On a cold American morning in early October, a little girl in a purple jacket stepped out of a modest suburban home in Westminster, Colorado, and let the door close behind her. The neighborhood was the kind people move to because it feels safe: quiet streets, snow-dusted lawns, kids’ bikes left in driveways, the flag out front still and frozen in the chill. Her mother watched her go backpack on, orange in hand, blonde hair tucked into her coat never imagining that this ordinary walk to school in the United States would be the last time she ever saw her daughter alive.

The girl was 10-year-old Jessica Ridgeway. She lived in a multi-generational home with her mom, Sarah, her grandma, and her aunt. Her parents, Sarah and Jeremiah, had separated years earlier. He lived in Missouri, and although there had been disputes over custody and child support, Jessica was one of those rare kids of divorce who still managed to be close to both parents. They adored her; she adored them.

At school Witt Elementary, a public school in the Denver metro area Jessica was the kid teachers secretly hope every class will have. They described her as bright and endlessly cheerful, a child who smiled with her whole face. She volunteered to help with anything. She always put her hand up first to answer a question or welcome a new student. If you stuck her in a room with strangers, she’d walk out with friends.

She loved TV shows like “Victorious” and “Wizards of Waverly Place,” worshiped animals, and was always inventing dance routines and silly songs. She wasn’t the type to give up easily; if something didn’t click right away, she kept trying, laughing at herself, determined to get it right. Her grandma called her exuberant. Her mother said the house felt louder, brighter, funnier when Jessica was in it.

On the morning of October 5, 2012, in that sleepy Colorado suburb, Jessica’s alarm clock went off at 7:45 a.m. sharp. She’d begged her mom for that alarm clock because she wanted to be more independent, more “grown up.” She woke herself up, turned on the TV for a few minutes, ate a granola bar, and got dressed for the cold. Before she left, she stood next to her mom in the kitchen, peeling an orange they’d decided she would take as a snack.

Her winter coat thick, dark, practical went on. Her backpack, filled with everyday kid stuff, went over her shoulders. It was just another school day in America. Nothing epic, nothing remarkable, not yet.

She said goodbye and headed out into the sharp Colorado air, walking down the sidewalk she knew by heart. The plan was the same as always: she would walk a short distance to Chelsea Park, only a five-minute stroll from her street. That’s where she met her friends every morning before they all walked to Witt Elementary together. It was their ritual.

But on that Friday morning, something went wrong.

Jessica never showed up at the park.

Her friends waited awhile, shuffling their feet in the cold, checking the time, nervous about being late. Eventually, they gave up and walked to school without her.

Jessica loved school. She wasn’t the kind of kid who stayed home just because it was chilly or she was “tired.” She didn’t take random days off. She didn’t disappear. So when 10:00 a.m. rolled around and she still hadn’t arrived, the staff at Witt Elementary knew something was off.

They called her mom.

But Sarah wasn’t up. She worked overnight shifts 10 p.m. to 7 a.m. and after seeing Jessica out the door, she had collapsed into bed and into deep, exhausted sleep. The school left a voicemail.

At 4:30 p.m., that message finally reached her.

She woke up, listened, and felt immediate confusion. There had to be a mistake. Maybe Jessica had gone to a friend’s house after school. Maybe someone forgot to check her in. Maybe this was a clerical screwup.

Sarah jumped in her car and started driving. First to the park. Nothing. Then to the school. No sign of Jessica. She checked the homes of her daughter’s close friends. No one had seen her.

That’s when the denial crumbled.

Sarah picked up the phone and called Westminster police.

“My daughter’s missing,” she told the dispatcher. She explained that Jessica was supposed to walk to school, that the school was now saying she never arrived, that it was already late in the day.

“How old is your daughter?”

“She’s ten.”

In that moment, something shifted inside Sarah, and inside the officers hearing the call. Every parent’s nightmare had stepped out of the realm of hypothetical and into their street.

