The first time my son’s fiancée saw my face, she laughed and said I didn’t need a mask for Halloween.

Twenty-five years earlier, I’d carried her out of a burning house in Portland, Oregon.

I didn’t know that part yet, of course. Back then, all I knew was that my roast was perfect, my shirt was ironed, and I was more nervous than a grown man should be about one dinner.

I’d spent the afternoon polishing the old mahogany table in my southeast Portland dining room, the same one my late wife, Marie, had loved. The house smelled like roast beef, garlic, and rosemary. Potatoes crisping in the oven, green beans cooling in my mother’s chipped serving bowl. After sixty-two years on this planet and thirty of them as a firefighter, I’d learned that you can’t control much in life, but you can control dinner.

My son Gordon had sounded seventeen when he called, even though he was thirty-four and divorced.

“Dad, you’re gonna love her,” he said. “Her name’s Pearl. She’s funny, sharp, works in design. She’s not like… you know. Before.”

His last “before” was a messy divorce and an apartment that looked like it had been hit by a storm. I’d listened to him fall apart over the phone while sitting alone in this house Marie and I bought back when gas was cheap and we still went to Blazers games in the cheap seats. When he said he’d met someone who made him excited again, I wanted it to be true.

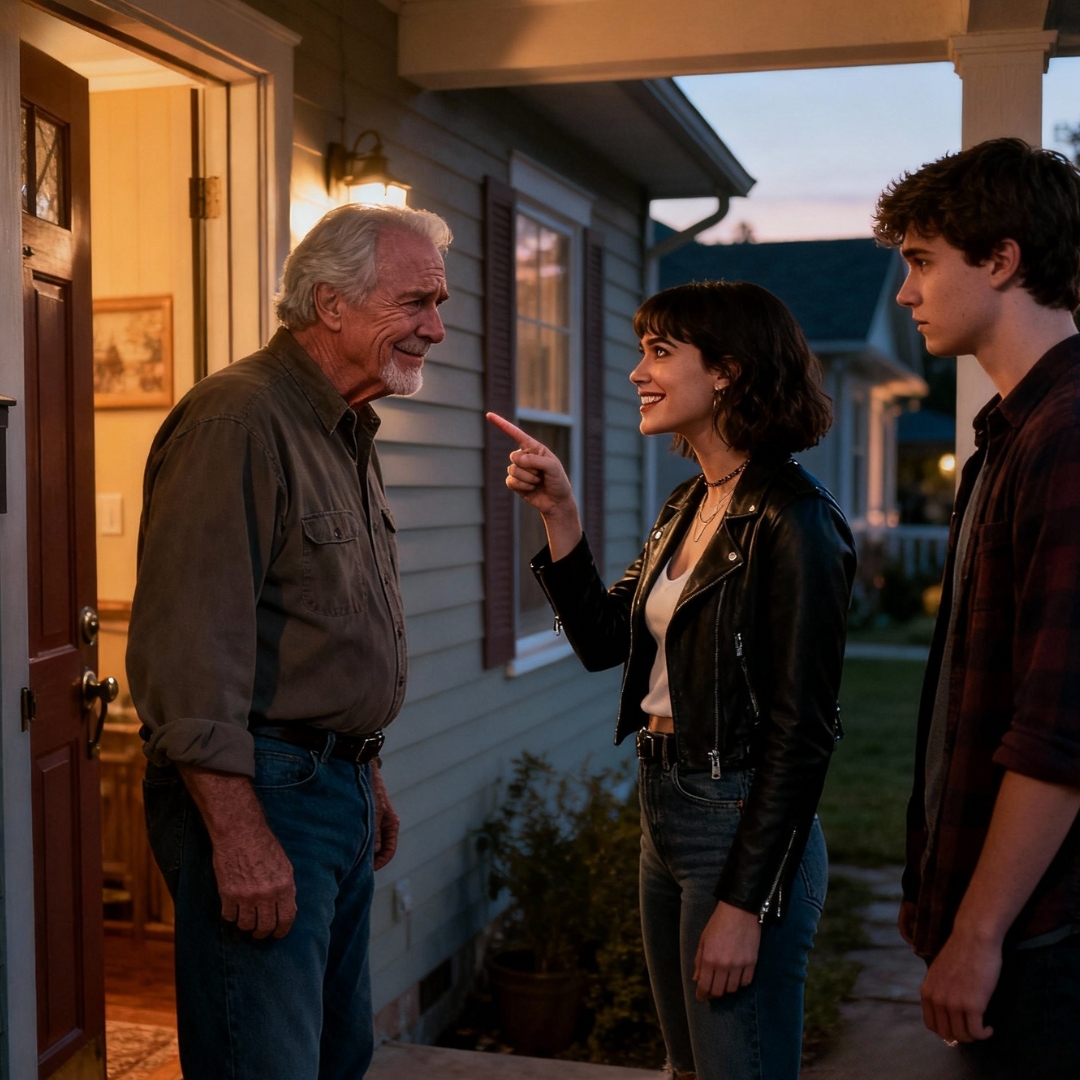

The doorbell rang at six on the dot.

I wiped my hands on a towel, took a breath, and opened the door with what I hoped was a friendly, father-of-the-groom kind of smile.

She saw my face and burst out laughing.

“Oh,” she said, eyes flicking over my scars like they were a joke waiting to be told. “At least you don’t need a mask for Halloween. You’re scary enough as it is.”

It was so fast I almost thought I’d misheard her. Gordon didn’t correct her. He let out this weird, nervous chuckle, like he wasn’t sure which side to stand on.

My smile froze. The March air felt suddenly colder.

“Come in,” I said. “Dinner’s ready.”

Pearl stepped past me like she owned the place already. Blonde hair in a sleek ponytail, expensive boots, clothes that said downtown Portland boutique rather than Fred Meyer sale rack. Her perfume filled the hallway, floral and sharp.

She did a quick scan of the entryway. Her fingers ran over the old oak trim like she was appraising it.

“Gordon says you’ve lived here forever,” she said, glancing toward the living room, where my thrift-store lamp and Marie’s faded floral couch sat in their usual spots. “The furniture certainly proves it. Do you ever think about updating?”

“I like my home the way it is,” I replied, carrying the roast into the dining room.

