The sound of silk tearing under a chandelier can cut through a ballroom louder than any orchestra. One heartbeat I was smiling at a stranger’s comment I didn’t hear; the next, the zipper at my spine slid and my dress sloughed forward like a curtain yanked from its rail. Two hundred screens glared up like cold moons, little white rectangles lifted as one. Under the glassy rain of camera clicks and diamond light, the woman I had tried so hard to be—patient, grateful, invisible—broke in half.

They called me a gold digger before anyone thought to call security. Someone’s flute of champagne chimed against a cufflink. The violinist laid his bow flat and pretended to tune. A whisper rippled across the marble like a draft under a door: there she is, look at her, look. Clarissa Whitmore, my mother-in-law, smiled the way a blade gleams, and when she said the word thief it rang off the crystal chandeliers draped over the main hall of the Whitmore estate in Greenwich, Connecticut. Her daughter Natalie—silver gown, silver tongue—stood shoulder to shoulder with her like the second hand on a watch, always a half-beat late, always moving in the same circle. “You were in my dressing room,” Clarissa said, and I could feel 200 sets of pupils pin to me, like dressmaker’s pins pressed into a mannequin that does not bleed.

My name is Mia. I am supposed to tell you to stay until the end because the ending will leave you speechless; that’s what the thumbnails say below every viral clip. It’s not a cliff I’m selling you; it’s the climb. Because what happened in Greenwich that night—what Clarissa and Natalie did, what Adrian didn’t do, what my father did after—wasn’t a twist so much as gravity doing its job after years of being ignored. If you’ve ever stood in a room in the United States where money makes the rules and you are not the rule maker, you already know the scent: cut flowers and polished wood and the faint electronics of phones ready to film your humiliation.

We had come to celebrate our second anniversary. Correction: Clarissa had summoned, curated, and sponsored it as if love were a museum exhibition and she the sole docent. The Whitmore estate unrolled itself from the drive like a magazine spread: a red carpet over Connecticut stone, a canopy of imported roses, a live orchestra in black at the end of a pool lit from below. Inside, waiters navigated the ballroom with trays that sparkled like applause; tables bore place cards inked in a hand prettier than mine would ever be. It wasn’t a party so much as a statement in cursive: this family rules the East Coast society pages, this family dines on the same street as Park Avenue legends, this family gives to hospitals with their name on the wing. It wasn’t for us. Parties at that altitude rarely are for love—they are for the altitude.

I had chosen a cream dress on sale and pinned my hair with a barrette from a drugstore because I naively believed sincerity reads under any light. Adrian kissed my forehead at the door and was immediately absorbed by his father’s orbit of men who wore their watches like they wore their last names: heavy, gleaming, inherited. Vincent Whitmore nodded at me once the way a doorman nods at a package. Then he forgot I existed.

For months, Clarissa had made a hobby of sanding me down to the smallest version of myself. “The girl Adrian married,” she would say, never the name, to donors and wives and women who looked at me and saw a mirror they would never hang in their home. She passed me cups of tea like she was passing me evidence of the crime of my presence. Natalie perfected the sugar knife: your dress is adorable, I saw something just like it on a clearance rack, how lovely that you can make inexpensive things look… serviceable. If I was quiet, I was meek. If I dared a sentence with an opinion, I was gauche. If I didn’t show up, I was ungrateful. If I did, I was opportunistic. Their math always added up to the same answer: I did not belong.

What no one at the Whitmore estate knew that night—not Clarissa with her pink diamond necklace she pretended not to check every twenty minutes; not Vincent, who spoke about the market as if he hand-painted it each morning; not even Adrian, the man I loved and married on purpose in a tiny county courthouse two years earlier—was that my last name wasn’t the one they had been practicing disdain on. I had changed it at eighteen, the same summer I moved out, traded penthouses for an apartment with a door I could lock myself, traded drivers for a used Civic that coughed sympathy on winter mornings. The world I left bore my father’s signature on skyscrapers and trust agreements. He is a self-made American billionaire, which is to say he does not believe in luck except the kind you make other people think you didn’t plan. He taught me to be suspicious of smiles that arrive with invoices. He loved me enough to let me choose a life outside his shadow with one condition: if I ever truly needed him, I would call.

