The lights in Baltimore City District Courtroom 3B burned too bright, bleaching the varnish on the benches and catching the curl of two uniforms’ smiles as if the fluorescents themselves were witnesses. Laughter—quiet, sideways—spilled between them like contraband. It was the kind of laugh men share when they believe the world bends toward their convenience. They sat second row center, service pins winking, blue shirts pressed to parade stiffness: Officer Frank Miller with the bulldog neck and the jaw that liked to grind, and Officer Greg Sullivan, lighter, thinner, a pair of bright, ferret-nervous eyes set above a sympathetic nod he’d practiced in his bathroom mirror. They were the show before the show. Their smirks were warm-ups. Their whispers were already writing the conclusion.

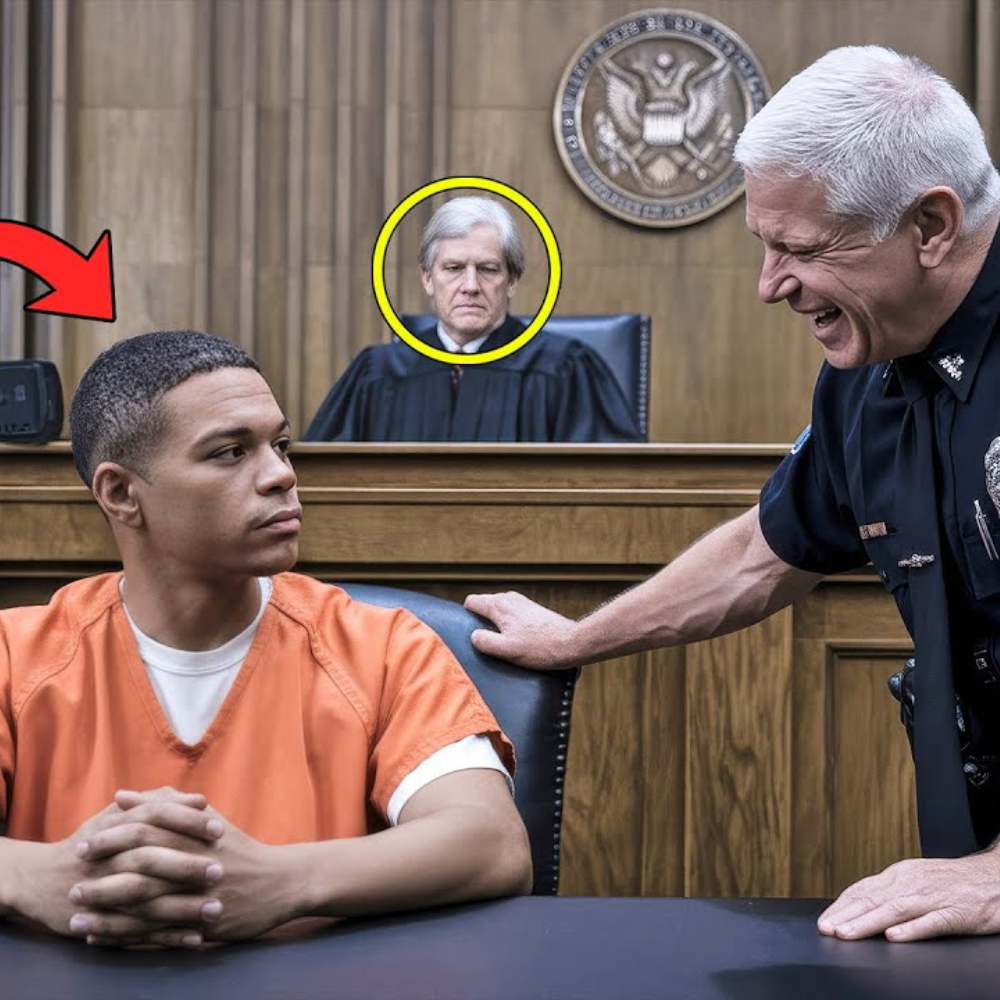

Up front, in county-issue scrubs the color of defeat, the defendant stared at a knot in the wood as if it could tell time. The docket called him Michael Johnson. He looked exactly like the story the prosecution needed: a man from the wrong block with tired shoes and no one to pay for a better suit. He was tall, lean through the chest and shoulders, the quiet physical confidence of someone who’d known how to move in rooms with worse lighting than this. His hair wasn’t done. His face gave nothing. He stood when told to stand, sat when told to sit. If you didn’t know better, you’d think you knew everything.