“Of course you do,” she said, the corners of her mouth curling up in a smile that didn’t touch her eyes.

Gordon cleared his throat and tried to rescue it. “Dad’s sentimental,” he said, taking his seat. “This house is kind of a museum of my childhood.”

“Mm,” Pearl said, sliding into the chair beside him. “A museum is one word for it.”

I carved the meat and set generous slices on their plates. Before I’d even finished, she pushed hers a few inches away, like she didn’t want the juice near her.

“So, Clarence,” she said, picking up her fork by the very end, like it might bite her. “You’re retired now, right? What do you do with all your time?”

“I stay busy,” I said.

“I’m sure,” she replied in a tone that said she wasn’t sure at all. “Must be lonely in such a big house. Do you ever think about downsizing? This place must cost a fortune in Portland taxes.”

“The house is paid off,” I said. “The expenses are manageable.”

She touched Gordon’s arm, a casual, possessive brush. “Still, four bedrooms just sitting here. Gordon and I were talking about how silly it is to keep so much unused space.”

There it was. The shift. The way her eyes had swept the house when she walked in hadn’t been curiosity. It had been inventory.

“This is my home,” I said quietly.

“For now,” she replied, that bright smile widening.

We finished the meal with my jaw clenched so tight my teeth hurt. Every other sentence out of her mouth was a critique disguised as a joke: the old wallpaper, the “vintage” dishes, the street having “so much… character.” Gordon kept laughing along, the way you do when you want everyone to get along and you’re too scared to tell your partner she’s being rude.

When she finally set down her fork and said, “Gordon and I were thinking, after the wedding, it makes perfect sense for us to move in here,” something in me went very still.

“Thank you both for coming,” I said, standing so abruptly my chair scraped the floor. “I think we’re done for tonight.”

“Dad,” Gordon protested. “We just got here.”

“I said we’re done.”

For a second I saw Pearl’s real face. The smile dropped. Her eyes narrowed, calculating, then she smoothed it over again like fresh paint.

“Well,” she said, rising slowly, “I suppose we know where we stand.”

At the door, Gordon hesitated. “You embarrassed us tonight,” he said, low. “She was trying. You’re being sensitive.”

“Good night, Gordon,” I said, and closed the door behind them.

I cleaned up in silence. Pearl’s plate was still almost full. I scraped her untouched dinner into the trash, washed the dishes one by one, dried them, put them back in their places. By the time I turned off the kitchen light, the roast was cold and my anger had cooled into something harder.