By about 9:15 p.m., after talking to school staff, family, neighbors and reviewing the timeline, investigators were already thinking the same thing: this wasn’t a case of a kid wandering off. They believed 10-year-old Jessica had likely been abducted. The Colorado Bureau of Investigation issued an AMBER Alert.

On local TV news across the Front Range, the smiling school photo of a small blonde girl flashed onto screens. Anchors told viewers this was a serious situation in an ordinary Colorado suburb, that an American fifth grader had vanished between her front door and her school.

Jessica, they said, was 4’10” tall, with shoulder-length blonde hair and blue eyes, wearing a black winter jacket. A reporter stood near Chelsea Park in the creeping darkness, telling viewers that this was where Jessica normally met her friends, that on this day she never made it, and that hundreds of people were already searching.

By then it was dark and brutally cold. Firefighters rolled out equipment that could see heat signatures in the night thermal imaging cameras to sweep the park and nearby areas. Bright floodlights turned parts of the park as bright as day. Investigators wanted a helicopter equipped with night vision, but icy conditions made flying too dangerous; the blades could ice up.

“We’re using every resource we have,” a police spokesperson told the cameras. “We’re trying to get air support, but the weather has grounded those. So we’re relying on ground and specialized equipment.”

They called for volunteers the next morning. They didn’t have to ask twice.

Over the next days, what had been a quiet American suburb transformed into the center of a massive search operation. Officers combed through backyards, sheds, garages, and basements, with residents’ permission. They moved through open space, creek beds, brushy areas, and tree lines. They set up checkpoints at intersections to write down license plates and photograph vehicles going in and out of the neighborhood.

Hundreds of people came to help. By some estimates, more than a thousand volunteers eventually joined the effort. Ribbons in Jessica’s favorite color purple appeared on mailboxes, trees, front doors, and car antennas. For those who didn’t know the Ridgeway family personally, the ribbons became a way of saying: we’re watching, we care, and whoever did this is not welcome here.

Inside the police station, the scale of the work exploded. Detectives took about 700 DNA samples from people who lived or worked in the area or fit any part of a vague profile. They interviewed parents, teachers, neighbors, sex offenders, exes, and relatives. The FBI joined, bringing federal resources, evidence teams, and behavioral analysts. More than a dozen agencies shared information.