Judge Emily Reed squinted over her glasses with a face that had been honed by twenty years of saying no. “Case 774B,” she said, gavel poised. “The People of the State of Maryland versus Michael Johnson. Charges: aggravated assault on a peace officer, resisting arrest, possession of a controlled substance.”

A bailiff yawned so softly only the court reporter noticed. Assistant District Attorney Kyle Jensen—Baltimore County’s slick pony in a $300 suit he swore looked like four figures—adjusted his tie knot as if tugging the truth straighter. “Your Honor,” he began, voice rich with borrowed righteousness, “the facts are painfully simple.” Two of Baltimore’s finest. A West End patrol. An erratic subject. Clear signs of narcotics intoxication. The language fell out of his mouth like a form he’d filled a hundred times.

In the second row, Miller and Sullivan leaned back with the confidence of men who believed the city was their biography. They had already testified. They had polished their stories until they gleamed: a scene in which they were guardians, the man in scrubs a danger that had to be contained. They had practiced the pauses, the pained hand-to-ribs, the nod to “community safety.” It was easy work if you didn’t count the contempt.

The defendant didn’t look at them. He looked at the jurors: a retiree with a tidy knit cardigan and the burdened patience of a grandmother; a younger man in a plaid shirt who kept his hands clasped a little too tight; a nurse from the east side; a postal employee who took notes the way he probably did at route meetings. The defendant watched the judge too, and the ADA’s posture, and the bailiff’s boredom, and the way Miller smiled without the courtesy of shame. He saw the whole room because he’d been trained to build rooms like this from memory. The man under the paper name Michael Johnson had done more dangerous things than this trial in places where the law arrived late if it arrived at all. He was, in the life he was not living in this moment, Director Michael Thorne of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

He was also the most dangerous kind of defendant: a patient one.

Sarah Jenkins, public defender, shuffled her papers as if noise could thicken her. Five years out of law school, she wore the outer skin of a woman who’d learned how to apologize for too many clients at once. She had a pen that clicked when she was nervous, which, today, it seemed, was often. “Not guilty, Your Honor,” she said softly when asked for a plea. The prosecutor’s table sighed like a chorus. A juror rolled her shoulder as if getting comfortable for the inevitable.

“Very well,” Judge Reed said. “Mr. Jensen, call your first witness.”

“The People call Officer Frank Miller.”

The uniform stood with a heavy’s certainty, taking the oath like a box to be checked. He settled into the witness chair, broad shoulders owning the space. His voice found the microphone. He described the 900 block of Monroe Street as if it were a creature: a “hotbed,” a “known corridor.” He painted a scene where concern met chaos, where a simple welfare check—those two words are America’s favorite prelude—turned into a violent attack. He described necessity. He described restraint. He described a man with “that look” in his eyes, the look that lets certain officers convince themselves they have already seen the end of the movie.

Across the room, the man in scrubs did not blink when Miller gestured with a small flick of two fingers in his direction—an almost invisible signal that said “his type” without the clumsy ugliness of old words. The juror in the back row, a Black woman with a steady face, sat a little straighter.

Jensen displayed the small evidence bag. Its contents—a bindle of powder—looked like every street-corner vice photo ever laminated for a press conference. “Found in his left jacket pocket,” Miller confirmed, the lie polished until it could pass any quick inspection. The body cameras? Broken, both of them, in “the violent struggle,” a phrase that melted across the courtroom like butter on a hot plate.

“Your witness,” Jensen said with the flourish of a man tossing a paper airplane he was sure would fly.

Sarah rose. “Officer Miller, you testified you observed signs of narcotics use. Are you a medical expert? Did you perform a test?”

“Ma’am,” Miller said, smiling a small, practiced smile, “twenty years on the job. You learn to recognize what you see.”

