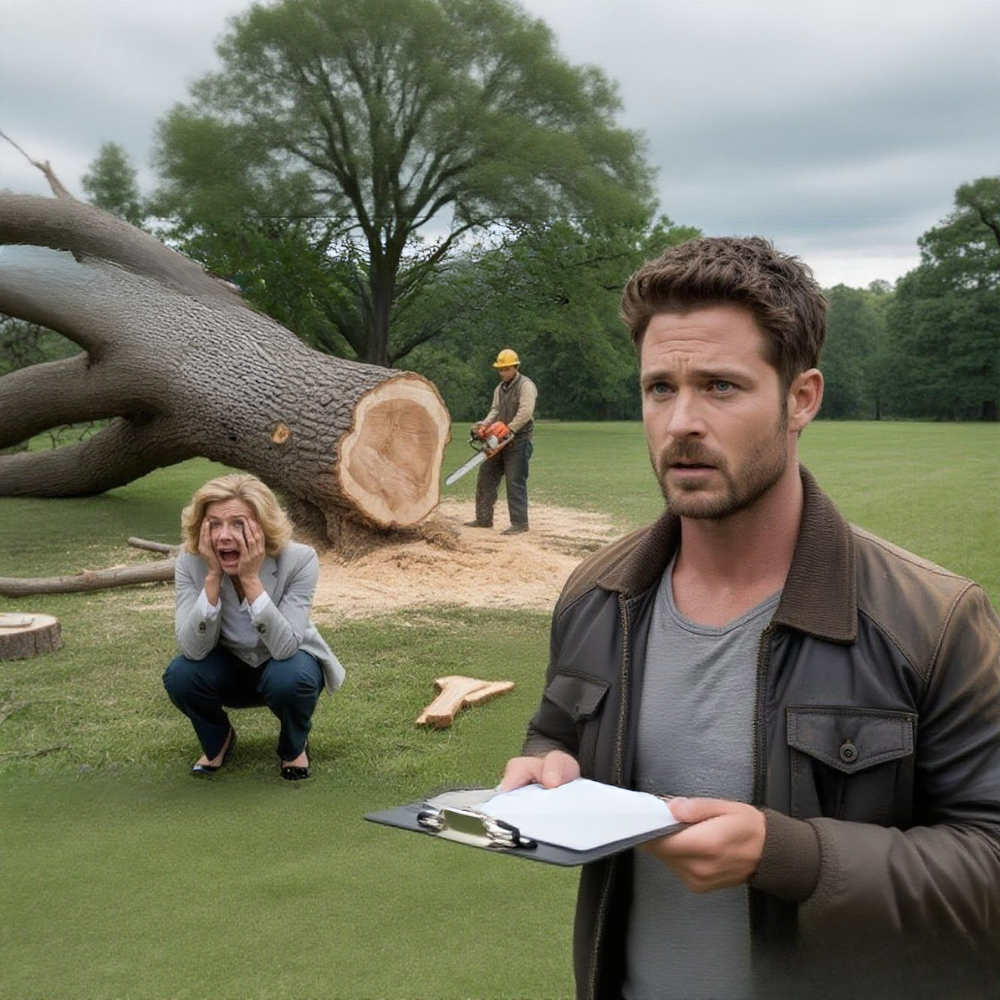

Linda was standing on the stump when I pulled into the driveway, one hand on her hip like she was posing for a magazine cover, the ruins of my family’s white oak sprawled around her like a crime scene.

Sawdust still hung in the Texas air, floating in the late afternoon sunlight over my backyard in Cedar Ridge, a suburban neighborhood just outside Austin. The familiar skyline behind my house looked wrong—emptier, flatter, as if someone had cut a hole out of the sky. Where there had always been a towering crown of branches and leaves, there was now nothing but blue.

She saw my truck, saw me jump out and start running, and she laughed.

“See?” she called, raising her voice over the distant buzz of chainsaws and the clatter of men loading equipment into a trailer parked half up on my grass. “I told you I would fix the problem.”

She was literally standing on top of the stump of my 200-year-old white oak tree, as if it were a stage and this was her victory speech.

She thought she had just cut down a piece of firewood.

She had no idea that the tree she’d just destroyed was a designated heritage species on the Travis County register, protected by Texas state law and local ordinance. And she definitely didn’t know that the penalty for cutting it down without permission wasn’t a slap on the wrist or a few hundred dollars in fines.