Pearl didn’t see me as a person. She saw a house with no mortgage and a retired man with no one else living in it.

The next morning, my phone rang at 8:30. Gordon.

“You owe Pearl an apology,” he said as soon as I answered. “She was just joking. You made things really awkward.”

“My problem,” I said, “is being insulted in my own home.”

“You’re too sensitive. She’s trying to connect with you. We’re planning a life together. Can’t you just… not make this hard?”

“No,” I said simply.

“Fine,” he snapped. “Don’t expect to hear from us for a while.”

He hung up.

I set the phone down and stared at my coffee. The house felt suddenly larger, every creak and drip louder. Years ago, when Marie died, I’d thought grief was the worst silence in the world. This felt different. Not grief. Not yet. Something more like a warning siren in my chest.

That night, instead of watching the Blazers lose by ten again, I sat at my old desktop computer and looked up Oregon inheritance laws. It wasn’t exactly light reading, but thirty years in the Portland Fire Bureau had taught me how to absorb procedures and rules when lives depended on it. This time, it was my life’s work on the table.

I read about wills, revocable trusts, transfer-on-death deeds, how in Oregon you could leave your property to whoever you wanted as long as you were of sound mind and you documented it correctly. I took notes in my blocky handwriting: CHARITY OPTION. PROTECT HOME. NO RIGHTS FOR SPOUSE IF NOT ON TITLE.

Gordon called again a week later, voice buzzing with excitement.

“Dad, great news,” he said. “Pearl and I are engaged. Wedding in July. And we’ve been talking about logistics. Your house makes perfect sense for us.”

“What logistics?” I asked, though I already knew.

“You’re alone, you’ve got four bedrooms just sitting there. We’d help with utilities, fix the place up. Pearl’s already looking at paint colors for the guest rooms.”

“Those aren’t guest rooms,” I said. “They’re my rooms. And you won’t be moving in.”

A beat of stunned silence.

“You can’t be serious,” he said. “This is what families do. We take care of each other.”

“I am taking care of someone,” I replied. “Me.”

He started to say something else, but I hung up. My hands were shaking a little, but not from fear. From clarity.

The next day, I called a mobile notary service and then, on their recommendation, an estate lawyer. They sent out a notary first—a woman in her forties with a leather briefcase and an efficient air. We sat at the same dining table where Pearl had mocked my wallpaper, and I signed papers that changed the future.

The house that had held my entire adult life—Marie’s laughter, Gordon’s first steps, a thousand quiet dinners—would go to the Portland Firefighters Benevolent Fund when I died. My bank accounts would be split between a scholarship for children of fallen firefighters and a small sum for Gordon, locked up in such a way that no one could bully it out of him.

The notary watched each signature, stamped and sealed every page.

“Once these are recorded,” she said, “it doesn’t matter who expects what. The law will follow what’s written here.”

Two days later, Gordon knocked on my door with a strained smile and a very clear agenda.

“We need fifteen thousand dollars,” he said after five minutes of small talk he clearly didn’t care about. “Venues in Portland aren’t cheap, and Pearl deserves something nice. We’ll pay you back after we sell your place and move somewhere bigger.”

I almost laughed.

“No,” I said.

“You could take a home equity loan,” he argued. “You’re sitting on a half-million-dollar asset, Dad. What are you saving it for?”

“For me,” I said. “For causes I’ve chosen. Not for your wedding.”

That was the moment his face changed. His frustration hardened into something else.

“This is exactly what Pearl said,” he muttered. “You care more about your house than your family.”

“She’s wrong,” I said. “I care about boundaries. That house is the reason you had food, clothes, and braces growing up. I crawled through smoke for thirty years so I could pay it off. I’m not handing it over to impress your fiancée’s Instagram followers.”

He left angry. I watched from the window as he walked to his car, phone in his hand. When he leaned against the driver’s door and put it on speaker, I saw Pearl’s face flash on the screen—tiny, angry, listening.

The next phase of her campaign started a week later.

She called, voice soft, all edges polished away. “Clarence, I owe you an apology,” she said. “I was nervous that night. I tried too hard to be funny and came off rude. Can we start over? Let me make dinner for you this time?”

