The laugh of the judge cracked across the American courtroom like a gunshot.

It bounced off the high ceilings, the dark wood, the faded flag in the corner. It rolled over the rows of hard benches and landed on the shoulders of a young Black man standing alone at the defense table.

“Son,” the judge said, his voice a slow, satisfied drawl, “why don’t you sit down and wait for a real lawyer to show up?”

The judge’s robe was black. His heart was blacker.

To him, this was just another ordinary morning in a county courthouse somewhere on the East Coast of the United States. Just another file. Just another Black kid. Just another easy conviction.

He had no idea he had just made the biggest mistake of his career.

Because the “kid” he was laughing at—this skinny Black man in a sharp navy suit with no tie and too much calm in his eyes—was not someone’s nervous little brother.

He was Elijah Vance.

Twenty-four years old. Yale Law School graduate at twenty-two. A brand-new member of the state bar. Founder of a tiny nonprofit called the Vance Justice Initiative.

And Elijah wasn’t just there to win a case.

He was there to end a judge.

Department 12 of the Bridgeport County Superior Court in the United States was not a room. It was a kingdom. And for thirty-four years, Judge Arthur Harrington had been its king.

The place looked like it had been designed inside his ego. Dark mahogany paneled the walls, polished so many times the grain had gone glassy. The wood was scarred in places, but in a proud, museum-piece way, like those marks were proof of how long this courtroom had been breaking people.

The air was heavy with paper dust and floor polish and stale coffee that had died in its pot hours ago. High, grimy windows let in thin strips of late-morning light that tried and mostly failed to push back the gloom.

Above the bench, in that dim, struggling light, towered a bronze statue of Lady Justice: scales in one hand, sword in the other, blindfold over her face.

In Harrington’s mind, she wasn’t blind at all. She was winking at him.

He was sixty-eight, tall, broad-shouldered, and stiff as a marble column. Silver hair, perfectly combed. A long, Roman profile that would have looked good stamped on a coin. His eyes were the pale color of winter sky over dirty snow.

In his own personal mythology, he was not biased. He was a man of order. Of rules. Of “how we’ve always done it.”

It was just a coincidence, he told himself, that those rules always seemed to land hardest on people who didn’t look like him—and keep people who did look like him safe, promoted, and very comfortable.

He adjusted his robe, settled back into his high-backed chair, and looked down over his kingdom.

“What’s first on my docket this morning, Mr. Bailiff?” he boomed, his voice a practiced theater baritone trained to shut down interruptions.

The bailiff checked his clipboard. “First up, Your Honor, is The People of the State of—” he rattled off the jurisdiction “—versus Jamal Washington. Case number 77-4-TASA-9B. One count of Penal Code 243(c): assault on a peace officer.”

“Ah,” Harrington said, and the sound was a little sigh of pleasure. “Another two-forty-three. We’ll have this wrapped up before the ten o’clock break.”

He shuffled his stack of papers, scanning for the file. His eyes drifted to the defense table.

It was mostly empty.

The defendant sat alone.

Jamal Washington was nineteen, but he looked younger. He was drowning in a charcoal suit two sizes too big, the kind of suit a mother buys from a discount rack the night before court because the saleswoman says, “Judges like to see a young man in a suit.”

He was thin. His brown hands gripped the table. His eyes were fixed on a scuffed spot in the linoleum as if staring hard enough might let him fall straight through it.

To Harrington, Jamal wasn’t a student. He wasn’t someone’s son, someone’s whole world, standing there terrified in a borrowed tie.

He was a type. A demographic. A statistic.

He was one of them.

“Mr. Washington,” Harrington barked, and Jamal flinched like he’d been slapped. “Where is your counsel? The public defender’s office is already a disorganized mess. I will not have them wasting this court’s valuable time.”

“I– I don’t know, Your Honor,” Jamal whispered. His voice cracked on the word “Honor.”

On the other side of the courtroom, at the prosecution table, Assistant District Attorney Sarah Jenkins snapped her briefcase shut with a decisive click.