“And ‘what you see’ includes a lost camera system on both officers?” she followed, eyes on the file, voice almost apologetic.

He spread his hands. In a fight, things break. She pressed—very gently—about weapons, about escalation. He gave the jury a little shrug, the kind of shrug juries believe because it carries the weight of a uniform. The performance had been rehearsed; it landed as intended. Sarah returned to her chair looking exactly as outmatched as Miller needed her to look.

Officer Greg Sullivan took the stand a minute later and played the other half of the script: the good cop. His steps were careful, his hand brushed his ribs with that suggestion of lingering pain, his voice softened for the “we just wanted to help” lines. He had refined this role: the Guardian, bruised but noble, affronted by the very suggestion that he was anything but a shield against the dark. When Sarah asked about the hospital, he said an EMT at the precinct checked him out—no need to clog an emergency room. A nod to civic virtue. He agreed the cameras were out—tragically. He lost the temper he was supposed to hold when she pushed the coincidence of two separate devices failing at once. The flash of anger revealed something beneath the stage makeup. The jury flinched, then forgave him, then admired that forgiveness in themselves.

“The People rest,” Jensen said before lunch, already tasting the steak he’d brag about later. The jurors stared at the clock. The bailiff scratched a lottery ticket under the desk with his thumbnail.

Judge Reed checked the time. “We’ll break fifteen minutes. Defense will proceed at eleven forty-five. Ms. Jenkins, I hope you have something to present.”

As the judge left, Miller and Sullivan drifted past the defense table, muscles loose, mouths tight with amusement. Miller bent just enough to whisper something that smelled like cafeteria jokes. Sullivan added something that rhymed with smug. They expected flinching. They got none. The defendant stared forward. Sarah Jenkins looked down at a paper she did not need to read. She looked up into her client’s face and nearly took a step back.

The dull, beaten mask was gone. The eyes that met hers were cold and precise, focused not on survival but on strategy. The voice, when it came, was not the low mumble of a man trained to be small. It was clear, federal, and accustomed to rooms where men who hurt people learn they are not the only powerful ones around.

“Are you ready, Ms. Jenkins?” he asked.

Her shoulders squared as if a weight had been lifted. The nervous click of the pen stopped. “Yes, Director,” she said. “The assets are in place. U.S. Attorney’s Office is on standby. Evidence is queued.”

“Good,” he said. “Let’s begin.”

The courtroom filled again at eleven forty-five, the wood swallowing whispers. The jurors had idea fatigue. The reporters, who had expected a tidy midday conviction, refreshed their inboxes. The ADA pretended not to notice the swagger in his own posture.

“Defense?” Judge Reed said, finding her seat.

“Thank you, Your Honor.” Sarah’s voice belonged to a different woman. “Two preliminary motions before we call our witness.”

Jensen snapped upright. “Objection—motions time is past. Simple assault. We’ve all seen enough theater.”

“This simple assault,” Sarah said, “rests entirely on uncorroborated testimony from two officers whose only physical evidence is a bag that appeared after their ‘struggle’ broke both cameras. I seek permission to introduce newly declassified material cleared by the U.S. Attorney’s Office this morning.”

The air shifted. Jensen grabbed his phone, pretending he already knew. He didn’t. In the gallery, Miller and Sullivan stopped breathing like men in a movie who suddenly remember the twist.

“I’ll allow it,” Judge Reed said carefully. “But you’d better have more than a YouTube clip, Ms. Jenkins.”

“I do,” Sarah said. “And a second motion: to correct the record as to my client’s identity.”

Jensen almost laughed. “An alias? Your Honor, this is contempt.”

“Federally sanctioned undercover identity,” Sarah said, not looking at him. “Sealed by order of a U.S. District Court to protect an ongoing investigation. The target: Baltimore Police Department’s Fourteenth Precinct.”

This was the moment the air in Courtroom 3B collapsed into itself. It made a sound only dogs and guilty men hear. Miller’s face did something it had never practiced. Sullivan’s hands began to float without instructions.

“Your Honor,” Sarah continued, turning toward her client. “May I present Director Michael Thorne, Federal Bureau of Investigation.”

