It began with a breath of cold air, the kind that stings the lungs and makes daylight feel unreal. Elizabeth Fritzl had not seen the sun in twenty-four years when her feet touched the outside world again. The hospital doors slid open, and she stepped into a light so sharp it felt like a blade. To the doctors gathered around her, she looked like someone emerging from the ruins of another century. To America—where her story would soon explode across every news network from New York to Los Angeles—it looked like the resurrection of someone who had been declared lost long ago.

But before the headlines, before the shockwaves, before the world tried to understand how such darkness could hide in such an ordinary town, there was a house. A pale yellow house with blue shutters on a quiet street in Amstetten, Austria—so peaceful it could have been mistaken for a postcard. The kind of house American tourists might pass while admiring the charm of Europe. Nothing about it looked threatening, nothing suggested secrets buried under concrete and steel. The windows were trimmed with flowers each summer, the curtains drawn neatly in winter. Everything tidy. Everything correct.

And beneath that perfection, one of the most haunting stories of modern true crime was unfolding—one that would later fascinate American talk shows, documentary producers, late-night hosts, and true-crime fans for years. Because it wasn’t just a crime; it was a hidden world, a parallel universe carved out beneath a suburban home by a man who looked like everyone else.

Before 2008, the story was not known in Austria, or Europe, or anywhere. Not in the United States, where it would eventually dominate prime-time specials. Not even in the small neighborhood where a father lived quietly above the daughter he kept beneath his feet.

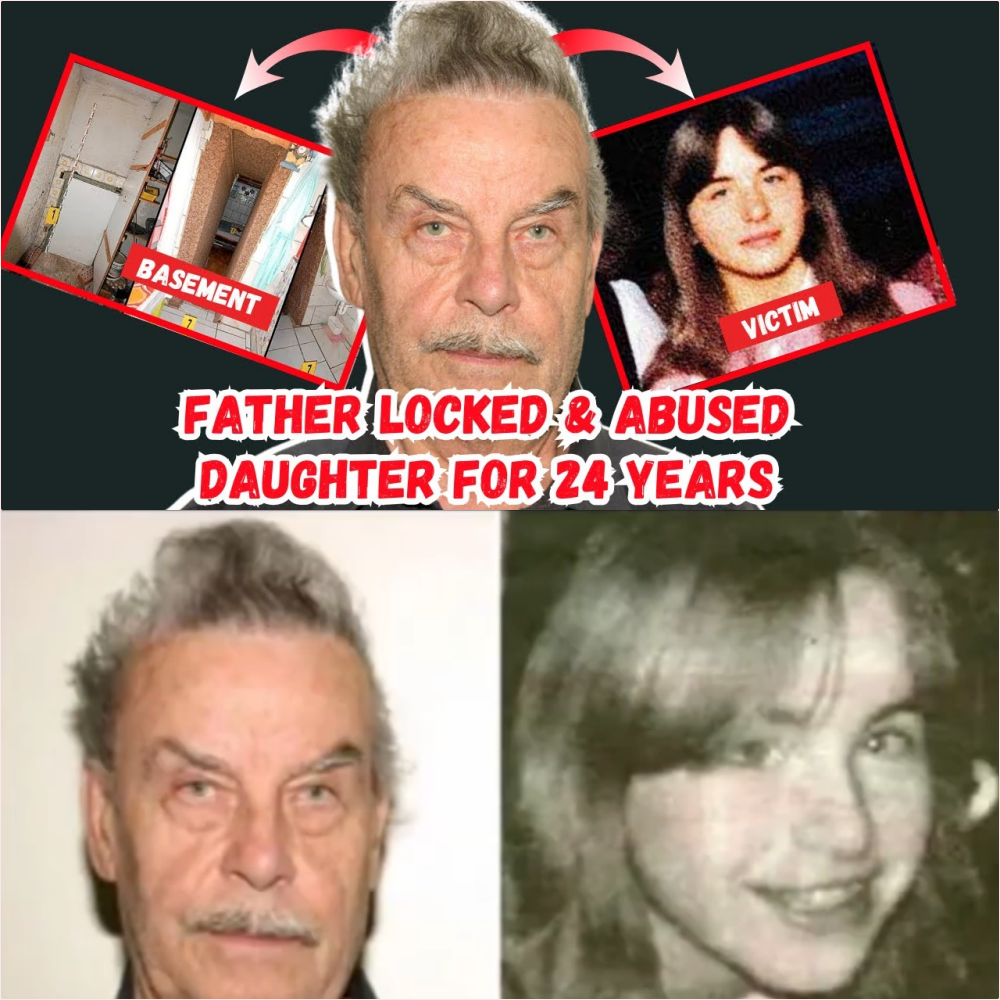

Her name was Elisabeth Fritzl.

She vanished at eighteen.

And for the next two dozen years, she existed only underground.

