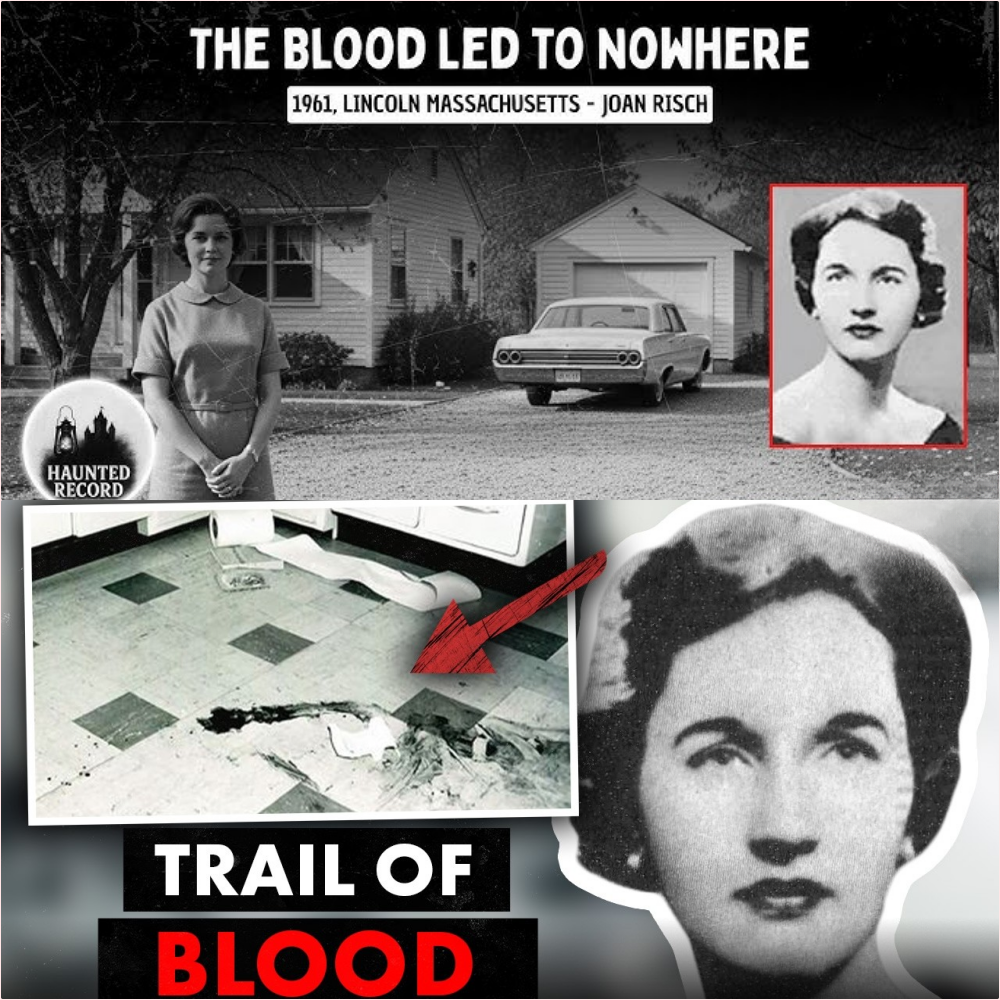

The first streak of red didn’t look like blood—at least not to a four-year-old. It looked like paint. Bright, startling, splashed across the quiet kitchen of a Lincoln, Massachusetts home, the kind of scene that shouldn’t exist in broad daylight. And yet there it was, a smear glistening under the weak October sun as little Lillian Risch pushed open her neighbor’s screen door and whispered the sentence that would haunt the town for decades.

“Mommy is gone… and the kitchen is covered in red paint.”

That one line cracked open the silence of 1961 suburbia like a stone through glass.

Mrs. Barker followed the child back across the neat yards of their cul-de-sac, expecting a mess, a spill, maybe an accident. What she walked into instead was a strange, disorienting tableau—a home that felt both recently lived in and violently interrupted, as if someone had hit pause on a life and walked away with the remote.

Joan Risch, a 31-year-old mother of two, was nowhere in sight.

The kitchen looked wrong immediately. A single bloody thumbprint on the wall. The heavy black telephone yanked off its mount, its receiver buried halfway down a kitchen trash bin that had been dragged out unnaturally toward the center of the floor. The phone book lay open to the emergency page, its corner stained.

The floor carried smears—not splashes, not puddles, nothing that screamed cinematic violence—just the unmistakable evidence of someone stumbling, leaning, trying to stay upright, someone who was moving through pain rather than lying in it.