The man in scrubs stood, zipped down the neckline a few inches, revealing a white shirt collar that had no business inside county orange. The back doors opened as if on cue. Three people in dark suits with polished shoes and discreet earpieces walked in with the word federal stitched into their posture. They didn’t show badges. They didn’t need to. They took positions near the wall and looked like the room now belonged to a larger building in Washington, D.C.

Judge Reed worked her mouth, then found English. “Director… Thorne?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Sarah said. “Undercover as Michael Johnson. He consented to the arrest and allowed the booking to protect a six-month multi-agency corruption probe we code-named Operation Broken Shield.”

“Play the evidence,” Judge Reed said, voice suddenly very flat.

The clerk slotted the small encrypted drive. The monitors came alive with time stamps and a center-chest perspective that made the whole room lean forward. The sound was clean, the picture crisp. A patrol car slid into frame. Two officers stepped out. Their concern did not make it into the lens. Their words did.

“Good evening, officers,” said the calm voice from the microphone sewn inside the defendant’s jacket. “Is there a problem?”

“Yeah,” Miller replied, venting the word like steam. “You.”

There was a shove that made the camera jolt. The impact sound against brick didn’t need captions. The voice in the video kept repeating one sentence like a prayer white rooms teach: “I am not resisting.” The baton appeared half a beat before the hand that held it. Off to the left, Sullivan celebrated the loss of his body cam. “Mine too,” Miller answered, and the audio recorded a small, sharp crack that would turn a courtroom’s faith to salt. Then the hand to pocket, the extraction of a bag from the wrong place, the placement in the right one. A pat. A joke. A lie.

The screens went black. The courtroom didn’t.

There’s a silence jurors make when they’re rearranging their principles. You can hear it if you are the kind of person trained to listen to the end of a sentence, not just the beginning. It is slow and collective and very heavy.

Judge Reed removed her glasses with a careful slowness, the way surgeons handle scalpels. “Mr. Jensen,” she said without looking at him. “Stand up.”

He did. It took him two tries. She told him—in measured language that avoided profanity but not contempt—what it means to build a case on a wish. She told him that he had turned bias into procedure and expected applause. She told him the difference between not knowing and not wanting to know. The room did not clap when she was done. It would have been redundant.

She turned to the gallery. “Officers Miller. Sullivan.”

They did not stand. Two agents in dark suits invited them to. Another set of doors opened. This time there were more suits. One of them was an older man with the kind of charcoal suit that whispers power rather than shouting it. People who follow national news would later freeze the frame, circle his jawline, and caption the photo: Deputy Attorney General Robert Harrison, U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division.

“Your Honor,” Harrison said, voice that could sell calm to a hurricane. “Apologies for the interruption. This is no longer a state matter. The Department of Justice is assuming jurisdiction.”

He dismissed ADA Jensen from his job as if he were closing a tab on a browser. He announced a federal review of every single case those two officers had ever touched. He did it without raising his voice. Two agents moved beside Miller and Sullivan with the slow inevitability of a tide. “Stand,” one said. When Miller asked what for—last gasp of a man whose lungs are suddenly aware of air—the answer was a recitation of letters and numbers the city had reserved for organized crime: RICO among them; deprivation of rights under color of law; conspiracy; perjury; assault.

Sullivan’s knees loosened. An agent held him by the arm because he’d be no good to anyone crumpled on a courtroom floor. Miller’s face moved through a gallery of colors. He missed the window in which a man can salvage a sliver of dignity by walking upright. He tried to lunge past the agent’s hand and found out the hard way that the law can also be physical. He locked eyes with Thorne on the way out and found nothing there to hold onto.

“Please,” he said, sincerity finally discovering him. “Please. I—I have a family. I didn’t know who you were.”

Thorne stepped forward just enough to be heard without the microphone. “That,” he said evenly, “is the problem in one sentence.”

They led the uniforms out through a chorus of shutters. Cameras outside would catch the metal glint of the cuffs, the stare-into-the-middle distance men use when the future is being pried out of their hands, the way a city’s badge can look very small against a federal seal.

