Heat trembled off the blacktop like a mirage, and the red-blue strobe from a Texas DPS cruiser smeared across the silver skin of a sedan idling on the shoulder of Highway 290 by FM 1098, Prairie View, USA. The mic on a trooper’s uniform hissed, catching gravel under his boots, the rustle of summer grass, and a voice clipped, official, unmistakable: “I will light you up.” In that instant—under a noon-hammer sun that made road paint glow and the vinyl steering wheel bite—two lives and a national conversation tilted. What began as a minor traffic stop outside Prairie View A&M University in Waller County, Texas would, within days, spill from a narrow lane of asphalt to church steps in Houston, sidewalks in Chicago and New York, and candlelit lawns on campuses from Los Angeles to Brooklyn.

Sandra Bland had fire in her voice long before the dashcam ever knew her name. Born February 7, 1987, in Naperville, Illinois, she grew up one of five sisters in a house where Sunday dinners anchored the week and gospel music braided the air with brass and joy. She could debate the headlines over mashed potatoes, push back on a bad policy, quote scripture with a smile, then ask you—kindly but firmly—to do better. She filmed straight-to-phone dispatches she called “Sandy Speaks,” where her cadence mixed classroom clarity with front-porch urgency. “Being a Black person in America is very, very hard,” she said in one video, not to shock, but to state a measurable reality, then pivoted to the predicate: all voices deserve dignity. She loved students, and the campus at Prairie View—her alma mater—was supposed to be a return, a re-rooting: a new job, new apartment, new purpose. She had barely crossed the Welcome to Waller County sign when the lights rose behind her.

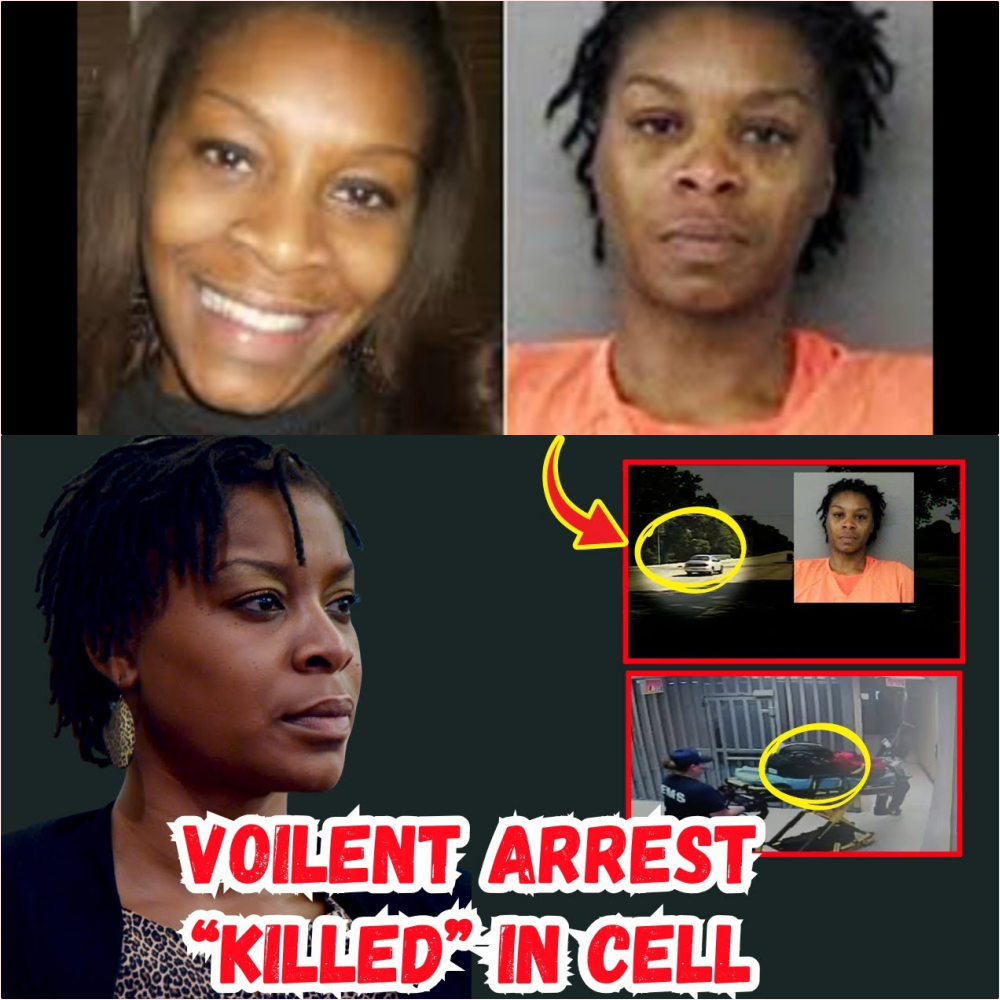

He asked for license and insurance. She complied. Sun bleached the edges of everything. The trooper stepped back to his cruiser, the silhouette of his campaign hat cutting a black coin against the Texas glare. When he returned with a citation, the air changed temperature. “Would you mind putting out your cigarette?” His tone lowered, then hardened. “Step out of the car.” She asked why. He answered with command. What followed—captured by the Texas Department of Public Safety dashcam and a bystander’s phone—was a rapid climb few could watch without feeling their own pulse rise: a door tugged open, a threat of a Taser, the sentence that would be replayed on nightly news: “I will light you up.” Moments later, a woman who had signaled a lane change to let a cruiser pass was face-down in summer grass, voice shaking but unbroken, saying she would take this to court.

By 3:37 p.m., the sedan was empty and Sandra Bland was in custody, booked on an assault on a public servant charge—a felony in Texas—and delivered to Waller County Jail a short drive away. Property bagged, laces removed, bright jumpsuit issued, she was placed in a small cell with a steel bed and a partition. According to logs, she made calls. She told her mother she’d be out Monday when bond could be arranged. She talked about a headache, about court, about fighting the charge. She sounded like a teacher reviewing a lesson plan she planned to win. The weekend stretched, and the jail—older, understaffed, with cameras that flickered and logs that later drew questions—carried on with its routine.

On the morning of July 13, 2015, just after 9 a.m., jailers reported finding her unresponsive, a plastic trash liner tied to a partition, the knot described in an official report. The Harris County medical examiner ruled suicide. The statement landed like a stone in still water and sent rings out in every direction. Her family did not accept it. Friends did not accept it. Strangers who had watched the roadside video and felt their own ribs tighten did not accept it. “My baby didn’t kill herself,” her mother said into microphones outside the Waller County building whose brick would soon be covered with posterboard and sunflowers.