Two-year-old David’s tiny coveralls lay rumpled nearby, streaked with the same red, as if someone had grabbed the fabric in desperation, pressed down, attempted to clean something… or hold something. The toddler himself was unhurt. Clean. Confused. Quiet.

In the doorway to the living room, another stain. And leading up the stairs, a dotted trail as if Joan had climbed them searching for help, or searching for something she couldn’t find.

The house felt wrong in that way crime scenes often do—like the air had been disturbed, pushed aside by an invisible presence that lingered in the corners. Not broken windows. Not overturned furniture. Something subtler. Something chilling.

Outside, the October sky was unusually bright, the trees rustling in a wind too gentle to explain the storm gathering inside the Risch home.

Police arrived fast. Lincoln wasn’t the kind of Massachusetts town where mothers vanished. It was safe, postcard-clean, a place where people left doors unlocked and waved across their lawns. Before long, patrol cars were parked along Old Bedford Road, attracting neighbors onto porches, then sidewalks, then front lawns, whispering the same question:

What happened to Joan?

Her husband, Martin, was in New York on business. Verified. Accounted for. Hours away. There was no sign of forced entry. No sign of a prolonged struggle. No screaming neighbors had heard. No tire marks. No broken glass. No missing valuables. Nothing stolen. Nothing obvious.

The kind of nothing that means everything.

The police stepped carefully through the house, cataloging details. The master bedroom showed faint traces of blood near the bureau. The children’s room had a smear on the hallway floorboards. But there was no scene upstairs. No collapse. No signs she’d stopped, or sat, or laid down.

A single direction kept pulling the trail forward—back downstairs, through the kitchen, across the gravel driveway, toward Joan’s pale blue car.

The vehicle itself sat untouched. Unmoved. Clean interior. Blank exterior except for three puzzling spots: a faint smear near the right rear fender, another near the windshield, and one dead-center on the trunk—the kind of mark someone might leave when bracing themselves, or being forced back.

And then the trail stopped. Full stop. As if Joan evaporated the moment she stepped past the car.

The news spread by sundown. Officers canvassed the quiet roads. Search teams formed quickly, fanning out through woods, ditches, open fields, creeks. Helicopters buzzed overhead. Volunteers scoured Lincoln well into the night.

Nothing.

Just a thumbprint. A trail. A missing woman. And two children who had watched only pieces of something too large to understand.

By the next day, newspapers across Massachusetts ran the story. “LINCOLN MOTHER VANISHES,” the Boston Globe declared. The FBI stepped in. The case became national almost overnight—not because of violence, not because of spectacle, but because of the impossible puzzle it presented.

Joan Risch didn’t just go missing.

She walked into a mystery that felt staged, deliberate, and deeply wrong.

But the strangest part was how ordinary her day had been until the moment it wasn’t.

That morning, Joan woke early, the kids chattering in their pajamas as she fixed them breakfast. Her husband kissed her goodbye before his business trip. She ran errands. Made polite small talk with a bank manager. Kept a dental appointment where she chatted with the receptionist. Came home, put the baby down for a nap, opened the door for a salesman, talked with her neighbor Mrs. Barker as their kids played in the yard.

Normal. Cheerful. Mundane.

At 2 p.m., Joan walked Lillian and the Barker children back across the lawn, waving from the driveway as if she’d be right back.

Fifteen minutes later, Mrs. Barker glimpsed her again—moving quickly through her yard, holding something red, heading toward the trees. But from a distance and through a screen of autumn foliage, details blurred. It could’ve been groceries. A toy. Laundry. Or something else entirely.

By 3:45 p.m., Lillian was being dropped back at home. There was no chaos. No noise. No warning. Nothing seemed off.

And then the silence became proof something had gone terribly wrong.

What haunted detectives almost immediately were the timing overlaps. A teenage boy had seen a strange car in the Risch driveway around 3:30 p.m. Ten minutes later, a different neighbor saw a car—possibly the same one—backing out. The descriptions were vague, but consistent: dark-colored, unfamiliar, definitely not Joan’s.

Just after 4 p.m., Mrs. Barker opened her back door to find Lillian standing there clutching her dress, saying the line that would echo through every police report for the next six decades.

“Mommy is gone.”

Investigators retraced Joan’s final walk over and over, trying to understand the sequence. The kitchen suggested someone wounded had been moving under their own power—stumbling, bracing against walls, attempting to stand upright. But the blood volume wasn’t catastrophic. It wasn’t the kind associated with a fatal assault. It looked like injury, not execution.

Yet Joan didn’t reappear. No hospital reported an unidentified woman arriving with injuries. No bus station, no airport, no taxi company, no train line logged someone matching her description.

Instead, witnesses began calling in sightings from across Massachusetts. A pale woman walking unsteadily near Route 128. A confused woman matching Joan’s description at a Boston bus terminal. A driver who swore he’d dropped her off hours after the disappearance.

