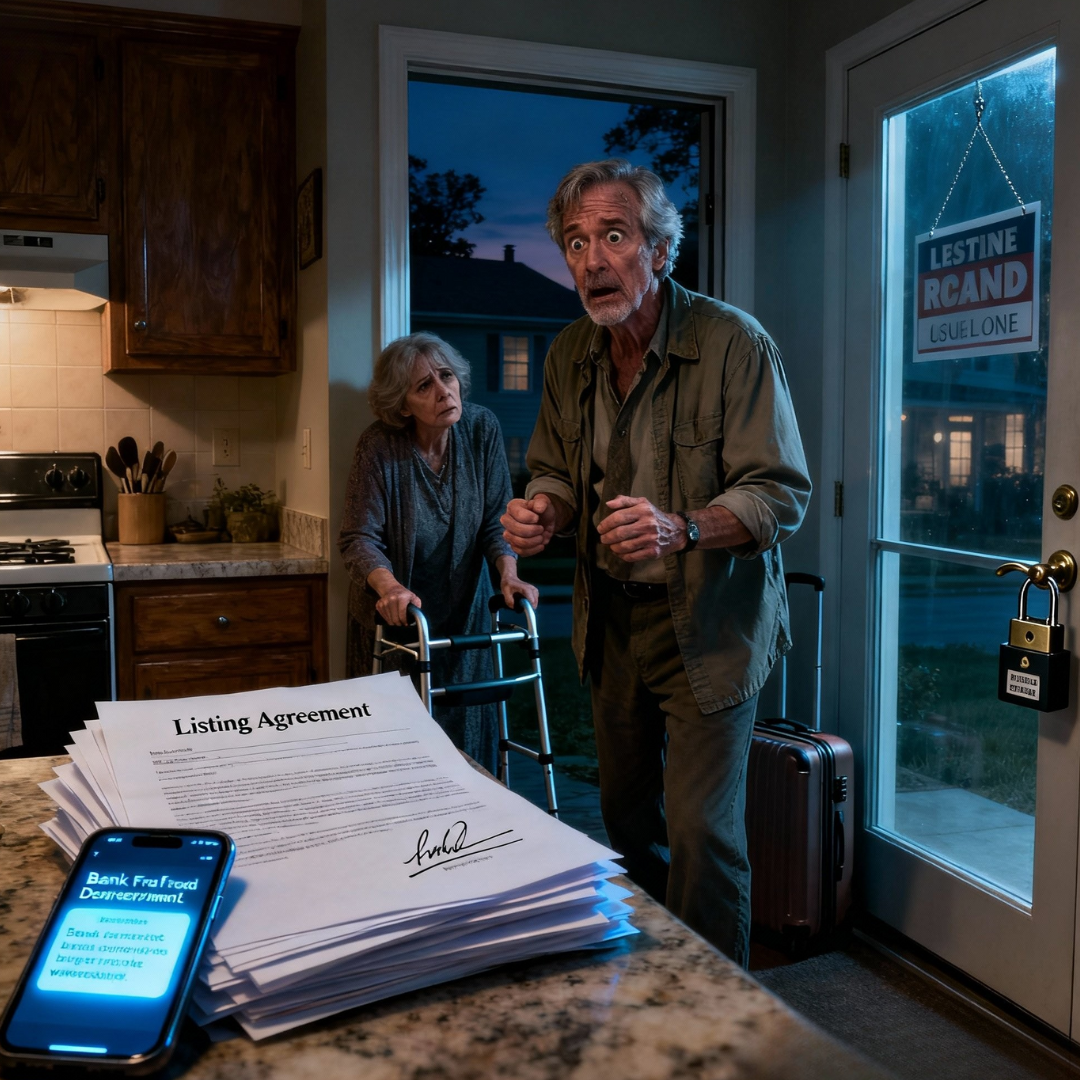

By the time I saw the lockbox hanging from my own front door in suburban New Jersey, I knew something was badly, stupidly wrong.

It was 4:47 p.m. on a Tuesday. My dashboard clock said so. The late afternoon sun washed across the quiet American cul-de-sac, kids’ bikes on lawns, flags hanging lazy on polished front porches. Our split-level house sat exactly where it always had, brick and siding warmed by October light.

But there was a realtor’s lockbox clipped to the handle.

And our living room curtains were drawn.