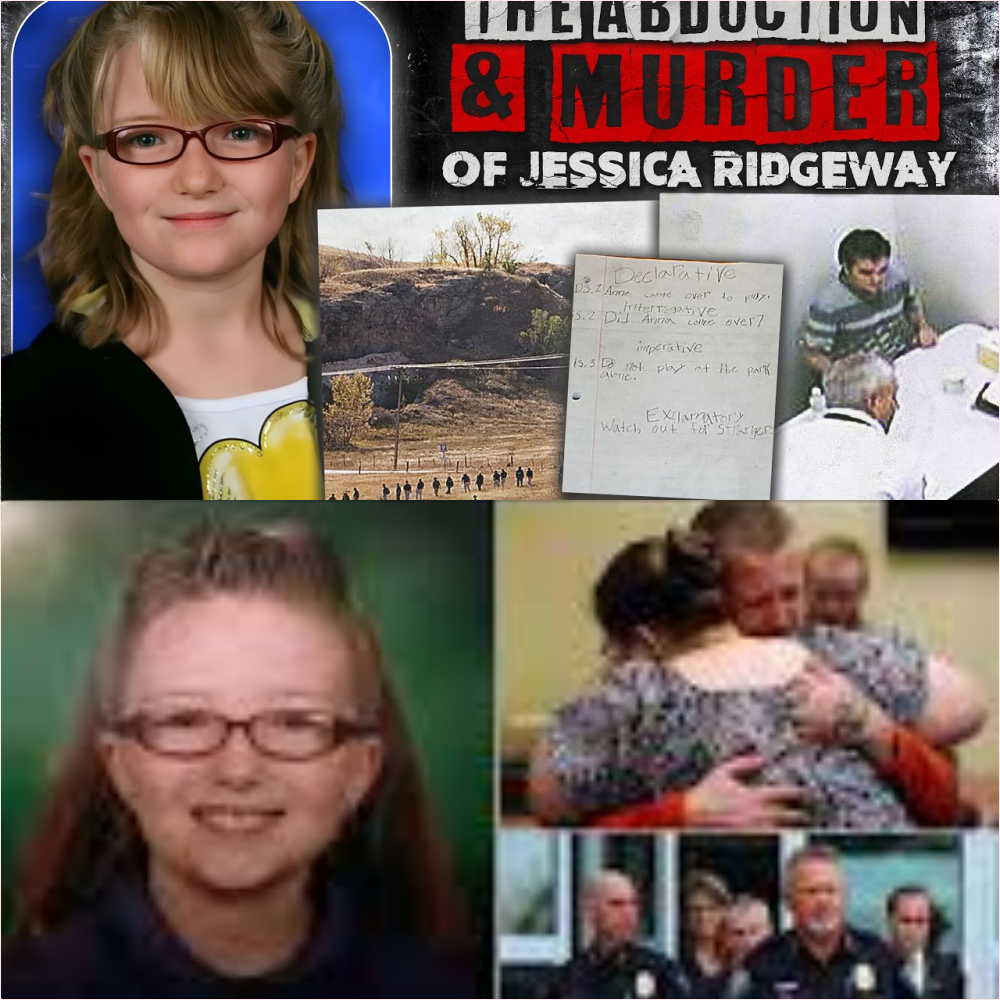

In Jessica’s bedroom, officers found something that hit like a punch to the gut: a notebook from school. On one page, the 10-year-old had written a line, almost like a personal rule: “Do not play at the park alone, and watch out for strangers.”

She’d been careful. Adult after adult who knew her said the same thing: she was wary, not trusting of strangers, the kind of child who’d been taught safety rules and actually followed them. That left investigators with two possibilities either someone she knew and trusted had lured her, or she had been snatched so fast she had no chance to react.

Days passed. Rumors started swirling. Some focused on her father in Missouri because of the custody dispute. Police looked, but quickly said they did not believe she was with him. They didn’t publicly rule him out right away they rarely do but they focused more and more on the idea of a stranger abduction.

Four days after Jessica vanished, her family stepped outside their home to face cameras for the first time. They had been cooperating with investigators, giving DNA samples, answering every question. But until that day, they hadn’t felt able to leave the house.

Sarah stood there, shaky but determined, and spoke about her daughter, calling her “my rock” and begging for her safe return. Jeremiah, her father, traveled from Missouri and stood beside her, struggling to hold himself together as he told reporters he just wanted to find his little girl. They were united in grief and fear.

Behind them, while they spoke, an FBI mobile evidence team later moved into the house, donning gloves and protective covers over their shoes, sweeping through rooms with cameras and kits, looking for any clue that might tell them what had happened after that front door closed on October 5.

But the longer Jessica was gone, the harder it became to hold on to hopeful scenarios.

Then, a small glimmer: about six and a half miles away, in the neighboring community of Superior, a man out for the day noticed a backpack, a pair of glasses, a water bottle, and some clothing that looked oddly out of place. The clothes, he later recalled, had a strong odor. Sprawled near a path in another subdivision, the items looked discarded, not dropped.

On the backpack was a keychain with a name: Jessica.

Knowing nothing about the missing child from Westminster, the man mentioned the discovery on a neighborhood message board, offering the items up to whoever they might belong to. Someone reading that post made the connection to the AMBER Alert and called 911.

When Sarah heard that Jessica’s backpack had been found, she felt a flash of hope. Maybe she’d run away and dropped it. Maybe someone had taken the bag but not her. Maybe this meant she was still alive somewhere.

