The red light above the studio camera blinked on, casting a tiny, ominous glow across the polished desk. Somewhere high above Manhattan, in a glass box studio with the skyline of the United States spread out like a poster behind him, Phil Holloway leaned toward the microphone and did what he’d been doing for decades he walked straight into the darkest corners of the American justice system and turned on the lights.

“Welcome to MK True Crime,” he said, his Georgia drawl softened by years in courtrooms. “I’m Phil Holloway. I’m a criminal lawyer, a former cop, and a former prosecutor. I’ve spent almost forty years in and around the justice system in this country. And today, we’ve got a full docket.”

On the monitors in front of him, headlines rolled past New York, Miami, Idaho, Texas, Wisconsin an unruly map of American crime and consequence. The producers in the control room watched the feeds, fingers hovering over switches, ready to cut from one case to the next. Somewhere in a federal prison in Florida, a woman once photographed on yachts and private jets sat in a cell and prepared a last-ditch legal gambit. In Idaho, a convicted killer sat with tens of thousands of donated dollars on his inmate account while the families of four murdered students fought for the cost of their urns. In Miami, a grieving family waited for answers about a teenager who had gone on a cruise and never come home. And in a small apartment in Milwaukee, a shaken community tried to understand how a night of marijuana and paranoia ended with a young pharmacy student dead on a living room floor.

Phil took a breath and set the table the way only a veteran of American courtrooms could.

“Here’s what’s on deck today,” he said. “Ghislaine Maxwell is trying to crack open her twenty-year prison sentence with a new habeas corpus petition, even as reports suggest her life behind bars might be far from miserable. A federal judge has just ordered convicted murderer Brian Kohberger to actually pay restitution, despite his lawyers’ attempts to shield his donated funds. A mysterious death on a Carnival cruise ship off the U.S. coast is starting to look very dark. And later, we’ll talk about wrongful convictions, marijuana paranoia, and why the words we use about predators actually matter.”

He turned slightly toward the cameras, the familiar choreography of live broadcasting flowing through his body.

“And as always, I’m joined by my fellow MK True Crime contributors. From Miami, criminal defense lawyer and former prosecutor Mark Eiglarsh. From California, former homicide prosecutor and author of ‘The Book of Murder,’ Matt Murphy. Gentlemen, let’s start where Congress just pointed fifty spotlights.”

He let the words land.