We don’t close those curtains during the day. Not in New Jersey. Not anywhere.

I killed the engine and just sat there for a second, hands still on the wheel, the hum of the highway still buzzing in my bones from the six-hour drive back from Pennsylvania. My wife, Helen, shifted in the passenger seat, her left leg stiff in its brace.

“Home sweet home,” she said, that weary attempt at cheer she’d been using ever since the knee replacement surgery. Then she saw where I was looking. “Robert,” she said sharply, “why is there a lockbox on our door?”

For a second, my brain tried to make it something ordinary. Maybe Marcus had called a handyman. Maybe there’d been a repair, some contractor thing.

Then I remembered: contractors don’t use realtor lockboxes.

I shoved the car door open, the cool East Coast air slapping me awake. “Stay there,” I told Helen. “Let me check.”

“Excuse me? I’ve been stuck in my sister’s guest room for two weeks. I’m not staying in the car.”

But she let me help her out anyway. She gripped her walker, testing her weight on the good leg, stubborn jaw set. This was supposed to be the good part—coming home after two long weeks in my sister Patricia’s house outside Pittsburgh. Pat had been wonderful, setting up a guest room with rails and extra pillows, making low-salt casseroles and acting like she loved every minute of playing nurse. But Helen wanted her own TV, her own coffee mug, her own too-firm mattress.

Instead, she got a lockbox and closed curtains.

I settled her on the front porch chair and turned to the door. The lockbox swung slightly when I brushed it, heavy and ugly against the familiar brass handle. Our welcome mat, the one Helen insisted on buying because it said “The Mitchells – Established 1987,” looked wrong beneath it, like the cheer had been replaced with a silent threat.

My key slid into the knob and turned halfway, then stopped. Dead resistance. The knob lock had been changed.

Whoever had done it, though, had been lazy or rushed. The deadbolt was the same. My deadbolt key turned smooth and easy with that soft, satisfying thunk I’d heard a thousand times.

The smell hit me as soon as the door swung open. Not rot or mold. Just that stale, shut-up house smell like the air had been holding its breath.

Mail was piled on the table in the entryway. Two weeks’ worth of bills and glossy supermarket flyers and a postcard from our dentist. I had specifically asked our son, Marcus, to collect our mail while we were in Pennsylvania.

He clearly hadn’t.

“Honey?” Helen’s voice floated from the porch. “What do you see?”

I took three steps into the kitchen and my stomach went cold.

On our granite counter, next to Helen’s blue ceramic cookie jar and the bowl where we kept our keys, sat a neat stack of papers. White, crisp, official. I didn’t need to read the letterhead to know what they were. I’d seen the same logo on Marcus and Amber’s closing paperwork three years earlier, when they bought their three-bedroom starter home in town.

I stepped closer. The logo confirmed it: Horizon Realty Group.

My name was on the top page.

I recognized the format from a thousand internet listings: address, square footage, lot size, features. New Jersey property details. Our kitchen, our rooms described in real estate language like they were just another asset on the market.

At the bottom of the listing agreement, in confident black ink, sat my full name.

Seller: Robert Mitchell.

Signature: Robert Mitchell.

Except it wasn’t my handwriting.

The date was five days ago.

While Helen and I had been in Pennsylvania. While she’d been sleeping in Patricia’s guest room with an ice pack on her knee and prescription bottles on the nightstand. While I’d been making her eggs in a stranger’s kitchen and watching morning shows out of New York.

“Robert?” Helen’s walker scraped over the threshold as she came inside, moving carefully, jaw tight. “What is–” She stopped when she saw my face. “What is that?”

I couldn’t answer. Because just then my phone started to ring.

Unknown number. New Jersey area code.

I almost let it go to voicemail. Something made me swipe accept.

“This is Robert,” I said.

“Mr. Mitchell?” A woman’s voice, steady but with that careful tone I’ve heard in doctors’ offices and HR meetings. “This is Amanda Chen from First National Bank’s fraud department. We’ve been trying to reach you for three days. Do you have a moment to verify some recent activity on your accounts?”

My mouth went dry. “What kind of activity?”

“Multiple large withdrawals from your retirement and savings accounts over the last two weeks,” she said. “A total of one hundred twenty-seven thousand dollars from your retirement account, and one hundred thirteen thousand from your savings. All authorized with a power of attorney on file. Given the frequency and the amounts, we wanted to confirm you approved them.”