When I later handed her the court notice for just over one million dollars, the color drained from her face like someone had opened a tap, and the carefully curated life she’d built for herself in our HOA-controlled paradise started collapsing in slow motion.

But that moment—the one with the legal papers and the gasps and the microphone—came later.

The story really began with that tree.

My name is Alex. I grew up in this house on a quiet cul-de-sac where the mailboxes all match and the trash cans have to be pulled in by 6 p.m. on collection day or you get a passive-aggressive email from the Homeowners Association. My grandfather bought the place in 1980, back when Cedar Ridge was just another growing suburb outside Austin, before the tech boom turned every patch of land into a developer’s dream.

The house itself is nothing special if you only look at square footage: a single-story brick ranch with a two-car garage, a front porch big enough for two chairs and a coffee cup, beige siding, and a roof that always seems ready to need replacing. But to me, it’s a legacy. My grandfather laid the tile in the hallway himself. My grandmother planted the hydrangeas along the side yard. My father patched that crack in the driveway after a hailstorm, swearing the whole time.

The real jewel, though, has always been in the backyard.

Near the fence line, half on the gentle slope that leads down toward the drainage easement, there used to be a white oak tree so massive it looked like it should be standing in front of a courthouse or a university, not behind a modest house in a Texas HOA subdivision. Its trunk took three full-grown adults with outstretched arms to encircle. Its branches spread wide enough to shade most of my yard and a good portion of my neighbor’s.

That tree was older than any house on the block. Older than the streets. Older than the HOA. It had watched this land go from open fields to a few scattered farmhouses to rows of nearly identical homes with manicured lawns.

When I was a kid, we called it the Giant.

My grandfather used to sit under it in the evening, a glass of sweet tea sweating in his hand, and tell me stories about when Cedar Ridge was nothing but scrub and dreams. He’d tip his hat back, look up into the canopy, and say, “That tree has seen more Texas summers than you and I put together, kiddo. We’re just renters in its world.”

When I inherited the house after he passed, I didn’t touch the oak. I trimmed dead branches when the arborist recommended it, installed a security light at the far corner of the yard, and built a small bench in the shade where I could drink coffee before work. I registered the tree with the county heritage program, at my grandfather’s urging before he died. “If anything happens to me,” he’d said, “make sure that tree is protected. People forget themselves when there’s money to be made or views to be cleared.”

I thought he was being dramatic.

Then Linda moved in next door.

She arrived on a Tuesday morning in a convoy of moving trucks and SUVs. The For Sale sign on the house to my right had barely gotten its “SOLD” sticker when gardeners showed up to rip out the perfectly nice shrubs the previous owners had planted and replace them with something more “on trend.”

Linda Martinez was in her late forties, immaculately groomed, and always dressed like she might be called to appear on a local news segment at any moment. She wore yoga pants that had never seen a gym, a blowout that defied humidity, and a permanent expression that hovered somewhere between mild annoyance and restrained superiority.

She moved into Cedar Ridge and, within six months, installed herself as president of the Homeowners Association.

If you’ve never lived in an HOA neighborhood in the United States, especially in a place like suburban Texas, you might not appreciate what that title means to people like Linda. To them, it’s not a volunteer position where you occasionally remind residents to keep their lawns mowed. It’s a crown. It’s a badge. It’s a personality trait.

Linda believed in order. She believed grass should be trimmed to regulation height and watered until it looked like a carpet sample straight out of a Dallas showroom. She believed fences should match. Trash cans should be hidden behind approved screen walls. Holiday decorations should be tasteful and removed by a certain date.

She did not believe in nature.

Oh, she liked the idea of it in a magazine. A strategically placed potted fern. A carefully pruned little tree in a ceramic container on a patio. But real, wild, living nature? Roots that ran deep, branches that reached places you couldn’t control, leaves that fell where they wanted?

No. Absolutely not.

You could see the exact moment the war started.

Linda decided that her backyard “needed a focal point,” as she loudly explained to the contractors who showed up one weekend. That focal point turned out to be a pristine in-ground swimming pool with a stone waterfall, a built-in hot tub, and a deck area that stopped mere inches from the property line we shared.

I watched from my kitchen window as they dug, poured concrete, installed pumps, and tiled the edges in shades of blue and gray. I didn’t say anything. It was her land. Her money. Her business.

The first conflict came with autumn.

We don’t get the kind of dramatic fall colors in Texas that you see on postcards from New England, but the seasons change all the same. The air cools just enough. The light shifts. And the trees, including my white oak, start letting go.