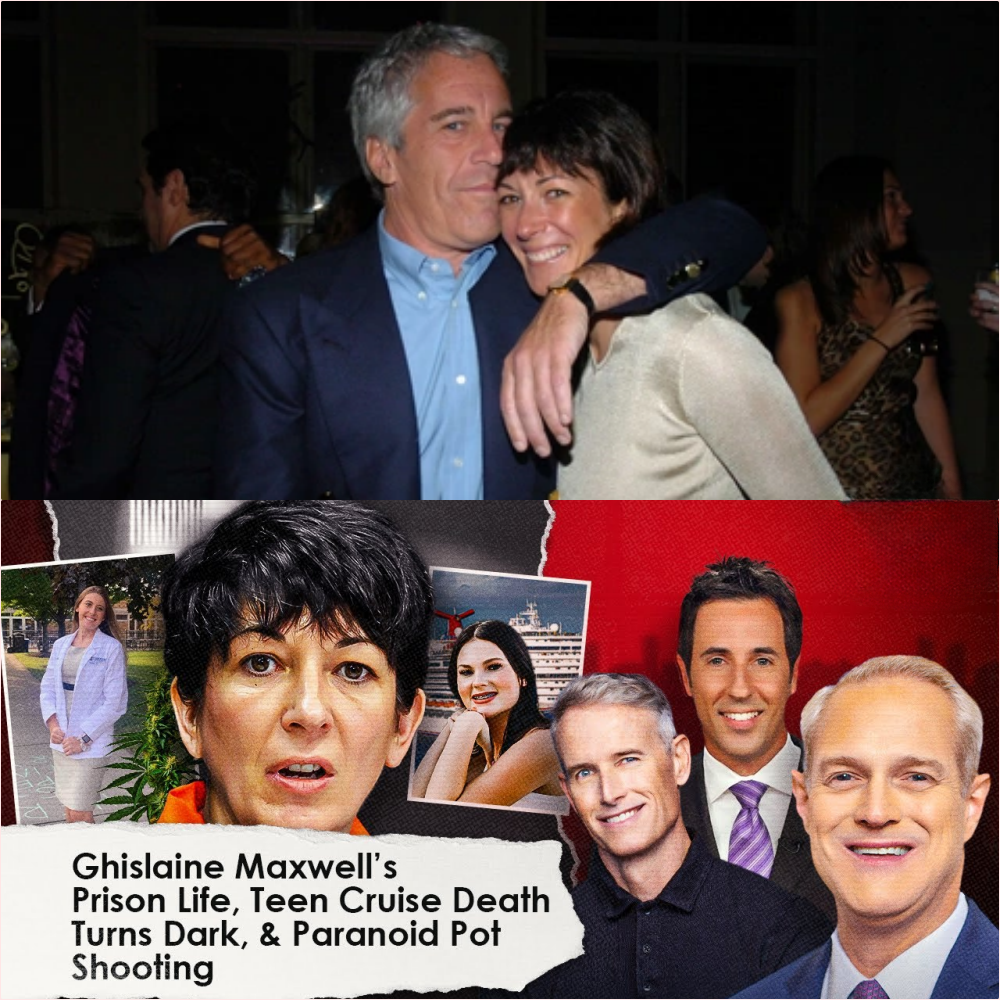

“The House of Representatives has overwhelmingly voted to release the Epstein files. And whenever we say his name, we have to talk about his partner in crime Ghislaine Maxwell.”

The moment he said her name, images flashed in the minds of viewers across the United States. New York townhouses. Palm trees in Florida. Private islands somewhere far out in American waters. Flight logs. Famous faces. And a single woman now dressed in a khaki prison uniform, thousands of miles away from the champagne world where it all began.

Phil leaned into the legal heart of it.

“Here’s what she’s doing,” he explained. “Maxwell is planning to file what’s called a habeas corpus petition. It’s Latin, but forget the language. Think of it as a last legal lifeline for people already convicted, already past their first round of appeals. You’re sitting in a federal prison in the United States, like she is now, and you’re saying to a judge, ‘My imprisonment is illegal. Something about my trial was unconstitutional. Take a fresh look.’”

He paused, letting people in Seattle, Dallas, Miami, and small towns in between picture the inside of a federal courtroom wood paneling, flags, a judge high above everyone else.

“It’s not about relitigating every little mistake. It’s big stuff. Rights trampled. Evidence seized unlawfully. Lawyers so ineffective that your Sixth Amendment right to counsel might as well have been shredded. Or, in her case, so-called newly discovered evidence that supposedly would have changed the jury’s mind. That’s it in plain English.”

He turned toward the split-screen where Mark appeared from Miami, palm trees blurred behind him.

“Mark, you first. Does Ghislaine Maxwell have any real shot with this?”

Mark smiled, the practiced half-grin of a man who had told uncomfortable truths to judges in Florida courtrooms for years.

“Absolutely not,” he said. “Phil, when I hear ‘Maxwell’ and ‘habeas,’ I think of that scene from ‘Dumb and Dumber.’ She’s basically saying, ‘So you’re telling me there’s a chance?’ Habeas petitions are like that. Technically there’s a chance. Realistically? It’s microscopic.”

He lifted a hand as if weighing invisible numbers.

“Roughly twelve thousand habeas petitions get filed in the U.S. every year. About ten percent get any kind of favorable result, and that’s mostly in capital cases all those death row situations. For non-capital cases like Maxwell’s? You’re looking at maybe one percent. One in a hundred. And that’s before you factor in how thoroughly her case was already litigated.”

Phil nodded slowly. Somewhere in New York, the Southern District U.S. Attorney’s office probably felt a phantom pat on the back.

“Matt,” he said, turning to the man on the other side of the country. “You’ve been in those trenches too. Does she have anything here?”

Matt sat in his California office, the Pacific light a faint blur behind him. He had that calm, almost clinical look of someone who had spent years picking apart murder cases in Orange County courtrooms and knew exactly how much weight words carried.

“Mark’s right,” he said. “This case was litigated to the bone. Federal judge in New York knew exactly what it was. The Second Circuit knew. The Supreme Court has already said no once. Her involvement with Epstein? She wasn’t on the edge. She was right in the center. To use a phrase my homicide colleagues favored, she was in it up to her eyebrows.”

He let that sit there, not needing to paint graphic details. The public already knew enough.

“And the impact on the victims was catastrophic,” he added, voice flattening out with the weight of it. “This wasn’t some technical financial fraud. Lives were derailed. Some never recovered. One survivor, the woman who was in that famous photograph with Prince Andrew, later died by suicide in Australia. Real people. Real damage. The Southern District of New York finally did what Florida authorities botched years earlier. I’ve got no doubt they did this case right.”