She looked like she’d been poured into her job straight from a law school brochure. Late thirties, sharp jawline, blond hair pulled into a severe bun that screamed “future candidate for higher office,” and a gray pantsuit tailored to absolute perfection. No wrinkles. No hesitation.

She and Harrington had an understanding, the kind that never needed to be spoken out loud. She brought him clean convictions. He gave her smooth hearings, friendly rulings, and a clear path to the kind of political future that started in a county courthouse and ended in Washington, D.C.

“Your Honor,” Jenkins said, her voice crisp and confident, “the People are ready. My first witness is present. We believe this is a straightforward case. Officer Riley, a decorated ten-year veteran, was assaulted by the defendant during a lawful stop.”

“Of course he was,” Harrington muttered, just loud enough for the court reporter to hear and pretend she hadn’t. “Of course.”

He looked back at Jamal with a tight little smile. “Well, son, it appears you’re on your own again. I can—”

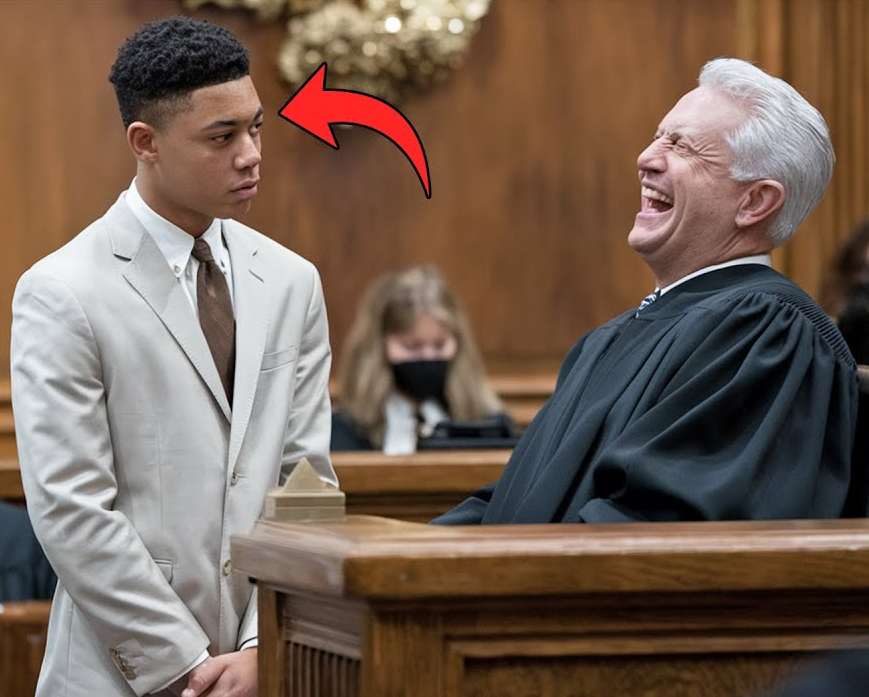

The heavy double doors at the back of the courtroom swung open with a drawn-out metallic groan.

Heads turned.

A young man paused in the doorway, outlined by the brighter light of the hallway. He was Black. Very young. Sharp as a blade.

He wore a slim-fit navy suit that actually fit him, the kind you see in glossy ads for tech startups, not in the grim halls of criminal court. His white shirt was open at the collar, no tie, like he had better things to do than suffocate for appearances.

Thick-rimmed glasses framed eyes that were focused and alert. In his hand was a sleek, modern leather briefcase, more Silicon Valley than county courthouse.

He stood there for half a second, taking in the room.

Harrington squinted down at him. All he saw was a kid. A college student who’d wandered in on a field trip. Maybe here to gawk at “real-life justice” before heading back to campus.

“The gallery is for observers, son,” Harrington said, irritation curling under his words. “And take your hat off.”

He paused, realized the young man wasn’t wearing one, and frowned.

“Fine. Just sit down and be quiet if you’re here to watch your friend.”

The young man didn’t move toward the benches.

He started walking forward.