“I felt a sliver of hope,” she later said. “I figured, if something really bad had already happened to her, they wouldn’t just leave the backpack like that.”

That hope didn’t last long.

The next day, maintenance workers in a different area, in the suburb of Arvada, about six miles from Jessica’s home, noticed a heavy bag near a roadside by a park. Something about it seemed wrong. Instead of opening it, they called a nearby police officer.

Inside that bag, officers found human remains.

At first, authorities would only say publicly that they had found a body, that they believed it was a child, and that identification would take time. But privately, multiple sources told journalists they feared the remains belonged to Jessica.

Testing confirmed it. The remains were hers. Her body had been dismembered.

Even then, investigators didn’t yet know exactly how she had been killed. A cause of death would take more examination. But they did know one thing: somewhere in metro Denver, a predator had snatched a little girl on her way to school, killed her, and dumped her remains in more than one location.

The language at press conferences changed overnight. “Our focus has shifted,” Westminster’s police chief announced, “from the search for Jessica to a mission of justice for Jessica. We realize there is a predator at large in our community.”

Vigils sprang up across Westminster and nearby cities. At one, hundreds of people gathered with candles and purple ribbons, singing, crying, praying. Parents struggled with what to tell their own children about what had happened to a girl their age in a neighborhood that could have been theirs, in an American city that looked like any other.

“It feels like it takes pieces of their childhood away,” one mom said, tears in her eyes. “You want to tell them the world is a good place, but then this happens, and you’re suddenly telling them they can’t talk to strangers, that they have to be careful all the time.”

While the community mourned, investigators dug deeper. They combed through offender registries, pulled phone records, and even analyzed data from cell towers near the key locations: Jessica’s route, the park, the spot where her backpack was found, the area where the bag with her remains had been abandoned. If the same phone number pinged those towers at those times, that might point to someone.

Then, a DNA hit.

Months earlier, on Memorial Day, a jogger near Ketner Lake just a stone’s throw from where Jessica likely encountered her abductor had been attacked from behind by a man wearing a mask. He’d shoved a cloth that smelled chemical and strange over her face, trying to drag her off the path into the brush.

The woman fought back, managed to break free, and ran, terrified, for help. She could only describe her attacker in general terms: a white male, average build, maybe around 5’6″ to 5’8″, based on how he felt when he grabbed her. Police collected evidence from that scene, including DNA from contact with her body.

Now, comparisons showed that the DNA from the jogger’s case matched DNA linked to Jessica’s case.

It was the same predator.

Agents from the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit drafted a profile and pushed out a message to the public. This wasn’t just about looking for a suspicious stranger in a van; they wanted people to think about the men in their lives.

They asked neighbors, friends, co-workers, and family members across the area to look for sudden changes in someone they knew after October 5: a man who shaved off facial hair he’d had for years, suddenly dyed or cut his hair, began parking his car in the garage instead of the driveway, seemed nervous, depressed, or strangely on edge. Someone who missed work, withdrew socially, or acted as if he was carrying a terrible secret.

“Unfortunately,” one FBI spokesman said, “this is likely somebody’s neighbor, somebody’s friend, somebody’s family member. We suspect someone knows who this person is.”

Tips poured in more than 4,000 by some counts. Among those watching the news coverage was a woman who lived near a young man named Austin Sigg.

She’d seen the photograph of a small wooden cross necklace that police had recovered and released to the public, asking if anyone recognized it. The cross looked familiar to her. So did the general description of the attacker, and the mention that he might have an interest in dark topics, in death, in decaying bodies.

The neighbor thought of Austin.

At 17, Austin lived with his mother, Mindy, in the same region of Colorado. People who knew him described him as intelligent but socially awkward, often alone, with an interest in morbid subjects. The neighbor called the FBI and told them her concerns.

Soon after, agents knocked on the Sigg home’s door.