Grief moved swiftly, but so did questions. Why three days in custody after a stop that started as a signal violation? Why no immediate medical evaluation after she said her head was slammed to the ground? Why were plastic liners available in a cell when prior incidents elsewhere had taught different protocols? Why did some logs stutter across time gaps? The Texas Rangers and the FBI were called in to investigate alongside local authorities; the state reiterated its findings; an independent expert hired by the family pointed to inconsistencies they believed were material; advocates emphasized a pattern—Black motorists held on minor charges, small hinges on which larger doors of harm can swing.

By then, the roadside had already become a symbol. The dashcam from Highway 290—the leveled, bureaucratic eye of state equipment—clipped and time-stamped, ran on national broadcasts. Use-of-force trainers paused it like a courtroom exhibit: the moment a request turned to a demand, the second compliance blurred with control, the slippage between ask and order that can warp any interaction. Veteran officers watched and said the word that matters most in pretext stops—de-escalation—was absent when it was needed. The trooper, Brian Encinia, was placed on administrative leave, then indicted for perjury in January 2016 based on discrepancies between his report and the video. His law enforcement career ended; the misdemeanor case was eventually dismissed in exchange for him not seeking another badge. For some, it was something; for many, it was not enough.

The civil suit that followed—filed by Sandra’s mother, Geneva Reed-Veal—moved along a slower, more technical river: depositions, duty-of-care arguments, audits of training, logs, and rounds. Lawyers asked about head-checks and ligature risks, about mental-health screenings at booking, about staffing ratios on weekends in small county facilities. In late 2016, a $1.9 million settlement resolved the wrongful death claims against Waller County and the Texas Department of Public Safety, with policy reforms attached: stricter observation protocols, improved training, better mental-health triage, and electronic monitoring designed to close the gaps where human error loves to hide. “This isn’t justice,” Geneva said. “It’s accountability.” Justice, for her, would have been a different Monday.

In 2017, the Texas Legislature passed the Sandra Bland Act, an imperfect, hard-won package. It required more robust mental-health and de-escalation training for officers, independent investigation of in-custody deaths, and stronger jail standards. Advocates noted what had been left on the cutting-room floor: a tight curb on arrests for fine-only offenses and an explicit ban on certain pretext stop practices many believed opened the door to the kind of escalation seen on the video. Even so, the bill’s name turned three syllables—San-dra-Bland—into statute, a signal that a life and a loss had forced Texas to write something down.

But laws alone do not carry candles. People do. On the lawn at Prairie View A&M University, students gathered with votives and posterboard, a mural painted with Sandra’s smile under the prairie dusk. In Chicago, a choir braided her name into verses of “This Little Light of Mine.” In New York and Los Angeles, marchers lifted her face, collaging it beside Breonna Taylor, Rekia Boyd, and Atatiana Jefferson, folding her into #SayHerName, a movement built to correct an erasure: that too often, when police violence is debated, Black women’s stories are a footnote. A generation who had first known her as a thumbnail on a phone screen, a voice in a square labeled “Sandy Speaks,” now spoke back in her cadence: respectful, insistent, urgent.

Geneva became a road warrior. Church basements, campus auditoriums, statehouse steps—she carried her daughter in a framed photo and told rooms full of people that grief has two wires, sorrow and duty, and you learn to braid them if you want to keep walking. She read aloud a letter Sandra wrote in college: “Mom, one day people are going to know my name for something good.” She let the room sit with the sentence, then finished it herself: “They do. But the cost was too high.”

In classrooms far from Waller County, future public defenders and prosecutors scrubbed through the dashcam like forensic editors. Professors paired the stop with jurisprudence: Terry v. Ohio on reasonable suspicion, Whren v. United States on pretext, the limits and obligations of “lawful orders.” They argued about compliance, contempt of cop, and the wide discretion the law grants—and the wider responsibility that discretion demands. In police academies, instructors began building scenario drills that start small and aim to stay small—because the first duty of every stop is to ensure everyone goes home.

Meanwhile, a more private curriculum unfolded in a house in Illinois and on a hill in Texas. Geneva learned how to walk into a cemetery with sunflowers, because they were Sandra’s favorite, and to kneel long enough for the grass to press a pattern into her skin. She learned how to answer a question that never stops arriving: What happened? She learned to say the facts without letting them erase the person. Sandra liked Erykah Badu and tacos, and she once argued a cousin into voting, and she had a laugh big enough to make a room look up. She wanted to mentor students at Prairie View who felt invisible, and she collected little quotes in the notes app on her phone, and she believed in hard conversations that end with someone still feeling seen.

When the country convulsed again in 2020, millions in the streets following the murder of George Floyd, Sandra’s face returned to walls in Minneapolis—a halo of yellow and blue, the words “Sandy Still Speaks” curling like a ribbon. Teens who were in middle school when the dashcam aired stitched her voice to TikTok clips of marches: “All we want is to be treated equal. Is that too much to ask?” The sound carried. The names multiplied. The list grew longer than any chant could hold, yet crowds tried, because saying the names is a way to refuse erasure, to draft a roll call the country still owes.

Waller County painted its jail. New cameras went up. Policies thickened into binders. The parking lot lines were repainted, white on black, as if tidiness could rewrite history. Some of the same staff still reported for duty under fluorescent light, punched the clock, filled out forms. The building looked newer. The story did not. In small counties across the United States, sheriffs pored over their own intake procedures, tightened checks, removed ligature risks, changed the color and material of trash liners, installed knock-and-announce sensors that force rounds to be time-stamped. Policy moved in the way it often does after grief: imperfectly, unevenly, but forward.

And still, questions live with answers in the same room. The medical examiner’s conclusion sits in a file with a signature. The family’s belief sits in a heart with a vow. Advocates keep two ledgers: one for reforms passed, one for reforms promised. Lawyers who cite the case in briefs do so with layered language—according to, the dashcam shows, the report states, the family contends—because careful words are a kind of respect, and because care is the only way to carry a story that keeps cutting.

If you stand on the shoulder of Highway 290 on a July afternoon, the sun still throws heat that makes the air look liquid, and the grasses along FM 1098 still lean as if listening. You can trace the geometry of a stop line with your toe, see the shimmer of a cruiser in your peripheral vision, and imagine the mic catching sound it will later translate into evidence. You can picture a woman in a driver’s seat, a teacher and a daughter, a voice that had already chosen to speak before anyone asked her to. You can imagine her deciding, right then, to insist on the small dignity of the moment the way she insisted on the big dignity of a life.

This is the spine that will not bend: a traffic stop in Prairie View, Texas; an arrest that escalated faster than the facts required; a weekend behind a steel door at Waller County Jail; a death the state called suicide and a family called unthinkable; an indictment for perjury that ended a trooper’s career; a settlement that bought reforms but not relief; a statute named for the woman who should have been around to read it; a country that learned a new name and found, beneath it, a set of obligations.