The floor under me swayed.

“Mr. Mitchell?” her voice came again, faint around the roaring in my ears. “Are you still there?”

I stared at the listing agreement with my forged signature and tried to get my tongue to work.

“I… did not authorize any withdrawals,” I said. “My wife and I have been out of state. Someone has stolen my identity.”

“I’m very sorry to hear that,” Amanda said. Her voice shifted into a different gear—more precise, more formal. “We’ll need you to come into the branch with identification to file a formal fraud claim. Can you come tomorrow morning?”

“Yes,” I said. “Nine o’clock.”

I hung up and set the phone on the counter, my hand shaking harder than Helen’s had after surgery. Two hundred forty thousand dollars.

Our entire retirement.

“Robert?” Helen whispered. “You’re white as a sheet.”

“Marcus,” I said. The name came out before my brain had decided to say it. “Our son did this.”

My fingers were steady by the time I punched in his number. Years of engineering had taught me something about shock: once it settles, it calcifies into problem-solving.

Marcus’s phone went straight to voicemail.

“Hey, this is Marcus. Leave a message and I’ll—”

I hung up and called Amber. Straight to voicemail. I tried their house, not even sure if the landline still worked. It rang and rang, no answer.

Helen lowered herself carefully into a kitchen chair. “Robert,” she said. “Slow down. Tell me.”

I told her. About the fraud department. About the withdrawals. About the fake power of attorney.

She pressed her fingers to her mouth, eyes filling. “He wouldn’t,” she said. “He couldn’t. We paid for his college. We helped with the wedding. We… he wouldn’t.”

I wish I’d been able to agree.

Instead, I called the police.

The dispatcher was calm. “An officer will be there within the hour, sir. Please don’t confront anyone on your own.”

I thanked her, hung up, and called my sister.

“Robert,” Patricia said, picking up on the first ring. “You home? How’s Helen’s knee?”

“What exactly did Marcus say when he called you?” I asked.

She paused. “Well, hello to you, too. He called a few days after you got here. Asked how Helen was doing. He sounded concerned. Asked if you needed anything.”

“Did he ask how long we’d be there?”

“Yes,” she said slowly. “He said he’d been by your house to water the plants and grab the mail, and he wanted to know when to stop. Robert, what is this about?”

“He forged my name on real estate documents. He emptied our accounts using a fake power of attorney. Two hundred forty thousand dollars.”

Silence. Longer this time.

“That’s not possible,” she said. “Not Marcus. Are you sure?”

“I’m staring at the papers.”

She didn’t argue after that.

By the time Officer Janet Reynolds arrived, I’d stacked everything on the dining room table like evidence in a courtroom drama: the listing agreement, the seller disclosure forms, the realtor’s comparative market analysis, our last month of bank statements, a printed copy of the original power of attorney Helen and I had signed two years earlier as part of our estate planning.

Officer Reynolds looked like every small-town cop you see in American news features—early forties, hair pulled back, eyes that missed nothing. Her badge said “Middlesex County Sheriff’s Office.” Her notebook came out within seconds.

She went through everything, asking focused questions.

“Did your son have legitimate access to your house?”

“Yes,” I said. “He has a key. He knows the alarm code.”

“And this safe?” She nodded toward the open wall safe in our study. The door wasn’t damaged. The keypad lock blinked green, waiting. “Any sign it was forced?”

“No,” I said. “He has the combination. We gave it to him years ago, in case we were ever stuck somewhere and needed him to grab documents.”

“The original power of attorney was stored there?”

“Yes. It’s gone.”

She wrote that down. “And Mrs. Mitchell,” she said, turning to Helen, “where were you during this time?”

“In Pennsylvania,” Helen said. Her voice shook, but not with fear. With anger. “I had major surgery. Knee replacement. My sister took care of me. I wasn’t… helpless. I was recovering.”

“You were temporarily unable to manage your own affairs?” Officer Reynolds asked gently. “Out of state, under medication?”

“I couldn’t drive,” Helen admitted. “But I could sign my own name.”

“The power of attorney you signed,” the officer said, flipping through the copy I’d given her, “says it can be used in the event of your incapacity. Your son will likely argue this qualified.”

“It also says it can only be used in our best interests,” I said. “Health, bills, necessary expenses. Not selling our house. Not draining our accounts.”