But sightings multiply in every unsolved mystery. People see what they fear. Or what they hope.

And then came the detail that changed everything—the reason this case would never again be seen as a simple abduction or random attack.

Police went to Lincoln Public Library.

Joan had checked out twenty-five books in the months leading up to her disappearance. Many were novels, yes. But many were about women who vanish deliberately—women who fake injuries, fake deaths, start over in new towns with new names.

Some were about amnesia.

Some about secret escapes.

Some about reinventing oneself so completely the old life becomes a ghost.

And the strangest part?

Friends said she never spoke of wanting to leave. She adored her children. She maintained routines religiously. She prepared for emergencies like a drill sergeant. She was meticulous, thoughtful, precise.

Not a single person reported she was depressed, trapped, or desperate.

Yet she consumed stories about disappearance—methodical, researched, intentional disappearance.

Was she studying? Escaping? Fantasizing? Coping? Or was she simply a curious reader who happened to vanish into a story she never meant to live?

Police found her last book open on the table, pages fanned as if she had just set it down.

The Immortal Queen. A woman whose life is defined by betrayal, reinvention, and the power of myth.

Over the years, the theories hardened into three main branches: a staged disappearance, an abduction, or an accident. But in those first hours—those first frantic, electric hours—investigators had no such clarity. Only panic. Only the surreal vision of a blood-marked kitchen and a house that felt abruptly, unnervingly hollow.

There were still leads to chase.

Sightings to verify.

Interviews to conduct.

Neighbors to re-question.

Timelines to reconstruct.

And the strangest, most unsettling clues were yet to come.

Because as detectives widened their search, they discovered something about Joan Risch they could not ignore.

She had vanished before.

Not physically. But emotionally. Historically. As a child, Joan had been forced to rebuild her entire identity after a tragedy so severe it had reshaped her life.

And suddenly, her disappearance no longer looked simple at all.

It looked like the continuation of a story that began long before October 24, 1961.

A story Part 2 will plunge into deeper—her past, her psychology, the sightings, the mysterious cars, the contradictions, and the theory that even after sixty years refuses to die.

The theory that Joan didn’t just disappear.

She walked away.

What investigators didn’t understand—not at first—was that Joan Risch had already lived one disappearance long before 1961. She didn’t broadcast it. She didn’t dramatize it. She didn’t even speak about it much. But the truth sat in her history like an old bruise, faint but unmistakable once you looked close enough.

Before she was Joan Risch, suburban mother of two, she was Joan Natress, a little girl in New Jersey whose world burned—literally—when she was just nine years old. A fire consumed her family home. Both her parents died. The life she knew went up in smoke, replaced by the sterile calm of adoption papers, new relatives, new expectations, and a new version of herself she was forced to build from scratch.

Losing your entire family to flames changes the way you see the world. It teaches you that everything—identity, routine, safety—can vanish without warning. And maybe, just maybe, it teaches you how to vanish yourself.

When police learned about the fire, they didn’t say it aloud, but they all had the same thought: Joan had a blueprint for disappearance written into her childhood. It didn’t mean she chose to walk away, but it meant the idea wasn’t alien to her. Reinvention was something she had done once and could, theoretically, do again.

And then there were the books.

Those twenty-five borrowed titles from the Lincoln Public Library became the centerpiece of every detective’s whiteboard. They weren’t random. They weren’t light reading. They were stories of escape, subterfuge, new identities. One novel centered on a boy who vanished to start life anew; another followed a woman who left her family without warning. There were nonfiction titles about women in crisis, about trauma, about reinvention.

Some called it coincidence. Others called it a study. The truth lived somewhere between the lines of those pages.

Was Joan intrigued by disappearance because of her past? Or was she preparing for something no one around her saw coming?

The contrast between her outer life and her inner world made investigators uneasy. On the surface, Joan was the definition of stability: PTA meetings, library visits, carefully written lists on the fridge, gentle routines, long walks with the children, quiet evenings with her husband when he wasn’t traveling.

But beneath those soft edges was a woman with a silent history of loss, a mind drawn to stories of escape, and a life that—despite its calm façade—might have felt smaller and smaller the longer she lived it.

Still, her friends swore she was happy. They described her as warm, soft-spoken, intelligent. Neighbor kids loved her. She was the mother who remembered birthdays, brought extra snacks, read aloud with voices that made toddlers giggle.

None of them believed she would abandon her children. Not even for a moment.

And that’s when the darker possibility resurfaced: abduction.

Lincoln police had seen break-ins before. They’d seen domestic disputes, robberies, scuffles. But nothing about Joan’s scene aligned neatly with any of those familiar patterns. There was no forced entry. No disarray. No ransacking. And no evidence of a stranger searching for valuables.