Phil tapped his pen against the desk lightly.

“One of the claims,” he said, “is that there’s new evidence. Her lawyers say something’s come out since her 2021 trial that would have affected the verdict. Mark, put on your defense hat. How do you convince a court that this new evidence is so strong a jury would have changed its mind?”

Mark shrugged.

“In the abstract? You can’t. First question is, what’s the evidence? If I’ve got something showing she was framed from day one, that’s different. But look, I have to say this as a defense lawyer who believes deeply in due process: if there is something real, something that shows she didn’t get a fair trial, I want that fixed, no matter how little sympathy I have for her personally. The system has to be fair even for people we can’t stand. It’s just that in this case, I haven’t seen anything even close to that threshold.”

Phil nodded, then shifted from the courtroom to the broader public reckoning.

“The victims are making sure we don’t forget,” he said. “Right now there’s a PSA floating around survivors of Epstein and Maxwell looking into the camera, holding old photos of themselves as teenagers. ‘This was me when I met Jeffrey Epstein.’ ‘I was fourteen.’ ‘I was sixteen.’ They say there are about a thousand of them. They’re calling for the secrets to finally come out of the shadows.”

Across the United States, people watching from their living rooms and offices could almost see the images as he described them faded snapshots of American girls, all braces and big hair and hope, long before private jets and closed doors.

“And at the same time,” Phil continued, “we’ve got a new controversy brewing inside a federal prison in Texas.”

He glanced down at his notes, but he didn’t really need them.

“A federal prison nurse in Brazoria County, Texas, named Noella Turnage has come forward calling herself a whistleblower. She says Maxwell is getting special treatment Warden personally handling her mail, extra privileges, the whole nine yards. And that alone would be a story. But here’s the part that should make every American nervous.”

He let the tempo drop.

“This nurse also admits she got access to attorney–client communications between Maxwell and her lawyer. Emails. And she forwarded them to Congress as part of her whistleblower package.”

He turned back to Matt.

“Matt, you called attorney–client privilege ‘sacred’ earlier. How big a problem is this?”

Matt’s expression hardened.

“It’s huge,” he said. “In American law, a few things are almost untouchable. Your communications with your lawyer. With your doctor. With your therapist. With your clergy. These are relationships that our justice system has carved out and protected because without them, the system collapses. If inmates in federal prisons think staff can read and forward their private legal communications to Congress, to anyone, good luck ever getting an honest word out of any defendant again. It won’t just hurt Maxwell. It will hurt every person who ever needs a lawyer.”

He leaned a little closer to his camera.

“If Maxwell is getting unfair privileges? Blow the whistle all day long. That needs to be exposed. But attorney–client emails? That should never see daylight. Congress should seal that material immediately and make it clear that line was crossed.”

Mark nodded vigorously from Miami.

“It’s a balancing act,” he added. “We absolutely want whistleblowers to come forward when someone in a U.S. prison is getting special treatment they don’t deserve. She shouldn’t be getting extra biscuits, extra phone time, or a private concierge warden. But the moment you open an envelope or an email clearly marked attorney–client? You’ve stepped on a landmine. That undermines confidence in the system itself.”

Phil exhaled slowly.

“And there’s one more wrinkle,” he said. “Last summer, the Deputy Attorney General the number two official in the Department of Justice took a trip down to Maxwell’s prison and met with her personally. They sat down for a long conversation. We don’t know what was said. But when a high-ranking DOJ official spends that much face-time with a convicted co-conspirator in a case like this, you have to consider the possibility she’s a cooperating witness. And if she is, some of that ‘special treatment’ might be tied to that cooperation. We just don’t know.”

He let that hang in the air a beat, then pivoted.

“And that’s not the only story right now about justice, money, and expectations inside the U.S. legal system. Let’s talk about Idaho.”

The screen behind him shifted to snowy mountains and a brick house in Moscow, Idaho, the site that had haunted American television screens not that long ago.

“Brian Kohberger,” Phil said quietly. “He’s the man who pleaded guilty to the November 2022 murders of four University of Idaho students Kaylee Goncalves, Madison Mogen, Xana Kernodle, and Ethan Chapin. This case seized the whole country. Influencers, YouTubers, people across the U.S. were glued to every piece of discovery, every breadcrumb. We were going to launch this very show around his trial, before he abruptly pleaded guilty.”

He picked up a sheet of paper and tapped the top line.