Inside, Judge Reed dismissed the charges against the man in scrubs whose name was and was not Michael. “With extreme prejudice,” she added, because the language has a phrase for fury when fury must wear robes. She apologized and meant it. She felt, you could see, that the stain had spread over fabric she believed herself to have kept clean.

Thorne nodded acceptance but not absolution. “What happened here today,” he said for the record and the ceiling microphones and the press who would pull the transcript, “happens every day. The difference is that the defendant today had a badge too, one bigger than theirs.”

Harrison briefed the room like a man reciting a grocery list written in statutes: the Fourteenth Precinct was already being dismantled; warrants ran like spiderwebs through city government; a councilman’s name had entered the chat; a captain was in custody. The marshals outside kept the cameras from swallowing the building whole.

Sarah Jenkins stood quietly and watched the institutional avalanche she had helped schedule. There was no victory dance. The win was large enough to be heavy. When Thorne thanked her, he did it like a colleague, not a client. She shook his hand the way lawyers do when they remember why they took this profession into their mouth and kept it there, even when it tasted like pennies.

They left the courtroom. The hallway hit them like weather. By the time the FBI Director reached the steps, the microphones were stacked like a fence. He faced them the way a man faces surf: feet planted, eyes forward, no wasted movement.

“Good afternoon,” he said. “Operation Broken Shield concluded this morning with twelve arrests, including nine active-duty officers of the Baltimore Police Department. Charges include racketeering, conspiracy, and deprivation of rights under color of law. Several weeks ago, while undercover, I was assaulted, framed, and booked by two of those officers. I allowed the process to continue because I wanted to see it as an ordinary citizen would.”

There is a sentence you can drop into an American city like a stone. It is not the name of an agency or a law. It is a description of what happens when power gets lazy: “They saw a man they chose not to value.” He said it, not with bitterness, but with a flatness that made it even harder to climb out from under.

Reporters asked the things we always ask when caught off guard by the obvious. What now? How far? How deep? Harrison handled the penalties. The minimums were stark. The words “no pension” hit the microphones like a clap. The phrase “federal penitentiary” moved through the crowd with the chill of a winter wind off the harbor. Jensen’s name came up. The Board. The review. The consequences that multiply once other people’s names are rewritten into the story.

Thorne ended the conference with a look that found one of the lenses and held it. “Let this be a message to anyone who wears a badge and mistakes it for permission. We are watching. To anyone who has built a career on the idea that some citizens count less than others: that career is over. My name is Michael Thorne. I am the Director of the FBI. And we are just getting started.”

He left the microphones to their echo. Inside the building, papers began to move in directions that foretold new lives: defense motions for men who had not been believed; internal memos with subject lines that included words like “audit” and “consent decree”; emails in which the words “best practices” finally meant prevention rather than cover.

If this were where the film ended, the audience would feel sated: wrongs righted, villains cuffed, institutions repented. But films, like closing arguments, lie by necessity. Real endings look like paperwork. They look like budgets. They look like reassignment lists and training modules and someone changing a patrol map that had been obeyed like scripture. They look like Sarah Jenkins leaving a courthouse and buying a coffee with a flicker in her chest that felt a lot like purpose. They look like a judge who, behind closed chambers, let her hand shake for a minute and then stopped it because the next calendar was already waiting.

That night, Thorne sat in a briefing room twelve floors up in a federal building with bad art on the walls and good sightlines on the street. His detail took up their quiet places. Harrison stood at the end of the table, sleeves unrolled, reading glasses on. Behind them, a screen filled with boxes: names, dates, lines between them. It looked like the math of an illness.

“Baltimore is the case study,” Harrison said. “We’ll use it when we go to the Hill. We’ll use it when we sit down with union leadership. We’ll use it when we talk to mayors who will call this an exception. We’ll show them body cam failure rates by precinct. We’ll show them who the cameras fail on. We’ll build a consent decree template that doesn’t let municipalities wriggle out after the cameras leave.”

“Policy is the slow justice,” Thorne said. “Slow is still justice if it moves.”