Her tone was so different that if I hadn’t seen that first look on my porch, I might have believed it. As it was, I agreed—with conditions. Neutral restaurants, short visits, never with paperwork on my table.

She played the part well. At a downtown diner, she listened to my stories about the firehouse with wide eyes. She asked about Marie. She even teared up when I mentioned the night we found out about the cancer.

“For what it’s worth,” she said, reaching across the table to touch my hand lightly, “I’m really glad Gordon has you.”

She started dropping by the house with Gordon, always with something in her hands. Groceries I didn’t need—organic vegetables, imported olive oil, artisan bread. She made a big show of paying for lunch and leaving generous tips. She complimented the old woodwork she’d mocked before.

“This kitchen has such great bones,” she said one afternoon, running her hand over the worn cabinets. “You just don’t see craftsmanship like this anymore.”

For a moment, I almost let myself relax. Almost.

Then I found the catalogs.

After one of their visits, when the house finally went quiet, I noticed a neat stack of glossy magazines on the coffee table: West Elm, Restoration Hardware, Pottery Barn. Each one bristled with sticky notes in a tidy, looping hand.

Master bedroom – lighter colors, big upholstered headboard.

Living room – modern sofa, rip out that wallpaper.

Guest room – office/guest combo, Murphy bed.

She’d even written the room names: “Clarence’s room,” “front bedroom,” “back bedroom with small window.” My rooms. My house. Her handwriting.

The old firefighter in me—the one who’d learned to read smoke patterns and see danger where everyone else saw nothing—woke up fully.

The next week, she brought them up herself, floating it like harmless dreaming.

“Don’t you ever imagine what you’d change if money were no object?” she asked, flipping through one of the catalogs. “Like, if we ended up here someday—”

“You left these,” I said, tapping the sticky note that said master bedroom.

She went very still. For a second, something sharp flashed in her eyes, then the sweetness was back.

“Oh, those? Just silly daydreams. I write in catalogs everywhere. Gordon teases me for it.”

“He didn’t leave these,” I said. “You did.”

Her smile didn’t move, but the temperature in the room dropped ten degrees.

A few days later, the mail brought the thing that blew the whole polite façade apart: a thick envelope from a realty group on the east side.

“Thank you for your interest in our property evaluation services,” the letter inside began. “Per your request through Ms. Pearl Morrison, we have prepared a preliminary market analysis for the property at…”

I read it twice. An estimate of my home’s value. A note about “exploring listing options within the next twelve months.” The date stamped on the letter was right in the middle of her apology tour, when she’d been bringing me groceries and asking about my health.

I called the number on the letter.

“I’m the owner of that house,” I said. “I didn’t request an appraisal.”

The woman on the other end sounded startled. “Oh. Our agent took the request from Ms. Morrison. She said she was coordinating for family estate planning.”

“Email me every document you have regarding this,” I said. “And mark that request as unauthorized.”

I hung up, stared at the letter, and felt my anger settle into something like steel.

The next morning, I sat in a walnut-paneled office overlooking the Willamette River with a lawyer named Rebecca Chen. She listened as I laid it all out: the insult, the property pressure, the money request, the catalogs, the appraisal. Her pen moved quickly, notes in precise lines.

“What you’re describing,” she said finally, “is a textbook setup for financial exploitation of an elder, even if you’re not actually dependent on anyone. The good news is, you came in before any damage was done. The better news is, Oregon gives you a lot of power to lock this down.”

For an hour, we built walls on paper. An irrevocable trust putting my house beyond any spouse’s automatic reach. A transfer-on-death deed to the firefighters’ fund. Letters explicitly stating that Gordon had no expectation of inheriting the property. Notarized statements affirming my mental competence.

“Once this is filed,” Ms. Chen said, sliding the documents back to me in a leather folder, “no one can claim you were pressured later. You’ve made your choices. The law will back you.”

When I walked out of that building, the river glinting under the Portland sun, I felt lighter than I had in months. Not because I’d cut my son out of everything—he still had a modest inheritance in other accounts—but because the thing Pearl wanted most was no longer available.

A week later, Gordon called again.

“Pearl feels terrible,” he said. “She thinks you hate her. She wants to have one more dinner. Her parents will be there. Please, Dad. Let them see who you really are.”

I almost said no. Then I thought of his face on my porch, caught between the woman he loved and the father who’d raised him. One dinner wouldn’t change my paperwork. But it might change the story he was being told about me.