Officer Reynolds nodded. “Mr. and Mrs. Mitchell, I won’t sugarcoat this. These cases get messy. Families, shared access, half-verbal agreements. But what I see here—this volume of money, forged signatures, a fake notarization—this is serious. We’re talking felony theft, fraud, and exploitation of older adults.”

“We are not elderly,” Helen snapped.

“In the eyes of New Jersey law,” the officer said, “over sixty is considered a protected age for financial exploitation statutes. It actually helps your case. I’ll file this as felony theft and fraud and escalate it to our detective unit. You should hear from someone within twenty-four hours.”

After she left, the house was too quiet. The refrigerator hum sounded loud. The ticking of the clock in the hallway scratched at my ears.

Helen looked at me across the table, her walker at her side like a third person in the room.

“Why?” she whispered. “We gave him everything.”

I didn’t have an answer.

My phone rang again at 6:52 p.m.

Marcus.

“Dad,” he said when I answered. “Hey, I saw I missed a few calls. Everything okay? How’s Mom? Did you get home all right?”

He sounded exactly like he always did. Like nothing was wrong. Like the world hadn’t tilted.

“Where are you?” I asked.

“At home,” he said. “Why? What’s going on?”

“I need you to come over. Now.”

A beat of silence. “Dad, it’s almost seven. Amber’s making dinner, and I’ve been at work since—”

“Now, Marcus.”

Something in my voice must have gotten through. Another pause. “Okay,” he said finally. “Twenty minutes.”

I hung up and switched my phone to audio record. I’m not proud of that. But I am a mechanical engineer. I spent forty years documenting everything. This was no different.

I also called our estate lawyer, James Morrison, and left a voicemail: “Emergency. Marcus. Call me first thing.” Then I called the realtor whose name was on the paperwork and left a message stating clearly that any listing of my property had not been authorized and must be withdrawn immediately.

Marcus walked in at 7:18 p.m., hoodie over his dress shirt, work ID still hanging from his neck. He looked tired. A little older than the last time I’d seen him. For half a second, my brain tried to pretend this was about some misplaced holiday card.

“Dad, Mom,” he said, frowning as he took in our faces. “What’s—”

I pointed to the paperwork. “Explain.”

He stepped closer, picked up the listing agreement, and even from across the table I saw the way his hand trembled.

“Where did you get this?” he asked.

“From our kitchen,” I said. “Next to a realtor’s lockbox on my front door.”

He stared at the signature. At the date. At the Horizon Realty logo.

“I was going to tell you,” he said finally.

“Tell us what?” Helen’s voice was razor sharp. “That you stole our life savings while I was learning how to climb my sister’s stairs?”

“I didn’t steal anything,” he said quickly. “Okay? I borrowed it.”

“Borrowed,” I repeated.

He ran both hands through his hair, pacing once, twice. “Look, you and Mom are fine. You have the house, you have your pensions, you’re not hurting for money. Amber and I… we’ve been struggling. Her business tanked. We had credit card debt, medical bills. Then this investment opportunity came along—crypto, high-yield trading—everyone at work was talking about it.”

Helen let out a harsh, disbelieving laugh. “Crypto.”

“It was vetted,” he insisted. “At least I thought it was. People were doubling their money in months. I figured, okay, if I pull some from your accounts, just for a bit, I can put it in, get a huge return, pay you back, and you’ll be better off. Everyone wins.”

“You thought you’d take two hundred forty thousand dollars from us without asking,” I said, “and we’d never notice?”

“I thought I’d pay it back before you needed it,” he shot back. “But then the platform froze withdrawals. They said it was a temporary halt. I panicked. I needed a way to show ‘liquidity’ so they’d let me cash out. So, yes, I talked to a realtor. I thought if we could list the house—just list it, Dad, we weren’t going to actually sell it—we’d have enough equity on paper to satisfy their requirements.”

“You forged my signature,” I said. “You created a fake power of attorney. You emptied our accounts. You changed the locks on my own front door.”

“I had to show commitment,” he said, his voice rising. “They wanted proof. I didn’t think it would go this far.”

“You had two weeks,” Helen said quietly. “Two weeks of transactions. You didn’t stop after the first one. Or the second. Or the seventh.”

Her eyes were wet now, but her voice was steady. “You looked at the numbers on those screens and kept going. That wasn’t panic, Marcus. That was choice.”