The Giant’s leaves would turn from deep green to a muted gold, then drift down in lazy spirals when the wind picked up. Most fell into my yard. Some landed on the slope. A few, inevitably, caught the breeze just right and floated over the six-foot privacy fence into Linda’s brand-new pool.

The first day her pool company did a cleaning, I heard her shouting through the open windows.

“This is unacceptable!” she snapped at the young technician skimming her water. “I pay a lot of money for this pool, and I want it spotless. I shouldn’t have to deal with my neighbor’s mess.”

The tech, to his credit, stayed polite. “Ma’am, it’s just a few leaves. It happens everywhere. We’ll clean them out.”

To Linda, though, this wasn’t “just a few leaves.” This was the beginning of what she saw as an invasion.

She started sending emails.

Subject: Leaves

Subject: Tree Debris

Subject: Violation of HOA Cleanliness Standards

All of them came through the official Cedar Ridge HOA portal, stamped with her digital signature as president. They were always couched in formal language, full of phrases like “detrimental impact on neighboring property enjoyment” and “failure to maintain tree in a manner consistent with community standards.”

I responded once, calmly, explaining that the white oak was on my property, registered as a heritage tree in the county, and that I had already consulted with an arborist to ensure it was healthy and properly maintained.

I attached a copy of the county’s letter.

She didn’t reply.

At least, not by email.

She waited until she was good and mad.

It was a Wednesday evening in late October when the pounding started.

It sounded like someone was trying to break the door down. I was in the kitchen, spoon halfway between the pot and my bowl, when the banging rattled the windows.

I set the spoon down and opened the door.

Linda stood on my front porch, her face flushed an alarming shade of red, hair slightly frizzed from the damp Texas air. She was clutching a Ziploc bag in one hand.

She thrust it toward my chest.

“Do you see this?” she demanded.

I looked down. Inside the bag were three oak leaves. Three.

“Good evening, Linda,” I said slowly. “Can I help you with something?”

“That stupid tree of yours,” she snapped, ignoring my attempt at civility. “Three leaves. I found three leaves in my skimmer basket today. Three. Do you have any idea how disgusting that is?”

I blinked. “Three leaves,” I repeated. “In your outdoor pool. In October. In Texas.”

She glared. “Don’t get smart with me. I want that thing cut down immediately.”

I felt something in my chest tighten.

“Linda,” I said, keeping my voice even. “That tree is more than two centuries old. It’s on my property. And more importantly, it’s registered with Travis County as a heritage tree. I literally cannot cut it down. It’s protected by law. Even if I wanted to, which I don’t, I’d have to go through a whole permit process and prove it was diseased or dangerous. And it isn’t either of those things.”

“Don’t quote laws to me,” she said, stepping closer. I could smell her perfume, sharp and expensive. “I am the HOA president. I make the rules here. I can write you up for this. I can fine you. I can put a lien on your house.”

“The HOA can enforce its covenants,” I said calmly, “on things actually covered by the covenants. The white oak is not one of them. You don’t have the authority to override state and county environmental protections.”

Her eyes flashed.

“If you don’t get rid of that tree,” she hissed, “I will hire a crew and rip it out by the roots myself. You think I’m joking? Watch me.”

I looked her dead in the eye and felt something cold settle in my stomach.

“Linda,” I said. “If you, or anyone you hire, steps one foot on my land to touch that tree, I will call the police and report it as trespassing and vandalism. Do not touch my tree.”

She let out a short, humorless laugh. “We’ll see,” she said. “You’ll be begging me to help you when your property is in violation and your resale value tanks because your yard looks like a forest instead of a proper suburban home.”

She turned on her heel and stalked off my porch, muttering under her breath about “ungrateful neighbors” and “people who don’t understand community standards.”

I watched her go, the screen door creaking closed behind me. My heart hammered. My hands shook. Not because I was afraid of her, exactly, but because I knew people like Linda. People who genuinely believed a title made them untouchable. People who thought “HOA president” outranked state law.

I told myself that was the end of it.

I told myself that even she wouldn’t be reckless enough to commit a felony over a few leaves in a pool.

I was wrong.

Three days later, I was sitting in a conference room at work in downtown Austin, halfway through a budget meeting, when my phone buzzed on the table. I glanced down.

BACKYARD CAM – MOTION ALERT.

