The lake throws coins of light against my ceiling—silver, spinning, reckless—while I stand barefoot on walnut floors and turn the warm house key in my palm like proof I exist. Three bedrooms. One office facing glassy water. A dock with a red kayak tied to the third post. Oregon sun in a rare generous mood. And me—Cassandra, thirty-two, Multnomah County ZIP 972—owner of all of it in the United States of America. Five years ago I was showering at a campus gym and sleeping in a Honda Civic with my textbooks hidden under the seat. Today, I can smell fresh polish on wood and espresso blooming in the kitchen, and I know a phone call is coming that will try to turn this house into a stage I never auditioned for.

If you’ve ever waited for the wrong ring—on a TriMet bus rattling over the Hawthorne, in a Starbucks line by Pioneer Courthouse Square, at a nail salon on SE Division—you’ll know the feeling: a slow storm pressing on the ribcage. My parents would ask to host my brother’s wedding here. They wouldn’t really ask. They would assume. They would arrive with 150 guests and a caterer convoy and call it “family,” and they would expect me to open my gate for the pageant. They had no idea what I’d already set in motion.

I was raised in Portland, Oregon, where drizzle powders the mornings and maple leaves paste to your shoes like unposted letters. On paper we were a holiday-card family: my father, Richard, a hospital administrator who memorized hallways and handshakes; my mother, Martha, a real-estate agent who could sell a house she couldn’t afford by finding its best light at 4:17 p.m. We had a golden retriever who tilted his head on cue and a staircase perfect for ribboned garland. The photos were tight smiles and knitted sweaters. The sound beneath—the faint starting buzz of favoritism—was a small spoon on a crystal rim, easy to miss.

Adam arrived when I was three. At first it was a bigger bow on his birthday, an extra layer of cheesecake on his plate. Then the pattern hardened like cooling caramel. I brought home a sixth-grade report card with straight A’s; Mom said “good job” the way you sneeze—automatic, barely present—and slid the paper under a stack of PGE bills. That evening Adam dumped C’s and a lone B- on the table. Dad took us to ice cream to “celebrate improvement.” At sixteen I learned bus schedules to get to my part-time job. Adam got a Ford Mustang because he “needed reliable transportation for all his activities.” My activities—National Honor Society, volunteer hours, architecture club—apparently didn’t move on four wheels.

When relatives visited, my room transformed into the “flex space” Mom admired in listings. My bed became a guest bed; my drawers became community property; the living room sofa became mine for the night. Adam’s room stayed sacrosanct, a museum of privacy. “Girls adapt better,” Mom said, as if quoting a parenting book that never met me.

Architecture saved me like a door that only appears when you press your hand to the right stretch of wall. At lunch I sketched mansard roofs and steel arches; in the garage I cut cardboard until my fingers wore the memory of straight edges. I checked out library books about Wright and Hadid and the bronzed bones of cities that outlasted the people who named them. When the acceptance letter came—from a respected program with a partial scholarship—I held it like a passport out of a minor country. Sixty percent tuition covered. Forty percent cliff.

“We can’t help,” Dad said, in the tone he used to announce policy changes. “We need to save for Adam.”

Adam’s transcript was a shrug wearing a hoodie. College for him was an aesthetic, not a plan. I picked up three jobs: library assistant, campus café, studio tech. I slept four hours, cradled my GPA at 3.8, and counted dollars with my eyes. During spring break of sophomore year, I came home and found photos of Adam in Rome and Paris, leaning on balustrades he couldn’t pronounce. “We used some of your college money,” Mom said, the words slipping as if they wanted out, “because Adam needed this experience for his personal growth.”

There is a kind of silence that arrives when the truth drops like a wrench through a chandelier. Then everything spoke at once—two decades of dusted-off hurts finding their voices. I said the words our house had trained me never to say: You favored him. You diminished me. You used what was promised to my education to flatten my future into his vacation. Dad’s face went a color I remembered from parent-teacher nights when teachers suggested Adam do homework. “If you don’t like how we parent, you can leave,” he said.

“Okay,” I said, and felt a clean click inside me, like a latch finally finding its strike plate.

No one offered me a suitcase, so I packed in black garbage bags—the choreography of people who weren’t planned for. Adam watched from his doorway, expression blank as primer paint. My parents did not open their bedroom door. When I pulled out of the driveway at twenty, the house was a posed photograph where I had been erased. In the rearview mirror Adam raised a hand half an inch. He didn’t come outside.