And this is the part that belongs to everyone who reads to the end: the ordinary work of preventing the next version of this story. It is policy and training, yes, but also posture—the willingness, at the window of a car on a county road in the United States, to keep your voice low, to let dignity sit in the passenger seat, to decide that de-escalation is not weakness but wisdom. It is a supervisor who reviews a clip and says, do it differently next time, and a city council that funds the kinds of calls social workers should answer, and a jailer who treats a routine welfare check as anything but routine. It is a mother who shows up again, and again, and again, in church basements and on capitol steps, until the bricks themselves seem to lean to listen.

If you ask Geneva what she believes now, she will not speak in legalese. She will tell you she promised her daughter to keep speaking. She will say Sandra’s name slowly, like a verse she refuses to rush. She will straighten the photo in its frame. And when she leaves, she will check that the sunflowers don’t tilt too far in the wind. Because there is a kind of justice—quiet, stubborn—that looks like caretaking: of memory, of young activists, of the idea that the smallest hinge in American life, a blink of a turn signal on Highway 290, should never swing open into a tragedy the whole nation has to carry.

That day by the shoulder, the light was merciless; the mic was honest; the road was long. The camera kept time. The voice stayed steady. The law will keep arguing with itself; the communities will keep answering back; the murals will keep fading and being painted again; the candles will keep tipping wax onto paper cups; the sun will keep falling onto that strip of Texas pavement like a verdict. And somewhere between the strobe and the shade, between the statute and the mural, between the logbook and the letter a daughter once wrote her mother, the country will keep deciding what it does—and who it is—when the next set of lights rises in the rearview.

Sandra Bland. The name arrives now with its own gravity. It calls a scene into mind, then a set of reforms, then a quiet room where a mother touches stone. It is not the whole story of justice in America; it is one story the country must keep learning how to tell—carefully, completely, without turning a person into a symbol so bright it erases her edges. It ends and doesn’t end. It pauses at a line of paint on a lane in Prairie View and continues in the soft chorus from a campus lawn: Sandy still speaks.

The heat over Highway 290 shimmered like liquid glass, the air so heavy it bent the horizon. A silver sedan idled on the shoulder near FM 1098, engine ticking under the Texas sun. Behind it, a state trooper’s cruiser glowed with red and blue light—flashing pulses that painted the asphalt in alternating fire and ice. The microphone clipped to the officer’s chest hissed and caught gravel crunching beneath his boots, the distant buzz of cicadas, and his voice—measured, official, almost rehearsed: “I will light you up.”

That sentence cut through the heat like a blade. A warning, a threat, a spark. And in the stillness that followed, the story of Sandra Bland began to change—from a traffic stop in a small American town to a national reckoning that would echo through every courthouse, classroom, and protest line in the years to come.

Prairie View, Texas. A town framed by university lawns, gas stations, and long stretches of road that look empty until they’re not. Sandra had only been there one day. She was twenty-eight, newly hired at her alma mater, Prairie View A&M University, ready to start a position that blended mentorship and student outreach—her chance to shape young voices the way professors once shaped hers. She’d driven all the way from Naperville, Illinois, her car packed with clothes, books, and the kind of hope that only comes from starting over.

The morning of July 10, 2015, was her second sunrise in Texas. The air smelled of baked asphalt and diesel. She was listening to music, humming softly, her cigarette trailing smoke through the open window. The highway curved, the patrol lights appeared, and everything ordinary collapsed into what would become one of the most scrutinized police encounters in modern American history.

When the trooper approached, his voice was cool but sharp. He asked for her license and registration. Sandra complied, polite but visibly tense. “I only changed lanes to let you pass,” she said. Her tone carried the edge of someone who’d lived long enough to recognize a pattern she shouldn’t have to explain. He returned to his cruiser, typed into his report, and when he came back, something in the air had shifted.

“Would you mind putting out your cigarette?” he asked. It wasn’t quite a question.

Sandra blinked, surprised. “Why do I have to put out my cigarette when I’m in my own car?”

The microphone captured the seconds of static between them. Then his voice rose, colder now: “Step out of the car.”

“For what?” she asked.

“I’m giving you a lawful order. Step out now.”

She refused. He yanked open the door.

“What the hell is wrong with you?” she shouted, her voice both furious and frightened.

“I’m going to light you up!” he barked, the sound of the Taser crackling beneath his words.

The dashcam showed motion but no mercy—shadows colliding, a blur of arms, and Sandra’s voice breaking through the static, a scream half-pain, half-defiance: “You’re about to break my wrist!”

Minutes later, she was in handcuffs on the roadside, pinned against the grass while traffic whispered by. Onlookers stopped but didn’t step closer. The report would later call her “combative.” The video would show something else entirely: a woman demanding the dignity the law promises but too often withholds.

By 3:37 p.m., the roadside dust had settled. The silver Hyundai sat empty, driver’s door still open. Sandra Bland had been taken into custody and booked into Waller County Jail, just a few miles away. The charge: assault on a public servant, a felony in Texas. The mugshot camera clicked once—her eyes steady, jaw set—and the image would later travel the world, pinned to headlines and protest signs, haunting and unflinching.

Inside the jail, her belongings were sealed in a plastic bag. Her phone confiscated. She was given an orange jumpsuit and placed in a narrow cell with steel fixtures and a single trash liner hanging by the partition. Jail logs later claimed she made several calls—to a friend, to her mother. She said she was fine. She said she’d be out Monday. She said her head hurt from when it hit the ground. Her tone was strong, but between sentences, there were pauses—brief, telling silences where determination met exhaustion.

Outside, life in Waller County moved on. The heat stayed merciless. The news that weekend didn’t mention her name. But in that small cell—one woman, three walls, one door—the story that would ignite a movement was already burning, quietly, in the dark.

Three days later, at approximately 9:00 a.m., an officer on morning rounds claimed he found her unresponsive. The report said she had hanged herself with a trash bag tied to the partition. The official statement arrived by noon. The world heard by evening.

But even before the press release was drafted, before the county sealed its first evidence bag, the first disbelief had already begun.

Her family didn’t accept it.

Her friends didn’t accept it.

And strangers—millions of them—watching that dashcam clip didn’t either.

Because Sandra Bland was more than an arrest. She was a mirror. And what the world saw reflected back from that roadside in Prairie View, Texas, was a truth it could no longer pretend not to see.

To be continued…

The news of Sandra Bland’s death swept through Texas like wildfire under a dry wind—fast, consuming, impossible to contain. By the time the first local segment aired on Houston’s Channel 13, disbelief had already crossed state lines. On social media, the clip from the dashcam—her calm voice turning to panic, his command cutting through—played in loops that no one could stop watching. The hashtags began: #SandraBland. #SayHerName. #WhatHappenedToSandraBland.