They found Austin polite, if quiet. He answered questions. He said he’d been home sleeping the morning Jessica disappeared. Agents noticed he wore a cross resembling the one in the photograph. They asked him for a DNA sample. He agreed.

Every day, dozens of samples were being collected in the case and sent to labs with the names of the donors. The process was like a massive elimination game run each sample, look for a match to the known DNA from Jessica and the jogger, then move on.

When Austin’s envelope came back, it was empty. Somehow, in the shuffle, his sample hadn’t been tested. Standard procedure was to assume an empty envelope meant no match, so investigators, drowning in leads and tips, set his name aside and kept going.

It might have stayed that way if Austin’s own conscience or something like it hadn’t cracked.

On October 22, news broke widely that the DNA from the jogger attack and the DNA from Jessica’s case were the same. That there was a serial predator at work. That he was still out there.

At school that day, Austin told classmates he felt shaky and physically sick. That night, he slept in his mother’s bed, like a scared child. Mindy later said she could tell something was very wrong.

The next morning, he told her he needed to talk.

She asked the question that had been lurking in the back of her mind, the one every parent would dread but almost none would say out loud.

“Is this about Jessica?” she asked him.

“I just knew,” she said later. “I don’t know why, but I just knew.”

He told her yes. He told her what he had done. That he had taken a 10-year-old girl, hurt her, and that what was left of her was in their home.

Mindy collapsed to the floor, sobbing. She said her first instinct was disbelief this couldn’t be her son, the baby she’d raised, the boy she’d once known as kind and sweet. But the details he gave her left no room for denial.

“I’m going to prison,” he told her.

“I know,” she replied. And then she told him what needed to happen next: he had to turn himself in.

“I can’t do it,” he said. “Can you call for me?”

So she did.

She dialed 911 and, in a trembling voice, told the dispatcher that her son wanted to confess to the murder of Jessica Ridgeway. She said he’d given her details only the killer would know. She said he claimed there were remains in the house, though she could not bear to see them herself.

The dispatcher kept her on the line, asking if her son was cooperative, if she felt safe, asking if Austin would talk directly. He took the phone, his voice calm but urgent, telling the dispatcher he had murdered Jessica, that there was proof, that officers just needed to come and he would answer every question.

He also admitted, briefly and matter-of-factly, that he’d been the one who attacked the jogger months earlier, using a homemade chemical-soaked cloth. That he had planned to abduct her too.

The call lasted almost eighteen minutes as officers raced toward the house in Westminster, approaching quietly in plain clothes at first, then identifying themselves at the door. Mindy told the dispatcher when she saw them through the window. Then she opened the door and let them in.

Nineteen days after Jessica Ridgeway set out for school and never arrived, the teenager who took her was sitting in a police interview room.

Over the hours that followed, in taped interviews with investigators, Austin answered questions about Jessica, about the jogger, and about himself.

He told them that on October 5, he hadn’t had a specific target in mind when he left home. He described himself as “hunting,” driving around until he saw someone vulnerable and alone. The woman at Ketner Lake had been too strong and had gotten away. This time, he wanted someone smaller, someone he could easily overpower.

He noticed Jessica playing in the snow at Chelsea Park, making snowballs, a backpack on her shoulders. He watched her. He parked his Jeep in a way that kept him partly hidden, then waited. When she walked by his vehicle, he jumped out, grabbed her, and pulled her inside.

Jessica screamed, he said, but there was no one close enough to hear or intervene. He restrained her and lied to her, telling her she would be okay, that she’d go home soon, that he knew her mom. He drove her back to the house he shared with his mother.

Exactly what happened inside that house in those horrific hours is known fully only to him. He admitted to investigators that his motives were driven by a violent sexual obsession, but he insisted he did not commit certain acts that prosecutors believed he did. What is known is that he kept her there, changed her clothes, cut her hair, and at some point killed her.

From the moment he pulled her into the car, he told them, he knew she was going to die.