There was something else instead—the feeling of being watched.

Two days before Joan disappeared, a neighbor reported hearing the Risch’s garage door open and close twice in the afternoon. When she went to look, no one was there. The next day, around the exact time Joan vanished, she heard it again.

In 1961, people didn’t lock garage doors. They didn’t imagine someone slipping quietly inside, waiting, watching. But that detail—those unexplained sounds—crept into the official timeline like a shadow no one could shake.

Police believed someone may have used the garage as cover, slipping in when Martin was away, knowing Joan was alone with two small children. If that person was there the day before, they were testing the environment. Learning routines. Studying patterns.

Waiting for their moment.

Investigators came to believe Joan saw him. Maybe when she walked back from the Barker house. Maybe when she stepped into the driveway. Maybe when she realized someone had been inside her garage and turned to go back into the house.

What happened next depends on which detective you ask. Some believed she panicked and ran inside, trying to call for help. Others believed she confronted the intruder, was injured, and stumbled through the kitchen, leaving the blood trail behind.

Either way, the ripped-out telephone was impossible to ignore. No one casually tears a wall-mounted phone from its screws unless they’re desperate—or unless they’re interrupted violently.

The blood on the handset. The blood on the dial. The phone book opened to emergency numbers. Every detail pointed toward the same conclusion:

Joan tried to call for help, and something stopped her.

But if someone attacked her, why was there so little blood? And why did no one hear a sound?

Theories twisted around each other like vines.

Then came the sightings—the ones investigators wanted to dismiss but couldn’t entirely ignore.

Three women who knew Joan slightly reported seeing someone who looked like her walking along Route 128 the afternoon of the disappearance. The figure looked dazed. Possibly injured. One woman thought she saw blood on her legs. The location was ten miles from the Risch home, reachable only by car unless Joan had somehow walked for hours—unlikely, given the timeline.

Yet all three described the same thing: a woman who looked like she was trying to get somewhere but didn’t know how.

And then there was the taxi driver.

He wasn’t some attention-seeker. He wasn’t trying to insert himself into the story. He came forward only after seeing a newspaper photo days later. He remembered her because she behaved oddly—quiet, confused, unable to articulate where she wanted to go until she finally asked to be taken to the Boston bus terminal.

He dropped her off. She walked inside.

A cashier confirmed selling a ticket to a woman who looked like Joan. A ticket on a route that passed through Lincoln. As if she were trying to get home… or trying to retrace where she came from. Or trying to vanish even further.

Every lead contradicted the one before it. Every clue broke into pieces the moment police tried to assemble it. And Lincoln—once a town where nothing happened—became the center of a mystery that refused to behave like a typical crime.

While detectives chased sightings, they also interrogated the people closest to Joan.

Martin Risch remained cooperative but numb, baffled, insisting his wife must have suffered some kind of sudden mental break, maybe a concussion, maybe an injury from a fall, leaving her wandering without memory. It was the only explanation he could live with. The only version of events that didn’t require imagining his wife harmed or abducted.

But police weren’t satisfied. They wanted to know more about Joan’s marriage. About the pressures of raising two children largely alone. About her past. About the books. About the sudden move from Connecticut to Massachusetts just months before she disappeared.

Neighbors said the couple kept to themselves. Martin traveled. Joan often looked tired.

But none of that pointed toward foul play.

None of it pointed toward escape either.

The investigation grew stranger the deeper it went.

A milkman reported seeing a blue-and-white Chevrolet parked in the Risch driveway around noon—the same timeframe Mrs. Barker saw Joan for the final time. Another neighbor recalled a dark sedan idling with its engine running near the corner of Old Bedford Road that afternoon. A road worker reported a two-tone Ford driving unusually slow past the house weeks prior.

Too many cars. Too few connections. Too many shadows to pin down.

And then came the most chilling detail of all—something so subtle it could have been overlooked entirely.

A single spot of blood found on Joan’s underwear, which had been washed and folded neatly in the master bedroom. Fresh enough not to belong to a child. Small enough to be easily dismissed.

Detectives didn’t know what to do with it. It didn’t match the kitchen blood visually, and in 1961, precise testing wasn’t possible. But the existence of it raised questions few wanted to voice.

Questions about domestic strain.

Questions about unexpected injury.

Questions about whether the wound that left the trail downstairs began somewhere else.

Still, no evidence ever supported violence inside the marriage. No signs of past injuries. No secrets, at least none visible.

The underwear detail joined the others—a clue without definition.

Days became weeks. Weeks became months. Leads burned out. Tips faded. Blood evidence degraded. Witness memories blurred. Newspapers moved on. And the Risch home settled back into the stillness of the cul-de-sac, a house filled with silence but never peace.