The American night can be kind and it can be merciless. Walmart parking lots are bright as operating rooms; you learn to rotate among them so no one recognizes your car. You fold your body to fit a Civic’s angles and discover which vertebra protests last. In the mornings you walk into the campus gym, swallow the shame like a vitamin, shower fast, dry your hair under the industrial blower, and pretend you haven’t been sleeping under sodium lights. Your textbooks live under the seat. Your ID rides in your bra. You figure out how to close your eyes in the library without falling fully into sleep.

One night in the studio, Lucia—sharp-eyed, sun-warm, an international student who carried laughter like a pocket radio—caught me washing my hair in the sink. She did not tilt her head the way pity tilts. “We have a storage room,” she said. “It has a window. If we put a thin mattress, it’s a room.” The mattress was a raft, humble and miraculous. Horizontal sleep felt like a luxury resort.

Eleanor found me next. She was a professor who could read a drawing the way a pathologist reads a slide. It was past midnight. I was refining a roofline like it might save me, because in a way it would. She sat. “You solve multiple problems with one gesture,” she said, tapping a curve I’d labored over. “That’s what people learn when they’ve had to work with limited resources.” The accuracy of that sentence undid me. She didn’t ask for the story beneath it; she handed me a tissue and a card. “Westlake Architecture needs an intern who thinks differently. The pay is modest. The experience won’t be.”

The internship was a suspension bridge bolted to new rock. Days: lectures, then stacks of books to shelve. Late afternoons: Westlake, where models smelled of glue and ambition. Nights: café shifts and studio, the pencil’s whisper becoming my second heartbeat. I moved from the storage room to a shared bedroom and learned how to keep exhaustion from turning into bitterness. The alternative—quitting and proving my parents right—wasn’t an alternative.

Graduation arrived like a gentle mirage made real. I crossed the stage and heard a chair creak louder than clapping. Empty seats marked “Family” sat in the sun as if waiting for better actors. Eleanor stood and clapped like hail on tin, sharp and certain; Lucia’s “Cass!” arced across the quad. Afterward, Eleanor and her husband James—a software engineer with a voice like a porch light—took me to dinner. Kale salad, roast chicken, an apple pie that tasted like the opposite of leaving. “We’re proud of you,” James said, and the sentence stayed with me, a stone for my pocket.

My first years in the field were fog and freight: modest paychecks, long deadlines, older architects who spoke in the passive voice about decisions they’d already made. I shared apartments with people who labeled butter. I saved with the ferocity of someone who remembers counting quarters for laundry. Promotions felt like extra stairs that appear where you thought the landing ended. At Eleanor’s insistence I found Dr. Mitchell, a therapist who helped me rename old ghosts. Favoritism became a system, not a verdict on my worth. Abandonment became their limit, not my defect. Sessions gave me tools for grief that didn’t look like rage, and rage that didn’t look like self-harm.

Eight years after the trash bags, I was handed a key. The house was twenty minutes outside the city, a lakeside pocket past a polite HOA sign and a 20 mph speed limit. Good bones: sturdy framing, a roof with miles to go, scarred floors begging to be sanded. I knocked down the wall between kitchen and dining. I cut a light well into the hallway so the afternoon could pour in unhindered. I slid glass toward the deck, hung string lights between trees that had watched other families forget each other, and set maple cabinets with quiet grain. When I turned the key and stepped into the bright, empty living room, Oregon sun laid itself across the floors and I cried like someone who had just met their own future. From the backseat of a Civic to a dock with a kayak and a view that made the word “home” feel rightly expensive—say what you want about this country; it will break you in its indifference and then let you build if you refuse to stop.

Silence from my biological family was both blade and bandage. No birthdays. No holidays. Not a single “Are you alive?” text. Some days the absence hurt worse than a fight might have; other days the distance felt like insulation I’d installed myself. I built new traditions with Eleanor, James, and Lucia: Thanksgiving with Italian stuffing; Christmas bulbs around the patio; New Year’s on the dock counting the echo of fireworks across the water. I believed my walls had finally thickened. Then, one April evening, my phone rang with an unknown number, and a voice I had learned not to miss reached through seven years as if crossing a street.

“Cassandra, it’s Mom.”

Those three words were spoken with the casualness of “I’m at Safeway” and landed with the weight of a subpoena.

“I’m surprised,” I said, my voice steadier than the animal panic in my chest.

“Well, it’s been a while,” she offered, the understatement so large it could have its own ZIP code. No apology. No mention of black bags and a closed bedroom door. “Are you still doing that drawing thing? Architecture, right?”

“I’m a licensed architect,” I said, biting back the urge to say Google exists. My name would pull up awards, a feature in a local magazine, my firm bio: proof I had been busy becoming a person.