“All right,” I said. “My house. Saturday at six. After that, we’ll all know where we stand.”

I cleaned like it was Thanksgiving. Windows washed, floor mopped, yard trimmed. If this was going to be a showdown, I wasn’t giving anyone an excuse to call me a crank in a crumbling place. The house shone. The roast chicken came out golden. The good dishes went on the table.

They arrived twenty minutes early.

Gordon had a bottle of wine in his hand and anxiety all over his face. Pearl wore a pale dress that made her look softer, more innocent. Her smile lit up as soon as I opened the door.

“Clarence, everything smells amazing,” she said. “You really went to so much trouble.”

“Come in,” I said.

We were in the kitchen, transferring dishes when Gordon’s phone buzzed. He grimaced.

“Work,” he said. “If I don’t take this, the whole shift falls apart. Two minutes, I swear.”

He stepped out onto the back porch, pulling the door shut behind him. I could see him through the glass, pacing, gesturing with one hand.

The kitchen felt suddenly very quiet.

Pearl set down the serving spoon. Her face changed like someone had flipped a switch. The warmth vanished. Her eyes went flat and cold.

“You know you already lost, right?” she said softly.

I looked at her. “Is that so?”

“Gordon does what I say,” she hissed. “He believes you’re stubborn and selfish. You can sign all the papers you want. People get confused. Papers can be challenged. I have time. You don’t.”

I folded the towel on the counter, keeping my voice level. “I’m not afraid of you, Pearl.”

“You should be.” She leaned toward me, lowering her voice. “I grew up learning the hard way that if you don’t take what you want, someone else will take it from you. I’m not going back to living small. This house, your money, your pension—it’s just a matter of when, not if.”

“You’re wrong,” I said quietly.

She gave a little laugh. “You’re alone in a big old house in Portland. You think some charity cares about you more than your own family? You think anyone’s going to thank you for locking us out?”

The doorbell rang. She straightened so fast it made my head spin. In one breath, her posture softened, her voice lifted, and the charming fiancée was back.

“I’ll set the salad on the table,” she chirped. “This means so much to us, Clarence.”

She glided away, leaving the echo of her threat hanging in the steam from the roasting pan.

I wiped my hands, walked down the hall, and opened the front door.

A couple stood on my porch. They looked like any set of parents you’d see in a Safeway line in Oregon—late fifties, early sixties, dressed nicely but not showy. The man’s hair was mostly gray, the woman’s dark hair pulled back in a clip, silver at the temples.

“Mr. Phillips?” the man asked, smiling. “I’m Thomas. This is my wife, Donna. We’re Pearl’s parents. Thank you for having us.”

“You’re welcome,” I said. “Come—”

Thomas’s smile faltered. He looked closer, really looked at my face. His hand shot out and gripped his wife’s arm.

“Donna,” he said, voice suddenly thin. “Look at him. Really look.”

She turned to me fully. Her eyes widened. Her hand flew to her mouth.

“Oh my goodness,” she whispered. “Tom… is it…?”

“It’s him,” Thomas said. His eyes were shining now. “It has to be. That night. The fire. In Portland. September 2000. It’s you, isn’t it?”

I blinked. “I’m sorry?”

“You were a firefighter,” he said. “East side. Our house on Prescott. Electrical fire. You went in when the captain said not to. You carried our little girl out.”

I felt like someone had opened a door in the back of my mind and let in a rush of smoke. The memory came back in a single sharp image: a two-story house, flames licking out of a front window, a screaming father, a mother sobbing, “She’s still inside!” And me, young and stupid and determined, ignoring protocol because a seven-year-old was upstairs in a bedroom closet.

I staggered back a half step.

Gordon appeared behind me. “Dad? What’s going on?”

Donna was crying openly now. “We’ve looked for you for years,” she said. “We never forgot your face. You carried our daughter out like she was the most precious thing in the world. You saved her life.”

“Your daughter,” I said slowly. “Pearl.”

“She was seven,” Thomas said. “Burns on her back and arms. Terrified of fire for years. You gave her twenty-five more years she wouldn’t have had. You gave us our child back.”

Behind us, in the hallway, I heard a soft sound. Pearl stood frozen just past the dining room entrance, one hand on the wall. All the color had drained from her face.

“The man who saved me,” she whispered. “It was you.”