“As part of that plea, he agreed to pay restitution to the victims’ families. That included paying for the urns that hold their remains. Not a fortune. Just a few thousand dollars. But here’s the twist. Before his plea, while he sat in jail, he became the focus of a strange little movement. People who believed he was innocent started sending him money. By the time sentencing rolled around, he had more than twenty-eight thousand dollars on his inmate books.”

Phil shook his head slightly.

“And his lawyers still tried to argue that he shouldn’t have to pay the restitution.”

He turned back to Matt.

“Matt, was it appropriate for his defense team to fight that obligation after he’d already agreed to it in a U.S. courtroom?”

Matt’s jaw tightened.

“They’ve got a job,” he said. “Defense lawyers in America are obligated to represent their client’s interests vigorously. That’s the oath. But there’s also basic decency. When you’ve murdered four young people in their college home, and their families are just asking you to pay for the first urns they ever hoped they’d buy one for their child’s ashes instead of a bridal bouquet or graduation cap that’s the last fight you should be picking.”

He shook his head.

“The judge in Idaho did exactly the right thing. He looked at the plea agreement, he looked at the donations, and he said, ‘No. You’re paying this.’ The law allows it. The morality demands it.”

Mark jumped in.

“This is where the tension is real,” he said. “As defense counsel, sometimes you’re asked to make arguments you personally find offensive. I had a client just this week who wanted me to argue something that I knew would deeply hurt the victim’s family and backfire. I literally begged him to let it go. If he hadn’t, I would have had to decide if I could still represent him. The client doesn’t get to completely control the lawyer like a puppet. We have judgment, too.”

Phil’s eyes narrowed thoughtfully.

“The judge in Idaho pointed out that Kohberger is young,” he added. “He’ll likely have decades in a U.S. prison system where he can work inmate jobs. Maybe he’ll get media offers, book deals, or other attempts to profit from his infamy. And if he ever does, every dollar should have the victims’ families at the front of the line. That’s what victim restitution laws in this country are for.”

He let that thought settle and then shifted gears again.

“Speaking of media,” he said, “Lifetime yes, the Lifetime network is planning a ‘ripped from the headlines’ movie about the Idaho case. The families are pleading with them to stop. There’s even a petition now, growing by the day. Mark, is this too soon?”

Mark sighed.

“For my taste, absolutely,” he said. “Emotionally, it feels distasteful. But legally? Under the First Amendment in the United States, Lifetime has broad protection. They can make dramatizations of true crime, and they do it all the time. The families are doing the only thing they can: appeal to public conscience. Tell viewers, advertisers, anyone who will listen, ‘This hurts us. Don’t reward it.’ And maybe, if enough people refuse to watch or buy products during those ad breaks, the economic reality will speak louder than the legal one.”

Phil didn’t argue. He’d seen too many courtroom dramas that never showed what it felt like for the parents sitting in the second row, watching actors play the worst day of their lives.

“Now,” he said, “let’s leave Idaho and travel south. Way south. To open water.”

The screen behind him shifted again, this time to a gleaming white Carnival cruise ship cutting through blue ocean, its decks stacked with bright railings and tiny human silhouettes.

“Anna K. was an eighteen-year-old cheerleader,” Phil said, his voice softening. “She lived in the United States. She had plans to join the military after she graduated high school this year. She boarded a Carnival cruise ship in November 2025 with her family, leaving a U.S. port, expecting sun, buffets, and selfies. Instead, she was found dead on board.”

He let the words sink in, no need for sensational detail.

“Here’s what we know from reporting so far,” he continued. “Her family says that one night on the cruise, she told them at dinner she wasn’t feeling well. She went back to her cabin. The next morning, she didn’t show up for breakfast. The ship still had thousands of passengers on board. The family started searching everywhere from pool decks to game rooms. Hours passed. A cabin attendant finally went to clean one of the rooms and found Anna’s body.”

He paused.

“The ship diverted to PortMiami. The Miami-Dade Medical Examiner’s Office took custody of her remains. And the FBI because this happened in U.S. waters and involved an American citizen took over the investigation.”

He took a breath and then stepped into the storm.

“Then came a tweet. A man claiming to be her uncle posted a detailed allegation on X formerly Twitter saying she’d been found hidden under a bed in a cabin, wrapped in a blanket, covered with life vests. He said she was killed by a stepbrother. He described it with the kind of detail that either comes from someone who knows the case intimately, or someone who’s letting imagination run wild. The tweet went viral. Then it was deleted. But screenshots, of course, live forever.”

Phil turned to Mark.

“Mark, this happened off the Florida coast, within reach of Miami. That tweet is either explosive truth or devastating defamation. Where does the law land?”

Mark’s knuckles tightened just slightly around his pen.