“That’s nice.” The words skittered off like cheap beads. “So, I have exciting news. Adam is engaged. Bridget Williams. Her father owns Prestige Auto Group—you’ve seen the dealerships around the Pacific Northwest. Wonderful family, very connected.”

Of course the golden child had located a constellation that owned its own gravity.

“The wedding is June 12,” she continued, smooth as an empty freeway. “Three-day celebration, very exclusive.”

“Good for them,” I said, waiting for the reason she had broken silence.

“The Lakeside Country Club double-booked, and the other party has seniority. But we found an even better option. We saw pictures of your place—Zillow is amazing. The lake views! The yard! It’s perfect. We’ll host it at your house.”

There are moments you can hear a person’s entitlement rearrange your furniture in their mind.

“How many guests?” I asked.

“Around 150,” she said, as if one-five-zero were the same as fifteen. “Ceremony Friday evening, reception Saturday, farewell brunch Sunday. We’d need access Thursday for setup, of course. The Williamses will cover professional cleaning afterward.”

“My home is not available,” I said. The word home sat between us like a well-trained dog that wouldn’t heel for her.

“It’s time to get over the past,” she said, dropping into the tone she used to close on full-price, all-cash offers. “Family helps family. Adam would do it for you.”

Would he? The same brother who watched me pack into trash bags? The same “growth experience” beneficiary?

“That was years ago,” she snapped when I didn’t answer on schedule. “You always hold grudges. This is your chance to be part of the family again.”

“I built my own family,” I said. “People who actually care.”

Rustle. A handoff. My father’s voice, gruff, managerial, familiar as an instrument I never asked to learn: “Cassandra, don’t be difficult. This wedding is important for connections that could benefit all of us.”

“‘All of us’ doesn’t include the daughter you threw out,” I said. “You don’t get to vanish for seven years and then manage my property like it’s a conference room.”

“There could be consequences to refusing,” he said, lowering his voice the way men do when they want the world to sound dangerous. “The Williams family is very influential.”

“Are you threatening me?” I asked. It still amazed me how little had changed in him, how sure he was that pressure would bend metal.

A pause. A new voice, softer, a memory I hadn’t meant to protect: “Cass, it’s me.”

Adam. Hearing him was like catching a familiar scent in a stranger’s hallway. For a second my chest behaved like a younger chest.

“It would really help us,” he said, uncomfortable, almost boyish. “Bridget’s stressed.”

“I understand,” I said, and I meant it. “But I’m not hosting 150 strangers in my personal space. With your connections, you can find a venue.”

“Mom and Dad said you’d probably be difficult,” he tried. “Just… think about it.”

“I have,” I said. “No. Congratulations, but no.”

I ended the call with hands that shook the way they do after a sprint. Then I did what keeps me upright: I told the truth to people who treat it carefully. James and Lucia listened as if the story were a complicated piece of furniture we were assembling together. Outrage flared and cooled into something useful.

“They don’t see you as a person,” Lucia said. “They see a resource with plumbing.”

“At least now their behavior is Exhibit A,” I said. “Years of therapy and then one phone call that sums it all up.”

Morning delivered the next wave. Voicemails bloomed from numbers with last names I hadn’t said out loud in a decade. “Your poor brother,” Aunt Susan sighed. “Family first.” “We’ve been wondering where you’ve been,” Uncle Robert began, skipping over the part where he never called. It was chorus with one lyric: I was selfish for not donating my home.

I was silencing notifications when an email notification slid in with a subject line that curled its finger: about the wedding venue—sister-in-law to be.

Bridget wrote like a wedding magazine—silk verbs, satin nouns. She was “sorry about past family issues,” then pivoted to lanterns floating on my lake, a string quartet on my lawn, “your quaint home” (my photographs had never looked quaint), and the promise that “the joy of reuniting would be the greatest reward,” though there would, of course, be “compensation for any inconvenience.” She tucked in a gentle reminder about her father’s “relationships with several architectural firms in the region.”

Something in the email nudged my hands toward my phone. I opened Instagram. There was a dedicated wedding account, and there—shot from the property line like a paparazzi in polite shoes—were photos of my fence, my deck, my slate steps. The wedding website, linked in the bio, crowned a full-bleed photo of my backyard with the phrase family estate. The public page didn’t list an address; a passworded page for guests surely did. The schedule spelled out “Thursday setup,” “Friday ceremony,” “Saturday reception,” “Sunday brunch.” It assigned my primary bedroom as the bridal suite, the guest rooms to immediate family, and my living/dining to the reception transformation. Every room in my house was already labeled in their heads.