At first, the Waller County Sheriff’s Office issued a short statement, a few sentences wrapped in official caution: Inmate found deceased in her cell. Apparent self-inflicted hanging. Investigation ongoing. But the words felt too neat, too sanitized. People read them and felt something under the surface—the pulse of a truth being pushed down.

Her mother, Geneva Reed-Veal, was in Chicago when she got the call. She thought at first it was a mistake, a clerical error, something that could be fixed with one more phone call. Sandra had told her she’d be released Monday, had promised to call as soon as she was out. Geneva had been planning what to cook for her daughter’s welcome home dinner—fried catfish, Sandra’s favorite.

But then came the confirmation. And the world collapsed into the sound of her mother’s scream.

The following morning, reporters stood outside Waller County Jail, microphones like bayonets aimed at the brick facade. “Officials say there’s no sign of foul play,” one correspondent repeated live on CNN, while behind her, protestors were already gathering—homemade signs raised in the searing Texas heat. “My baby didn’t kill herself,” Geneva said through tears. Her voice cracked, but the sentence never broke.

In Prairie View, students who had only met Sandra once, or had only heard of her through her old YouTube channel, lit candles along the campus lawn. They painted her initials—S.B.—on cardboard, on walls, on hearts. The local community church opened its doors for an impromptu vigil, the pews filled with strangers who had never met her but somehow felt like they had.

It wasn’t just grief. It was confusion laced with fury. How does a routine traffic stop end in death? How does a young woman with a new job, a family waiting, and a future laid out simply vanish into a report that called her “non-responsive”?

In Chicago, her sisters stood before cameras in matching black shirts that read Sandy Speaks. Their faces were a blend of rage and determination. “If you knew my sister,” one said, “you’d know she was a fighter. She wasn’t someone who gave up. She didn’t take her own life—something happened to her.”

By that evening, her name had entered living rooms across the United States. In New York, Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Dallas, protests formed like aftershocks. People carried candles and smartphones, chanting, “What happened to Sandra Bland?” as though asking the question loudly enough might bring an answer.

The following week, Waller County officials released the dashcam footage in an attempt to calm the outrage. Instead, it did the opposite. The video began with sunlight flashing off the silver hood of Sandra’s car, the trooper’s boots crunching gravel, and that now-infamous exchange. What caught the public’s attention, though, wasn’t just the argument—it was the tone, the imbalance.

Viewers noticed how quickly the conversation spiraled from civility to confrontation. They watched as she questioned his authority—“Why am I being arrested?”—and saw him move closer, hand hovering near his Taser. They heard him say it again: “I will light you up.”

The clip went viral. Cable anchors debated it, activists analyzed it frame by frame. Was it about ego? Race? Gender? Power? The answer, it seemed, was all of it. The image of Sandra Bland became both tragedy and symbol—the crossroads of systemic fault lines too long ignored.

When journalists asked for surveillance footage from the jail, officials hesitated. When they finally released it, critics noticed gaps—missing minutes, flickers in the recording. Online, theories multiplied. Some said it was negligence; others whispered of a cover-up.

The Texas Rangers and the FBI were called in. The county courthouse filled with tension. Reporters camped outside for days. Each press conference felt like a standoff between grief and bureaucracy. The sheriff’s spokesperson repeated the phrase “no evidence of foul play” so often it began to sound like a script. But for Geneva and her daughters, the words were hollow.

Every night, Geneva sat in her living room surrounded by photos of Sandra—her graduation picture from Prairie View A&M University, her wide smile, her laughter frozen in time. She watched the news play the same thirty-second clip over and over. Her daughter’s voice, firm and fearless, became a ghost that filled the house.

“I’m going to take this to court.”

That was one of the last things Sandra had said before she was silenced.

The family hired attorneys. Civil rights leaders arrived in Waller County. The NAACP, the ACLU, and the Black Lives Matter network all released statements demanding an independent investigation. The case was no longer just about one woman—it was about the machinery of American justice itself.

By mid-August, the protests had turned into organized marches. Crowds in Houston and Dallas moved through downtown streets with signs reading: “A traffic stop should not be a death sentence.” Choirs sang hymns while police helicopters hovered overhead. The mixture of pain and resolve was almost tangible—like standing inside a thunderstorm waiting for the lightning to strike.

Geneva began speaking publicly. Her grief had sharpened into something else: conviction. “They thought they could silence her,” she said at one rally, “but Sandy still speaks—through me, through all of us.”

The crowd erupted. It wasn’t a chant this time; it was a promise.

As the weeks passed, new layers of the story surfaced. Reports revealed Waller County Jail had failed several compliance checks in the years prior—issues with staffing, training, and mental health assessments. A 2012 inspection had noted inadequate monitoring of detainees at risk of self-harm. The jail had promised reforms. Few had been implemented.

For Sandra’s family, those details weren’t technical—they were personal. “If they had done their job,” Geneva told reporters, “my daughter would still be alive.”

But behind the microphones and headlines, the pain was quieter, harder to film. At night, Geneva scrolled through old texts. Love you, Mom. Call you soon. The words glowed in her hands like tiny embers. In another message, Sandra had written, ‘I’m ready to change the world, Mom.’

And maybe she had. Just not in the way she intended.

The name Sandra Bland was no longer confined to a case file. It had become a rallying cry—a demand, a mirror, a warning. Her death forced America to confront the smallest question with the largest weight: What happens when a system meant to protect ends up destroying the very people it swore to serve?

Under the fierce Texas sun, the flowers left at the gates of Waller County Jail began to wilt. But every night, more appeared. Roses, lilies, candles. Notes written in careful handwriting: We see you, Sandy. We speak your name. We will not forget.

And in those quiet offerings, beneath the weight of grief and injustice, something enduring began to grow. Not closure. Not peace. But resolve—a promise whispered by thousands of strangers who had never met her, standing shoulder to shoulder across America.

To be continued…

By late August, the Texas summer had turned brutal. The air in Waller County hung thick with humidity and tension—the kind of air that felt like it remembered. Outside the county jail, flowers browned and curled beneath the sun, yet people kept coming. Some brought candles. Others brought bullhorns. All brought questions.

“What happened to Sandra Bland?” the crowd chanted, again and again, as if repetition could force an answer from brick and silence. But the building gave nothing back. The local sheriff’s office tried to speak in statements—controlled, distant, measured words about “procedures” and “protocols”—but those words dissolved the moment they met the heat of public outrage.

Across the United States, Sandra’s name had begun to echo in places far from Prairie View. Chicago, her hometown, became a center of grief and determination. At a vigil outside her old high school, former teachers and classmates gathered, holding signs painted in bright strokes: “Sandy Speaks—Still.” Inside classrooms where Sandra once debated politics and social justice, students now studied her story as living history.

