The sprinklers hissed to life across a quiet Texas cul-de-sac, throwing arcs of silver water into the humid morning air. The flag on the porch barely stirred, and somewhere nearby, a dog barked twice before falling silent. It was an ordinary summer morning in suburban Houston, Texas—the kind of morning that belonged to coffee pots, cereal bowls, and the soft hum of air-conditioners. Nothing about it warned that, within a few hours, the name Andrea Yates would echo across every news network in the United States.

Before the sirens and the headlines, before the courtroom sketches and the televised debates about insanity and justice, there was simply a girl from Hallsville, a small town tucked inside the heart of East Texas. Andrea Pia Kennedy was born there on July 2, 1964, the youngest of five children in a working-class family that prized discipline over display. Her father, Andrew, taught auto mechanics at the local high school. The smell of motor oil clung to his shirts; his hands were calloused from decades of labor. Her mother, Jutta (Uda), kept the household afloat with thrift, patience, and the kind of stoic pride that first-generation immigrants carried like armor.

The Kennedys were not wealthy, but they were orderly. Faith, work, and responsibility built the scaffolding of their days. In that neat, modest home, Andrea learned that silence was a virtue and perfection a duty. Being the youngest meant watching more than talking. Her older siblings filled the air with opinions; she filled notebooks. Teachers remembered her as bright and serious, almost unnervingly mature for her age. She was the student who handed in essays two days early and then fretted over the margins not being straight enough.

In classrooms where louder personalities grabbed attention, Andrea’s focus was a kind of rebellion of its own. She loved mathematics and science, subjects that offered clean answers and measurable truths. If she scored a 98 on a test, she worried about the missing two points more than the grade itself. Beneath the straight-A record ran a quiet current of anxiety—a need to be flawless that, with time, would become a trap.

Outside school, her escape was the swimming pool. The lane lines, the rhythm of arms slicing water, the smell of chlorine—everything about swimming appealed to her disciplined nature. Coaches described her as relentless: she pushed herself until her shoulders burned, until the stopwatch showed improvement. In those hours, Andrea seemed to shed the perfectionist student and become someone freer, stronger, almost serene.

By the time she reached high school, Andrea had built a résumé that would have made any parent proud. She was active in the National Honor Society, captained the swim team, and graduated in 1982 as valedictorian. Friends recalled her as the “ideal daughter”—polite, focused, responsible, maybe a little too self-contained. “She was the kind of girl,” one classmate later said, “who made you believe she’d never get a parking ticket.”

After graduation, she moved two hundred miles south to Houston, enrolling in the University of Texas School of Nursing. It was a pragmatic dream. Nursing fit her perfectly: a profession that balanced compassion with precision, requiring both heart and discipline. Andrea thrived in that environment. She memorized procedures with photographic accuracy, absorbed medical terminology like a new language, and learned how to stay calm amid the whirl of hospital emergencies.

Upon earning her degree, she joined the staff at MD Anderson Cancer Center, one of the most prestigious hospitals in the United States. There, surrounded by the constant fight against disease, Andrea proved herself capable, dependable, and gentle with patients. Her colleagues saw a woman who never cut corners, who followed protocols to the letter, who always volunteered for the difficult shifts. Yet outside work, she remained almost painfully private.

She didn’t drink much, didn’t party, rarely dated. While other nurses decompressed at bars or beach houses, Andrea spent her evenings alone in a small apartment, reading medical journals or jogging through quiet Houston neighborhoods. “She lived like a ghost,” one coworker later said—not unkindly, but truthfully. It wasn’t loneliness exactly; it was control.

By her mid-twenties, Andrea had what most would call stability. She had a respected job, a clean apartment, a reputation for reliability. There were no signs—none—that her life would one day unravel in front of cameras and court reporters. But in 1989, at age twenty-five, a meeting changed everything.

He was Russell “Rusty” Yates, an Auburn-educated engineer working at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Where Andrea was reserved, Rusty was open, ambitious, confident. He spoke quickly, laughed easily, and radiated the certainty of a man with plans—plans for a career, for faith, for family. They met through mutual friends and, as people later described it, “clicked immediately.”

They talked about work, about purpose, about faith. Both came from religious households that prized devotion and order. Both wanted a home filled with children. To outsiders, they looked like the perfect match: the meticulous nurse and the driven engineer, two people building their lives around discipline and belief.