It wasn’t unusual. Sometimes it was just a squirrel. Sometimes a stray cat trying to treat my fence like part of an obstacle course. I swiped the notification away without thinking and went back to the numbers.

If I had opened the app then and there, I would have seen everything happening in real time. The truck backing up to my fence. The men hauling chainsaws out of the bed. Linda standing in the corner of my yard with her arms crossed as if supervising a renovation project.

By the time I drove home that afternoon, sun hanging low over the highway, the pit in my stomach had started before I even turned onto our street.

Something felt wrong.

I couldn’t have explained it. The houses looked the same. The mailboxes. The manicured lawns. But as I approached my driveway, a shadow that had always been there… wasn’t.

I parked too fast, gravel crunching under my tires, and practically jumped out of the truck before the engine fully shut off.

My feet pounded the path along the side of the house. I rounded the corner into the backyard and stopped so abruptly my knees nearly folded.

For a moment, I couldn’t breathe.

The Giant was gone.

Where the massive trunk had once risen, there was now empty sky, a raw, jagged stump, and chaos.

The trunk lay on its side across my lawn, severed cleanly at the base. Branches were scattered in every direction, some stripped of leaves, some still heavy with them. The grass was buried under a layer of sawdust that looked like a strange kind of snow, pale and soft, clinging to my shoes as I stumbled forward.

The air was thick with the smell of fresh-cut wood. A smell I usually loved, the scent of a project, of work done with care. Now it was overpowering, nauseating.

The white oak that had shaded three generations of my family, that had survived storms and drought and development, had been cut down in a single afternoon.

It felt like I’d turned the corner and found a family member lying injured on the ground.

And there, in the middle of it all, was Linda.

She was standing next to the stump, one foot propped casually on the rough surface like a hunter posing with a trophy. Her phone was pressed to her ear.

“Yes, I finally got rid of the eyesore,” she was saying, laughing. “You should see it. The yard looks so much bigger now. And my pool? It’s going to stay spotless. No more fishing leaves out every morning. Honestly, I don’t know why he didn’t thank me before.”

She turned at the sound of my footsteps and spotted me.

Her smile widened into something smug.

“Oh, hey, Alex,” she said, covering the phone’s receiver with her hand. “You’re welcome, by the way. I told you I take action. Your yard was a mess with that thing. Now it looks ready to actually add value to the neighborhood. I’ll send you the bill for the crew. It wasn’t cheap, but it’ll be worth it.”

My vision narrowed.

My pulse pounded in my ears.

Every instinct I had screamed at me to shout, to demand what she thought she was doing, to physically drag her off the stump and off my property. I could feel the words rising in my throat, hot and furious.

I swallowed them.

I forced my hands to unclench.

I forced myself to breathe in through my nose, out through my mouth, the way my grandfather had taught me when I was a kid who wanted to throw a punch at the first kid who insulted me.

Because in that moment, looking at Linda’s self-satisfied expression, hearing her brag about what she’d done, I realized something important:

The more I yelled, the more I raged, the more she would enjoy it.

And the calmer I was, the more dangerous I became.

Without saying a word, I pulled my phone out of my pocket and opened the camera.

I began to record.

I filmed the stump. The pulverized grass. The scars near the base where you could see how cleanly the chainsaw had cut through living wood.

I panned up to Linda, capturing her standing with her foot on the stump, her phone still pressed to her ear, her smug smile still in place.

“Um, excuse me?” she said, lowering the phone a little. “What are you doing?”

I said nothing.

I stepped around her, careful not to touch her, and filmed the path the crew had taken. They’d driven their truck up over the curb, onto my side yard, leaving deep ruts in the soil. Bits of bark and leaves littered the path. A few smaller branches were still tangled near the fence where they hadn’t bothered to clean up yet.

I walked back toward the house. Linda called after me.

“What’s the matter, Alex?” she taunted, her voice suddenly sharper. “Cat got your tongue? You should be thanking me. I just raised your property value. Next time, listen to your president when she tells you something needs to be done.”

I stopped halfway to the back door and turned slightly, not enough to give her my full attention, but enough that she knew I’d heard.

Then I put my phone away and walked into my house without another word.

Silence is the loudest weapon.

I shut the door, leaned against it for a second, and let the shaking start.

My hands trembled so hard I nearly dropped the phone. My chest felt like someone had dropped a cinder block onto it. I pressed the heels of my palms to my eyes until I saw stars.

Then I moved.

Not to call the police. Not yet.