After her death, he tried to dispose of her body in ways he’d read about and seen in crime stories and forensic materials. He dismembered her, kept some of her remains hidden inside the house, left others in a pool shed for a time, then drove out to discard what he could. Investigators would later find evidence in a crawl space, in the pool shed, and in the plumbing, confirming that the disposal efforts had been as disturbing as they were calculated.

He admitted that he’d taken her backpack, water bottle, and some clothing and dumped them in another neighborhood to throw off the investigation. The items were apparently chosen deliberately the glasses that made it clear she wasn’t just off hiding somewhere, the clothing that still carried the marks of fear and shock from that day.

When detectives heard all of this, they ordered his old DNA sample to be retested and this time, properly processed. The result was immediate and undeniable: his DNA matched the profile from Jessica’s case and the jogger attack.

Officers seized his Jeep and found broken zip ties consistent with his story. They took his computers and devices and uncovered a long history of consuming illegal child exploitation images and violent content, a digital trail of a teenage mind burrowing deeper and deeper into darkness.

Austin told them his obsession had started when he was around 12, escalating over the years into more abusive and extreme material. His parents had known something was wrong. Years earlier, they’d taken him to a Christian counselor over his viewing habits and emotional struggles. For a short while after therapy, he said, he felt like he had things under control. But it didn’t last. The urges crept back in, worse, more intense.

Doctors had once contacted his father, urging him to strictly limit Austin’s access to screens and content. There were references to physical issues when he was a baby, surgeries, and complications, and his defense team later would hint at early brain trauma or developmental complications. But none of that changed the brutal reality of what he had chosen to do to a little girl in an American suburb.

As news broke that the suspect in Jessica Ridgeway’s murder was a 17-year-old from just a few miles away, shock rippled through the community.

Neighbors began connecting uneasy dots. One woman said that the day news of Jessica’s disappearance first spread, her own 11-year-old daughter had told her she had a bad feeling about a particular teenage boy the “goth kid” from the park who stared at her and made her friends uncomfortable. At the time, the mom had dismissed it as childish fear.

“I feel terrible I didn’t listen to her instinct in that moment,” she said later. “If she had been at the park alone that day, who knows what could have happened.”

Prosecutors charged Austin Sigg as an adult, despite his age. The charges were staggering: multiple counts of first-degree murder, kidnapping, sexual assault of a child, sexual exploitation of a child, robbery, and, in the case of the jogger, attempted murder and attempted kidnapping.

He was moved to the Jefferson County Detention Center and held in special housing, separated from the general adult population. Even behind bars, at least for a time, he managed to unsettle people. Guards and officials described his demeanor as calm, flat, oddly detached from the horror of what he’d done.

His father, who had his own history of run-ins with the law, released a statement expressing heartbreak and condolences to the Ridgeway family and describing Mindy’s decision to turn her son in as an act of courage. There were hints of a chaotic family past, but no evidence that Austin had been abused or neglected in the classic ways psychologists look for. A forensic psychologist who reviewed records and reports said there was no sign of severe trauma in his childhood, and that he came from a family that, at least in many respects, had tried to support him.

What stood out, she noted, was his lack of empathy, his chilling ability to talk about his crimes in a detached, almost analytical way.

At first, in court, Austin entered a plea of not guilty to all charges. It stunned observers, given his extensive confession and the evidence found in his home.

The not guilty plea was widely believed to be a strategic placeholder, a way for his defense team to preserve certain options while they assessed whether they might claim some form of mental illness or diminished capacity. They floated theories about prenatal injuries, about head trauma, about a complicated medical history. They pointed to his age, under 18, arguing that the system should remember he was, legally, still a minor at the time of the crime.

Prosecutors responded that age alone could not begin to offset what he had done. They laid out his online search history: homemade chemical mixtures, ways to incapacitate someone, “top places people get abducted,” methods of hiding or destroying remains. They described how he had attacked one victim, failed, and then escalated until he succeeded with Jessica.