In a filing room two floors down, boxes with numbers on them were stacked for a convoy. Old cases were coming up for air. Somewhere in those files was the fingerprint of Officer Frank Miller’s favorite shrug, the one he gave to jurors who believed him because belief had been the default setting. Defense attorneys in a dozen neighborhoods began drafting motions that included the phrase “newly discovered evidence.” Prosecutors who had never learned to ask different questions opened their mouths and found some.

On the east side, a metal roll-up door rattled and stopped and then rattled again and then lifted. A small grocery bodega with scratches on the counter took down the sign that asked you to put your phone away when police entered. The owner had put it up after too many nights when “cooperation” sounded a lot like “tax.” He left the sign down and thought about adding a camera over the door. He decided to put one inside by the register too. Insurance, he told himself, but what he meant was memory.

At a kitchen table on the west side, a woman who had once stood for Miller in a courtroom because she didn’t know she had another choice watched the news. She watched the clip where the bag came out of the wrong pocket. She watched it three times. She called a number a cousin had texted her. The next morning she met with a law clinic intern with careful hair and too many notes. She told her story without apology. The intern wrote it down like an oath.

The pendulum didn’t swing. Pendulums are too neat. What happened was less a swing than a slow grind, a machine turning back on not because someone flipped a switch but because someone finally removed the sand. Men like Miller call that sand “paperwork.” People like Sarah call it “the job.” The machine is heavy. Heavy things move one inch at a time.

Weeks later, the Fourteenth Precinct looked like a place that had made eye contact with its reflection. A new captain arrived with a smile that did not make promises it couldn’t keep. The old coffee mug with the joke on it found the trash. A bulletin board that had once held a schedule for a side hustle became a bulletin board with the phone number for a counselor who, according to the rumors, had saved two marriages and a career. A body cam supplier sent a small army of technicians to retrain officers on simple things that should not have needed retraining. Someone noticed a line in the new policy: “Failure to activate without documented cause will be considered a reportable incident.” Someone else underlined it.

In the jail where Miller and Sullivan waited for federal transport, the televisions played a channel that favored local news. When the anchors said their names, inmates turned their heads because they liked irony when the universe delivered it warm. Sullivan had stopped staring at the wall long enough to feel the room staring back. Miller counted the faces of the men he had moved like furniture and did not give the number a sound. He told himself the system would catch him because he had been the system, and then he caught sight of the seal on the memo that arrived with his breakfast and it said United States in the place where he expected City of Baltimore. The difference between those two jurisdictions is a course he would have never chosen to take.

A month after the press conference, before dawn, a black SUV eased off I-395 and rolled east toward the Inner Harbor. In the back seat, Thorne watched the city blink awake. He had come to sit with Harrison and a federal monitor and a mayor who had inherited a weather report with the word “storm” written across it. The meeting would be long. It would be boring. It would be the point.

The monitor began with words no one likes to hear: “data,” “compliance,” “audit.” The mayor tried to skip to the part where someone shakes his hand with cameras. Harrison slowed him down. Thorne did the thing he is best at: he waited until the room decided to align, and then he moved it half an inch more. He left with a stack of agreements that felt like homework and a sense—small but stubborn—that homework gets you out of a grade you cannot afford to repeat.

Outside, on Pratt Street, a school bus coughed into life. Children climbed aboard with backpacks too big. A police cruiser rolled past in the bus’s reflection. The officer inside adjusted his body cam—not because someone told him to, but because he didn’t want to be the one in the report whose device mysteriously failed. That is not culture change in a press release. It is culture change in a shoulder shrug. Sometimes that is where revolutions begin.

Sarah Jenkins went back to Courtroom 3B two Tuesdays later on a case that wouldn’t be national news. Her client was not an undercover director. Her client had been arrested with one hand in his jacket and one hand up. This time, the cameras worked. This time, the ADA did not call a case “simple.” This time, the judge asked questions that smelled like fresh paint. Sarah argued with the steadiness of someone who had been asked whether she was ready and had said yes. She won on a motion she might have lost in a world where “his type” was still allowed to be a legal argument. She didn’t smile about it. She shook her client’s hand and told him to stay out of trouble and then stood outside the courthouse and let the winter air remind her that breath is a decision.