I called Adam. “Why are there photos of my property on your wedding site, and why does your timeline read like you own my deed?”

Silence. Then: “It wasn’t my idea. Mom and Dad convinced Bridget it would… work out.”

“How?” I asked. “I said no.”

“They think if everyone shows up, you won’t make a scene. You’ll feel pressured to go along rather than turn away 150 people. They told Bridget you were thrilled but like to play hard to get.”

The calculation was so naked it felt almost elegant in its cruelty. Weaponize shame. Crowd as leverage. Pretend consent.

“You knew,” I said, not a question.

“I didn’t have much choice,” he offered, the old family script returning to his tongue. “You know how they are. And Bridget’s family… they’re used to getting what they want.”

“So are ours,” I said. “Not this time. If you come, you’ll be turned away. I’m not a child you can herd with a guilt stick.”

“Cass, please—”

“For once,” I said, “you’ll need to practice disappointment.”

I booked an emergency session with Dr. Mitchell that evening. On Zoom, she sat like a lighthouse. “This is an extraordinary breach,” she said. “Your anger is information. The question is how you want to use it.”

“A part of me wants to leave town and let my locked doors do the talking,” I said. “Another part wants to stand at my gate and say the sentence I needed someone to teach me.”

“Both are valid,” she said. “Choose what aligns with your values and protects your safety.”

I set a dinner table and called in the people who keep my breath steady: James and Lucia; Thomas, my retired-judge neighbor who believes fences can be both necessary and beautiful. Thomas listened, set down his fork, and spoke in the cadence of case law. “This is trespass,” he said. “You have every legal right to prevent unauthorized use of your property.” Then he slid a name toward me: a property attorney who knows restraining orders like some people know wine.

By morning I was in Diane Hargrove’s office on NE Broadway, degrees in black frames, a window that faced a slice of soft Portland light. I told her the story. She nodded where a nod meant this will hold.

“Your property rights are unambiguous,” she said. “We’ll send a cease-and-desist to all parties—your parents, Adam, Bridget, her parents—via certified mail. File a pre-event informational report with your local police department so they understand the context. And I’ll call the lieutenant covering that shift.”

“And if they come anyway?”

“Call the police. With notice and documentation on file, response and de-escalation are cleaner.”

Clean. The kind of American word that feels like a gate that swings correctly on oiled hinges.

I hired a security company that handles festivals and bad decisions. They proposed temporary panel fencing with a controlled entrance, barricades at the drive, and two guards at the gate, one team at the lake because any Oregonian knows water is always a second door. I added cameras: driveway, dock, deck, porch; an app on my phone stitched every threshold into a grid I could monitor. Defense handled, I still needed meaning. James asked the right question: “How do you make that weekend yours?”

Hope Harbor was my answer. I’d been volunteering there—design tweaks for transitional housing, paint colors that didn’t punish the eyes, closets that fit more than a garbage bag. I called Maria Sanchez, the executive director, explained the situation without offering the soap opera. “We’ve wanted a spring fundraiser,” she said. “A small garden-party style, sixty to seventy people, raising money for the new housing build.”

“Bring it here,” I said. “Let’s put the lake to work for something that actually matters.”

We coordinated signage, a donation station, and a Welcome to Hope Harbor banner that would be impossible to misread. I knocked on neighbors’ doors with a clean one-page brief: schedule, parking plan, hotlines, and the simplest version of the truth. They listened with faces that looked like yards: tended, generous. “If you need anything,” they said, “you have us.”

I sent a short media advisory to two local outlets and a community blog: architect hosts fundraiser for youth homelessness. No drama bait. No family names. They RSVP’d because human interest stories still interest humans.

Dr. Mitchell helped me write the script for the gate: short sentences, verbs that stayed in my yard, “boundary” as both concept and the literal fence. “You’re not responsible for their feelings about your limits,” she said. “You can be firm without being cruel.”

By Thursday night, the house was ready in a way that had nothing to do with linens. The fencing traced my property like a pen drawing its facts. The cameras fed to my phone without lag. The donation iPads were charged; the string lights slept in loops over branches. I walked through every room and felt sadness, anger, and something new and clean braided together. Whatever happened, I would not be alone. Whatever happened, I would be the one to open or keep shut my own door.

Morning arrived the way it always does in Oregon—soft, gray at first, then daring to brighten as if the clouds had decided to give me a fair fight. The lake mirrored the sky in faint ripples, and my reflection floated over it: a woman who no longer flinched when her phone buzzed, a woman who had a plan. The air outside smelled like cedar and coffee. Today was the day my family would learn that I was no longer the child they could outtalk or outvote.