Instead, I opened the app for my security cameras.

The footage from earlier that afternoon was sitting there, waiting.

I tapped on the thumbnail for “BACKYARD.”

There it was: the time stamp, the truck backing up, the men hopping out, glancing nervously around. Linda leading them through her side gate and then gesturing imperiously toward my fence.

They climbed over like it was nothing. No attempt to contact me. No knock on the door. No permission asked.

I watched the first cut, my stomach clenching as the chainsaw bit into the bark I’d touched a thousand times. I watched Linda standing off to the side, arms folded, nodding in approval.

Every second of it was recorded in crystal-clear HD.

When the rage bubbled up again, hotter than before, I pushed it down under the cold, focused part of my brain that had gotten me through every bad day I’d ever had.

There was a time for anger.

This was the time for precision.

I sat at my kitchen table, pulled out a notebook, and wrote three names:

County Heritage Tree Program Director.

Certified Arborist.

Property Attorney.

Then I started making calls.

The arborist came first.

His name was Mark. He’d been the one who’d helped my grandfather register the white oak as a heritage tree years earlier. When I told him what had happened, there was a long silence on the phone.

“Are you sure it’s gone?” he finally asked, as if there was some way I might be mistaken, as if a 200-year-old tree could simply be misplaced.

“I just watched the video,” I said. “And I’m staring at the stump right now.”

“I’ll be there tomorrow morning,” he said. “Don’t let anyone touch anything else until I get there. No cleanup. No moving branches. Leave it exactly as it is.”

“Okay,” I said.

Next, I called an attorney.

His name was David Howell. He’d been recommended by a coworker who’d gone through a nasty boundary dispute with a neighbor and come out on top, thanks in large part to David’s meticulous work.

When I explained what had happened, he asked, “Do you have security footage?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Do you have previous documentation of the tree’s protected status?”

“Yes.”

“Do you have any written communication from her about the tree?”

I thought of the emails. The HOA portal messages. The Ziploc bag with three leaves.

“Yes.”

There was a pause, followed by a low whistle.

“I’d like you to send me everything,” he said. “Videos, emails, that heritage designation letter from Travis County, any photos you have of the tree before this week. Then I want you to take a deep breath, try to get some sleep tonight, and tomorrow we’ll start building something she’s not going to see coming.”

“Are we talking about suing her?” I asked. “Or pressing charges?”

“We’re talking about both,” David said. “In Texas, we have specific statutes that deal with this kind of thing. Timber trespass. Heritage tree protections. There’s a reason we call it ‘tree law’ in my line of work. People think they’re just cutting firewood until they see the numbers.”

He paused.

“And based on what you’ve told me,” he added, “your HOA president may have just turned a few leaves in a pool into the most expensive mistake of her life.”

The next day, Mark arrived with a clipboard, measuring tape, and a grim expression.

He walked my yard slowly, documenting everything. He took photos from every angle. He measured the diameter of the stump at breast height, counting the rings with his fingers where the chainsaw had left them exposed. He scraped samples, checked for disease (there was none), and took careful notes.

“This tree was healthy,” he said, straightening up. “Solid. No internal decay. It could have stood for another fifty, maybe a hundred years with proper care. There was absolutely no valid reason, from an arborist’s standpoint, to remove it.”

He measured the slope near the fence line, looking at the bare earth where roots had once held the soil in place.

“See this?” he said. “With the tree gone, you’re going to have erosion issues. Especially when storm season hits. That oak was acting like a natural retaining system. Now, without it, you’re going to need a structural wall to prevent this whole section from sliding during heavy rain. That’s not cheap.”

He left with a full report promised within forty-eight hours.

David called me as soon as he had it in hand.

“Alex,” he said, and I could hear something almost like excitement in his voice. “You might want to sit down for this.”

I did.

He started walking me through the numbers.

“First,” he said, “we have the basic value of the tree itself. Because this wasn’t just some sapling. This was a mature, healthy, white oak, registered as a heritage specimen with the county. In landscaping terms, a tree like that is functionally irreplaceable. You can plant ten new trees, but you can’t buy those two centuries back.”

“I understand,” I said quietly.

“To calculate replacement cost,” he continued, “we look at species, health, size, placement, and the role it played on the property. Mark’s report indicates a base appraisal of around eighty thousand dollars for this tree alone.”

“Eighty…” I swallowed. “Eighty thousand dollars. For a tree.”