I did not call when Clarissa introduced me to the board as “the young lady who is learning” because apparently a business degree I paid for with a job at a coffee shop did not count. I did not call when Vincent walked through me in the kitchen like I was a draft. I did not call when Natalie put her arm around me in public and then joked in a bathroom about how some boys marry down to feel up. I told myself endurance was nobler than escalation. I told myself Adrian would find his voice between us. I told myself love would be enough because a girl who walked away from a world of private jets at eighteen wants to believe love is the only currency that can’t be forged.

Then the orchestra paused and Clarissa pressed a hand to the base of her throat and said the magic words that turned the party from performance to tribunal: “My necklace. The pink diamond.” You could feel the room lean in. You could feel the phones rise. She pivoted to me as smoothly as a ballerina turns toward a spotlight she commissioned. “Mia was in my dressing room,” she said, and the way she said my name made it sound like a misdemeanor.

“No,” I said, which was both a fact and also a prayer. “I was looking for the bathroom.”

“I saw her,” Natalie added, the echo built into the original sound. “Near Mother’s jewelry case. She looked—confused.” The word degraded as it dropped out of her mouth, as if it did not deserve the weight of the “d.”

“Why would I steal from you?” I asked, and my voice shook because I was not prepared to be cast as a thief in a house that could have paid for ten neighborhoods of rent with the arrangements of flowers alone. “I don’t want your necklace.” I wanted my husband.

“Everyone knows why you’re here,” Clarissa said, and there it was, the unkind nucleus around which everything else had orbited for two years: you are here for our money. “Search her,” Vincent said in the tone men use when they have never had to say please to get what they want. “Publicly. If she’s innocent, she has nothing to hide.”

If you are wondering what kind of security does not pause before they lay hands on a woman at her own anniversary party in the United States of America, I would remind you that money is the most reliable uniform there is. Two men in suits approached me with the soft faces of people who think they are the hands of someone else’s decision. I looked for Adrian and found him without finding him; he was five feet away and thirty miles out to sea. “Please,” I said, in a voice I almost didn’t recognize as mine, and what I meant was help me, say my name and attach it to the word wife, tell the people who texted you congratulations this morning that the person they congratulated is a human being.

He didn’t say anything.