By 7 a.m., the security team arrived in black polos marked with discreet silver logos, setting up at the entrance to my long, tree-lined driveway. They were professional, calm, polite—the kind of people who handle chaos for a living without making it worse. I walked them through the property lines, the access points, the emergency contacts already on file with the local police department. “If anyone attempts to enter claiming to be family,” I told them, “refer them to the cease-and-desist letter. Do not let them through. I’ll handle any conversations myself.”

“Understood,” one guard said, checking his radio. “We’ll maintain the perimeter, ma’am.”

By eight, the first Hope Harbor volunteers began to arrive—students, caseworkers, young adults who had once needed the shelter’s help and now wanted to give back. They carried folding tables, donation jars, and trays of pastries donated by a bakery downtown. Maria Sanchez, the director, strode up the path with the confident smile of someone who’d spent her life convincing the world to care about people it prefers to overlook.

“Good morning, Cassandra,” she said, hugging me. “You ready for this?”

“As ready as anyone can be when expecting two very different kinds of guests,” I replied.

She laughed softly, then surveyed the lawn. “It’s beautiful here. The photos don’t do it justice. You couldn’t have chosen a better place to talk about new beginnings.”

Her words hit deeper than she realized. New beginnings. That’s what this was about, not revenge. I wanted to use what my family once weaponized—space, beauty, privilege—and redirect it into something decent.

By ten, the event space had transformed. Volunteers strung white lights across the deck railing and positioned a small podium near the lake, where sunlight now spilled in bright, forgiving strokes. Banners for Hope Harbor fluttered along the driveway fence, and signs at the gate read:

PRIVATE EVENT – FUNDRAISER FOR YOUTH HOUSING INITIATIVE

It was impossible to mistake this for a wedding venue, but I knew denial had always been my parents’ strongest skill.

At 10:15, two journalists from the Portland Chronicle arrived—one writer, one photographer. They were both young, friendly, and clearly charmed by the lakeside setup. They interviewed Maria about the organization’s work, took pictures of volunteers arranging flowers, and asked me a few questions about my connection to Hope Harbor.

“I understand you’ve been involved with the housing program for years,” the journalist said.

“Yes,” I answered carefully, keeping the focus where it belonged. “When I was in college, I experienced housing insecurity myself. Architecture is about structure, safety, and belonging, and so is this work. I want to make sure others never have to wonder where they’ll sleep while trying to build a future.”

He nodded, scribbling in his notebook. “That’s powerful. You’re doing something meaningful here.”

“I hope so,” I said, smiling—but my stomach was tightening. I kept glancing at my phone, where the live camera feed showed the road leading up to my gate. Empty for now.

At noon, the official start time for the fundraiser, a gentle crowd had gathered—donors, volunteers, a few local officials, and neighbors who had promised support. The lake sparkled as if blessing the moment. The sound of soft jazz floated from a speaker tucked behind a table, and the smell of baked bread and coffee lingered in the mild breeze.

Lucia was checking the refreshments, James was managing the guest list, and Thomas—the retired judge turned guardian angel—stood by the gate, calm as ever. Everything was in place.

At 2:30, Maria took the podium to welcome everyone, her voice steady, her Spanish accent curling warmly around the English words. She spoke about youth homelessness, about the need for transitional housing, about how every safe roof starts with someone who cares enough to build it. The crowd applauded. Donations clinked into glass jars. My heart swelled with pride that this, of all things, was happening in the house I had built from the ashes of my past.

Then, at 2:45, the first warning crackled through the security radio.

“Ms. Lewis,” the guard said—he called me by my professional name, the one on the deed—“we have incoming vehicles at the gate. About six so far, luxury SUVs and catering vans. One matches the plate number you gave us for your parents.”

The sound of those words was electric. I checked the camera feed: there they were, rolling in like a parade of entitlement. At the front, my parents’ silver SUV, then two catering trucks, and a convoy of guests stepping out in pastel dresses and tailored suits. Behind them, Adam and Bridget emerged from a white Mercedes, her wedding gown cover bag draped over one arm.

“They’re here,” I said quietly.

Maria met my eyes. “We’re with you.”

The security team stepped forward. I could see my father gesturing impatiently, my mother’s manicured hands cutting through the air. Even from the footage, I could read every movement: command, not request. The guards held their ground, pointing to the sign. My father leaned closer, his lips moving fast. My mother joined him, her expression a perfect blend of outrage and disbelief.

“Time to go,” James said, touching my shoulder.

I nodded. “Let’s end this properly.”