She took a few steps into the light, staring at me like she was seeing a ghost. One hand crept up to her shoulder blade, pressing over the spot where I knew, without seeing, scars still rested beneath her clothes.

Then, like someone had cut her strings, she dropped to her knees.

“What have I done?” she choked out, burying her face in her hands. “What have I done?”

The living room went quiet except for her sobbing. Thomas and Donna looked from her to me, confused and horrified, trying to piece together what had happened between their grateful memory and their daughter’s collapse on my floor.

“She didn’t know who I was,” I said, my voice sounding strange in my own ears. “Not until now.”

“Know what?” Donna asked, voice shaking.

“That the man she’s been insulting and trying to push out of his house is the same one who carried her out of a fire,” I said. “The one whose face she told didn’t need a Halloween mask.”

Donna gasped. Thomas swore softly under his breath—nothing harsh, just the sound of a man who’d been sucker-punched.

Pearl lifted her head. Her mascara was a mess, streaks down her cheeks, eyes wide and naked in a way I hadn’t thought she was capable of.

“I didn’t know,” she sobbed. “I swear to you, I didn’t know. I barely remember that night, just smoke and fear and strong arms. I spent my whole life trying to pretend it didn’t happen.”

Thomas looked at her, then at me. “Pearl,” he said slowly, “what have you done?”

She tried to speak and broke off, breath hitching. Gordon moved to her side automatically, his instinct to comfort stronger than his confusion. He put a hand on her back; she flinched but didn’t pull away.

I took a breath, the kind I used to take before stepping into a building that might come down on my head.

“Let’s sit down,” I said. “We can’t do this in the hallway.”

We ended up at the dining table, food cooling on the sideboard, place settings neat and untouched. Thomas and Donna sat side by side. Pearl slumped across from them, hands twisted in her lap. Gordon looked like he’d been dropped into someone else’s life.

Thomas and Donna told the story of that night again in more detail, filling in gaps my memory had left hazy. The smoke alarm at two in the morning. Flames already eating the kitchen. Running outside and realizing their daughter wasn’t with them. The captain trying to hold me back. The moment I came out of the house carrying a limp, soot-covered child.

“You disappeared after the ambulance took her,” Donna said, tears streaming down her face even now. “We wanted to thank you, but everything was chaos. We moved to Seattle a few weeks later because she couldn’t sleep in that house. We never forgot you. I saw your face in my mind every day.”

Pearl was staring at the table.

“Pearl,” I said, “look at me.”

She forced her eyes up.

“I want to understand something,” I said. “Why did you become this person? The one who walked into my home and treated me like a problem to solve?”

She swallowed hard. When she spoke, her voice was small, nothing like the bright, confident tone she usually wore.

“I hated feeling weak,” she said. “The fire, the scars… everyone always looking at me with pity. I decided I’d never let anyone see me that vulnerable again. So I made myself… hard. Untouchable. If I judged first, no one could judge me. If I took what I wanted, no one could take it from me.”

“And in protecting yourself,” I said quietly, “you learned how to hurt other people.”

“Yes.” The word came out on a sob. “I became everything I should have despised. I looked at you and saw a house, not a man. I saw an opportunity, not the person who—”

She couldn’t finish.

Gordon turned to me. “Dad, why didn’t you ever tell me you were a firefighter?” he asked, voice breaking. “Why didn’t you mention you’d saved a child like that?”

I shrugged, feeling suddenly very old. “It was my job,” I said. “We went in when there was someone to save. Most nights, I came home, took a shower, and tried not to think about the ones we didn’t reach.”

“You changed our lives,” Thomas said. “And we never even knew your name.”

We sat there with all of it between us—the fire, the scars, the insults, the real estate letter, the catalogs tagged with plans for rooms she didn’t own. I thought of all the legal walls I’d built, all the ways I’d prepared to fight her in court.

“I went into that house for a frightened seven-year-old who deserved another chance at life,” I said finally. “Not for the woman who walked in here and treated me like luggage standing between her and a prize.”

Pearl flinched like I’d struck her.

“But,” I added, “I see you understand that now. That’s more than an apology, and less than a solution. So here’s where I stand.”

They all looked at me.

“I forgive you,” I said.

Pearl’s mouth fell open.