“If it’s false,” he said, “then the person who posted it has painted a huge target on his own back. In the United States, accusing someone of murder publicly is about as defamatory as it gets. The alleged stepbrother could sue. Hard. On the other hand, if the uncle has real information, then law enforcement needs every word, but they need it in an interview room, not on social media. Either way, he should have kept that off the internet.”

Matt chimed in.

“There’s another problem,” he said. “If he becomes an important witness, that tweet becomes a sword against him. Defense lawyers live to attack credibility. Any inconsistency between what he wrote online and what he says under oath will get magnified in a U.S. courtroom. Prosecutors in Miami and FBI agents probably paid him a visit, politely or otherwise, after that tweet. I wouldn’t be surprised if the deletion came after a conversation at his front door.”

Phil nodded.

“And while the public demands answers,” he added, “the FBI stays mostly silent. The medical examiner knows how she died. They’ve done the post-mortem. In a U.S. autopsy, they determine cause and manner of death homicide, accident, suicide, or undetermined. Right now, they’re not sharing. That vacuum gets filled with rumors, threads, and YouTube theories.”

Matt lifted a hand.

“Sometimes silence isn’t about hiding,” he said. “If there’s a juvenile suspect, different rules apply. If there’s a fragile case forming, you can’t dump details into the American media and expect to find twelve impartial jurors later. As frustrating as it is, the most responsible thing the FBI can do right now might be to keep their mouths shut while they work.”

Phil exhaled, then turned the spotlight to a very different kind of tragedy in the American Midwest.

“Let’s go to Wisconsin,” he said. “To a quiet house, too much marijuana, and a night that ended with one friend dead and another charged with homicide.”

He gave the bare bones.

“In Milwaukee, prosecutors say a thirty-one-year-old woman named Jamaica Mills was at home on November 4th with a Concordia University pharmacy student. The two of them smoked marijuana together strong, modern strains, not the mellow stuff your grandparents might remember. According to the criminal complaint, both became extremely paranoid. At some point, instead of simply giving this young man a haircut with scissors like he’d come to do, Mills retrieved a handgun. Before the night was over, he was dead from a gunshot wound, and she had shot herself as well.”

He shook his head.

“We’ve all heard it: ‘It’s just weed. It’s harmless.’ But in courtrooms across the United States, lawyers are starting to see a different story. Stronger strains. Edibles that hit like a freight train. Vulnerable minds.”

He looked at Matt.

“Matt, you saw something like this in California, didn’t you?”

Matt nodded slowly.

“Very similar,” he said. “A young woman with no criminal history, Netflix-and-chill night with her boyfriend, strong marijuana, maybe laced, maybe just potent. She had what could only be described as a psychotic break. She killed him. No background, no pattern, just one terrible night. In that case, the marijuana wasn’t a full legal defense, but it absolutely mattered. It went to her mental state, to whether she could form the intent required for murder. The law in the United States draws a hard line against ‘I got high, so I’m not responsible.’ Voluntary intoxication isn’t a get-out-of-jail card. But when the drugs push someone into genuine temporary insanity, judges and juries sometimes treat it as mitigation.”

Mark nodded.

“This is where criminal law in America becomes a court of equity,” he said. “It’s not just black letters on white pages. It’s fairness. Prosecutors ask: is this a cold-blooded killer, or someone who made a catastrophic decision in an altered state they’ll never repeat? Defense lawyers argue: this was a one-off meltdown, not a pattern. The judge tries to land somewhere that protects the public but acknowledges the complexity. There’s nothing simple about these cases.”

Phil glanced toward the studio clock. Time was moving. There were still more stories to tell.

“We’ll be watching that Wisconsin case,” he said. “But before we get to closing arguments, we have to talk about something a little lighter, but still very much tied to the world we’ve been walking through today the MK Live Tour.”

He smiled.

“Megan Kelly’s been taking this show on the road,” he explained. “From Miami to Atlanta, from Bakersfield to Anaheim to Glendale, Arizona. Theater after theater across the United States filled with people who want to talk about crime, courts, and media face-to-face, not just through screens.”

He glanced toward Mark.

“Mark, you were on stage with her in Miami. How was it?”

Mark’s face lit up.

“The energy was electric,” he said. “South Florida crowd in a packed theater, live Q&A where people lined up at microphones and Megan had no idea what they were going to ask. No scripts. No handlers screening questions. She answered every one. Funny, serious, emotional. You don’t always get that kind of authenticity in television. It was fun, and it reminded me why we do this because people out there actually care about how the system works.”