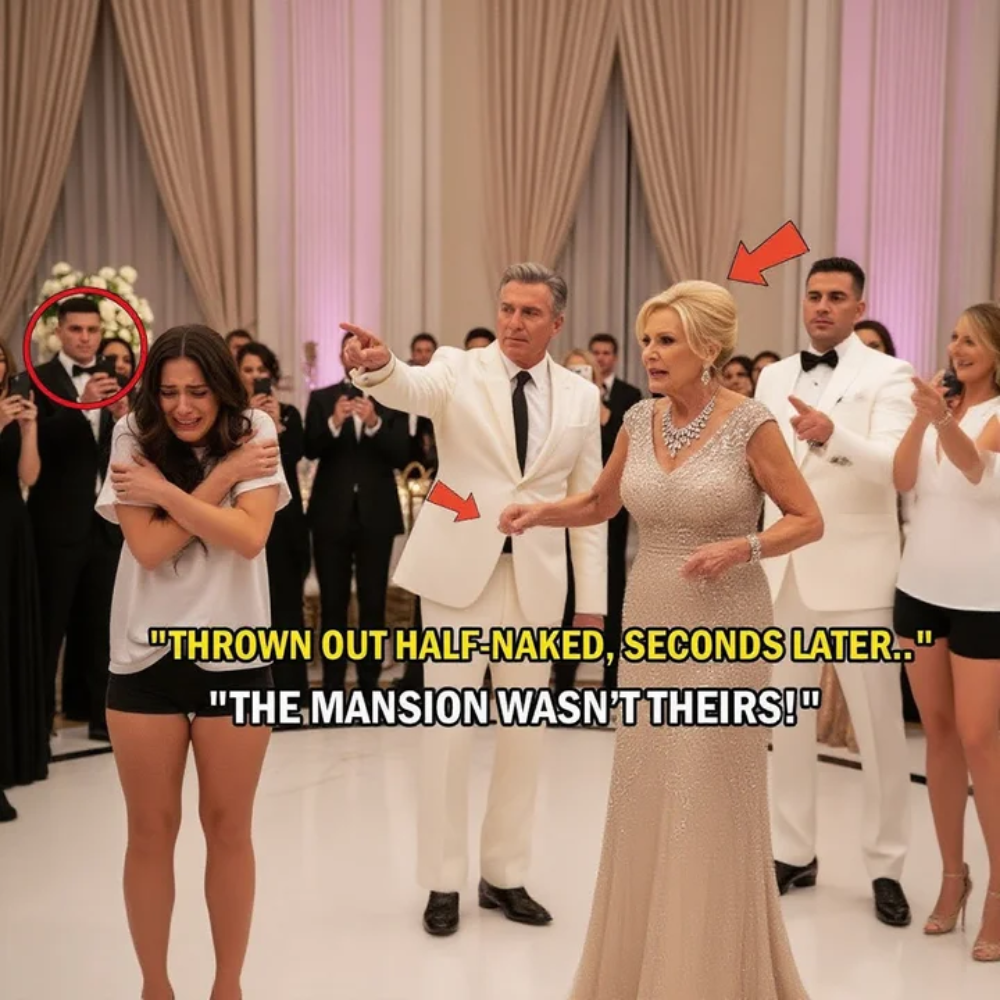

Clarissa did. “Let’s make this easy,” she said, and when their fingers dragged under the seam and the zipper gave, what the cameras filmed was not my body; what they filmed was the precise moment a marriage failed to be a shelter. My dress came away like a lie I had told myself and I stood in the cold center of a room full of heat and donors and heirloom diamonds in undergarments designed to disappear under fabric. If this sentence is hard for you to read, I am telling it right. I wrapped my arms around myself and learned that shame has a temperature; I could feel it radiating from the phones like they were radiators someone had installed just for this.

They shook my dress. They found nothing except their reflection in the sheen of cruelty. They declared that finding nothing did not mean nothing existed. The crowd performed pity exactly as well as a crowd that craves a spectacle always does: averted gazes paired with tilted phones, little gasps fed to the massive mouth of the internet. Clarissa called me a thief in a tone she had probably practiced in front of a mirror. Natalie performed outrage like she performs kindness: expensive, empty. Vincent ordered me removed from property he believed he owned with the confidence of a man who has never had a mortgage payment denied. Security took my arms. I looked at Adrian and in the space where a husband should live I saw absence and ambition and a small, blond boy who never learned how to say no to his mother. He turned away before the doors swallowed me.

There is a moment cold hits you so cleanly you stop shaking. The front steps of the Whitmore estate were made for magazine covers; at midnight they are good for learning whether you are a person who can survive being thrown out of the life you have been pretending is yours. The night air nudged goosebumps into my skin. I sat on stone and tried to breathe through the kaleidoscope panic gives you when you’re wearing almost nothing and you cannot find your purse and you can hear music start again in the house that just ejected you. A young valet—twenty at most, eyes kind in the way eyes are kind when they’ve been taught to look up at faces and mean it—took off his jacket and held it out like the first smart thing anyone had done all evening. I put it around my shoulders and felt its heat as if it had been knit by my grandmother. I asked to borrow his phone.

There are numbers that live in your fingers even when the rest of you cannot find your name. Mine belonged to the man who raised me to count myself first, to add up the cost, to subtract the noise, and to multiply what mattered. He answered on the second ring because fathers who were poor before they made their first million never stop answering phones as if every call might be a fire starting. “Dad,” I said, and it came out like I had swallowed glass. “I need you.”

“Where,” he said. Just that. He already knew the rest.

“Greenwich,” I said. “The Whitmore estate.”