“That doesn’t mean I trust you,” I continued. “Forgiveness is free. Trust is earned. If you want to be part of this family, you’re going to have to show—over time, not in one grand gesture—that you’re not the woman who made that joke on my porch. That you’re closer to the girl I carried out of a burning bedroom. Do you understand?”

She nodded, tears spilling again. “Yes,” she whispered. “I’ll prove it. I will. I don’t deserve it, but I will.”

Thomas and Donna were crying too, now from a different kind of emotion. Gratitude and shame and relief all tangled together.

They left that night hugging me like I was some kind of miracle. Gordon and Pearl went second, quieter than I’d ever seen them. At the door, she turned back.

“Thank you for saving me,” she said. “Both times.”

I watched their car disappear down the street, then went back to the dining room, where the food had gone cold. I put everything away in plastic containers, washed the dishes, flipped off the lights, and sat in my recliner in the dark.

I’d prepared for war. Instead, I’d gotten something messier: the truth.

In the weeks that followed, Pearl showed up at my house alone on Saturday mornings with coffee and no agenda.

“I started seeing a therapist,” she said one day, sitting on the porch swing while the Portland rain drizzled gently off the eaves. “She specializes in trauma. Apparently, building your whole personality around never needing anyone isn’t healthy.”

“That tracks,” I said.

She winced but smiled a little. “I know it doesn’t fix everything. But I want you to know I’m trying to be someone Gordon can be proud of. Someone you can at least tolerate.”

We talked in small doses. About the fire. About the scars she still hid. About Marie. About Gordon as a kid, running through this very yard with a plastic fire helmet on his head, yelling “I’m like you, Dad!” while I watched from the porch.

When the wedding came—a small, simple ceremony in a garden outside the city rather than the huge production she’d wanted at first—I sat in the third row and watched my son’s face as he said his vows. He looked steady. Not dazzled. Not desperate. Steady.

Afterward, at the reception, Pearl’s parents introduced me to every relative within reach as “the man who gave us our daughter.” She rolled her eyes at them, embarrassed and oddly human.

A month later, Gordon called.

“We found a place in the Hawthorne district,” he said. “Two bedrooms, small but ours. Pearl said we needed to start our marriage in our own space, not with one foot in yours.”

“That’s good,” I said. And I meant it.

One evening in late summer, as the heat finally let up and the sky over Portland turned that pale pink it gets before dark, I sat on my front porch with a letter in my hand. It was from Pearl, three pages of careful handwriting.

She didn’t ask for anything in it. Didn’t argue her case. She just cataloged everything she’d done to me and my house, point by point, and apologized for each one. She told me about therapy, about nightmares returning, about learning to sit with guilt instead of outrun it. She thanked me again, not just for the night of the fire, but for not letting her win when she was at her worst.

“You saved my life again,” she wrote, “by refusing to be the weak one in the room.”

I wrote back a short note.

“I see the work you’re doing,” I wrote. “Keep doing it. Respect is built, not gifted. I’m willing to see where this goes.”

Now, some evenings, my phone buzzes and it’s Gordon asking if I want to grab dinner downtown, or Pearl sending a photo of their cramped but cheerful apartment with a caption about how “this couch would never have fit in your living room, and that’s okay.”

My legal papers are still in the safe, signed and sealed. The house will go to the firefighters’ fund when I die, just like we planned. The difference is, I no longer feel like I’m brandishing those papers against an enemy. They’re just part of my story.

The real battle was never about square footage or market value. It was about whether I could protect what I’d earned without losing who I was. It was about whether a scarred, lonely old firefighter could stand his ground without becoming cruel in return. And, maybe, whether a girl who survived a fire in Portland could set down the armor she built afterward without falling apart.

Some nights, when the streetlights come on and the MAX rumbles faintly in the distance, I sit on the porch, listen to the city, and think about that burning house in 2000. The little girl hiding in the closet. The man I was, running into danger because someone needed me.

If you’d told that younger version of me that the girl I carried out would grow up to be my biggest problem and then, somehow, a second chance at family, I’d have said you were out of your mind.

Life in America has a way of circling back on you like that. Streets you think you’ve left behind show up again on the GPS. People you rescue turn up on your porch years later, wearing expensive boots and saying terrible things, and then, if you’re both lucky, sitting on your swing with coffee and trying to do better.

I lock my front door at night and smile to myself.

My house, my peace, my life. Still mine.