Phil nodded.

“I was on stage with her in Atlanta,” he added. “We were in the backyard of the Fulton County Courthouse, essentially. The crowd there was very, very happy to see one particular person our friend Ashley Merchant, who’s been all over the news for her work in those Georgia cases. And Mark’s right. The moment when Megan takes raw questions from the audience is worth the ticket by itself. People stand up and ask everything from politics to prosecution and she takes it all head-on.”

He turned toward Matt.

“Matt, you’re about to join her at the Honda Center in Anaheim with Mark Geragos, right?”

Matt nodded.

“Yes,” he said. “We’ll be out there on the West Coast. I can tell you this: every one of the tickets they gave me is going to a cop or a family member of a cop. Law enforcement loves talking to someone who understands victims and isn’t afraid to push against bad narratives about them.”

Phil smiled.

“And that’s a nice segue into our mailbag,” he said. “Because people don’t just want to hear about cases. They want to know how guys like us ended up here in the first place.”

He picked up a printed email.

“Mary Jane writes, ‘Love the show. I listen every Wednesday and Friday. I’m interested in the career trajectories of the lawyers. Did you always want to go into law and did you have other careers before?’”

He looked up.

“Matt, you start.”

Matt took a slow breath, memories flickering across his face.

“I didn’t grow up dreaming of filing motions,” he said. “Like a lot of lawyers, math wasn’t exactly my friend. But in college, someone very close to me was sexually assaulted. I walked that road with her police reports, hospital visits, interviews, all of it. It changed me. I decided I wanted to be the person on the other side of that table, the one making sure predators didn’t get to walk away.”

He settled into the story.

“I went straight from undergrad into law school. Because of some sexual assault work I’d already done, the FBI recruited me. My ego loved that, I won’t lie. But the Orange County District Attorney’s Office recruited me too. A woman from their sex crimes unit, Kathy Harper, brought me in. In California, everybody starts in misdemeanors. Then I spent three and a half years in sex crimes eighty-plus percent cases involving child victims, the rest adults. After that, I moved into homicide. Those two worlds overlap a lot more than people think. I’ve spent much of my life staring monsters in the face in Southern California courtrooms and saying, ‘Not today.’”

He paused.

“Now, in private practice, I still represent victims pro bono under California’s Marsy’s Law. I stand with them in court, not as their criminal lawyer they have prosecutors but as their advocate. I’ve got the therapy bills to prove those years left a mark, but I’d do it all over again.”

Phil turned to Mark.

“Mark, your path was different,” he said.

Mark laughed softly.

“Very,” he said. “I didn’t want to be a lawyer. Not at all. I majored in radio and television production. I wanted to be doing exactly this explaining big issues in entertaining ways. My father, though, had other ideas. Or so I thought.”

He smiled at the memory.

“I heard him say, ‘You have to be a lawyer.’ So I went to law school. Ten years into my practice ten years of courtrooms in Florida, defending people, sometimes prosecuting I confronted him. I said, ‘Dad, I’m mad at you. I wanted to be on TV and you made me a lawyer.’ He looked at me and said, ‘No. I said get your law degree first. It will help you with whatever you decide to do. You chose to be a lawyer. And by the way, I paid for law school. You’re welcome.’ Then he said, ‘If you want to go be on TV, go make it happen.’”

He spread his hands.

“So I did. Now I get to practice law and talk about it on shows like this. Best of both worlds. And I owe that to my father’s mix of stubbornness and wisdom.”

Phil took his turn.

“I wanted to be in the sky,” he said. “When I was sixteen growing up in the United States, I worked after school at a department store in a mall. Every paycheck burned a hole in my pocket. So I took flying lessons. I wanted to be an airline pilot. I still love airplanes. But somewhere along the way, law enforcement started calling louder. I joined a police department. I worked nights. Every time I made an arrest and the suspect didn’t bond out, I had to be in court the next morning for a preliminary hearing. I sat there in the back of the courtroom watching prosecutors do their thing, and I thought, ‘I could do that better. I could ask better questions. I could be more prepared.’”

He smiled.

“So I went to law school. The U.S. military grabbed me and said, ‘We know you want to prosecute, but first you’re going to defend.’ They made me a defense lawyer in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps and shipped me to the West Coast. Later I came back to Georgia and joined a district attorney’s office in the Atlanta area. Then private practice. And now here, with you all, using everything I’ve seen to help people understand how this system really works.”

He put the paper down.

“And that brings us to our closing arguments. The part of the show where we step back from today’s cases and talk about the bigger picture.”