People asked Thorne why he hadn’t stopped it sooner—why he had let the cuffs go on, why he had allowed a booking, why he had walked into the courthouse in orange while a part of America still assigns meaning to color. He said the same thing each time, and meant it: “Because if I had stopped it, you would have told me it never happens.” Sometimes the only way to measure a system is from underneath it. The weight is the data. That day in Baltimore put a number to it. The number hurt. It needed to.

Months became a year. The DOJ consent decree moved from headlines to footnotes to foot patrol. A training module someone had rolled their eyes at became a thing an older sergeant quoted without irony. A younger officer pulled up to a stop and straightened his cam without thinking. A prosecutor asked a question that made her colleagues uncomfortable and then asked it again tomorrow. A judge used the phrase “with extreme prejudice” twice in a single week and slept better for it. A grandmother on a jury raised her hand during voir dire and asked about cameras like she was asking about seatbelts. She was selected. She took notes. She convinced a room.

Miller and Sullivan learned federal time with the quiet intensity of men who had believed rules were for other people. Their bravado curled up and went to sleep. Sometimes they woke in the night to the sound of a door they could not open. Somewhere, a councilman practiced a version of contrition in a mirror and hired a lawyer who reminded him that sentences can be both short and long. Jensen discovered that disbarment letters are printed on nice paper. They feel heavier than their weight.

On the anniversary of the arrests, Thorne walked the long corridor on the seventh floor of the J. Edgar Hoover Building toward a conference room where someone had placed a cake and someone else had arranged a PowerPoint slide. He stopped at the glass and looked at the reflection of a man who had been a story. He did what men in his position rarely do: he let the humility in. “Not over,” he said to no one particular. “Just started.” His assistant—a woman who had learned his calendar the way a pilot learns alarms—handed him a folder. Inside were numbers from another city that looked too much like Baltimore’s old numbers. He added a page to the front that said: “Broken Shield – Phase II.” He went into the room. People clapped. He told them to sit. He turned to the slides and began again.

In Baltimore, Courtroom 3B carried on. Cases. Tears. Small mercies. A juror laughed at the wrong moment and then pressed her lips together and didn’t do it again. A young ADA took notes in a different way. A sign posted at the clerk’s window read, “All parties are reminded: recorders are always in order.” The ink was fresh. The policy was old, but the enforcement felt new. A boy on a field trip visited the gallery, stared at the judge, and whispered to his teacher that the room felt “like a place where words stand up straight.” The teacher wrote that down to remember on days when nothing stood up at all.

It would be a lie to say Baltimore was fixed. Cities don’t break that neatly and they don’t heal that way either. But a thing had happened here that is rare enough to name: a system had looked at itself without a filter. The picture was not pretty. They didn’t delete it. They printed it out and taped it above a desk where policy gets written, so that every sentence drafted had to glance up at the image and decide not to become it again.

As for the man in the scrubs, the one with the county tag and the federal eyes, he went back to the work. He went back because there were other rooms and other lights and other names on other dockets. He went back because the work is not the press conference and it is not the cuffs. The work is the meeting after the meeting when you ask the unpopular question and you do not allow the comfortable answer. The work is telling the truth in the place where truth is a line item. The work is slow. It is still justice if it moves.

On certain nights when the schedule allowed it, Thorne would walk without the motorcade. He would take the long way along the water, a cap down low, a scarf up high, anonymity purchased for an hour with the currency of posture. He would pass a bodega with a camera over the door and a man behind the counter who looked up and nodded the universal nod that says I see you. He would pass a patrol car and watch a hand adjust a camera without anyone telling it to. He would pass a bus stop where a kid in a hoodie practiced a presentation out loud, trying to get the first joke right. He would keep walking until the city gave him that thing it gives to people who listen: the sense that you are standing inside something larger than your name.

The city’s lights burned too bright, washing out the stars and making their own. He let them. Some stories don’t need constellations. They need a bench, a gavel that remembers when to land, a camera that does not break, a pen that does not run out of ink, and a man in orange who stands up and becomes himself in front of everyone.

Karma does not carry a badge. People do. On that winter morning in Maryland, accountability wore one. It fit. It still does.