I told him the rest anyway. I told him about the necklace, the accusation, the circle of people who chose to film rather than raise a hand. I told him about the dress, the rip, the way my name sounded in Clarissa’s mouth like something she would rinse out. I told him about Adrian watching and not seeing, about the guards and the black gate closing, about the taste of metal fear leaves at the back of your tongue. On the other end of the line a door opened, footsteps moved, something like the metallic slide of a key case, the silky brief click of strategy finding its shoes. “Do not move,” he said. “I’m coming to get you. And Mia?” He paused, and in the pause the man who once sold tires out of a borrowed van breathed in a way that told me a different kind of vehicle was about to roll. “They have no idea what’s about to hit them.”

Fifteen minutes later the night blinked and became day. A wash of white light fell out of the sky like a verdict and the beat of rotor blades sponged the sound out of the leaves. Ten black SUVs slid to a halt at the curb with the sound expensive brakes make when they are applied by men with earpieces. The Whitmore gates opened like something had whispered open sesame into their hinges. Guests in gowns leaned toward the windows and discovered they were extras, not stars. A limousine door swung and my father, William Sterling, stepped onto the gravel in a suit worth more than Clarissa’s centerpieces and less than what his attention costs per minute.

He crossed the space between us and the fury that had carried in his voice over the phone burned off until only worry remained. He shrugged out of his coat—the one the business press likes to photograph him in when he rings the opening bell on Wall Street—and wrapped it around me in a movement I recognized from bicycle falls and dance recitals and a flu when I was nine. “I’ve got you,” he said, soft enough that the cameras would have to decide whether they wanted to risk missing something louder to capture it. Then he turned his head toward the house, toward the doors I had been ejected from, and said in a voice that could open steel: “Which one of you touched my daughter.”

I have watched men pretend to be powerful in Manhattan boardrooms, in Fifth Avenue apartments, in hotels where the carpets muffle guilt. True power does not need to raise its volume. It merely changes the altitude in the room. The police chief from the local department arrived because my father had called him on the drive and asked for a patrol car to ensure no one left during a potential investigation; that is a very legal sentence when such a call comes from someone who sits on half the museum boards in the city. Our security team fanned like a shadow. Five lawyers with files that had been quietly fattening for months moved like men carrying something heavier than paper.

We walked inside to the sound a crowd makes when it is trying to be both classy and curious. The orchestra had set down their instruments but had not left; even artists know when they are about to watch a performance more expensive than any they have ever played. My father took Clarissa’s microphone without asking. You do not ask when the house is both someone else’s and yours already.

“Good evening,” he said, and Greenwich held its breath. “My name is William Sterling.” If money had a doorbell, that was it. There is no American city where his name doesn’t place things into a different order. On the screens where a slideshow of my wedding photos had been making background noise, an image flashed: my father’s face from a magazine cover that used the word Titan and meant it. “This woman,” he said, and pulled me closer, “is my daughter.” No one gasped; money had already stolen their oxygen. “She is my only child and my heir.” Now they gasped.

“She changed her name at eighteen to live without this.” He didn’t gesture at the screen; he gestured at the room. “She wanted love. She got you.” He did not raise his voice. He did not need to. “Tonight, while you filmed her humiliation, while you chose gossip over decency, while her husband chose silence over spine, my team was doing something your family forgot how to do years ago: work.”

He snapped his fingers and the slides flipped. Not news photos. Not collages of charity galas. The feed sharpened, timestamped, in color. The door to Clarissa’s dressing room. Natalie, in jeans and a sweatshirt hours before the party, glancing over her shoulder like a girl in a show who thinks the walls aren’t looking. The jewelry case. The pink diamond. Her hand. Her purse. Another feed: the garden. A rosebush. A small hollow under soil shaped like the kind of lie money grows best. Third clip: Clarissa and Natalie in a sitting room alive with the kind of lamps that try to pass for intimacy. The audio was clear because microphones are inexpensive and planning is cheaper than regret. “We’ll accuse her,” Clarissa said. “We’ll search her in front of everyone.” Natalie, nervous laugh designed for the camera she did not know was already unforgiving: “Are you sure?” Clarissa: “He’ll have to divorce her. We’ll be rid of that little problem.” She did not say my name. The tapes said it for her.

The room changed shape. Gowns were suddenly costumes. Suits were suddenly uniforms for a team no one wanted to be drafted onto. “Would you like to explain?” my father asked, and it landed like a marble dropped into a bowl: simple, heavy, echoing.