She did not begin life in darkness. Elisabeth was born in 1966, the fourth of seven children raised by Josef and Rosemary Fritzl. She was shy, gentle, the kind of girl who preferred reading under a blanket to running through the neighborhood. She loved animals and drawing and the soft comfort of quiet places. But the house she grew up in was not warm. Her father ruled with a rigid hand—strict, quick to anger, and obsessed with obedience.

Out in the world, he projected steadiness. He was an engineer, a man who built things, applied for permits, read the newspaper with disciplined precision. To neighbors he was quiet, serious, a little cold, but respectable in the way older European men often seem. No one saw the shadows forming behind the façade.

Inside the home, his word was absolute. The Fritzl children feared him, but Elisabeth feared him differently. His gaze lingered too long, his corrections felt like warnings, and even as a young teenager, she sensed that the danger around her didn’t come from outside the family—it came from him. She tried to run away once, then again. But she was young, unsure, and eventually she came back.

In 1984, days before her eighteenth birthday, she told her mother she had an interview lined up for a job. She promised to call. She walked out the door—and disappeared.

The search that followed was earnest but short-lived. Flyers were printed, friends questioned, but weeks later Josef arrived at the police station with a handwritten letter. In it, Elisabeth claimed she had joined a religious group, a traveling collective, and no longer wished to be contacted. Austrian police accepted it. They had seen teenagers leave home before. They closed the case.

What they did not know—what no one in the world imagined—was that Elisabeth was already beneath the yellow house. Josef had lured her into the basement under the pretense of helping him, then closed the heavy door behind her. When she woke, the walls were concrete, the air stale, the light dim. There was no window. No sound from the world above. No way out.

Josef had spent years preparing the space. He told neighbors and officials he needed a protected shelter—Europe still carried Cold War anxieties, so the idea didn’t seem unusual. He filed the paperwork, dug deep, reinforced walls, installed layers of doors. But beneath each justification was a darker intention. He wasn’t building a shelter. He was building control.

To reach the final chamber where Elisabeth would live, one passed through a steel door, a narrow hallway, a hidden panel disguised behind a shelf, a coded lock, and finally a tunnel so small it required crawling. At the end was a cramped bunker barely tall enough for her to stand upright. This was where she would spend half her life.

It began with fear. She called out until her voice cracked, but no one heard. Her father came and went with supplies, instructions, warnings. He told her that the world outside was dangerous, that no one would believe her if she tried to escape, that the room could flood or fill with fumes if she disobeyed. He controlled the lights, the air, the food, the sound. He controlled everything.

Time blurred. Hours melted into days, then weeks, then months. Elisabeth tried to mark the passing of time on scraps of paper until days repeated too evenly to track. The bunker hummed with pipes overhead, her only reminder a world existed beyond the concrete.

Then her body changed. She became pregnant.

There was no doctor. No nurse. No comfort. Just a concrete floor, rough blankets, and her father’s heavy presence. It was not an event as much as a trial of endurance. She endured silently, biting her lip until it bled, clutching the cold ground, trying to push through the unimaginable with no support other than her will to survive.

Her first child, a girl she named Kirsten, was born into that darkness. The sound of the baby’s first cry echoed off the walls like an alarm that no one could hear. Elisabeth held her newborn and realized that the bunker was no longer her prison alone—it had become a world for someone else too.

The years that followed were a cycle of survival. More children came: Stefan, then Felix. Three of Elisabeth’s seven children grew up entirely underground. Three others were taken aboveground by Josef, who staged their arrival as abandoned infants at his doorstep—each accompanied by a note supposedly from Elisabeth saying she couldn’t raise them. His wife, Rosemary, accepted the story. She’d been told for years that Elisabeth had joined a remote group; why wouldn’t she also send children she couldn’t care for?

So above the bunker lived Lisa, Monica, and Alexander—children who attended school, breathed fresh air, and played in the yard, never knowing they had siblings below. It was a dual reality, two parallel worlds spinning in the same house without ever touching.

The three below lived with rhythms dictated by survival. The television became their only window to the world. Old tapes and children’s shows flickered like glimpses of a life they couldn’t touch. Elisabeth taught them everything she could—reading, math, stories about mountains and oceans. She described the sky until it felt almost real. She created games, routines, tiny celebrations inside that airless space.

But the bunker had limits. The children’s bodies were pale, their lungs fragile, their eyes sensitive to light they had never seen. The absence of fresh air left them often sick. The dampness seeped into their bones.

Yet life continued—quietly, secretly, beneath the floorboards of a perfectly ordinary Austrian home.

Outside, Josef lived a double life with remarkable ease. He shopped, paid bills, took vacations with his wife, entertained neighbors with gruff small talk. He walked past the police station without a flicker of guilt. He was a retiree, a handyman, the kind of older man people forgot to notice. Nothing about him warned the world that he spent nights in a hidden underworld of his own making.