From the beginning, Rusty talked about wanting a large family. He admired a preacher named Michael Woroniecki, who promoted a minimalist, back-to-basics form of Christianity—rejecting materialism, embracing simplicity, and raising many children as proof of divine obedience. Andrea listened, nodded, and accepted. She loved children. She loved structure. And she wanted to be the kind of wife who supported her husband’s calling.

They married in 1993, a modest ceremony without excess or spectacle. At first, their life was textbook American: small apartment, two steady incomes, Sunday church, plans for a house. But soon, under Woroniecki’s influence, Rusty began pushing for a more radical simplicity. He sold off belongings, preached about spiritual purity, and suggested they downsize further. Andrea followed his lead, and before long, the couple was living first in a compact trailer, then in a converted bus—a mobile experiment in faith over comfort.

It was the kind of choice that looked noble on paper, but in practice it meant isolation. Andrea, who already leaned toward introversion, now found herself cut off from coworkers and friends. The outside world shrank to the size of a kitchen table. Within that confined space, the boundaries between devotion and self-denial began to blur.

In 1994, Andrea gave birth to their first child, Noah. She was twenty-nine. Holding him, she felt the surge of purpose she had always imagined. “It was like everything finally made sense,” she would later recall. But alongside joy came an invisible weight. Perfectionism, once her armor, became her torment. She measured herself against impossible standards of motherhood, terrified of failing at something so sacred. Every cry felt like an accusation. Every sleepless night fed the whisper that she wasn’t enough.

The family grew quickly: John in 1995, Paul in 1997, Luke in 1999. Each birth brought happiness and exhaustion in equal measure. The converted bus that once symbolized faith now felt claustrophobic, packed with toys and laundry and the endless noise of small children. Rusty worked long hours at NASA, convinced that providing financially was his greatest duty. Andrea, alone for most of each day, sank deeper into anxiety.

After Luke’s birth, her mood darkened. Friends noticed she seemed thinner, quieter, her smile forced. She spoke of feeling “tired all the time,” of guilt she couldn’t explain. In 1999, the signs sharpened into crisis. One afternoon, overwhelmed and hopeless, Andrea attempted to end her life with an overdose. She survived, was hospitalized, and placed on antidepressants. Doctors urged ongoing treatment. For a while, she seemed better. Then the spiral returned.

That same year, she experienced another severe episode, threatening to harm herself with a knife. Once again, she was hospitalized and diagnosed with severe postpartum depression and psychosis—conditions that can warp perception, trigger hallucinations, and blur reality. During her stay, Andrea confided terrifying thoughts: that Satan was inside her, that television sets were sending her messages, that she might harm her children to protect them from damnation.

Her doctors warned Rusty in explicit terms: another pregnancy could be dangerous, even deadly. They advised against expanding the family, stressing that each postpartum period deepened her psychosis. But faith and idealism overrode medical caution. The Yateses believed they could manage; that prayer, love, and discipline would keep darkness at bay.