Natalie folded in on herself because some people only know how to stand when they are standing on someone else. “I’m sorry,” she said. She looked twelve. “It was Mother’s—” Clarissa’s hand flew toward her, then froze midair under the weight of two hundred eyes that now looked like mouths. “This is a private event,” Vincent tried, because there is a line on every rich man’s bingo card that says if you say private enough times the public might apologize. “Perhaps we can discuss this.” He was already negotiating terms with air.

“Oh, Vincent,” my father said, and the pity in it could have thawed ice. “We passed discussion on our way to consequence.” He nodded once. The slides changed again, and even the wallpaper seemed to hold itself up straighter. Mortgage documents for the estate with Sterling Bank’s logo in the corner. “I bought your mortgage six months ago,” my father said. “Default clauses are dreary reading, but the highlights are clear.” Share purchase agreements for Whitmore Enterprises blinking through the SEC filings like a comet no one had seen because they were all staring at their own reflection. “Sixty-eight percent,” he said. “Majority. I would have told you at your next board meeting.” A screen grab of Clarissa’s trust account with the words account frozen typed beside it. Leases for Natalie’s boutiques with Sterling Real Estate Holdings letterhead. Terminated.

“This can’t be legal,” Vincent said, because he had no idea how much of the law sits in rooms like this one and observes the way money moves. “It’s all legal,” my father said, almost bored. “Unlike assaulting a woman in your home.”

Phones that had been so eager to drink in my pain were now drinking in Clarissa’s unraveling. She tried apology on and it did not fit. “We didn’t know,” she said to my father and to me and to the oxygen in the room that refused to act like this was anything other than what it was. “We’ll apologize. We’ll make it right.” Her voice cracked at the last word because it had only ever been able to say rich.

“Did you stop when she asked?” my father said, and he meant me paused and shaking and begging while two hundred people decided to be audience instead of neighbor. “Did you listen when she told you the truth?” He turned to the police chief and the lawyers and didn’t need to say what would happen next if Clarissa wanted to test how far her last name could carry her past battery and conspiracy.

By then Adrian had reached me. His eyes were wet and wide and his hands were open the way hands open when they have never had to carry something that weighed more than their own benefit. “Mia,” he said, and the word hit the floor with a hollow sound. “Please. Tell him to stop.”

“Do you love me,” I asked, because there are questions that are tests and there are questions that are sentences. “Yes,” he said, too quickly. “I—this—my parents—” “Do you love me,” I said again, and this time I let the room hear the arithmetic of it. “Because love is a verb.” He blinked and swallowed and opened his mouth to explain the physics of his paralysis. “You chose,” I said, because we are always choosing with our mouths, with our backs, with the yaw of our bodies toward or away. “You chose them.”

He cried then, real and late. “I can change.”

“I already did,” I said. A lawyer placed a stack of paper on a table that had been covered two hours ago with macarons that matched the roses. I signed my name the way you sign it when you are done apologizing for the ways you disappoint people who never try to please you. “I am not taking a dollar,” I said to him, to the room, to the girls in bathrooms years from now who will want to know whether it is possible to leave and still feel whole. “I never needed your money. I needed you to stand between me and the people who wanted to eat me alive.” The silence felt honest for the first time all night.

The party ended like a funeral where no one wants to be accused of crying over the wrong person. People left without their gift bags. Greenwich air returned to being Connecticut air instead of theatre oxygen. In the following days, the tabloids did what tabloids do: they bit at the story until the bones showed. “Greenwich Gala Gone Wrong.” “Society Matriarch Accused.” “Billionaire’s Daughter Unmasked.” Page Six used the word humiliated and then the word redeemed and then, once, the word heir in a way that made it sound like a plot twist. In Manhattan meetings where hedge funds share gossip as casually as coffee orders, my father’s name carried the new rumor: he had waited, he had watched, he had purchased not to own but to teach. The stock of Whitmore Enterprises dipped and then slid and then dropped like the last act of a cautionary tale. Vincent’s phone learned a new verb: declined. Clarissa learned what work feels like in shoes that do not have their own names because six months later I saw her at my charity gala checking carbon-tagged coats with a smile that tried to land somewhere between apology and survival. Natalie posted a video about resilience that the internet dunked in ridicule because no one had ever taught her how to be it.