His hard-soled shoes clicked on the polished marble floor in a measured rhythm that somehow sounded like it belonged in a bigger courtroom, a bigger city, a bigger fight.

Click. Click. Click.

He passed the public gallery. Passed the swinging half-door that separated spectators from the battlefield.

“Sir,” the bailiff said, stepping into his path. “This area is for—”

The young man walked right past him as if the man were just another piece of courthouse furniture. He stopped at the defense table, set his briefcase down with a soft, final thud, and flipped open the brass latches in one smooth motion.

He took out a neatly organized file folder, nothing else. He turned to Jamal and gave him a small, steady nod that said, without a word, I’m here. You’re not alone anymore.

Jamal stared at him like he was seeing sunlight for the first time in days.

Harrington felt confusion, then annoyance, then something hotter curling under his ribs.

“Young man,” he said, his tone darkening, “I am about ten seconds away from holding you in contempt. What in the world do you think you are doing?”

The young man turned toward the bench.

For the first time, he looked directly at the judge.

His gaze was level. Calm. No fear. None of the trained deference Harrington was used to seeing in that courtroom—not from defendants, not from rookie attorneys, not from anyone.

“Apologies for my tardiness, Your Honor,” he said. His voice was low, clear, and controlled. “The security line was longer than anticipated.”

The air in the room tightened. Even the fluorescent lights seemed to buzz louder.

At the prosecution table, Sarah Jenkins’s lips curved into a small, amused smile. This was going to be entertaining, she thought. The kid was about to be dismantled in public, and she had front-row seats.

Harrington leaned forward, a dry chuckle rumbling up from his chest. It was not a pleasant sound.

“You are who, exactly?” he asked, letting the disdain drip.

The young man buttoned his suit jacket with deliberate care.

“My name is Elijah Vance, Your Honor,” he said. “And I am counsel for the defense, representing Mr. Jamal Washington.”

Silence fell over Department 12 like a dropped curtain.

No shuffling. No whispering. Just the hum of tired lights and the faint scratch of the court reporter’s pen.

Harrington’s face, usually the faint color of worn paper, began to flush a mottled red. It crawled up his neck, across his cheeks, all the way to the carefully combed hairline.

“You are what?” he managed.

Across the room, Jenkins’s smirk evaporated. She had also assumed he was a family member, maybe a younger brother. Now she was staring at him with sharp new interest.

Elijah stood straight, like he had steel rods in his spine.

“Elijah Vance,” he repeated. “V-a-n-c-e. I am a member in good standing of the State Bar, number 9045082. I’ve filed my substitution of counsel with the clerk. If your docket is not updated, I’d suggest, respectfully, that you speak with your staff.”

Harrington made a clumsy grab for his stack of papers. Pages rattled. His fingers shook, just enough for Elijah to notice.

He hated this. He hated being wrong. He hated surprise. He especially hated being corrected in his own courtroom by someone who looked like this—young, Black, calm.

“A teenager,” he spat. The word was an accusation, not a math error. “The public defender’s office is now employing children? This is a farce. A mockery of my courtroom.”

“I’m not a child, Your Honor,” Elijah said. His face stayed neutral, but his tone sharpened. “I’m twenty-four. I graduated from Yale Law School at twenty-two. I’m not with the Public Defender’s Office. I’m with the Vance Justice Initiative. I represent Mr. Washington pro bono.”

Yale.

The name hung in the air, heavy and inconvenient.

For a second, Harrington’s brain stalled. This young man, this boy, had a better pedigree than he did. The idea tasted bitter.

“Yale,” Harrington repeated, rolling the word around in his mouth as if it were sour. “Well, then. Welcome to the real world, Mr. Vance. This is not a campus debate club. This is a courtroom in the United States of America. Your Ivy League theories won’t play well here. This is a simple case. An officer was assaulted. We have a witness. We’ll be done by noon.”

“I don’t believe we will, Your Honor,” Elijah said, almost politely.

Harrington’s fingers clenched tighter around his gavel.

“Is that so?” he said. “You’re starting off on a very bad foot, counsel. I suggest you learn your place. You are in my courtroom now.”