Martin continued to live there for decades. He never changed the phone number. He never declared his wife dead. He never remarried. He kept her clothes. Her books. Her things waiting, untouched.

A kind of shrine to hope.

The children grew up carrying a story they inherited but never understood. Lillian remembered the “red paint.” David remembered nothing at all. Their childhood became a before-and-after split in half by a mystery that refused to age, refused to fade.

And the world gradually forgot Joan Risch—except for the investigators who kept her file at arm’s reach, reopening it every decade as new forensic science emerged, always hoping technology would reveal what 1961 could not.

But every time they looked closer, the case changed shape.

Every time they answered one question, two more formed.

Every time they believed they were close, the entire picture dissolved again.

Because Joan didn’t leave behind a clear narrative.

She left contradictions.

She left traces.

She left possibilities.

She left a life paused mid-sentence.

And the strangest possibility of all was the one investigators long resisted—the one that would turn the case from a tragedy into a ghost story.

What if Joan didn’t run?

What if she didn’t fall?

What if she didn’t die?

What if she disappeared… exactly the way she had been studying in all those books?

Part 3 will unravel that theory fully—the planned disappearance, the staged blood, the walk along Route 128, the bus terminal, the new-life hypothesis, and the reason some detectives believe Joan Risch may have lived for decades under another name.

For weeks after Joan Risch vanished, Lincoln police obsessed over the blood in the kitchen. It was the crime scene’s only anchor, the only physical mark left behind. Everyone assumed it told the story of a wounded woman stumbling around, pressing her hand against walls, struggling to stay upright.

But what if that assumption was wrong?

What if the blood wasn’t evidence of violence, but evidence of performance?

It took investigators years—a full decade—before they were willing to examine that idea carefully. Because to accept it meant accepting something far stranger than abduction, far colder than murder: it meant believing that Joan Risch may have staged the entire scene herself.

The theory began quietly, with a simple observation made by a detective reviewing old photos late at night. The blood on the wall wasn’t smeared in panic. It wasn’t the wild, chaotic pattern of a person fighting for their life. It was more controlled, more deliberate, as if someone pressed their thumb carefully and dragged it, not out of desperation, but direction.

There was the phone too. Torn from the wall, yes—but not smashed. Not shattered. Just pulled loose with enough force to look dramatic without rendering it completely broken. The phone book neatly open to the emergency numbers. The handset placed halfway into the trash can like someone wanted it to look discarded, not destroyed.

The baby’s coveralls on the floor, soaked in blood, felt theatrical once detectives looked at them again years later. The blood wasn’t spattered. It wasn’t sprayed. It was more like someone had dabbed or pressed fabric into a pool of blood—not the aftermath of a struggle, but the creation of one.

And the blood trail outside? It wasn’t chaotic. It was linear. Purposeful. Like someone walked straight to the car with intention, not in a dizzy panic.

All these details felt wrong when viewed through the lens of violence.

But viewed through the lens of staging?

They felt too right.

Yet staging a disappearance that convincing takes preparation. It takes study. It takes a kind of analytical curiosity that blends fear, intelligence, and imagination. And that’s when investigators returned to the library books.

There were so many of them—more than any housewife in Lincoln had ever checked out in such a short span. Books about missing women, assumed deaths, staged vanishings, split identities, sudden escapes. Books about wives who quietly left their families. Books about psychological breaks that rewrote lives.

Some detectives believed she was studying the psychology behind escape. Others believed she was preparing a script—a blueprint for a disappearance that skirted the line between tragedy and autonomy.

And yet, even the staging theory had its holes. Joan’s friends insisted she adored her children. She was attentive, present, affectionate. She didn’t show frustration or boredom or signs of wanting to run. Her marriage wasn’t perfect, but it wasn’t unhappy.

So if she staged this, why walk away from the children she loved more than anything?

That question stalled the theory for years. It was too painful to consider. Too cruel. Too cold.

But then came a new piece of information—something small, something buried deep in the original case files.

Two days before her disappearance, Joan had written a letter requesting transcripts from her old college. No one could explain why. Her friends didn’t know of any upcoming job applications. Her husband didn’t know of any academic plans. The timing was strange, and the request looked like the kind of administrative step a person takes when they’re preparing for a new life somewhere else.

The letter was never mailed.

But it existed.

And in the months before she vanished, Joan had begun behaving slightly differently. Small changes, barely noticeable unless you knew her well.

She took longer walks.

She spent more time at the library.

She grew quieter on some days.

She stared out windows longer than usual.

She seemed… thoughtful. Not unhappy. Just elsewhere.

And then there was the move.