But Geneva Reed-Veal, her mother, couldn’t rest. Each day felt like waking inside a storm that wouldn’t end. She attended meetings with lawyers, reviewed autopsy reports that used words like “asphyxiation” and “ligature marks,” words so clinical they stripped away everything human. But Geneva read every line anyway, whispering under her breath: “No. That’s not my daughter.”

The Texas Rangers and FBI investigation began in earnest. Evidence from the jail was cataloged: photographs of the cell, the plastic trash liner tied to the metal partition, time logs of cell checks that looked suspiciously incomplete. The state promised transparency, but transparency in cases like these rarely feels like light—it feels like smoke, thin and choking.

At a press conference, the county’s district attorney stood before flashing cameras. “We have found no evidence of foul play,” he said. The microphones caught Geneva’s sharp inhale from the front row. Her hand trembled as she held a framed photo of Sandra—the one from her Prairie View A&M graduation, cap tilted slightly to the side, smile wide and certain.

Reporters turned to her afterward, microphones thrust forward like weapons.

“Mrs. Reed-Veal, do you believe your daughter took her own life?”

Geneva’s voice was low but unwavering. “My daughter wasn’t suicidal. She was excited. She was ready for her new job. She was planning her future. Don’t you dare tell me she gave up.”

Her words hit the evening news, her tone raw and unfiltered, reverberating across the country. For the first time, many Americans looked past the headlines and saw the person—the woman who had laughed loudly, who had danced with her sisters in their kitchen, who had posted videos to inspire young Black women to stand tall. Sandra Bland was no longer a name on a police report. She was a face, a life, and a mirror reflecting a deeper American wound.

As the days passed, the hashtag #SayHerName began to surge again online. It had first been coined months earlier to highlight the stories of Black women lost to police violence—stories too often buried beneath louder headlines. Now, Sandra’s death reignited it, giving it new urgency, new fire.

In Los Angeles, hundreds gathered outside city hall, chanting Sandra’s name under banners that read “Justice for Sandy.” In New York City, protesters filled Union Square, their signs illuminated by phone screens in the night. And in Atlanta, church bells rang twelve times, one for each hour Sandra had been alone in her cell before guards claimed to find her.

The outrage grew because her story felt painfully familiar. Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Michael Brown—names already carved into America’s uneasy conscience—now had a sister among them. Each case different in its details, yet hauntingly identical in pattern: a minor infraction, an encounter that escalates, a Black body detained, then gone.

Civil rights attorney Cannon Lambert, representing Sandra’s family, stood before the cameras in mid-September. “If Sandra Bland were white,” he said flatly, “she would be alive today.” The words landed like a gavel, undeniable and sharp.

The family filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Waller County and the Texas Department of Public Safety, alleging negligence, misconduct, and failure to ensure her safety in custody. The case made headlines across major outlets—The New York Times, The Washington Post, CNN, NBC, all dissecting every line of the suit.

While the courts prepared for their slow grind toward justice, Geneva found herself thrust into a different role: activist, spokeswoman, reluctant leader. Invitations poured in—from churches, universities, advocacy groups. She spoke wherever she could, sometimes to thousands, sometimes to a dozen. Her message never changed: “They silenced my daughter’s voice, so I’m going to make sure mine is loud enough for both of us.”

In one speech at a rally in Houston, Geneva stood beneath the Texas sky, microphone trembling in her hand. “Sandra told the world to speak up,” she said, her voice cracking but fierce. “She said we have to stop accepting things that are not right. So we’re going to keep saying her name until the people in power remember that she was not a number, not a statistic—she was a human being.”

The crowd roared, their voices merging into one—“SANDRA BLAND! SANDRA BLAND!” The chant rolled across the street like thunder.

Meanwhile, pressure mounted on Texas state trooper Brian Encinia, the man who had pulled her over. As public outrage grew, every second of the dashcam footage was examined by legal experts and journalists. Forensic video analysts slowed down frames to the millisecond, mapping the shift in tone, the moment when professionalism became provocation.

In January 2016, a grand jury indicted Encinia for perjury—a charge based on his claim that he removed Sandra from her car “for her safety.” The video showed otherwise. The indictment was minor compared to the scale of the tragedy, but for many, it was proof that at least one piece of the system had acknowledged the lie.

Encinia was fired from the Texas Department of Public Safety shortly after. Yet no one was charged in connection to Sandra’s death itself. The perjury indictment felt like a bandage on a deep wound—symbolic, insufficient, but something.

Geneva attended every hearing, dressed in black, sitting stone-still in the gallery. Reporters noticed how she never cried during the proceedings. When asked why, she said, “Because they’d like that too much. My tears don’t belong to them.”

But away from cameras, in the quiet hours of night, she did cry. Sometimes she spoke aloud to her daughter, as though Sandra were sitting beside her again. “You were supposed to change the world,” she’d whisper. “And you did, baby. You did.”

By the summer of 2016, the Sandra Bland case had become more than a legal battle—it had become a national symbol of systemic failure. Activists pushed for legislative reform, and in 2017, the Sandra Bland Act was passed in Texas. The bill mandated de-escalation training for officers, improved mental health resources in jails, and required independent investigation of jail deaths.

The law was progress, but Geneva called it “a half-measure.” It didn’t address racial profiling, or the discretion officers had in traffic stops—the very thing that had started this nightmare. “They fixed the aftermath,” she told a crowd at Prairie View A&M, “but not the cause.”

Still, the act bore her daughter’s name. Three words engraved in state law. Sandra Bland. A name that once belonged to one woman now belonged to a movement.

That same year, murals began appearing across cities. In Houston, a wall painted with Sandra’s face, eyes lifted toward the sky, the words “Sandy Still Speaks” swirling in blue beneath. In Brooklyn, a portrait of her smiling—a halo of sunflowers framing her head. In Chicago, students at her alma mater created a memorial garden.

Her story had become both grief and gospel—spoken at rallies, whispered in classrooms, tattooed on skin. It carried pain, yes, but also something else: a demand that no more names be added to the list.

Geneva continued to travel, her voice steadying over time. At one event, a journalist asked if she ever grew tired of telling the story. She looked up, eyes shining but unflinching. “Tired?” she said. “I’ll rest when the world stops giving mothers stories like mine to tell.”

In that moment, the crowd stood in silence. It wasn’t applause that followed—it was reverence. Because everyone there knew that beneath the speeches and the signs and the slogans, this was what the story had always been about: a mother, a daughter, and the brutal, beautiful act of refusing to be silent.

And though Sandra’s voice had been taken from her, her message had not. Across America, it still moved—through microphones, through murals, through every person who dared to ask out loud the question that started it all:

What happened to Sandra Bland?