He turned to Mark.

“Mark, you get first crack.”

Mark nodded, his expression growing serious.

“People often ask me,” he said, “‘How do you defend guilty people?’ It’s a fair question. The answer is complicated. But part of it is simple: they’re not always guilty.”

He glanced off-screen for a moment, as if replaying a scene in his mind.

“Years ago, in Homestead, Florida, south of Miami, there was a handyman named Miguel. He was arrested for a brutal crime charged with kidnapping, beating, and sexually assaulting a teenage girl he supposedly grabbed from a party. The victim went on Facebook, looked up the guy whose party it was, searched his friends for someone named Miguel, and pointed: ‘That’s him.’ Based on that, police slapped handcuffs on my client and called it a day.”

He shook his head.

“By the time his parents came to see me, Miguel had been sitting in a Miami-Dade jail for thirty days. Non-bondable offense. Facing a life sentence. He thought his life in the United States was over. To be honest, at first I didn’t want the case. It sounded ugly. But his parents were desperate. They said, ‘Look at his tattoos. The victim never mentioned tattoos. And look at these text messages. It doesn’t even seem like he was at the party at the time she says this happened.’”

He lowered his voice.

“I went to the prosecutor. I said, ‘I think you might have an innocent man.’ She brushed me off. Told me she didn’t work past five p.m., told me to email her later. That did not go over well with me. I said some words I’m not proud of words normally reserved for when you stub your toe at three in the morning. Eventually, I went over her head. Her supervisor told me they had taken DNA and that we’d just have to wait six months for lab results. I said, ‘No way. I’m not letting an innocent man sit in jail for half a year while we wait for a swab.’ I begged. She finally agreed to rush the test as long as I promised not to tell my colleagues she did.”

He smiled faintly.

“The DNA came back. It wasn’t Miguel. In fact, it pointed to another man entirely a different Miguel, who was eventually arrested and convicted. There’s a photo somewhere in the Miami Herald archive, showing me and my client walking out of Judge Block’s courtroom after his release. An innocent man, nearly buried by a bad ID and a rushed system.”

He looked straight into the camera.

“So when people ask me how I can defend people accused of terrible things, that’s part of my answer. Because sometimes, in the United States of America, the person sitting at the defense table really didn’t do it. And if lawyers like me don’t fight for them, no one will.”

Phil nodded slowly.

“Matt,” he said. “You’re up.”

Matt leaned forward.

“I want to talk about good guys and bad guys,” he said. “And I want to talk about words.”

He took a breath.

“The Epstein files are back in the U.S. news this week. Along with that, some people have been attacking Megan Kelly because she made a precise point about language: Jeffrey Epstein wasn’t technically a pedophile. He was something else, just as monstrous. And a lot of folks heard that and thought she was defending him. She wasn’t. She was doing what people who actually work with these cases do every day using the right term.”

He held up three fingers.

“When you rotate into a sex crimes unit in a U.S. prosecutor’s office, day one, they teach you this. There are three main categories of offenders. People who target pre-pubescent children those are pedophiles. People who target early pubescent kids, teenagers we call those hebephiles. And people who target older teens, sometimes just past the line of legal consent we call those ephebophiles. These are clinical terms, used in the DSM-5 and in training for detectives, prosecutors, and therapists.”

He leaned back, eyes hard.

“When Megan said Epstein was not technically a pedophile, she wasn’t soft-pedaling his evil. She was using the precise term professionals use. Anyone who’s actually worked in sex crimes in the United States knows this. But some of the people attacking her especially those from the ‘defund the police’ crowd do know better. They’re weaponizing survivors’ understandable anger over terminology to attack someone they already don’t like. And here’s the ugly twist: defunding police in America almost always means cutting specialized units first. You know what the first specialized unit to go often is? The sex crimes unit. The one investigating predators like Epstein before they can hurt again.”

He shook his head slowly.

“Serial killers are rare. The FBI estimates maybe a few dozen active at any time in the United States. Sexual predators are everywhere. When you strip detectives from those units, predators win. When you discourage precise language and call any attempt at nuance ‘defending monsters,’ predators win. Megan Kelly spent more than ten years as a lawyer. She knows words matter. She got this exactly right. And I’ll say this plainly: she’s one of the good guys. Cops know it. Survivors know it. She gives victims a real voice. And if anyone wants to debate that on any platform in this country, I’m here for it.”

Phil nodded once.

“Time for my closing,” he said quietly. “And I want to talk about something that doesn’t get enough airtime wrongful convictions in the United States.”

He let a beat pass.