“My place,” Elijah said quietly, gesturing to the defense table, “is right here. Advocating for my client. Who is innocent.”

“Innocent,” Harrington barked out a single humorless laugh. “They’re all innocent, Mr. Vance. That’s the first lie they teach you, isn’t it? Fine. You want to play lawyer? Let’s play.”

He slammed the gavel once.

“We are now on the record. Ms. Jenkins, are the jurors present for voir dire?”

“They are, Your Honor,” Jenkins said. Her tone was still smooth, but inside her head, calculations were shifting. This wasn’t going to be the sleepy morning case she’d planned. This young attorney wasn’t a stumbling PD she’d seen a hundred times. He was sharper. Faster. Dangerous.

She was looking at a shark. A small one maybe, but with very sharp teeth.

“Bring them in,” Harrington ordered.

The double doors opened again. A group of eighteen potential jurors filed in, looking exactly like what they were: normal Americans dragged out of their lives to sit in judgment of a case they didn’t want and didn’t understand yet. Tired faces. Nervous hands. Curiosity. Boredom. Irritation.

Voir dire—jury selection.

To Harrington, it was a chore. A formality before the real show. To Elijah, it was the war before the war.

Jenkins went first. She didn’t need notes. She’d done this dozens of times.

“Good morning, everyone,” she began, with a warm, practiced smile. “Before we start, I want to thank you for your service. I know this is an inconvenience. But the justice system in the United States only works because citizens like you are willing to sit where you’re sitting.”

She paced gently in front of the jurors, making eye contact, reading faces. “We all know law enforcement has a very difficult job, don’t we? A dangerous, thankless job.”

She turned to juror number three, a man with a high and tight haircut and a spine straight as a rail. “Juror Number Three, Mr. Harris—first of all, thank you for your service in the military.” She said it with ease, like she’d plucked the fact from the file in her memory. “You, more than anyone, understand the importance of following orders and respecting authority. Isn’t that right?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

She moved to juror number seven, a woman in her forties with worry in her eyes. “Juror Number Seven, Ms. Davis, you live on the south side of town, correct? You’ve probably seen firsthand some of the crime in your neighborhood. You must be relieved that officers are out there every night, keeping your street safe.”

“I… I suppose so,” Ms. Davis said quietly.

Bit by bit, Jenkins built the frame she wanted: law and order, good guys and bad guys, cops at the center keeping chaos at bay. She wasn’t picking twelve strangers. She was sculpting a story in their heads before the first piece of evidence was shown.

Harrington watched, nodding occasionally, half fighting a yawn.

“Very good, Ms. Jenkins,” he said. “Mr. Vance, your turn. And please be brief. I won’t have you poisoning the pool with academic nonsense.”

Elijah rose.

Unlike Jenkins, he had no notebook in his hand. No list of questions. He just stood there for a second, looking at them. One by one.

“Good morning,” he said. “My name is Elijah Vance, and I represent Mr. Jamal Washington. He’s the young man sitting right here.”

He put a hand gently on Jamal’s shoulder.

“He’s nineteen years old. He’s a community college student. He’s never been in trouble before. And he is also, as you can see, Black.”

Harrington’s head snapped up. “Counsel, what is the relevance of that?”

Elijah looked right at him, then right back at the jurors.

“It’s the central relevance, Your Honor,” he said. “Because if my client looked different, there’s a very good chance we wouldn’t be here at all.”

He turned back to the panel.

“Juror Number Three, Mr. Harris,” Elijah said. “Ms. Jenkins asked if you respect authority. I’d like to ask you a different question, if I may.”

Harris nodded.

“Do you believe authority is infallible?” Elijah asked. “Do you believe that because someone wears a uniform, they’re incapable of making a mistake? Or of lying?”

Mr. Harris shifted in his seat. “No,” he said slowly. “Nobody’s perfect.”

“Thank you,” Elijah said.

He moved his eyes to Ms. Davis. “Juror Number Seven, Ms. Davis. Ms. Jenkins mentioned you live on the south side. You’ve seen crime. You’ve also seen policing.”