The illusion lasted until 2008.

It started with Kirsten. By then she was nineteen, and her health had always been fragile. But one day she collapsed. Her body seized and shivered uncontrollably. She became unresponsive. Elisabeth panicked. She begged Josef to help. For the first time in twenty-four years, he hesitated. His carefully insulated world was collapsing inside a single desperate moment.

He took Kirsten to the hospital.

Doctors were stunned. The girl arrived with no identification, no medical history, and symptoms that made no sense for someone her age. She was malnourished, pale to a degree they’d only seen in patients deprived of sunlight for years. Her teeth were underdeveloped; her immune system seemed unfamiliar with the outside world. The note Josef offered—signed by “Elisabeth”—only deepened suspicion.

The hospital notified authorities. The Austrian press quickly caught wind of an unidentified girl in critical condition. The story began spreading, eventually catching the curiosity of international media as well—including outlets in the United States, where true-crime audiences were always drawn to mysteries involving vanished children.

Police made public appeals for the “mother” to come forward.

Down in the bunker, Elisabeth saw the news on the small television. For the first time in almost a quarter-century, the world was calling for her.

She made a decision. She told Josef:

“If you want to save her, let me go with you.”

Surprisingly, he agreed.

On April 26, 2008, Elisabeth stepped outside for the first time in 8,516 days.

When she entered the hospital, officers were already watching. They separated her from Josef and quietly reassured her that she was safe. One female officer told her gently, “You don’t have to explain anything right away.” And something inside Elisabeth—held tightly for decades—finally cracked open.

Over the next two hours, she told them everything.

The cellar.

The years.

The pregnancies.

The two worlds inside one house.

The threats.

The fear.

The children.

The silence.

It was a story so overwhelming that the officers later said it felt like a script from a horror film—except the woman sitting in front of them had lived every minute of it.

Josef Fritzl was arrested the same day. He did not deny much. When asked why he had done it, his explanation was chilling in its emptiness: a vague justification that revealed nothing about the truth of his motivations.

By the next morning, the story erupted across Europe and quickly reached the United States, where networks scrambled to cover the case. Americans compared it to their own infamous true-crime tragedies, debating how such evil could hide behind the façade of a normal family home. The small Austrian street became a global spectacle.

Outside the yellow house, crowds formed—some carrying candles, others shouting in anger. Reporters camped on the sidewalks. Photographers captured the blue shutters that had concealed the unimaginable.

Inside the hospital, Elisabeth stayed by Kirsten’s bedside. She held her daughter’s hand and whispered the same stories she had whispered in the bunker. In another room, Stefan and Felix were seeing daylight for the first time. Doctors gave them sunglasses to protect their unaccustomed eyes. Even the sunlight on their skin caused irritation. They stared out the windows with awe and unease, as though the world outside the glass were a different planet.

Experts from across Europe converged to help—trauma specialists, child psychologists, social workers. The family was moved to a safe, protected location where they could slowly begin to rebuild their lives. Elisabeth reunited with the three children who had grown up aboveground. It wasn’t easy. Their experiences, their habits, their fears—they didn’t match. One group had known parks and bicycles and schoolbooks. The other had learned to whisper, to move in silence, to fear the creak of footsteps overhead.

But they were together.

And for Elisabeth, that was the beginning of everything.

The trial of Josef Fritzl in 2009 became a media circus. The courtroom brimmed with reporters; the world watched as the man who built a hidden world beneath his house walked in wearing a gray suit, looking almost ordinary. The charges were extensive. The evidence overwhelming. Elisabeth did not have to face him directly; her testimony was recorded. Josef was sentenced to life in prison.

The house was sealed, then emptied, then avoided. No one wanted to buy it. Eventually, the basement was filled with concrete. The bunker was erased from the property, though never from memory.

Elisabeth and her children were given new identities and relocated. Their new home had real windows. Doors that opened. Air that moved. Mountains visible in the distance—vast and blue and unconfined.

They chose privacy. They avoided interviews. A therapist later mentioned that they didn’t want the world to remember them for what had been done to them. They wanted to be remembered for surviving.

The world moved on, but not entirely. Every few years, documentaries resurfaced. American audiences remained fascinated, trying to understand how such darkness could live undetected in a place so seemingly ordinary. The story continues to haunt conversations about hidden abuse, about the complexity of human evil, about the resilience of those who endure the unimaginable.

But for Elisabeth, the story is not about a monster. It is not about a bunker or a house or a headline. It is about freedom reclaimed, children protected, and life rediscovered one sunrise at a time.

And if her story reached the United States—and the rest of the world—it was not because people are drawn to tragedy. It was because humanity is drawn to survival. Because somewhere between darkness and light, her courage became impossible to ignore.

She was never supposed to return.

But she did.

And the world finally saw her.