The years after Sandra Bland’s death unfolded like chapters in a book that refused to close. Every time people thought the story had settled, it opened again—new headlines, new footage, new voices demanding that her name not be forgotten. Sandra Bland was no longer just a name; she was a symbol, a wound, and a mirror that forced America to confront itself.

In Prairie View, Texas, the road where she was pulled over—FM 1098—was quiet again. Cars passed the spot where her silver Hyundai once stopped under the July sun, unaware of how much history that patch of asphalt carried. But for those who knew, the place felt haunted. There was something about the way the light hit the road in the afternoons, how the air went still, as if it remembered.

Each summer, around the anniversary of her death, people came back. Students, activists, strangers who had only known her through a screen. They laid flowers, tied ribbons, left handwritten notes that the wind sometimes carried across the fields. We see you, Sandy. We still speak.

Back in Illinois, Geneva Reed-Veal had transformed her grief into a relentless mission. She spoke at universities, church halls, courtrooms—anywhere someone would listen. Her voice carried both steel and sorrow. “They thought she was just one more,” she’d say, pausing to let the silence hang, “but my daughter was the match that lit a fire they can’t put out.”

Everywhere Geneva went, someone would approach her quietly afterward—another mother, another sister, another woman holding a folded photo of someone gone too soon. They didn’t need to explain. Geneva would hug them, whisper, “I know.”

The Sandra Bland Act, passed in 2017, was supposed to be the system’s apology written in law. It promised reforms—mental health checks, de-escalation training, better jail oversight. On paper, it was progress. But Geneva called it “a seed planted in dry soil.” The law still didn’t ban the kind of discretionary traffic stops that had started Sandra’s nightmare. “It’s not enough to care after the fact,” she said on national television. “You have to stop the storm before it begins.”

Meanwhile, across the United States, Sandra’s story continued to ripple. Artists painted her face on city walls, her eyes steady, her expression neither sad nor angry—just knowing. Poets wrote verses that began with her words from her “Sandy Speaks” videos: “Being a Black person in America is very, very hard.” Those videos, recorded in her bedroom long before the world knew her name, became sacred artifacts. Her voice—firm, witty, passionate—was replayed at rallies from New York to Los Angeles.

One night, at a protest in Washington, D.C., a group of young women held up their phones, playing clips of Sandra’s voice over the crowd. Her words echoed between the marble walls of the Capitol: “We have to stop sitting back and expecting change to come to us. We have to get up and make it happen.”

The crowd fell silent for a moment. Then they began to chant her name—“Sandra! Sandra! Sandra!”—as if calling her back to stand among them.

By then, Geneva had joined forces with a group known as The Mothers of the Movement—women whose children had died in encounters with police or through gun violence. Among them were Sybrina Fulton, mother of Trayvon Martin, and Gwen Carr, mother of Eric Garner. Together, they spoke not only of grief, but of survival.

At a conference in Houston, Geneva stood on stage beside Sybrina and Gwen. “They took our children,” she said, her voice shaking, “but they didn’t take our purpose. We are still here. And we will not stop.” The audience rose to their feet, many in tears.

In 2018, a documentary titled Say Her Name: The Life and Death of Sandra Bland premiered on HBO. Millions watched. The film peeled back the layers of her life—the daughter, the sister, the activist, the dreamer. It didn’t sensationalize her death; it illuminated her life. Viewers heard her laughter, saw her videos, read her handwritten notes. For the first time, many understood that Sandra’s story wasn’t about how she died—it was about how she lived, and how that life had been unjustly stolen.

The documentary reignited public interest in her case. Activists demanded reopening of investigations, citing inconsistencies in the official narrative. Independent forensic experts pointed again to missing surveillance footage, irregular jail logs, and the absence of psychological screening protocols that could have saved her.

But despite mounting pressure, the case remained “closed.” There was no indictment for her death, no formal accountability. Yet, the lack of closure became the movement’s fuel.

Every year, on July 13th, the anniversary of her death, vigils took place in multiple cities. In Houston, people gathered with candles at the courthouse steps. In Chicago, Sandra’s family hosted an event called The Light Continues. And in Prairie View, where she had once dreamed of mentoring students, a mural of her smiling face stood watch over the campus. Beneath it were three painted words: “Still speaking truth.”

By 2020, as the nation erupted after the killing of George Floyd, Sandra’s name reemerged, painted across banners, shouted in protests, written in chalk across courthouse steps. Her story bridged generations of outrage—proof that what had begun on a quiet Texas highway in 2015 had never really ended.

At one march in Minneapolis, a young woman held up a poster that read: “She spoke, and we finally listened.” When asked why she marched with Sandra’s face instead of a newer case, she said simply, “Because she taught us how to fight back.”

That same summer, Geneva found herself once again surrounded by microphones, this time at a rally in Austin. She wore a black shirt with her daughter’s photo across the front, her arms lifted high. “When they took Sandra,” she said, “they didn’t just take a life—they took a future. But look around you. She’s still here.”

The crowd roared, and for a moment, it felt like Sandra was there too—in the rhythm of the chants, in the fierce warmth of the Texas sun, in the collective breath of a country still wrestling with the truth.

But for Geneva, the fight never really ended. The years had worn her, but not broken her. Sometimes, in quiet moments, she’d visit Sandra’s grave in Willow Springs Cemetery, bringing fresh sunflowers—Sandra’s favorite. She’d kneel in the grass, brush dirt from the headstone, and whisper, “You did it, baby. They know your name.”

She never stayed long. There was always another call, another invitation to speak, another mother to comfort. Because Geneva understood now what her daughter had meant when she said, “Sandy Speaks.” It wasn’t about her voice alone—it was about every voice that refused to be silenced after hers.

That winter, Geneva received a letter from a college student at Prairie View. It read, “I joined the debate team because of Sandra. She made me believe I could make change. I want to be the kind of woman who makes people listen.” Geneva folded the letter, pressed it to her chest, and wept quietly—not in pain this time, but in recognition.

Sandra Bland had become more than the moment she was lost. She had become a movement woven into the nation’s conscience, an echo that still vibrated through every march, every candlelight vigil, every reform bill debated in Congress.

And in the soft light of those vigils, where strangers’ voices rose together under the Texas sky, the story always came full circle—to a young woman sitting in her car on Highway 290, sunlight on her face, conviction in her voice, and a belief that speaking truth could change the world.

She was right.

Sandra Bland still speaks.

To be continued…

The night after the fifth anniversary of Sandra Bland’s death, the air over Prairie View, Texas, was thick with summer heat and candle smoke. A thousand people stood shoulder to shoulder beneath the mural of her face — her eyes fierce, her smile defiant — the same face that had once stared directly into a camera and said, “It’s time, y’all.”