“In your state,” David said, “when someone trespasses on your land and cuts down trees maliciously or knowingly, we have a statute for timber trespass. Under that, the court can award treble damages.”

“Treble?” I asked.

“Triple,” he said. “Three times the assessed value. Because the law recognizes that people might otherwise calculate that paying replacement cost is just the price of getting what they want. Treble damages are meant to send a message: don’t touch what isn’t yours.”

He didn’t bother to muffle the tap-tap-tap of his fingers on his calculator.

“That brings us,” he said, “to two hundred and forty thousand dollars. Just for the tree.”

My stomach flipped.

“And we’re not done,” he added.

“Of course not,” I muttered.

“Because the tree was on a slope,” David said, “and its root system was stabilizing that slope, the arborist has noted that you are now at increased risk of erosion and soil movement. In other words, without that tree, your land could literally start slipping during heavy rain events. To remediate that, you’ll need a proper engineered retaining wall. Mark’s estimate for that is around fifty thousand dollars.”

I heard the calculator again.

“Now we add in,” he went on, “the cost of removing the massive trunk and debris that she left behind, because you can’t exactly drag a 200-year-old oak to the curb for regular pickup. That’s going to run you another ten to fifteen thousand, depending on the company and the method they use. We’ll call it twelve for now.”

Tap. Tap. Tap.

“So,” he said, “we have eighty thousand times three, plus fifty for the wall, plus twelve for removal. Then we factor in emotional distress—yes, that’s a real thing, especially when we’re talking about something with deep sentimental value and documented heritage designation—plus legal fees, plus punitive damages because this wasn’t an accident. She didn’t mistakenly trim a branch that crossed the property line. She hired a crew, trespassed, and chopped the entire thing down after you explicitly warned her not to.”

He slid the paper across his desk to me when I met him in person later that afternoon.

In neat handwriting at the bottom, circled, was the total.

$1,027,000.

I let out a low, disbelieving whistle.

“Do you think a court will actually award that?” I asked.

David smiled—not a warm smile. A sharp one.

“With the video we have?” he said. “With her on record, on your security camera and in your own recording, bragging about hiring the crew and ‘fixing the problem’? With Mark’s report and the county’s heritage designation? I’d say we have a very strong case. Judges don’t love people who act like the law doesn’t apply to them.”

He leaned back in his chair.

“The best part,” he added, “is that you don’t even have to shout. The paperwork will do the shouting for you.”

I traced the number with my eyes again.

“So what do we do next?” I asked.

He folded the file closed with a satisfying thump.

“Next,” he said, “we serve her.”

The timing worked out almost too perfectly.

The monthly Cedar Ridge HOA meeting was scheduled for Sunday morning in the community clubhouse, a beige building near the entrance of the subdivision with a small conference room, coffee urns, and rows of metal chairs. Residents were strongly “encouraged” to attend to stay updated on neighborhood policies, hear financial reports, and listen to Linda remind everyone of the importance of matching mailbox colors.

It was also, conveniently, the place Linda liked to stand at the front of a room with a microphone and feel important.

David, never one to miss an opportunity for impact, suggested we serve her there.

“Publicly?” I asked.

He raised an eyebrow. “She trespassed publicly. She cut down a protected tree in broad daylight, in full view of anyone who glanced out their window. She used her title as HOA president to threaten you. You owe her nothing in terms of privacy. And it will make it harder for her to spin the story if half the neighborhood hears the truth at the same time.”

So, Sunday morning, I put on a clean shirt, grabbed the legal binder David had prepared, and drove the short distance to the clubhouse.

The parking lot was already half full. Inside, the folding chairs were set up in neat rows facing a long table at the front where Linda and the other board members sat. A plastic banner reading CEDAR RIDGE HOA – COMMUNITY FIRST hung crookedly behind them.

Linda was in her element.

She stood at the lectern, microphone in hand, flipping through a stack of papers.

“…and we’ve had several complaints about trash cans being left out past 6 p.m.,” she was saying when I stepped into the back of the room. “Please remember, everyone, that part of maintaining our property values is keeping our neighborhood looking its best. If we start looking like some random street in Austin instead of a planned community, buyers will go elsewhere.”

A few people chuckled dutifully.

I closed the door behind me with a soft but audible thud.

Heads turned.

Some of my neighbors recognized me and nodded cautiously. Others glanced from me to the thick binder in my hands and then back to Linda, as if sensing that something, finally, was about to happen.