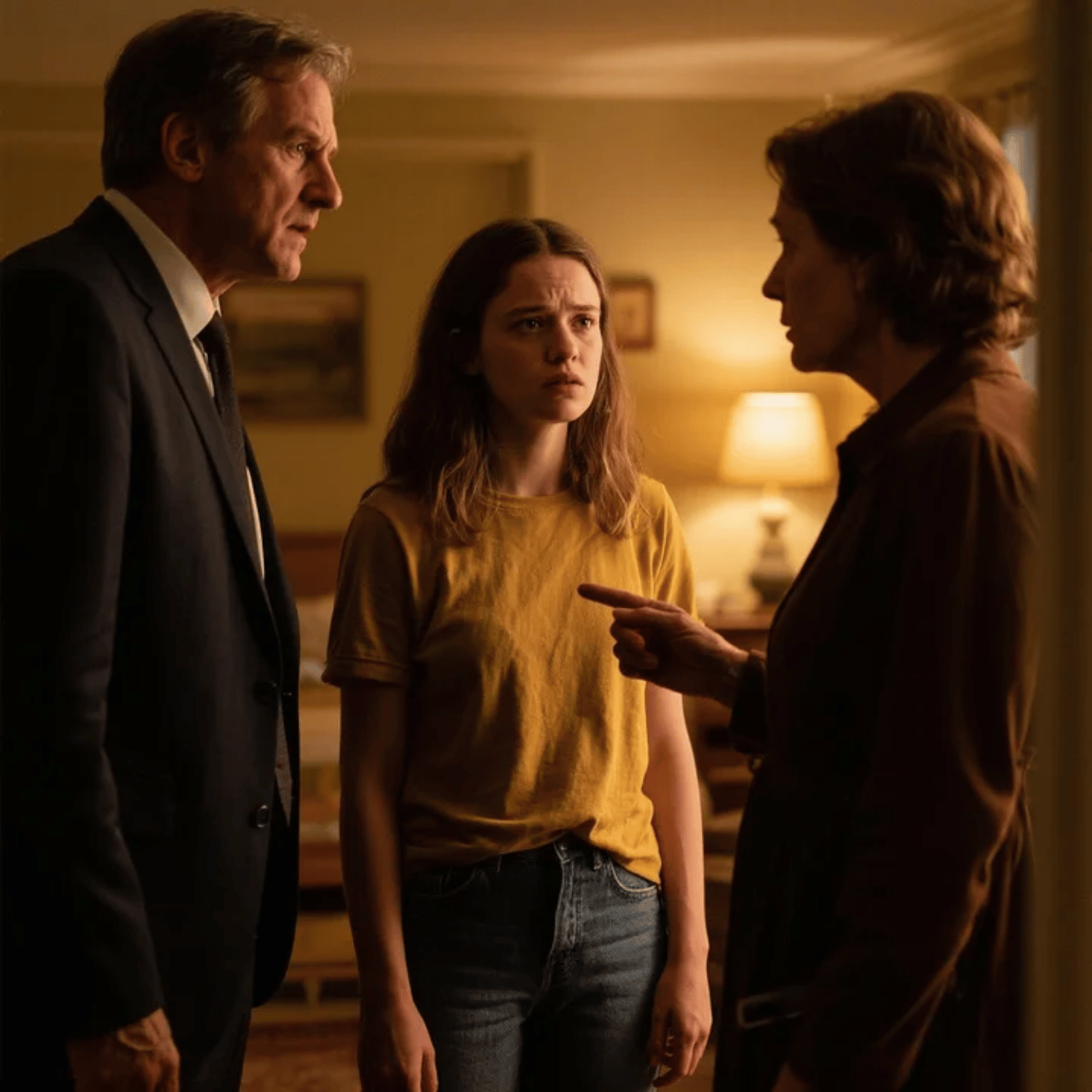

We walked toward the gate—me, James, and Lucia—our shoes crunching over gravel as the noise ahead grew sharper. By the time I arrived, my father was mid-argument with one of the guards.

“This is a private family event!” he was saying, voice booming with practiced authority. “We have permission from the homeowner.”

The guard’s response was even, professional. “Sir, the homeowner has explicitly denied that claim. You need to leave.”

And then my father turned. When his eyes met mine, something like surprise flashed there—maybe he’d expected me to hide behind curtains while he bulldozed through.

“Cassandra,” he said, switching to that low, commanding tone he used on hospital staff. “Enough of this nonsense. We have guests waiting. Open the gate.”

I stopped two feet away, the fence between us. “This is not nonsense. This is my home, and it’s being used today for the Hope Harbor fundraiser, not your son’s wedding.”