Now, five years later, her voice still lingered. The sound system hummed with her recordings — snippets of Sandy Speaks videos playing between gospel songs and speeches. The crowd listened as her laughter spilled through the speakers, that big, unguarded laugh that made strangers smile. Then came her voice again, steady and clear: “If you see injustice, and you do nothing, you’ve chosen the side of the oppressor.”

The crowd grew still. Even the wind seemed to stop moving. Somewhere in the front row, Geneva Reed-Veal, Sandra’s mother, closed her eyes. She could almost feel her daughter’s presence in the air — the warmth of her conviction, the rhythm of her words. Geneva had heard those clips hundreds of times, but each one hit like the first: pride, pain, fury, faith — all tangled into one sound that refused to fade.

When Geneva stepped onto the stage, the applause came like thunder. She didn’t raise her hands for quiet. She simply waited until the noise softened, until the crowd was breathing with her.

“My baby spoke truth,” she began. “And truth never dies. You can lock a body in a cell, but you can’t bury a voice.”

There was silence then — deep, heavy silence — as if everyone there felt the same truth pressing on their chests.

By 2020, Sandra Bland’s name had become a part of America’s pulse. Her story wasn’t an isolated tragedy anymore; it was woven into the larger fabric of a movement that had stretched across every state. From Chicago to Atlanta, from Dallas to New York, murals, documentaries, and classrooms carried her legacy.

The protests that erupted after George Floyd’s murder reignited Sandra’s story. Her face appeared again on posters beside his, beside Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Ahmaud Arbery. The same question echoed through the streets, written in paint on signs and sidewalks: “Why does this keep happening?”

But for Geneva, the noise of the crowds was never enough. Change needed to move beyond chants and hashtags — it needed to live in the laws, in the daily conduct of the officers, in the systems that failed her daughter. She worked tirelessly with community leaders and lawmakers, urging them to strengthen the Sandra Bland Act — to include clauses against racial profiling, to make sure no one else would be arrested for a minor traffic infraction that should have ended with a warning.

Her meetings were relentless. Senators, mayors, chiefs of police — some sympathetic, others defensive — all heard the same sentence from her lips: “I’m not asking for sympathy. I’m demanding accountability.”

Everywhere she went, she carried a small leather-bound notebook — its pages filled with Sandra’s quotes, handwritten notes, and personal reminders: “Speak calmly. Stand firmly. Don’t cry here.” She had learned to hold her grief like a blade — sharp, controlled, never dulled.

At one conference in Washington D.C., Geneva was invited to speak on police reform. The room was full of journalists, politicians, and activists. Behind her on the projection screen, a still photo of Sandra appeared — her face lit by sunlight, her expression serious but alive.

“People keep telling me to move on,” Geneva said into the microphone. “But tell me — how do you move on from something that’s still happening? My daughter didn’t die in vain. Her death was the moment the world stopped pretending everything was fine.”

She paused, looking out over the crowd. “You all saw the video. You saw how calm she was, how human she was, how quickly that didn’t matter. That’s what I want you to remember. Every person you profile, every person you dismiss — they have a mother who loves them just like I loved her.”

When she finished, the room rose to its feet. There were no claps at first — just tears. Then a slow, thunderous standing ovation that went on for minutes.

Afterward, a young woman approached Geneva. She was no older than Sandra had been when she died. Her voice trembled as she said, “Ms. Reed-Veal, I study criminal justice because of your daughter. I want to change how this system works.” Geneva took her hand and said, “Then you already have.”

Meanwhile, at Prairie View A&M University, students had transformed Sandra’s old activism into a mentorship program. They called it The Sandy Speaks Initiative — a leadership forum that helped young Black women find their voices through advocacy and education. Every semester, they played her videos in class, her words a living syllabus.

At one of those sessions, a freshman asked quietly, “Do you think she knew? That one day, she’d change the world?”

The room fell silent before the professor replied, “She didn’t have to know. She just had to speak. And we’re here because she did.”

Across the U.S., her name began to appear in textbooks, in law syllabi, in the speeches of civil rights leaders who invoked her as a turning point. Scholars called her death “a moral inflection” — a moment that redefined how America saw not just police brutality, but the invisibility of Black women within it.

But for Geneva, the fame meant little. It didn’t replace the empty chair at family dinners. It didn’t fill the silence when she passed Sandra’s old room, still neat, still untouched. Sometimes she’d open the door and stand there, letting the smell of old perfume and folded laundry wash over her. A framed picture sat on the dresser — Sandra at twenty-eight, standing tall in her graduation gown, eyes full of promise. Geneva would touch the frame and whisper, “You did good, baby.”

Yet even as grief lived quietly in her home, purpose lived loudly in the world outside. The #SayHerName movement gained strength across continents. In London, protesters painted Sandra’s face on the side of a building across from the U.S. embassy. In Paris, her name was projected across the walls of the Louvre during an anti-racism march. In Cape Town, South Africa, women carried banners that read, “From Texas to Africa — we hear you, Sandra.”

Her story had transcended borders. It had become part of a universal language of justice.

Five years after her death, Geneva attended the dedication of the Sandra Bland Memorial Scholarship at Prairie View A&M. The auditorium was packed — students, faculty, community members, all gathered beneath a massive portrait of Sandra. When the first recipient, a law student named Tiana Brooks, took the stage, her voice shook. “This scholarship isn’t just money,” she said. “It’s a reminder that when one woman speaks truth, generations can find their voice.”

Geneva smiled through tears. For once, the ache in her chest felt lighter. She could almost imagine Sandra standing there beside her, proud, amused, whispering, “See, Mama? I told you I was gonna change things.”

That night, after the ceremony, Geneva drove back to her hotel through the quiet Texas roads — the same stretch of highway her daughter had once driven, the same air that had carried her last words. The moon hung low, pale and full. Geneva rolled down the window and let the wind hit her face. She whispered into the night, “We’re still speaking, baby. And they’re listening now.”

In the distance, the town lights flickered like stars. The same sky Sandra once looked up at was still there, vast and unchanging. The same country, still wrestling with its conscience. The same fight, still burning bright.

And beneath it all, one voice — clear, unyielding, eternal — still echoing across America:

“Sandy Speaks.”

To be continued…

The years rolled forward, but for Geneva Reed-Veal, time never really moved on — it only deepened. Each sunrise in Texas or back home in Illinois carried the same rhythm: an ache that never left, a mission that never stopped. Sandra Bland was gone, yet she was everywhere — on murals, on protest signs, in the trembling voices of young women who refused to stay quiet.