“Our system is one of the best in the world. I believe that. But it’s not perfect. Across this country Georgia, California, New York, Texas, everywhere there are people sitting in cells right now who did not commit the crimes on their paperwork. We know that, not just from gut feeling, but from numbers. Since 1989, more than 3,600 people have been exonerated in the U.S. after being wrongfully convicted. Another few hundred before that. In recent years, we’re talking about roughly 150 exonerations per year. Those are just the ones we’ve found.”

He leaned into the camera.

“How does it happen? A lot of ways. Mistaken eyewitness identification is a big one. You’re standing on a U.S. street corner at night. It’s raining. You’re stressed. A man with a gun runs past. You get one look at his face under bad lighting. Six months later, you’re in a lineup room at a police station. The officer says, ‘Take your time.’ You don’t want to let anyone down. Your brain fills in gaps. You point to someone. ‘That’s him.’ And if the system doesn’t check that carefully if no one asks the right questions an innocent person can end up in a jumpsuit because human memory is a lot more fragile than television makes it look.”

He continued, voice steady.

“Forensic evidence is another double-edged sword. Done right, DNA in the United States is an extraordinary tool. It’s cleared hundreds of innocent people. But we’ve also seen other so-called ‘science’ crumble like bite mark analysis. For years, juries were told that teeth indentations were as unique as fingerprints. Experts took the stand and pointed to dental molds. People went to prison. Some went to death row. Then better research came, and we realized bite marks are wildly unreliable. Those old convictions didn’t just vanish. Real human beings had to fight, for decades in some cases, to get someone to admit the science had been wrong.”

He took another breath.

“False confessions? They’re real. I’ve seen them. Long interrogations in U.S. police stations. Threats. Promises. Sleep deprivation. Vulnerable suspects kids, people with mental health issues finally say, ‘Fine, I did it, can I go home now?’ Not realizing that once those words are on tape, they may never go home again. Studies of DNA exonerations show that in over a quarter of those cases, the convicted person had confessed. That’s a terrifying number.”

He let a bitter note creep in.

“Then there are the jailhouse informants. The snitches. The person in the next bunk in a county jail in the United States who suddenly claims, ‘He told me everything. He confessed to the whole crime. And by the way, I’ll gladly testify if you can shave some time off my sentence.’ Sometimes they’re telling the truth. Sometimes they’re spinning fairy tales. If prosecutors and judges don’t scrutinize those stories ruthlessly, we get wrongful convictions built on lies told for cigarettes and commissary credit.”

He paused, then went to the one part of the system closest to his heart.

“And we can’t ignore the professionals. Police officers who cut corners. Prosecutors who withhold exculpatory evidence what we call Brady material because they’re tunnel-visioned on a conviction. Defense lawyers who are overworked, under-funded, or just plain careless. Inadequate counsel is a real, legally recognized basis for overturning a conviction in the United States because we recognize that if you go into a courtroom without a competent fighter in your corner, the match is rigged before the bell even rings.”

He sat back, the studio lights reflecting faintly in his eyes.

“Organizations like the Innocence Project and local conviction integrity units across this country have helped free hundreds of people. They dig out old case files from courthouses in places like Dallas, Chicago, New Orleans, Atlanta. They re-test evidence, re-interview witnesses, expose junk science. But every time we celebrate an exoneree walking out of a U.S. prison gate after twenty or thirty years, we should feel something else too: a cold dread. Because for every wrongful conviction we uncover, there are likely more we haven’t found yet.”

He let the silence speak for a moment.

“The system is human,” he said at last. “Which means it’s flawed. But it also means it can change. We can tighten lineup rules. Improve forensic standards. Record every interrogation in every precinct in America. Train prosecutors to value justice over conviction stats. Fund public defenders properly so they can actually investigate, not just process pleas. That’s what we try to do on this show to hold a mirror up to the U.S. justice system, not because we hate it, but because we want it to live up to its promise.”

He gave the camera a final, steady look.

“Thank you for being with us today,” he said. “From New York to Miami, from Idaho to Wisconsin, from cruise ships off the U.S. coast to small-town courtrooms, these are our stories. They’re messy, imperfect, and deeply human. If you’ve got case suggestions, questions, or comments, send them our way. Until next time, I’m Phil Holloway. This is MK True Crime. Take care of yourselves and pay attention. Because in the United States, what happens in our courts happens to all of us.”

The red light over the camera went dark. The studio dimmed. But in homes and cars and earbuds across America, the echoes of everything he’d just laid out kept moving through minds, through conversations, through the fragile machinery of justice itself.