Linda followed their gaze.

Her eyes landed on me and narrowed.

“Oh, look,” she said into the microphone, her voice taking on a mocking lilt. “It’s Alex. Did you finally come to pay me for the tree removal service? I’m sure the crew would appreciate being compensated for cleaning up that jungle you had back there.”

A few people shifted in their seats, uncomfortable.

I walked down the center aisle, the binder tucked under my arm. My heart pounded, but my steps were steady.

“No,” I said, my voice carrying in the room without the mic. “I’m here to pay you back.”

A ripple went through the crowd.

I reached the front table and set the binder down with a heavy thump directly in front of her. The sound made the microphone squeal.

Linda recoiled slightly, then leaned forward, trying to keep her expression composed.

“What is this nonsense?” she asked, forcing a laugh. “Are you filing a complaint? You can submit that through the proper portal like everyone else. We have procedures—”

“You have been served,” I said, loud enough for everyone in the room to hear.

I opened the binder to the first page and slid the stack of documents toward her. On top was the official notice of civil action, stamped by the court.

She picked it up with the casual disdain of someone accustomed to dealing with petty grievances.

Her eyes dropped to the first paragraph.

The laughter stopped.

As she read, line by line, the color drained from her face in a way I had only previously seen in movies. One moment she was pink and smug; the next, she was the color of paper, her lips pressed together so tightly they all but disappeared.

Her hands began to shake. The pages rattled.

“Th-this says…” she stammered, her voice catching on the words. “This says… one m… million dollars. Are you insane?”

She looked up at me, eyes wide, voice rising in pitch. “It was just a piece of wood!”

Behind us, someone in the second row muttered, “Oh, boy.”

I turned to the microphone, gently moved it closer to my mouth, and spoke calmly into it.

“It was a protected heritage tree registered with Travis County,” I said. “It was over 200 years old. It was healthy. It was on my property. And it was cut down after you were explicitly told not to touch it.”

I flipped to one of the photos in the binder and held it up so the front rows could see: Linda, standing on the stump, phone in hand, grinning.

“On this date,” I continued, “you hired a crew, directed them onto my land without my permission, and had the entire tree removed while I was at work. That’s not ‘cleaning up.’ That’s trespassing and willful destruction of protected property.”

I turned back to her.

“Under Texas law,” I said, “you committed a felony. This lawsuit seeks the appropriate damages.”

“A… a lien?” she said, stumbling over the word. “This says you’ve put a lien on my property. On my house. You can’t do that.”

“Yes,” I said. “We can. And we did. Until the damages in this lawsuit are paid, your house, your car, and that swimming pool you’re so proud of are encumbered by this judgment.”

The room had gone silent. You could have heard a pin drop.

Linda’s gaze darted to the other board members like she was looking for a life raft.

“Help me,” she said, her voice breaking. “The HOA will cover this, right? I did it for the neighborhood. For our property values. You all wanted that tree gone too. You complained. You said it was messy. You said—”

The treasurer, a soft-spoken man named Rob who usually stayed in the background, stood up.

“Absolutely not,” he said, surprising everyone. His voice was stronger than I’d ever heard it. “The board never voted on removing that tree. There was no motion, no approval. You acted on your own. You hired a crew on your own. You went onto his property without authorization. The HOA is not liable for your actions.”

A murmur went through the crowd.

“He’s bluffing,” Linda said, desperate now. “He has to be. This is ridiculous. You can’t sue someone for cutting down a tree. It was ugly! It was dropping things in my yard. It was—”

“Protected by state and county law,” I repeated. “And registered as a heritage specimen. In case anyone’s curious, the documentation is in Exhibit B.”

I tapped the binder.

Linda looked from me to the pages in front of her, to the neighbors staring, to the board members shifting in their chairs. Her composure slipped like a mask loosening. Tears welled in her eyes. She sank down into her seat, the papers clutched in her fists.

Her voice, when it came, was small.

“I didn’t know,” she whispered.

“Yes,” I said quietly. “You did. You just didn’t care.”

The aftermath wasn’t instant, but it moved faster than I’d expected.

David filed the full suit. The county, already displeased by the destruction of a registered heritage tree, opened its own investigation. The local news picked up the story—not in a screaming headline sort of way, but as one of those “know your rights as a homeowner” segments they like to run during sweeps, complete with an expert talking calmly about tree law in Texas.

Linda tried to fight it at first.