A murmur rippled through the wedding party. Cameras lifted, cell phones recording. My mother’s smile froze, brittle.

“What are you talking about?” she demanded. “We’ve planned this for months. Everything’s here—the caterers, the decorations, the guests! Don’t make a scene.”

“You made the scene,” I said, calm and clear. “You lied to everyone. You told them I agreed to this when I didn’t. You received legal notice not to come, and yet here you are.”

“This is your chance to make peace,” she said through gritted teeth. “Stop embarrassing yourself.”

“Family doesn’t ambush family.” My voice cut through her words. “Family doesn’t throw their daughter out and then expect her to host a wedding to impress someone else’s parents.”

The noise shifted. Guests exchanged looks. A few stepped back, uneasy.

Bridget pushed forward in her cream dress, her fiancé trailing behind. “Do you have any idea how humiliating this is?” she hissed. “All our friends and family—”

“—were misled,” I interrupted. “By the people standing beside you. I’m sorry this happened to you, but I won’t sacrifice my boundaries to fix their lies.”

A tall man with silver hair and a stern jaw stepped forward from the crowd—Bridget’s father. “Is this true?” he asked, turning to my parents. “You told us this property was confirmed.”

My father hesitated, then attempted a smile that looked more like a grimace. “There must have been some miscommunication—”

“Miscommunication?” Mr. Williams barked. “We’re standing outside a house that clearly says PRIVATE FUNDRAISER, and you expect me to believe this was an accident?”

My mother’s eyes darted to the news van pulling up behind the wedding convoy. The reporter and cameraman from the Chronicle, already on-site for the fundraiser, had noticed the commotion and were recording from the road. The red light on the camera blinked steadily.

“Perhaps we can discuss this privately,” she said, desperate to control the optics.

“There’s nothing private about 150 uninvited guests,” I said.

My father’s jaw clenched. “Cassandra, stop this right now. These people have traveled from out of state. We’ll be liable for thousands in cancellation fees.”

“That’s unfortunate,” I replied evenly. “But it’s the consequence of planning an event at a property you don’t own and were told not to use.”

For the first time, Adam spoke. “She’s right,” he said softly. Everyone turned toward him. “Mom, Dad—she told us no. We ignored her. This isn’t fair.”

“Adam,” my mother hissed, color draining from her face, “not now.”

“Yes, now,” he said, and the tremor in his voice wasn’t weakness—it was truth finding its way out. “I’ve spent my whole life watching you bulldoze her. She said no, and you didn’t listen. I can’t keep pretending that’s okay.”

The air between us stilled. Even the lake seemed to pause.

Bridget’s parents exchanged horrified glances. “We’re leaving,” her father announced. “This is unacceptable.” He turned to his daughter. “Get in the car, Bridget.”

“But Dad—”

“Now.”

Within minutes, the convoy began to break apart—guests murmuring apologies, caterers packing up, drivers turning vehicles back toward the road. My parents stood frozen in the middle of it, the ruins of their grand plan unraveling around them.

My mother’s mascara ran slightly at the corners, but her voice was still sharp. “You’ve ruined everything,” she spat.

“No,” I said, my words steady as the ground beneath my feet. “You ruined your chance to be part of my life. I just drew the line.”

My father’s eyes narrowed, calculating even in defeat. “You’ll regret this,” he muttered.

“I regret nothing,” I replied. “Not anymore.”

They left eventually, their SUV disappearing down the drive, trailed by silence so deep it felt like air returning after a storm.

When I turned back toward my lawn, the fundraiser guests were waiting, unsure whether to resume the event. Maria stepped forward and placed a hand on my shoulder. “Are you okay?”

“I am,” I said, surprising myself with how true it felt. “Let’s continue.”

And we did.

By 4 p.m., sunlight broke fully through the clouds. The event carried on—music, laughter, the clinking of coffee cups. A few people quietly told me they admired my composure. The Chronicle reporter approached me again, cautious. “That was… quite a confrontation,” he said. “Do you want to comment?”

I looked toward the lake, where the reflection of my house shimmered beside the water. “No comment about them,” I said. “Just write about Hope Harbor. That’s what today was for.”

He nodded respectfully and turned back to his notepad.

When dusk arrived, string lights glowed over the deck like captured stars. Donations exceeded our goal by nearly double. Maria was ecstatic, hugging me as she packed up. “You turned what could’ve been chaos into something good,” she said. “That’s rare.”

“I just wanted to reclaim the story,” I answered.

By the time the last guests left, the sky was a navy wash over the water. James handed me a glass of wine and clinked it against his. “You realize you just stood your ground against an entire army of entitlement, right?”