I learned what it is to stand back up and not be made of apology. The morning after Greenwich, my father made me scrambled eggs like he had when I was seven and all my multiplication tables spilled into each other. “You can come back to the company,” he said, which is the way men like him say I will make a space for you the size you deserve. I said yes with my mouth and with the part of me that had always kept books for who tried and who did not. We worked in Manhattan and I earned the right to be vice president of a wing he did not know how to breathe without. I sat in rooms with men twice my age and watched them miscount the number of chairs because they did not see mine at first. I corrected them. I drove across the bridge at night and looked at the skyline that had raised and razed me in the same decade and learned to love it with conditions.

I built something outside the balance sheet: a foundation for women who had been told to stay, to be small, to be grateful for crumbs and quiet, to endure humiliation under chandeliers they couldn’t afford and in apartments they paid for alone. We funded housing and resumes and the soothing of fear. We hired lawyers who say phrases like order of protection like they are not spells but tools. We paid for childcare during job interviews. We put a hotline number on the back of our business cards because sometimes it is easier to tell your story to a stranger. We took checks from men who wanted to be seen giving and spent them on women who wanted not to be seen for a while.

On the night of the gala six months later, the hall on Fifth Avenue hummed with a sound I had never heard at the Whitmore estate: sincerity. Money came in at the edges, sure—money always does—but the center held because what held it were hands. I had chosen a dress that looked like an answer to my younger self’s question: can you be both tender and steel at once. I was greeting a donor when I saw Clarissa behind the coat check counter. She looked like someone who had been rewired by a careful, unsentimental electrician. She waited until the line thinned and asked the colleague beside her to take a step toward the racks. Then she crossed the space to me and stopped with the kind of distance that says it will be my choice.

“I’m sorry,” she said, and the phrase did not smooth itself like she had ironed it. It wobbled. It cost her something. “For all of it. There is not a word that makes it undone.” She was right. There isn’t. “I forgive you,” I said, because forgiveness is not an award the other person earns; it is a weight you decide not to bench-press anymore. Her eyes flooded with the kind of tears that don’t care who is watching.

“But not forgetting,” I said, and her face acknowledged the distinction and felt like a lesson finally learned by a student who had avoided the class for years. “What you taught me,” I said, “is that family is the person who stands between you and the crowd. You are not that. He”—I glanced toward my father, laughing with a city councilwoman and a nurse who had saved more lives than any donor ever would—“is.”

She nodded and looked relieved as if she had been waiting for a sentence and finally received it. “I hope you are happy, Mia,” she said. She meant it. I believed her. She went back to her post and slipped hangers down metal poles to real people with real names who said thank you and meant it.

My father found me near the dessert table (the irony is not wasted: wealth has a sweet tooth). “You all right, baby girl?” he said, and it did not feel like a diminutive. It felt like a reminder: I am still somebody’s child; there is still a lap for the girl who left home and made a home out of herself. “I am,” I said, and for once the sentence did not require a footnote.

He told me he was proud of me. I told him I learned from him. He said he could stand to learn a thing or two from me. We made a small circle that admitted the past and did not admit it to the table. When people ask me whether my father destroyed the Whitmores as vengeance, I tell the truth: he did not destroy them; he stopped subsidizing the cost of their cruelty. They knocked down their own house. He simply owned the land it fell on.

What happened to Adrian? He sells cars now and, according to a mutual friend who sends me updates I do not read until two days later, he is good at it because he is good at convincing people to want what they cannot afford. Once he sent a message that started with I’m sorry and ended with please and I did not open it because that is another kind of forgiveness: the kind where you stop expecting an apology to turn into a time machine.

I have been asked whether the real revenge was the coat check job or the frozen trust or the auction where the Whitmore dining table went for less than a single centerpiece used to cost. Those are merely plot points for people who like stories that print well on gossip pages. Revenge is not dollars deducted. It is breath returned. It is the morning you wake and the first thing you feel is not dread or planning or an agenda to disprove someone else’s miscalculation of your worth. It is the afternoon at your desk when you realize you’ve been working for three hours and did not once imagine the sound of silk tearing. It is a room on Fifth Avenue full of people you chose, eating cake that does not taste like apology.