“You don’t understand,” he snapped. “Amber’s parents—”

“This isn’t about Amber’s parents,” I said. “This is about ours.”

He stared at me, breathing hard, jaw tight.

“You called the police, didn’t you?” he said. “You already did.”

“Yes.”

“Jesus,” he muttered, stepping back like I’d hit him. “You called the cops on your own son.”

“I reported a crime,” I said. “The fact that the criminal shares my DNA is your responsibility, not mine.”

His face flushed. “One mistake—”

“One mistake?” Helen’s voice cut through his. “One mistake is forgetting an anniversary. One mistake is a parking ticket. You made a hundred choices. Every signature, every click, every lie. Get out of my house, Marcus.”

“Mom—”

“Out,” she said. “Now.”

For a second, he looked like a ten-year-old caught with his hand in the cookie jar. Then his expression hardened.

“You’ll regret this,” he said to me. “When the DA’s done with me, you’ll have a son with a record and no money anyway. You’re not getting it back.”

“It’s already gone,” I said. “The rest is up to a judge.”

He slammed the door behind him.

The next day, I sat at First National Bank at 9:00 a.m. on the dot. Amanda Chen slid statements across the desk. Eight withdrawals over eleven days. Fifteen thousand. Twenty-five. Thirty-two. Forty-five. Fifty.

“The power of attorney looked legitimate at first,” she said, showing me a scanned copy. “Names, signatures, notary seal. But when our system ran the notary registration number, it came back invalid. That’s when I tried to call you.”

“Where did the money go?” I asked.

She pulled up a screen. Logo, neon-bright. “CryptoMax Premium Trading,” she read. “They advertise out of Miami and Las Vegas. Officially registered offshore.”

The website looked slick in that too-slick way, full of smiling stock-photo Americans talking about “financial freedom” and “retiring early in the USA.” Big numbers, bigger promises.

“It’s a scam,” Amanda said flatly. “We’ve seen this pattern before. Folks are shown fake dashboards with false balances to keep them sending more money. Then the site vanishes. There’s no actual trading happening. Recovering funds is extremely difficult, but we’ll file an insurance claim. It will take time. There’s no guarantee we can recover the full amount.”

I thought of Marcus’s confident face as a child, holding up his first report card. His teenage certainty that he knew everything. His adult voice telling me, “Trust me, Dad, I’ve got this.”

“Can you freeze everything else?” I asked. “Credit lines, debit cards, anything with my name on it.”

“Yes, sir,” she said. “We’ll place fraud alerts with the credit bureaus as well.”

By that afternoon, Detective Mike Sawyer had called. His voice was low and steady, a New Jersey cop voice if I’d ever heard one.

“I’ve reviewed the report,” he said. “What your son did is textbook financial exploitation. Clear pattern. Clear paper trail. Honestly, Mr. Mitchell, this is one of the clearer cases I’ve seen.”

“Then we move forward,” I said.

“I have to ask,” he said. “You’re sure? These cases blow families apart. You’re talking felony charges in a U.S. state court. Prison. A permanent record.”

“My son stole two hundred forty thousand dollars from his recovering mother and tried to sell our house out from under us,” I said. “If his last name weren’t Mitchell, you wouldn’t even be asking.”

He was quiet for a moment. “Fair enough,” he said. “I’ll send it to the county prosecutor.”

James Morrison, our lawyer, looked grim when I slid the same stack of papers across his desk.

“We can sue him civilly,” James said. “We should. We can try to claw back anything he has—house, car, retirement accounts. But if he’s already dumped everything into this… CryptoMax thing, we may be chasing ghosts.”

“We’re not just doing this for the money,” Helen said. “We’re doing it because what he did was wrong.”

James nodded. “Then prepare yourselves. It’s going to get ugly.”

The DA’s office moved faster than I expected. Maybe because it made good headlines in American media: “Local Man Accused of Exploiting Parents, Draining Retirement for Crypto Scam.” They filed six felony counts: theft, identity theft, forgery, fraud, financial exploitation.

Marcus was arrested at his tech company in downtown Newark. I saw it on the local news that night—our own son’s mugshot on a flat-screen TV in our new, smaller living room. He looked stunned. Not remorseful. Stunned.

His bail was set at seventy-five thousand dollars. Amber’s parents posted it.

She showed up at our door two days later.