The Risch family had lived in Lincoln for only seven months. Long enough for Joan to settle in. Not long enough for roots to hold her. Not long enough for her to feel tethered.

It was the perfect city for a new beginning—or the perfect bridge toward one.

Still, planning a disappearance doesn’t explain the blood. Or her daughter’s comment about “red paint,” which suggested Joan tried to hide the truth from a four-year-old. It also didn’t explain the sightings along Route 128—the woman who looked like Joan, limping, confused, possibly bleeding.

Unless that was part of it too.

Unless Joan needed witnesses to believe she was injured.

Unless she intentionally allowed herself to be seen.

Or unless she truly was injured—by accident, not by violence—and the staging theory wasn’t a performance but a desperate attempt to mask something else.

That’s when the final theory emerged, the one that still divides investigators even today: the head injury.

A head injury can cause people to behave erratically, to wander, to lose memory, to move in a daze. If Joan injured herself—perhaps falling in the kitchen, perhaps fainting, perhaps even hitting her head trying to reach the phone—that could explain the strange, staggered blood patterns. It could explain the dazed walk through the neighborhood. It could explain why she left the house without her purse, without preparation, without rationality.

It could explain everything without malice or planning.

If she wandered off in a fugue state, she could have been hit by a car, collapsed in the woods, or simply walked until she couldn’t walk anymore. Back then, Massachusetts was full of undeveloped land—forests, fields, marshes. A small body could be missed. A person could disappear into autumn leaves and never be found.

And yet… the taxi driver.

His testimony complicated everything. He wasn’t describing a confused, injured woman wandering blindly. He described a woman who walked with purpose, who got into his cab voluntarily, who asked to be taken to the bus station. That was not the behavior of someone with amnesia. That was the behavior of someone leaving.

Unless the cab driver was mistaken. Unless he saw a woman who resembled Joan but wasn’t her. Unless memory betrayed him the way memory often does in the days after a sensational news story breaks.

Lincoln residents argued for decades about those sightings. Some believed they were real. Some believed they were hallucinations created by the pressure to help. Others believed they were people seeing what they expected—what they feared.

But one particular detail kept the theory alive: the bus ticket. The cashier remembered selling it. The passenger resembled Joan. And the final destination was a route that would have allowed her to slip into anonymity easily.

But anonymity requires intention. Planning. Willingness to leave everything behind.

Would Joan do that?

Some investigators believed yes. Others believed absolutely not.

It was her children who made the theory difficult to swallow. Joan was fiercely devoted to them. Leaving without them seemed unthinkable, almost monstrous.

And then came the note—a detail almost forgotten, discovered decades later when the case was re-examined by a fresh set of detectives.

A friend from Connecticut had received a letter from Joan months before her disappearance. In it, Joan wrote vaguely about feeling overwhelmed. About missing city life. About feeling she wasn’t using her mind the way she once did. About wanting “something more,” although she never said what that “more” was.

It wasn’t damning. It wasn’t a confession.

But it was something.

Something that suggested she didn’t feel entirely fulfilled.

Something that hinted at a woman caught between the life she built and the life she imagined.

When the friend was re-interviewed decades later, she said something that hit investigators like a match dropped in a dry forest.

“She was always strong,” the friend said. “Stronger than people realized. And she knew how to survive anything. She already had.”

The fire.

The adoption.

The reinvention.

The books.

The quiet longing.

It painted a picture of a woman capable of disappearing—not out of cruelty, not out of fear—but out of a deep, unspoken desire to reclaim something she lost long before Lincoln, long before motherhood, long before marriage.

But if Joan staged her disappearance, she planned it with extraordinary precision and left no trace because she didn’t want to be found.

This theory gained momentum in the early 2000s, when genealogical searches became more common. Investigators quietly began scanning death records, marriage licenses, employment databases, and census reports for anyone who matched Joan’s age, appearance, educational background, or maiden name.

Nothing.

Not one possible match across the entire United States.

It was as if the earth swallowed her.

Which brought investigators back to the darkest possibility—the one they had studied from the first moment they saw blood in the kitchen.

The possibility that Joan never planned anything. That she was taken against her will. That someone used the seclusion of the neighborhood, the privacy of the home, the absence of her husband, and the vulnerability of a quiet October afternoon to strike.

The suspicious cars.

The unexplained garage door.

The ripped-out phone.

The blood.

The dazed figure walking toward Route 128.

The taxi.

The ticket.

The silence.

Every clue pointed toward a different truth.

And every truth dissolved when held up to the next clue.

There was no single theory that fit all the evidence.

Not perfectly.

Not even well.

And yet, the chilling possibility that made some investigators lose sleep wasn’t murder, or staging, or mental break.

It was this:

What if all three theories were true in fragments?

What if Joan was injured by someone—or something—inside the home?