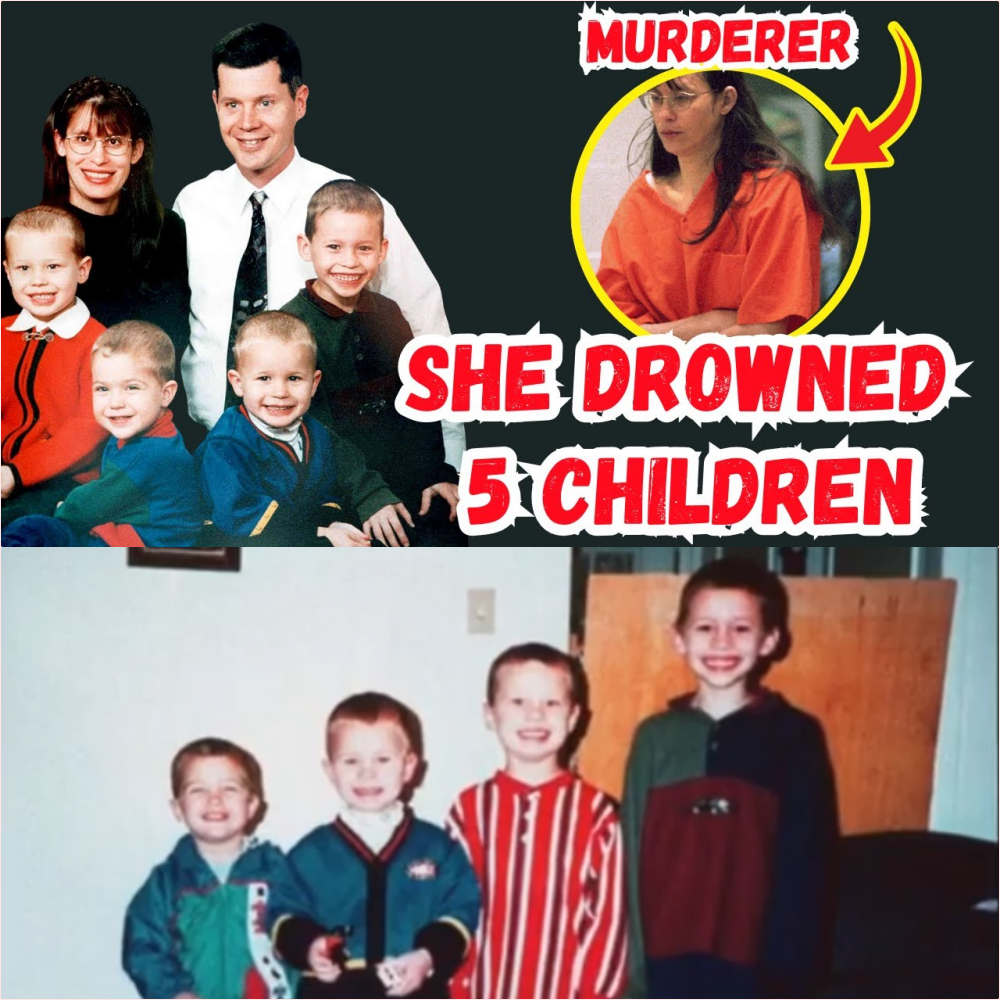

On November 30, 2000, Andrea gave birth to their fifth child—a daughter, Mary. For the first time, she had a girl. Photographs from those months show her smiling, eyes bright yet distant, as though joy and dread shared the same face. Friends said she glowed when holding Mary. But inside, she knew something was unraveling.

By early 2001, her mental health was deteriorating fast. She ate little, slept less, stopped speaking for long stretches. Sometimes she sat motionless, staring into space for hours. When she did talk, it was about being “a bad mother,” about “failing the children.” In March, she made another attempt on her own life—submerging herself in the bathtub before panic forced her to stop.

Again she was hospitalized, treated with antipsychotic medications including Haldol, a powerful drug that briefly restored her clarity. But every improvement was temporary. Each discharge from the hospital returned her to the same environment: five children under seven, a husband gone most of the day, and the suffocating isolation of a home she could not escape.

One psychiatrist explicitly wrote that Andrea should never be left alone with the children. It was a warning carved in fluorescent ink—but in the fog of daily survival, it faded. Rusty, ever optimistic, believed she was recovering. He encouraged her to resume “normal life,” convinced that routine would heal her.

Compounding her fragility were the continuing letters and sermons from Woroniecki, the preacher whose austere teachings had shaped the Yates household. His words about sin, damnation, and purity now struck Andrea not as metaphor but as commandment. She began to interpret them literally, believing that her failures as a mother were endangering her children’s souls.

By May 2001, she was unraveling completely. She tore at her scalp, pulled out clumps of hair, refused food, and lapsed into silence. Some days she seemed catatonic; other days, haunted. Rusty urged positivity—“You’ll be fine, Andrea, just think good thoughts”—but optimism was no match for psychosis. On May 3, she was admitted to the Devereux Treatment Network, where psychiatrist Dr. Mohammad Saeed noted her severe depression and auditory hallucinations. Andrea told him she believed Satan lived inside her, that she was evil, unfit to mother her children.

She improved slightly under medication and was sent home—too soon. Within two weeks she relapsed, then cycled through another brief hospitalization. Each time, her improvement was read as stability rather than reprieve. Friends pleaded with Rusty to keep her in care longer. Doctors cautioned restraint. Still, by June 2001, she was once again home alone for hours each day, surrounded by five small children and a storm inside her mind.