“Mr. Mitchell,” she said, eyes red, hair scraped into a messy bun, New Jersey sweatshirt hanging off one shoulder. She looked younger than her thirty-two years, like the life had been scraped out of her. “Please. Can I talk to you?”

Helen stayed in the bedroom. She’d said she couldn’t look at Amber without seeing Marcus’s face.

Amber sat on the edge of our sofa, twisting her wedding ring.

“I didn’t know,” she said. “I swear I didn’t know he was using your accounts. He told me the crypto money was his. He said he’d been saving. When you called the police, I thought you were overreacting. Then the detective came with a search warrant. They took his laptop. I saw everything.”

Her voice broke. “The fake power of attorney. The listing agreement. The lists of people he’d convinced to ‘invest’ with him. I feel sick. My parents… they always pushed him, you know that. The big house, the prestige. I pushed him too. But I never, ever imagined he’d do this to you.”

“What do you want?” I asked.

“To help,” she said. “To fix whatever I can. I’ve moved out. I’m filing for divorce. I’m twelve weeks pregnant, Mr. Mitchell. I can’t raise a child with someone who would do this to his own parents.”

Pregnant.

The word snapped the air out of my lungs.

A grandchild. In New Jersey. One we’d pictured taking to American ball games, teaching to ride a bike, spoiling with Christmas presents. Now tied forever to a man in a jumpsuit and a case number.

“I’ll testify,” Amber said. “I’ll give the DA everything I found. I know it doesn’t fix anything. But it’s something.”

It was.

The plea deal came a month later. Marcus’s lawyer offered: plead guilty to two felonies, accept probation and community service, agree to full restitution. No prison time if he followed all the rules.

The prosecutor laid it out bluntly. “If we go to trial,” she said, “there’s always a chance a jury sympathizes. He’s a local boy, first-time offender, pressure from in-laws, financial stress—you’d be amazed what some juries decide. With this deal, he’s a convicted felon for life, with restitution orders that follow him.”

“What would you do if it were your son?” I asked.

She looked me in the eye. “I’d want certainty,” she said. “But I’m not you. And he’s not my son.”

We went home and sat at the kitchen table, the same table where we’d paid his tuition bills.

“I want them to hear it,” Helen said finally. “The jury. The judge. I want them to hear what he did and say out loud that it was wrong. Not just paperwork wrong. Human wrong.”

So we rejected the deal.

The trial in county court felt like something out of a courtroom drama filmed for American TV, except there were no glamorous lawyers and no snappy one-liners. Just fluorescent lights, stiff benches, and people in suits lining up for coffee from a vending machine.

I took the stand first. Then Helen. Then Amanda from the bank. Then Officer Reynolds. Then Detective Sawyer. Each of us laid a brick of truth in a wall Marcus couldn’t climb over.

His defense attorney tried everything. Suggested we’d always helped Marcus financially, so he misunderstood the boundaries. Suggested I’d told him, drunk at a family barbecue once, “All this will be yours someday.” Suggested Helen’s pain meds had made her confused.

“I had a knee operation,” Helen said from the witness stand, glaring at him. “Not a brain transplant.”

The jury took four hours.

Guilty. On all six counts.

At sentencing, the judge looked at Marcus for a long time.

“You had options,” she said. “This is the United States. Help exists for people in debt. You could have asked your parents for a loan. You could have taken on extra work. You could have downsized your lifestyle. Instead, you chose the most selfish path available to you. You lied, you forged, you exploited. And you did it while your mother was recovering from major surgery out of state. The law requires me to consider many factors. But in plain language, Mr. Mitchell, what you did was cruel.”

She sentenced him to eight years in state prison. Full restitution. Long-term no-contact order unless we initiated it.

Eight years.

He’ll be forty-three when he gets out.

The civil suit James filed marched along in its own slow American way. We went after Marcus’s house. His half of it, anyway. Amber had already divorced him, but she cooperated. The house sold, the bank got its share, and we got forty thousand. His 401(k) was liquidated—another twenty-eight. His car went back to the lender.

When the dust settled, before the bank’s fraud insurance kicked in, we’d recovered ninety-five thousand. The bank eventually reimbursed eighty more through their coverage.

We were still sixty-five thousand short.