Sometimes the worst night of your life is the last door you needed to walk through. Sometimes the chandelier light that saw you at your smallest is the same light under which you sign your name to fund someone else’s exit. Sometimes the phone you borrow from a twenty-year-old valet is the only technology you require to reroute a future. Sometimes the man you married in a county courtroom turns away on a marble floor and in the space he leaves the wind rushes in and clears the smoke and you begin, finally, to breathe air that is yours.

Let me end the way those breathless captions always do: by telling you the ending will leave you speechless. Not because a helicopter roared over Greenwich or because mortgage documents bloomed on screens in a room where nobody reads the fine print. The ending that takes your words is quieter. It is a father’s coat over a daughter’s shoulders on a set of stone steps in Connecticut. It is the first night you go to bed and do not replay the rip of a zipper like a siren. It is a woman with a new name going back to the old one and discovering she never left herself in the first place. It is the knowledge that the real prize was never the ring or the ballroom or the membership in a club that would humiliate you for sport. The real prize is standing at a window in Manhattan the next morning, watching the city flex its muscles, and choosing who you will be in it. And then being her.

I am Mia Sterling. I am my father’s daughter because he taught me that power without mercy is cowardice in drag and mercy without boundaries is an invitation to be burned. I am my own person because I learned that love that requires you to shrink is not love; it is property damage. I run numbers and I run meetings and I run baths for myself on Friday nights in a penthouse I bought and paid for with decisions I did not crowdsource. I answer calls from women who say, “I need you,” and I say “Where,” and I mean it.

The Whitmores exist somewhere still, having learned how to live in smaller spaces than their entitlement had prepared them for. Maybe Clarissa counts hangers as a job. Maybe Natalie counts tips. Maybe Vincent counts hours in a day and ties his own bow tie. Maybe Adrian counts the cars he moves and the days without the sound of silk. That is not my business anymore.

This is: the quiet in my chest where a scream used to live, the way my name now sounds when I say it in rooms that belong to me, the astonishment of waking to a life I do not need to explain to anyone. They thought they stripped me that night. What they stripped away was the last illusion that their approval was the rent I had to pay to be in the world. They did not evict me. I left.

If you are waiting for the scene where I drive past the estate and feel a thrill at the sight of an empty driveway, I can offer you something better. Two weeks after the gala, I drove through Greenwich on my way to visit a shelter we’d just funded, and traffic paused outside a gated house that looked like a candle wick without a flame. A woman jogged past pushing a stroller and a man with a leash apologized to a cyclist and a teenager waved at the Amazon driver. The world did what it always does in places like this when a house changes hands: it kept going. I rolled down my window and the air smelled like leaves. I kept going, too.

This is not a plea for you to believe in justice the way a movie believes in it. It is a reminder that sometimes justice looks like logistics. Sometimes it looks like someone showing up who knows how to move paper with the precision of a scalpel. Sometimes it looks like a father who never stopped being poor in his bones, even when his bank account tried to argue. Sometimes it looks like forgiveness that is not a bow to the people who hurt you but a step toward the person you are without them.

On camera, the most spectacular moment was the helicopter light washing that ballroom in noon and making liars squint. Off camera, the most spectacular moment was a loaned jacket around my shoulders while I waited, shivering, for headlights that felt like rescue. The internet loves the first. I live with the second. And the life I stepped into when I stepped out of that dress is the one I choose every morning before my coffee, before my inbox, before my reflection. I was enough then. I am enough now. I will be enough tomorrow when somebody else’s party tries to tell me what I am worth.

The night they called me a gold digger in Greenwich, Connecticut, the United States felt very small: a patch of marble, a ring of phones, a circle of people who mistook cruelty for culture. The morning after, the country felt huge again: a skyline, a highway, a map full of women who would not have to stand alone under a chandelier and try to hold their dress up while their dignity slid to the floor. That is the story. That is the ending worth staying for. Not speechless. Just finally, blessedly, done speaking to those who never listened.