“Objection,” Jenkins snapped. “Assumes facts not in evidence. Counsel is testifying.”

“Sustained,” Harrington said immediately. “Mr. Vance, I warned you. Watch yourself.”

Elijah nodded, not looking at the judge.

“I’ll rephrase, Your Honor,” he said. “Ms. Davis, have you had any personal experiences with law enforcement that would cause you to automatically believe an officer’s testimony more than the testimony of, say, a college student?”

Ms. Davis thought about it. “No,” she said finally. Her voice was a little stronger this time. “I don’t think so.”

Elijah nodded once, like a surgeon confirming a heartbeat.

He turned to juror number eleven, a middle-aged man in a golf shirt with a neat haircut and a careful way of sitting.

“Juror Number Eleven, Mr. Alvarez,” Elijah said, glancing at the juror list. “You’re an accountant, correct?”

“Yes.”

“In your work, you can’t just feel that the numbers are right, can you?” Elijah asked. “You have to see the receipts. You have to check. You have to make sure the story the numbers are telling is actually true.”

“Absolutely,” Alvarez said.

“That,” Elijah said, “is all I’m asking you to do in this case. Not to feel that my client is innocent. Not to guess. Just to hold the prosecution to their burden. To check their math. To demand the receipts. Can you do that?”

“Yes,” the accountant said. This time, his answer was firm.

Up on the bench, Harrington was getting more irritated by the second. The kid wasn’t lecturing. He wasn’t shouting. He was doing something much worse.

He was making sense.

“Time is up, Mr. Vance,” Harrington cut in. “You’ve had your chance. We have our jury. Let’s move on. Ms. Jenkins, call your first witness.”

Elijah sat. He gave Jamal another small nod, a code between them now.

The board is set, the nod said. Now we let them move first.

For the first time since he’d been arrested, Jamal felt something other than pure, sick fear.

Hope. Just a tiny spark. But it was there.

“The People call Officer Mark Riley,” Jenkins announced.

Officer Mark Riley looked like he’d been built in a lab for the prosecution’s benefit. Mid-thirties, strong jaw, open face, body built from years of gym visits and patrol. He walked with a slight limp, just noticeable enough to suggest sacrifice without inviting too many questions.

He raised his right hand, swore to tell the truth, and took the stand like he’d done it before.

“Officer Riley,” Jenkins said in a soft, grateful tone, “thank you for your service. Could you tell the jury what happened on the night of October twelfth?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said. His voice had that calm, steady cop-tone jurors are trained by television to trust.

“We received a nine-one-one call about a suspicious individual,” he said. “Caller reported a male casing vehicles in the four-hundred block of Elmwood Avenue. My partner and I responded. We arrived, saw the defendant, Mr. Washington, matching the description.”

At the defense table, Elijah’s pen, which had been still on his yellow legal pad, made one single, precise line.

“What happened next?” Jenkins asked.

“I exited the vehicle,” Riley said. “Approached the defendant. I said, ‘Sir, I need to talk to you.’ He immediately became agitated. He puffed up, started cursing at me.”

“What did he say?” Jenkins asked.

“Objection,” Elijah said mildly. “Hearsay.”

Harrington waved a hand, annoyed. “Officer’s statements, Mr. Vance. Overru—” He stopped himself, sighed. “Fine. Sustained. Ms. Jenkins, rephrase.”

“Of course, Your Honor,” Jenkins said smoothly. “What did you do then, Officer?”

“He was acting aggressively,” Riley said, “so I attempted to place him in custody for my safety. As I reached for his arm, he tensed up, spun around, and shoved me. Hard. Right in the chest. Drove me back into my patrol car.”

He shifted in the witness chair, his limp suddenly more pronounced.

“I twisted my knee when I hit the car,” he added. “Doctor says it’ll probably never be one hundred percent again.”

Jenkins let that hang for a second.

“And your partner?” she asked. “What did he do?”

“He deployed his Taser to subdue the defendant,” Riley said. “For everyone’s safety.”