We sold our big house. Patricia and Helen’s parents insisted on helping. We bought a smaller condo closer to downtown, near the train line. I went back to work part-time as a consultant, helping a local manufacturing firm in New Jersey update their systems. Helen did books for a dentist’s office three mornings a week. It wasn’t how we pictured our American retirement, but the bills got paid.

Sophie was born in May.

Amber sent one photo first: a tiny baby with a shock of dark hair, a wrinkled face, a hospital blanket. Underneath it, a note.

I know this is complicated. I know you’re hurting. But this is your granddaughter. She’s innocent. If you ever want to meet her, I’d like that. No pressure. – Amber

Helen cried at the kitchen table for two full days. On the third, she picked up the phone.

“Amber,” she said. “When can we see her?”

The first time I held Sophie, in Amber’s small rental duplex with a view of the highway instead of a yard, she wrapped her tiny hand around my finger. Her eyes—Marcus’s eyes, Helen’s eyes, some American blend of all of us—blinked up at me.

She didn’t know anything about crypto or courtrooms or prison jumpsuits. She knew warmth, a heartbeat, the sound of Helen’s voice singing softly.

“I’m not asking you to forgive him,” Amber said quietly, watching us. “I don’t know if I ever will. But she deserves grandparents.”

We see Sophie once a month now. We go to parks with American flags on the little city hall. We watch her toddle toward ducks and climb plastic slides. Sometimes she points at photos on Amber’s wall and says, “Mommy. Nana. Papa.” When she points to Marcus’s face, Amber just says, “That’s your dad,” and changes the subject.

He writes from prison sometimes. The envelopes come with Department of Corrections stamps, the return address a number instead of a street. I don’t open them. Helen does. She reads them in the bedroom, quietly. Sometimes she cries. Sometimes she comes out with red eyes and says nothing.

“Do you think we did the right thing?” she asked me one night, long after she’d healed enough from surgery to walk the neighborhood on her own.

“I think we did the necessary thing,” I said. “The legal thing. The self-respect thing.”

“That’s not the same as right,” she said.

I thought about that. About the balance between justice and mercy, between love and accountability, in a country that tells you family is everything but doesn’t always tell you what to do when family is the one holding the knife.

“He chose,” I said finally. “We chose, too. To protect ourselves. To draw a line. To tell the state of New Jersey and anyone else watching that what he did wasn’t just a ‘family dispute.’ It was a crime.”

She nodded slowly. “I still feel like I failed him,” she whispered. “Like we should have seen it coming.”

“Maybe,” I said. “Or maybe he failed himself.”

Two years in, we’ve recovered about one hundred thirty thousand of what we lost, between restitution and insurance. The rest will trickle in—twenty-five percent of his wages once he’s out and working again. If he finds work. If he doesn’t run.

Sophie learned to say “Papa” last month. She ran across Amber’s living room on unsteady legs, flung herself against my knees, and laughed. I picked her up, and for a moment the weight in my chest eased.

Someday she’ll ask where her dad is. Someday she’ll ask why.

I don’t know yet what we’ll say.

I do know this: Family does not give you the right to destroy people. Love does not mean ignoring harm. Sometimes the hardest, most American thing you’ll ever do is look at your own child and say, “Enough.”

Would I do it differently if I could go back? Some days, when the condo is too quiet and I see Marcus at eight years old in my mind, grinning with a missing tooth, I think yes. Some days, when I open another bank letter or look at Helen’s tight mouth when she opens a prison envelope, I think no.

Most days, I just try to keep moving forward.

We came home from Pennsylvania expecting dust on the shelves and mail on the table. Normal life. Instead, we walked into a crime scene that didn’t look like a crime scene: no broken glass, no missing TV, just a lockbox on the door and numbers on a bank statement that said our trust had been cashed in.

We couldn’t change that.

But we could decide what happened next.

Marcus made his choice. We made ours. Now we all live with the consequences.

Eight years is a long time. Long enough for Sophie to grow from a baby into a girl with questions. Long enough for two people in their sixties to rebuild something that looks like a future. Maybe long enough for a man in a New Jersey prison to look at himself and decide to be different.

I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to look at my son and see only the boy he was, not the man he became. I don’t know if that kind of healing is possible in this lifetime.

But I know this much: we are not destroyed.

Bruised, smaller, a little poorer, a lot older, but not destroyed.

And in a country where people lose everything every day to scams, greed, and bad choices, sometimes that’s the closest thing to victory you get.