She hired a lawyer who promised to “make this go away.” She told anyone who would listen that I was exaggerating, that the tree had been “sick” and “dangerous,” that she’d taken action because the HOA “couldn’t afford the liability” of it falling.

Unfortunately for her, security cameras don’t lie. Neither do arborist reports.

In court, the footage played on a large monitor: Linda opening her side gate, pointing toward my fence, men climbing over, chainsaws roaring to life. Then the second video, the one I’d taken on my phone: Linda standing on the stump, talking about getting rid of “the eyesore” and sending me the bill.

The judge watched in silence.

When it was Linda’s lawyer’s turn, he tried to argue that she’d acted out of concern for the neighborhood, that she’d misunderstood the legal protections, that she’d thought her authority as HOA president gave her some leeway.

The judge, an older man with a patient face and little tolerance for nonsense, lifted his brow.

“Ms. Martinez,” he said, “you were informed, verbally and in writing, that this tree was protected. You were warned not to touch it. You proceeded anyway. That’s not a misunderstanding. That’s willful disregard.”

In the end, the court didn’t grant every penny of our initial calculation. Judges almost never do.

But they came close.

Between treble damages for the tree, compensation for the retaining wall and removal costs, legal fees, and punitive damages, the final judgment hovered just under one million dollars.

Linda did not have a million dollars lying around.

She appealed. She lost.

She tried to negotiate. David agreed to a payment plan of sorts, but even that required more liquid assets than she had.

That’s when the real consequences began.

To satisfy the judgment, she had to liquidate what she could. That meant putting her house on the market, the very house she’d tried so hard to make a showpiece of Cedar Ridge. The listing photos were careful not to show the bare patch of soil where the oak had once stood, the new retaining wall hugging the property line like a scar.

In HOA gossip circles, the story spread.

Some people called me ruthless behind my back. Others, often the ones who’d also felt Linda’s heavy-handed enforcement of the rules, sent me quiet messages of support.

“Good for you,” one neighbor wrote. “She’s been terrorizing people over trash cans for years. Maybe this will finally humble her.”

Tyler, the teenager from two doors down who used to climb the oak when he was little, thanked me in person.

“It was wrong what she did,” he said, scuffing his shoe on the sidewalk. “That tree was… I don’t know. It was part of the neighborhood. I’m sorry.”

I told him it wasn’t his fault.

When the sale finally went through, the settlement money transferred.

I didn’t buy a sports car. I didn’t take a lavish vacation. That had never been the point.

I paid for the retaining wall. I paid Mark for his work. I covered David’s fees without blinking.

Then I stood in my backyard, in the space that felt unnaturally bright without the old oak’s shade, and thought about what came next.

You can’t replace a 200-year-old tree.

But you can plant a future.

With a portion of the settlement funds, I bought ten white oak saplings from a reputable nursery, each one about eight feet tall. I planted them along the property line, some on the slope where the old roots had once dug deep, some further back to create a staggered canopy over time.

It would take years before they cast real shade. Decades before they approached anything like the majesty of the Giant.

But one day, some kid in Cedar Ridge—or whatever the neighborhood would be called then—might sit under one of those trees and feel the same sense of calm I’d felt under the original.

The rest of the money went into savings, into repairs my grandfather had never gotten around to, into a fund for the next unexpected catastrophe life might throw my way.

As for Linda, word got around that she’d moved into a small apartment complex in another part of town. No yard. No pool. No trees. No HOA presidency to use as a crown.

I didn’t gloat. Not out loud.

But every time I walked past the new saplings and felt the first hint of their shade on my skin, I thought of her standing on that stump, laughing as she talked about getting rid of an “eyesore,” and I felt a quiet sense of balance settle over everything.

Karma doesn’t always show up right away.

Sometimes it arrives like a storm, sudden and overwhelming.

Sometimes it arrives in the form of a quiet legal notice slid across a table.

Sometimes it takes the shape of ten young trees, rooted where one old survivor once stood, their leaves catching the Texas sun like green pieces of glass.

Linda thought she was above the law. She thought her title made her untouchable. She thought she could walk onto someone else’s land and rewrite the landscape to fit her idea of perfection.

Instead, she learned a very expensive lesson that plenty of homeowners in the United States should probably take to heart:

You can control the color of your neighbor’s mailbox in an HOA.

You cannot, no matter how important you think you are, put a price tag on a living thing that was protected before you ever showed up.

And if you try?

Well.

Sometimes the tree fights back.