Lucia grinned. “And raised money doing it.”

We laughed, exhaustion finally giving way to relief. The house that had nearly been taken from me—symbolically, emotionally—stood firm, brighter than before.

Later, after everyone was gone, I walked down to the dock. The lake was still, except for a few fish breaking the surface. My reflection floated there again, steadier now. Behind me, my home glowed softly through the windows, alive with purpose.

My phone buzzed—a message from Adam.

Can we talk tomorrow? Just us.

I hesitated, then typed back: Coffee shop on Main Street. 11 a.m.

The next morning was cool and quiet. The chaos had passed, leaving a kind of fragile peace. The local news site had already published a short article about the Hope Harbor fundraiser—successful, inspirational, no mention of the family drama except for one line about “a brief misunderstanding with uninvited visitors.” Social media was less delicate, of course. A few wedding guests had posted videos of the confrontation, and strangers were debating the situation online. But the overwhelming sentiment was on my side: Her house, her rules.

At exactly 11, I walked into the coffee shop. Adam was already there, sitting in a corner booth with two mugs of black coffee and an expression I’d never seen on his face before—uncertainty.

“Hey,” he said when I sat down.

“Hey.”

For a moment we just looked at each other. He was still the brother I remembered—same eyes, same nervous smile—but something in him had cracked open.

“I wanted to say I’m sorry,” he said quickly. “Not just for yesterday. For everything. For watching them throw you out and pretending it wasn’t my fault, for taking what they gave me and knowing it should’ve been yours too.”

His words hit like unexpected warmth, both healing and painful.

“I always knew it was wrong,” he continued, voice shaking. “I just didn’t know how to stop it. When you left, I thought they’d change. They didn’t. And I let it happen.”

I took a slow sip of coffee. “You could have reached out.”

“I should have,” he admitted. “I was scared to lose their approval. That’s the truth. But after yesterday… I can’t unsee it anymore. They lied to everyone, even to me. Bridget saw it too. The wedding’s off for now.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and I meant it—not for the loss of spectacle, but for what it must feel like to realize your whole foundation was built on someone else’s back.

He nodded. “I started therapy a few months ago,” he said, surprising me. “Bridget pushed me into it. Yesterday, watching them, it was like seeing everything we grew up with from the outside. I finally understood what you went through.”

For the first time in years, I felt something fragile and new between us—empathy instead of competition.

“Therapy helps,” I said quietly. “It doesn’t fix everything, but it helps you stop believing their version of the story.”

We talked for nearly two hours—about childhood memories we’d both rewritten in our minds, about how he was learning to see our parents as people rather than gods, about how guilt doesn’t have to mean punishment.

Before we parted, he asked softly, “Can we try to stay in touch? Not about them. Just… us?”

I thought about it for a long moment. “Maybe,” I said. “But it has to be on new terms. Clear boundaries. No triangulating through Mom and Dad.”

“Agreed,” he said immediately. “Just you and me.”

When we stood to leave, he hesitated, then hugged me—a real hug, not the awkward half-pat of our teenage years. It was small, imperfect, but honest.

In the following weeks, my parents tried every trick left in their arsenal. They sent letters threatening lawsuits for “emotional distress.” Diane handled them effortlessly—“frivolous,” she called it, and they disappeared into legal dust. They called my employer to spread rumors, but my reputation and portfolio stood like reinforced concrete. When they realized their power had finally evaporated, they turned to the only weapon they had left: silence. This time, it didn’t hurt.

Instead, life filled the space they vacated. The Hope Harbor fundraiser gained local traction, and I joined their advisory board, helping design affordable housing units for youth transitioning out of shelters. The Chronicle ran a follow-up article about “Architects Building Hope.” No mention of weddings, just work that mattered.

Adam and I met for coffee every few weeks. He was still learning, still unlearning. We talked about therapy, about family patterns, about how it feels to grow a spine later than you should. We didn’t force closeness, but we built something fragile and real—a new structure with strong beams.

Six months later, on the anniversary of the fundraiser, I hosted another gathering at my house—smaller this time, just James, Lucia, Thomas, and a few friends who had stood by me through it all. We ate on the deck under the same string lights that had witnessed my first act of defiance.

“To boundaries,” James toasted.

“To chosen family,” Lucia added.

I raised my glass last. “To writing our own stories.”

The lake reflected the lights like quiet applause. For the first time, I felt free—not because I had won, but because I no longer needed to fight. My home was mine, my peace intact, my story reclaimed.

In refusing to host my brother’s wedding, I had hosted something far more important: my own liberation.

And that, finally, was enough.