Every July, Geneva returned to Prairie View, where Sandra had been arrested, where everything had unraveled. The roads hadn’t changed much — the sun still baked the pavement, the grass still whispered in the wind. But the silence there carried memory now. People who drove by that intersection on Highway 290 sometimes pulled over to leave flowers, stickers, or notes. One man had written on a small piece of cardboard: “You didn’t die in vain, Sandy.”

That intersection had become something sacred — not a crime scene, but a pilgrimage site. A place where pain met purpose.

Geneva always arrived early in the morning, before the crowd gathered. She’d park, step out of her car, and stand in the same spot her daughter once did. Sometimes she’d whisper, “I’m here, baby.” Sometimes she’d say nothing at all.

Then, slowly, people would begin to arrive — college students, mothers, activists, and reporters with cameras that buzzed like flies in the heat. Geneva didn’t mind them anymore. She’d learned that visibility was its own weapon. Every flash, every broadcast, every mention kept Sandra alive in the public conscience.

That year’s vigil was different. The crowd was larger, the mood heavier. The nation was still trembling after George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many others. It wasn’t just a commemoration; it was a reckoning.

The speaker lineup was full — pastors, professors, organizers, even local officials who had once stayed silent now stood at the mic, trying to find the right words. But the crowd waited for one voice — Geneva’s.

When she finally stepped forward, she didn’t speak right away. She looked at the sea of faces — people holding candles, faces streaked with sweat and tears. She took a breath that seemed to pull in all the air from the Texas fields. Then she said quietly, “Every time you say her name, you keep her alive.”

A murmur moved through the crowd.

“They thought her story would fade after a week, a month, a year,” Geneva continued. “But here we are — five years, ten years — and you’re still here. You’re still saying her name. That means they didn’t win.”

Her voice grew stronger. “My daughter was arrested for not signaling a lane change. A lane change. That’s what started all this. But let me tell you something — that signal wasn’t the one that mattered. The real signal was the one she sent to the world: that we will not bow. We will not forget. We will not stop.”

The crowd erupted, voices chanting “Sandra Bland! Sandra Bland!” The chant built like thunder — rolling, alive, unstoppable.

Later that night, when the crowd dispersed and the candles burned low, Geneva sat quietly with a few of Sandra’s old friends. One of them, a woman named Denise, had gone to college with Sandra at Prairie View. She said softly, “You know, Sandy used to talk about this exact road. She’d say, ‘One day they’re gonna know my name. Not because I want fame — because I want change.’”

Geneva smiled, tears glinting in the candlelight. “She was right. They do know her name. But God, I wish they’d known it for a different reason.”

Across the country, Sandra’s case had become a cornerstone in law schools and justice programs. Professors analyzed the dashcam footage not as a crime clip, but as a study in power, bias, and escalation. Young law students debated the ethics of policing, the failures of oversight, the systemic negligence that let her die alone in that cell. Her story had become a lens — and through it, America was forced to see itself.

In New York, activists launched the Sandra Bland Center for Justice, a nonprofit dedicated to reforming traffic-stop policies and custodial care systems. Geneva attended the opening ceremony. The building was small but bright, its walls covered in murals painted by young artists. One wall bore Sandra’s words in bold letters: “You can’t silence the truth — it’s louder than fear.”

Geneva stood in front of it for a long moment. “She’d love this,” she whispered.

Her work took her from state to state. From Austin to Washington D.C., she met lawmakers and social workers, police chiefs and parents. Every speech she gave began the same way: “My name is Geneva Reed-Veal, and I’m Sandra Bland’s mother.” And every time, the room would fall silent.

But the movement wasn’t hers alone anymore. A new generation had risen — young, sharp, unafraid. They didn’t just march; they organized, filmed, documented. They turned outrage into policy. They built platforms that carried voices like Sandra’s into the digital ether, where they couldn’t be erased.

In 2021, a viral TikTok series titled #StillSpeaking brought Sandra’s Sandy Speaks videos back into the mainstream. Millions watched as her face filled their screens — that mix of warmth and conviction, humor and rage. Her words hit harder now than ever: “At the end of the day, we are human. Treat us like it.”

Viewers commented by the thousands: “I wasn’t old enough to know her story before, but now I do.” Others wrote simply: “She still speaks.”

Meanwhile, Geneva had begun writing a memoir. Late at night, she’d sit at her kitchen table, the glow from her laptop soft against the dark. The book wasn’t just about loss; it was about awakening — her daughter’s and her own. She titled it The Fire She Left Behind.

Each chapter was a confession — raw, tender, unfiltered. She wrote about the nights she couldn’t sleep, the phone calls she still replayed in her head, the smell of Sandra’s hair oil that lingered in her old pillowcase. She wrote about the moment she first saw the viral dashcam footage, how she’d screamed until her throat gave out. And she wrote about the letters she received from strangers — teachers, students, mothers — who said Sandra had changed the way they saw justice.

When the book was finally published, it didn’t just sell. It moved. Reviews called it “a mother’s manifesto,” “a testimony of courage,” “a blueprint for how grief can spark revolution.” Geneva didn’t care about the headlines. She cared that people were still listening.

In one interview, she said, “I don’t want my daughter’s name to live because of pain. I want it to live because of purpose.”

And purpose lived on.

Prairie View A&M introduced a new social justice curriculum in Sandra’s honor. Every freshman was required to take a seminar on civic responsibility — to learn not just what the law is, but what it should be. Her story was the opening lesson.

One day, a professor played Sandra’s final Sandy Speaks video for her students. When it ended, the room was silent. Then a young man raised his hand and said, “It’s strange. She was just talking to her camera. But it feels like she was talking to all of us.”

That’s what Sandra Bland had done — she had turned an ordinary act of self-expression into prophecy.

Years later, Geneva visited a classroom herself. She stood in the back as students presented research projects inspired by Sandra’s case. One girl — no older than twenty — said, “Sandra taught me that being brave doesn’t mean being unafraid. It means speaking even when you are.”

When class ended, the girl approached Geneva. “Thank you,” she whispered. Geneva smiled softly and said, “Don’t thank me. Thank her. She’s the reason we’re still speaking.”

That night, Geneva drove home under a wide Texas sky. The stars above seemed endless — the same stars that had watched over her daughter that last night in 2015. She rolled down the window and let the warm air fill the car. Somewhere in the hum of the highway, in the rhythm of her heartbeat, she could almost hear Sandra’s laughter again.

And for the first time in years, Geneva didn’t cry. She smiled — a small, tired, powerful smile. Because she knew that as long as there were people still speaking her daughter’s name, Sandra wasn’t gone. She was still here — in the protests, in the classrooms, in the quiet prayers whispered before bed.

Her voice had become eternal.

And in the hush of the Texas night, it seemed to whisper back — fierce, fearless, and unbroken:

“Sandy speaks. Still.”