“The founders of this country did not write into the Constitution an exception that says when a young man kidnaps, robs, sexually assaults, murders, and dismembers a 10-year-old girl,” one prosecutor said in court, “that everything except the murder should be excused. What we know is that this young man is dangerous. The only way to protect the community is to ensure he never has the opportunity to do this again.”

Colorado law meant that, as a juvenile at the time of the killing, he could not face the death penalty. If convicted on first-degree murder alone, he would face life in prison with the possibility of parole after 40 years.

For Jessica’s family, the idea that he might walk free someday, even as an old man, was unbearable.

They braced themselves for a long, ugly trial, for the possibility of having to sit in a courtroom and listen to every one of those sickening details replayed, challenged, and dissected. The community braced with them.

Nearly a year after Jessica’s abduction, and just two days before jury selection was set to begin, the case took a sharp turn.

Austin changed his plea.

Standing in court, in a county in the state of Colorado, in front of the judge and a packed gallery, he pleaded guilty to most of the charges against him: first-degree murder, kidnapping, sexual assault of a minor, sexual exploitation of a minor, robbery, and the charges related to the attack on the jogger.

There was no plea bargain. No concessions. The district attorney’s office made it clear: they had offered no deals. He was simply choosing to plead guilty.

At sentencing, prosecutors argued for the harshest possible punishment allowed by law. The judge listened to days of testimony and statements not only from law enforcement and experts, but from Jessica’s family, friends, and members of the community who had searched for her in the cold and mourned her when she was found.

He was ultimately given life in prison for the murder of Jessica, plus an additional 86 years for the other crimes those years stacked on top of each other, not run concurrently. The structure of the sentence removed any real possibility of parole. In practical terms, it meant he would die behind bars.

The judge said the case “cries out for a life sentence,” stressing that nothing could fully capture the horror of what had been done or the pain inflicted, but that the system had a responsibility to do everything in its power to ensure he could never hurt anyone else.

When the judge asked Jessica’s family whether they wanted to address the court in front of Austin, her mother made a choice that caught many off guard.

She stood and said she would not speak directly to him. She refused, she said, to give him the power of hearing how deeply he had hurt her, her family, and the community. He didn’t deserve to know how much damage he’d done. Once they walked out of that courtroom, she said, they would not carry his name; they would carry Jessica’s.

Reporters in the room described Austin as largely expressionless throughout, answering the judge’s questions mechanically, showing no visible emotion as he was sentenced to spend the rest of his life in a prison somewhere in the United States.

Outside the courtroom, District Attorney Peter Weir told the press that there had been no negotiations. “We were not going to make any concessions for Austin,” he said. “Not in a case like this.”

Back in the life she had to rebuild, Mindy threw herself into therapy. she said she had never second-guessed calling the police that day, even though it meant turning in her own son. She said she didn’t believe anything she did had “made” him into what he was, but she still carried the unbearable weight of knowing that the person who had destroyed another family’s life was someone she had brought into the world.

She said she had not spoken to Austin since the day he confessed in that house. He had not reached out to her either. Part of the reason, she explained, was that she didn’t believe she would get the truth from him, and she couldn’t bear to be lied to.

“If I could trade my life for Jessica’s, I would,” she said. “Even now, if there were any way, I would do it.”

Jessica’s grandmother, speaking with remarkable grace, said that every member of their family felt a deep compassion for Mindy. “We understand that she has lost a son too,” she said softly. “It’s not the same loss, but it is still a loss. My heart goes out to her. If we could have hugged her in court and it would have been allowed, we probably would have. We think about her a lot.”

In the years that followed, the community of Westminster and the broader Denver area refused to let Jessica be remembered only for the way she died.