In the weeks before tragedy, Andrea’s thoughts turned apocalyptic. She told her mother she couldn’t handle the children. She told doctors she had visions of harm. She believed the devil was whispering to her, that her children were marked for eternal suffering. Saving them—she thought—might mean removing them from this world.

Two days before the event, on June 18, Rusty came home to find Andrea filling the bathtub. “Just getting ready to bathe the kids,” she said. He thought nothing of it. The next day, she visited her parents’ house. Her mother begged her to stay a few days for rest. Andrea promised she would. But by then, her decision was already set in the delusional architecture of her illness: she would “save” the children.

Morning broke over Clear Lake like a promise, the sun climbing clean and high over roofs with neatly trimmed eaves, over mailboxes painted with cardinals and NFL logos, over driveways chalked with hopscotch squares half-faded by last night’s sprinkler cycle. Rusty Yates kissed his wife goodbye, grabbed his badge, and steered the sedan toward NASA’s Johnson Space Center, where checklists and redundancies ruled the day. Inside the small house he left behind, routine moved forward on soft feet: cereal bowls, cartoons, the chaos of five small voices weaving in and out of each other. On paper, it was the safest picture America knew how to draw. In reality, it was a mind on the edge, trying to hold the line against a storm no one else could see.

Andrea moved through the rooms with the deliberate quiet of someone following instructions only she could hear. Psychosis is not a thunderclap; it’s a radio station that seems to grow clearer the more the world begs you to turn the dial. She fed the baby, straightened a blanket, picked up a toy car, and then, as if pulled by a tide, walked to the bathroom and turned the faucet. Water struck porcelain—an ordinary sound in an ordinary Texas morning. But nothing about this moment was ordinary, and nothing about what followed can be narrated without care. So we will say this, and only this: in a series of actions bound by illness and delusion, Andrea brought her children beyond harm’s reach as she understood it in that fractured hour, one by one, the oldest last, moving with a focus that would later confound even those paid to understand such things.

Silence followed—the kind of silence that sits on your chest. The clock over the stove ticked. The air-conditioner cycled on. Outside, a UPS truck rumbled past and left a package on a neighbor’s porch. Somewhere two blocks over, a lawn crew pulled a cord and a mower coughed to life. The world moved, unknowing.

Andrea picked up the phone and dialed 911. Her voice, when it came, was flat, almost businesslike. The dispatcher’s questions tried to pull shape from the shapeless. Andrea answered with simple sentences, not avoiding, not embellishing, just stating. When she hung up, she called Rusty. “You need to come home,” she said. “It’s time.” He asked what was wrong. She said something about the children. He left his desk, keys jingling, a man in a NASA polo walking too fast down a hallway lined with mission posters about trajectories and safe returns.

Police arrived first, then paramedics. The curb outside the Yates house filled with flashing lights, blue-red-blue-red pulsing against siding and shutters. Neighbors drifted onto lawns, drawn by the choreography suburbia knows by heart: sirens, yellow tape, a growing cluster of uniforms. They peered from behind gable windows and hedges, trying to see and trying not to see. Harris County officers stepped inside, and in moments the small, tidy house became an official scene—measured, documented, mapped. What they found would follow them for years.

Andrea didn’t run. She didn’t shout. She sat quietly and admitted what she’d done in the only framework available to her: she believed she had “saved” the children from a darkness that had been whispering for months. The officers spoke to her gently, like people stepping across cracked ice. They cuffed her because that is what the law requires, and led her out while cameras began to gather. Someone threw a sweatshirt over her shoulders against the June heat; the day had turned blistering, like it does in Houston when noon draws near.

By the time Rusty’s sedan turned onto the street, the cul-de-sac looked like a news graphic: patrol cars nosed together, the ambulance angled across the curb, a tangle of cables from the first TV van to arrive. Officers stopped him at the tape. Whatever sentence they used, it folded his world in half. People saw the moment from a distance: a man rocked on his feet, then steadied; neighbors put hands to mouths; reporters murmured names and dates into phones. Houston—and soon the entire United States—began to learn the details the way America always does: in bulletins first, then chyrons, then trembling interviews on the six o’clock news.