What if she ran in fear, dazed, bleeding, trying to get help?

What if she boarded that bus in a confused state, not knowing who she was, not knowing where she was going?

What if she walked into a new life unintentionally, a ghost haunting her own future without memory of her past?

A disappearance without a plan.

An escape without intention.

A survival without identity.

The case files describe Joan’s last known movements as if they belonged to three different women.

The woman who staged blood.

The woman who fled an intruder.

The woman who walked into Boston alone.

But they were all Joan.

Or none of them.

Or one of them at the wrong time.

In the end, the most unsettling truth of the Risch case is this:

The world doesn’t always give us clean endings.

Some stories fade out instead of concluding.

Some final moments are never recovered.

Some people step out of their lives and leave a shape behind instead of an answer.

Joan Risch left behind a kitchen full of clues, a road full of sightings, a husband full of hope, and children full of questions.

She walked out of her home on October 24th, 1961.

And the world simply never saw her again.

Sixty years after Joan Risch walked out of her Lincoln, Massachusetts home and dissolved into history, her case is no longer an investigation—it’s a myth, a legend whispered by detectives who never even worked it, a story told in quiet tones inside law enforcement circles because it sits at the razor edge between logic and the inexplicable.

Most cold cases fade. Most files yellow. Most mysteries settle into dust.

But not this one.

This one stayed alive.

Not because the evidence was good. Not because leads emerged. But because nothing about the disappearance of Joan Risch behaved like a normal crime, and that irritates investigators in a way they never forget.

Cold case detectives in Middlesex County still reopen the file every decade. Not out of duty. Out of obsession. Something in the Risch case refuses to die, refuses to close, refuses to let logic win.

And with each attempt to solve it, a new layer of truth—and contradiction—emerges.

The first group to examine the case with modern tools was the Early 2000s Cold Case Initiative. They didn’t have the luxury of fresh evidence; what they had were brittle photos, faded reports, and the memory of a community that had turned over entirely. But they did have something the 1961 detectives didn’t: decades of criminal psychology and geographic profiling.

Their first conclusion shocked the living investigators who remembered the case.

They determined the blood patterns inside the Risch house were unlikely the result of an attack.

The pattern was too controlled. Too deliberate. Too directional. There were no cast-off arcs, no spatter that suggested a weapon, no signs of panic in the movement.

One analyst said the blood looked placed, not spilled.

Another said it looked “curated.”

A third said something even colder:

“It looks like she wanted us to see it.”

But they weren’t saying Joan staged everything. They were only saying the physical evidence didn’t match violence as they understood it.

For a brief moment, the staging theory roared back to life.

Then, just as quickly, it fell apart again.

Because the next forensic observation—a tiny, easily missed detail—immediately contradicted it.

A re-analysis of crime scene photos revealed faint impressions in the dust near the kitchen doorway. Impressions the original investigators believed were from movement during the struggle.

But the new analysts believed they were from shoeprints.

Two sets.

Two different sizes.

One pair matched Joan’s approximate foot size.

The other pair?

Larger.

Heavier.

Aligned with the drag marks on the floor.

Suddenly the staging theory fractured. If Joan staged the blood herself, whose shoes were those? And if someone else was inside the house, why weren’t there any footprints in the blood?

Unless they were careful.

Unless they stepped around it.

Unless they knew exactly how to avoid leaving a trail.

The second theory revived—the intruder.

Cold case detectives began building a psychological profile from scratch. Not a 1961 profile. A modern one. And the profile that emerged was not a drifter. Not a stranger passing through. Not a random predator.

It was someone local.

Someone who had observed Joan methodically.

Someone who knew when Martin traveled.

Someone who watched the house and understood the quiet rhythms of the day.

Someone who was patient.

Someone who believed he had time.

This theory gained frightening weight when detectives dug deeper into the neighbor’s account of hearing the garage door open and close without explanation. New analysts noted something: the garage was one of the few entry points not visible from the street.

If someone wanted to enter the house without being seen, that was the way.

The garage detail, dismissed in 1961 as a quirky coincidence, suddenly became a red warning light.

The cold case team traced every registered vehicle that matched the description of the strange sedan seen backing out of the driveway that afternoon. Most owners were eliminated easily. But one name remained—a man who lived less than half a mile from the Risch home.

He had died decades earlier.

He had no criminal record.

But he’d once delivered goods in the neighborhood and had reason to approach homes without suspicion.

But when investigators tracked down his surviving relatives, they discovered something unsettling: the man had been known for unpredictable moods. Sudden anger. Long absences from work. A reputation as someone who “didn’t get along with women.”

He was never charged with anything. Never suspected in any crime.

But the pieces fit in a way that made detectives uneasy.