A memorial playground was built in her honor, in a park that had been transformed by the community’s grief and love. Everywhere you looked there, purple appeared on rails, on accents, on signs a nod to her favorite color. There was a custom track ride, about 40 feet long, that let kids soar and laugh the way she once had. “Knock-knock” jokes, submitted by her classmates, were imprinted on parts of the playground, so that her friends’ childish humor became part of the landscape.

There was a special swing set with a ribbon design, custom-made. Parents brought their kids to play and told them about a girl named Jessica who loved to laugh and go to school, who had trusted the world enough to walk to her friends in the morning.

Out of her story, a safety initiative also grew: The Lassy Project, a free service designed to help parents and guardians rapidly alert nearby communities if a child went missing. In a country where child abductions, though rare, send shockwaves every time, the idea was to harness the power of local networks in seconds, instead of hours, when time matters most.

Jessica had wanted to be a cheerleader someday. She talked to her mom about it, saying that when she was finally old enough, she would join cheer, and she promised she’d be the kind of cheerleader who was kind to everyone, not the mean stereotype people make jokes about.

In her memory, a cheer camp was set up in her name. Little girls in purple bows and uniforms learned routines and chants and, hopefully, the lesson that being “the cheerleader” doesn’t have to mean being cruel or exclusive. It could mean lifting others, being the one who encourages and supports.

Five years after the day the front door closed on Jessica for the last time, Sarah held another baby in her arms a little girl named Anna Christine. She gave Anna the same middle name as Jessica, tying the sisters together in a small, quiet way.

In their home, Jessica was everywhere. Photos of a smiling 10-year-old girl. Decorations and objects in purple. Little reminders tucked into shelves and frames. They still talked about her, not as a ghost to be whispered about, but as someone who remained part of the family’s story.

“We still talk about her,” Sarah said. “She still exists for us. The hardest thing anyone can ever do is move forward after losing a child. But I need to remember who she was, who I hoped she would become, and I need to keep moving forward.”

They noticed little things with Anna. Her blue eyes different from Jessica’s shade, but blue all the same. The way she seemed sometimes to look off at something no one else could see, as if someone were standing just beyond the edge of what adults can perceive.

“Sometimes,” they said, “it feels like her big sister is somewhere close. Like she’s watching over her in her own sparkly way.”

They planned to tell Anna everything when she was old enough not to terrify her, but to give her the truth. To let her know that she had an older sister who had lived and laughed and loved, and whose story, as heartbreaking as it was, had also changed a community.

“We don’t want to raise her in fear,” Sarah said. “I don’t want what happened to overshadow everything. I don’t want to smother her. I want her to have her own life. Jessica is not replaced. Our family has expanded. But yes, Anna has a very special guardian watching over her.”

When Sarah tried to explain the impact of her daughter’s murder, she reached for an image.

It was like a plate, she said, shattering on the floor. You can pick up the pieces, you can glue them back together, you can hold them in your hands and say, “This is still a plate.” From far away, it might even look whole. But up close, the cracks are there. The missing shard that slid under the couch or broke into dust is always missing. No matter how carefully you assemble the pieces, it will never quite be the same.

On that October morning in an American suburb, a little girl in a purple jacket walked out of her house with an orange in her hand, ready to meet her friends and see what the day at school would bring. She never got there. The walk was short, the distance small, but in those few blocks, a stranger’s darkness collided with a child’s everyday joy.

The community of Westminster, of Colorado, of the United States, could not rewind time. They could not change the icy air that morning or make someone happen to drive by at the exact moment she was grabbed. What they could do and did was refuse to speak of her only as a victim.

They built swings and slides in her color. They engraved jokes and memories. They shared her story, not just as a warning about danger, but as a remembrance of who she really was: a bright fifth grader who loved to learn, a dancer in the living room, a kid who promised to be kind even when she someday made the cheer squad.

In the end, the name that mattered most was not the one on the court documents. It was the one written on a backpack keychain, on purple ribbons, on playground plaques, on the hearts of people who never even met her but still say her name.