The next hours were all procedure. Andrea was transported under observation to a mental health unit for evaluation. Nurses assessed her affect: blunted. Thought content: delusional. Insight: impaired. Risk: ongoing. She was placed on watch. Blood draws. Vitals. A quiet room. A psychiatrist began the first of many interviews, moving carefully, building a timeline from fragments. Andrea spoke calmly about voices, signs, and the certainty of having failed as a mother. She used religious language—not as ornament, but as architecture. To her, this was duty completed under orders no one else could hear.

Meanwhile, Harris County prosecutors and investigators began their parallel work: assembling a case by the book. The law is a machine designed to run on observable facts. It does not diagnose; it weighs. They inventoried the house, reviewed the 911 recording, took statements from neighbors, reached out to family. A decision had to be made quickly: what charges, under what theory, with what potential penalties. Texas law offered the harshest path; public sorrow, confused and boiling, gave permission to walk it. The phrase “capital murder” appeared in print before sundown.

The Yates home remained under tape through the afternoon. The street that had once hosted Halloween parades and garage sales now carried satellite trucks and tripods. Producers settled on a frame—porch, flag, police tape—and locked the shot. Neighbors cried on camera. Friends from church spoke of a mother who adored her children, who baked, who read Bible stories, who seemed to be fighting something invisible for years. Reporters asked about warning signs, about medical care, about faith. It was impossible to get the tone right. Any sentence too sharp felt cruel. Any sentence too soft felt dishonest.

Night fell and with it came the first national segments. In New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, anchors read from teleprompters about suburban Houston and a mother of five. The story had every element the American media machine responds to: a quiet neighborhood, a household of faith, a connection to NASA, and an act so devastating that people stared at their televisions as if staring would produce an explanation. Words like “postpartum,” “psychosis,” and “insanity defense” began their march from medical journals into living rooms.

Inside Harris County Jail, Andrea moved into the limbo of pretrial confinement. She was kept on suicide watch. Medication resumed, then adjusted. Psychiatrists noted how quickly her mind responded: the fog lifting just enough to reveal the canyon’s edge. That is one of the merciless truths of treatment: clarity returns before comfort. She began to understand, piece by piece, what had happened. She asked for a Bible. She spoke to her lawyers in that same steady voice, answering questions about pregnancies, hospitalizations, and the mounting fear that had followed her from the Devereux ward back into the busyness of daily life.

The law appointed a defense attorney, and then a second, men known not for theatrics but for patience. They built a file the way old-school reporters build a story—from documents outward. Hospital records. Physician notes. Pharmacy logs. The written admonition—never leave her alone with the children—underlined twice in a doctor’s hand. Friends’ emails about Andrea’s blank stares and whispered dread. Sermons and letters that framed suffering as a test and simplicity as armor. The defense’s thesis was not complicated: Andrea was severely ill. On that morning, she moved inside a reality that did not match the one shared by the rest of us. The legal phrase they would reach for—“not guilty by reason of insanity”—was old and narrow, but it was the only phrase the system offered to fit a mind unmoored.

Across the square, the District Attorney’s office crafted a narrative of its own. They emphasized sequence and deliberation: the faucet running, the order of actions, the 911 call, the statement to Rusty. To the prosecution, these were signposts of awareness, proof that Andrea’s mind, however troubled, still grasped what she was doing and that it was wrong under law. The state announced it would seek the maximum penalty. In Texas, those words landed with the weight of decades. The community’s sorrow, still raw, gave the announcement a soundtrack of nods.

In the weeks that followed, talk shows did what they do—turned complexity into segments and sorrow into ratings. Some guests shouted; others trembled. A psychiatrist with credible credentials explained how postpartum psychosis is not a mood but a break—a rare, acute rupture that can saturate perception with delusion and command-like thoughts. A pastor talked about grace. A former prosecutor talked about deterrence. A neighbor held up a photo from a birthday party: cake, balloons, a mother leaning in to help a child blow out candles. “This is who she was,” the neighbor said, voice shaking. “Or at least, this is who we thought she was.”

Rusty, for his part, moved through those weeks with a look people recognized: the blankness of a man whose internal systems were all rerouting at once. He attended arrangements no parent should have to contemplate. He answered investigators’ questions. He faced cameras he didn’t want to face. He defended Andrea’s goodness while being accused—by strangers with strong opinions—of blindness, of negligence, of driving his family toward an ideal too unforgiving to survive. He insisted she was a loving mother undone by an illness neither of them truly understood. To some, that sounded like grace. To others, it sounded like excuse.