Still, without physical evidence, without DNA, without confession, the man remained a ghost—just another shadow in a case built out of shadows.

The third theory—the head injury—was next to be re-evaluated.

Modern neurologists brought in to consult believed the possibility was stronger than anyone realized. The blood patterns could match someone experiencing a concussion or subdural bleed. They noted that individuals with certain types of head trauma can appear calm, rational, even deliberate while internally disoriented.

One neurologist described it this way:

“People imagine head trauma means chaos or collapse. In reality, a concussed person can behave with eerie calm, walking in straight lines, fixing objects, even making decisions—just not coherent ones.”

This meant Joan could have walked out on her own.

And she could have boarded a bus in a confused state.

And she could have wandered off somewhere and succumbed to the cold or her injury.

That theory explained more clues than the others.

Except one.

Why wasn’t Joan found?

Even in 1961, search parties were massive. Police combed forests, marshes, and miles of roadside. Helicopters were brought in. Dogs scoured fields. For weeks, Lincoln was transformed into a grid of boots and flashlights.

If Joan had collapsed nearby, she should have been found.

Unless she was farther.

Unless she got on that bus.

Unless memory carried her somewhere else entirely—another city, another state.

A concussed woman could travel hundreds of miles before anyone realized she was lost.

Social workers in Boston were interviewed years later and asked if they remembered an unidentified woman appearing in 1961, disoriented or injured. Some said yes, there were cases that sounded close—but no records survived. None matched conclusively.

Every theory explained something.

Every theory collapsed under something else.

It was around 2010 when a new investigative lens emerged—the behavioral one, the kind used today in complex missing-persons cases where the line between voluntary disappearance and foul play is thin.

Behavioral analysts studied Joan’s routines, emotional state, marriage, habits, and the psychological residue of childhood trauma. They studied the books. The moves. The letter for transcripts. The long walks. The heavy expectations on a woman isolated in a quiet suburban town.

And they reached a conclusion that was controversial, even among themselves:

Joan did not plan her disappearance.

But she may have been preparing for something she didn’t fully understand.

This theory, the “subconscious exit” hypothesis, suggested that Joan was in a fragile psychological state—not depressed, not suicidal, but suspended between identities. A woman who survived childhood catastrophe and rebuilt her life once might have carried a latent ability to detach when overwhelmed.

She may not have intended to run.

She may not have intended to leave.

But she may have been vulnerable to a psychological break triggered by injury, fear, or sudden stress.

In this theory, the intruder possibility and head-injury possibility merge.

Joan encounters danger—or thinks she does.

She becomes injured or panicked.

The childhood trauma reflex activates.

She walks away instead of seeking help.

She boards a bus.

She vanishes not out of desire, but out of instinct.

It was the only theory that seemed large enough to contain all the contradictions.

Not a woman running away.

Not a woman murdered.

Not a woman staging a hoax.

But a woman whose final hours were the collision of every force that ever shaped her: fear, intelligence, trauma, motherhood, survival.

Even this theory left detectives cold.

Because it didn’t give them a body.

It didn’t give them a confession.

It didn’t give them closure.

And closure, for some, became an obsession.

In 2013, a retired investigator working independently made a pilgrimage to the Risch home—now owned by a different family. He walked the driveway. He stood in the kitchen doorway. He traced the path of blood long gone. He looked through the window toward the yard.

And he said something that became famous among cold case circles:

“This is not the kind of house someone disappears from without help.”

He meant it literally. The house was too secluded. Too quiet. Too easy for someone to approach unnoticed.

But he also meant something else—something deeper.

He meant that Joan’s disappearance did not feel like the act of one person.

It felt like the collision of circumstances.

A moment too strange to repeat.

A moment that swallowed her whole.

Today, experts who study the case fall into three camps.

Those who believe an intruder took her.

Those who believe she left in a fugue state.

Those who believe she staged it intentionally.

And then there are the few—very few—who believe all theories are wrong, and that Joan’s disappearance belongs to the rarest category of all.

A “black swan disappearance.”

A vanishing shaped by chance, not motive.

A moment where a dozen small, unrelated factors aligned into one impossible outcome.

A woman with a childhood trauma history.

A woman home alone.

A woman who may have bled.

A woman who may have panicked.

A woman who may have run.

A woman who may have been seen.

A woman who may have taken a bus.

A woman who may have collapsed somewhere far away.

A woman who may have survived and reinvented herself.

A woman who may have died that same afternoon.

A woman who may have done everything or nothing.

There is no neat ending.

There is only the shape she left behind—an unfinished outline drawn in blood, memory, and speculation.

Joan Risch stepped out of a kitchen in Lincoln, Massachusetts in 1961.

And stepped into a place that exists only between pages and whispers.