The first court appearances were short and procedural—dates set, motions filed, the machinery engaged. Andrea appeared in a light-colored jail uniform, hair pulled back, expression subdued. When the judge asked if she understood the charges, she said yes. When asked to confirm her name, she did, voice barely above a whisper. Reporters sketched furiously, the way they’ve always done, as if capturing the angle of a mouth might reveal motive.

Back in the hospital wings of the jail, medication did its slow arithmetic. Andrea’s delusions receded to the margins; reality moved forward like a tide. She began to speak more linearly about the months prior—about the Devereux admissions, about Haldol, about days when she could not make herself eat or speak, about nights when she felt the house tilt toward darkness. She spoke about faith not as a weapon but as a language she had used to describe the indescribable. The doctors recorded, adjusted, recorded again.

And everywhere, America kept watching. The story had become a mirror people could not stop looking into: suburban normalcy pretending to be a fortress, mental illness misunderstood until the worst, the thin line between spiritual discipline and isolation, the way a warning written on a chart can be lost in the clatter of everyday life. In living rooms from Phoenix to Philadelphia, viewers asked questions out loud to no one: How did this happen? Who could have stopped it? What does justice even look like here? The answers were not on TV. They were tangled in files and testimony the public hadn’t seen yet.

In time, the children were laid to rest—five small names carved into stone in a Houston cemetery, where the cicadas buzz loud in the heat and the summer storms come fast. The funerals were private, as they should have been. Outside the gates, cameras waited anyway, because that is what cameras do. People left flowers and small toys, notes folded into quarters and tucked beneath pebbles. The ritual was not for explanation; it was for endurance.

When the indictment came, it landed with the formality of a stamp on thick paper. The state would argue its case in full. The defense would present the map of a mind undone. Andrea Yates would stand trial in Harris County, a geographic fact that placed this tragedy squarely in the American legal story—a story about culpability, capacity, mercy, and the limits of language. The calendar filled with dates. Experts were retained. Jurors would be summoned from their routines—Kroger cashiers, refinery techs, elementary school librarians—and asked to sit in judgment over the hardest questions the law knows how to ask.

Before the trial, Andrea remained under careful supervision. Some days she knitted. Some days she read the Psalms aloud in a voice too soft to carry. Some days she sat in the dayroom window and watched buses drift down the freeway toward Galveston, small as toys. Staff noted that she apologized often—not performatively, but as a reflex, as if every breath required permission. Clarity had returned, but comfort had not. That is the part television rarely shows.

By late winter, the courthouse routines had grown familiar to everyone involved: the security line, the hum of the escalators, the press pen filling before dawn. On opening day, Houston’s sky was the particular shade of blue that follows a cold front. Families of the victim-children took their seats. Rusty sat stiffly, jaw working. The defense placed a stack of medical records on the table—a paper mountain that, if read closely, told a story of warnings issued and moments missed. The prosecution arranged photos and a timeline, clean and spare, the kind of exhibit that looks persuasive before anyone speaks.

And then the doors closed on the outside world, at least metaphorically. A courtroom is a theater with rules: evidence in, speculation out; facts established, opinions quarantined. But everyone knew the theater would leak—into living rooms, onto radio call-in shows, through headlines that preferred thunder to rain. America—from Boston to Bakersfield—would weigh in with the easy certainty of distance. The people in the room would have to live with the weight of nearness.

This is where Part 2 leaves us: on the threshold of the trial, with the streets of Houston, Texas still glinting from last night’s sprinklers, with cameras warming in the morning sun, with a prosecutor ready to argue intent and a defense ready to map illness, with a husband who has lost everything and refuses to hate, with a mother who has regained just enough lucidity to understand the ruin. The next act will not promise catharsis. It will offer only process—jury selection, testimony, cross-exams, a verdict that can carry truth and still fail to heal.

Before we step across that threshold, one last image to keep in view, because stories like this need anchors: a small kitchen in Texas, a grocery list still magneted to the fridge, apples and milk and detergent written in a careful hand. Life had every intention of continuing. It is the extraordinary cruelty of certain illnesses—and the ordinary failures of vigilance—that it didn’t.