“Thank you, Officer,” Jenkins said. “No further questions.”

It was clean. Cop gets a call. Cop sees suspect. Suspect attacks cop. Partner steps in. Neat. Simple. Familiar to anyone who’s ever watched a true-crime show in the United States.

“Your witness, Mr. Vance,” Harrington said. “Try not to waste our time.”

Elijah stood.

He didn’t stalk or posture. He walked to the witness box like he was walking toward a bomb with a pair of very sharp scissors.

“Officer Riley,” Elijah said, “thank you for your testimony. I know your job is difficult. I just want to clear up a few details if I can.”

Riley smiled, relaxed. “Happy to help, counsel.”

He was looking at a young man still barely out of school. He’d dealt with worse. This would be easy.

“You said you received a nine-one-one call about a suspicious individual, correct?” Elijah asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“And that individual was described as casing vehicles?”

“Yes.”

“And you testified that my client matched the description given by the caller.”

“He did,” Riley said. His smile tightened just a fraction.

“All right,” Elijah said. “I’d like to refer to the official nine-one-one dispatch log. That’s the document that records what the caller told the dispatcher, and what the dispatcher sent to you. You’re familiar with that, I’m sure.”

“Yes.”

Elijah held up a piece of paper. “Your Honor, I’m showing the witness what’s been marked as Defense Exhibit A.”

He tapped a key on the counsel table laptop. Behind him, on the large screen used for evidence, the dispatch log appeared: a block of text, time stamps, call notes.

“Officer,” Elijah said, keeping his tone light, almost curious, “would you read the suspect description from this log? The one the dispatcher gave you over the radio.”

Riley leaned forward, squinting slightly at the screen.

“It says…” he swallowed, “White male. About six feet. Red hoodie.”

Elijah turned his head slightly, as if considering the words, then turned back to the jury.

“My client, Mr. Washington,” he said, “is a Black man. He is five-foot-nine. And when you arrested him, he was wearing”—Elijah glanced back at Jamal—“a navy jacket. Not a red hoodie.”

The jurors shifted. The accountant sat up straighter.

Elijah looked back at Riley.

“Officer,” he said, “in your professional opinion, how does a five-foot-nine Black man in a navy jacket match the description of a six-foot white man in a red hoodie?”

Riley’s friendly mask slipped.

“It was dark,” he said, too quickly. “The caller could’ve been wrong. We get bad descriptions all the time. He was… he was in the area.”

“In the area,” Elijah repeated softly.

“Yes.”

“Specifically,” Elijah said, “he was in front of his own home, wasn’t he?”

“He was outside,” Riley snapped.

“Walking from his car to his front door,” Elijah said. “The four-hundred block of Elmwood is his home address. You learned that later, didn’t you?”

Riley hesitated. “Yes.”

“So,” Elijah said, “you didn’t find him casing cars. You found him walking from his car to his front door. And despite him not matching the description in any meaningful way, you decided to stop him, correct?”

“It’s my job to investigate,” Riley said. His jaw had gone tight.

“Let’s talk about the investigation,” Elijah said. “You testified that Mr. Washington shoved you.”

“He did,” Riley snapped. “He assaulted me.”

“A shove,” Elijah said. “A hard shove. One that injured your knee, required your partner to use a Taser?”

“Yes.”

Elijah paused, then took a step closer.

“Officer,” he asked, his tone suddenly sharper, “have you ever heard the phrase ‘contempt of cop’?”

“Objection!” Jenkins practically leapt to her feet. “Argumentative. Improper.”

“Sustained,” Harrington barked. “Mr. Vance, you’re on thin ice. Move on.”

“My apologies, Your Honor,” Elijah said. He did not sound apologetic. “Let me ask it a different way.”

He looked back at Riley.

“Isn’t it true,” Elijah said, “that Mr. Washington never shoved you? That you grabbed him without cause, that he flinched away from sudden pain—like any nineteen-year-old kid would—and you turned that flinch into an excuse to arrest him for assault?”

“That’s not true,” Riley said. His voice rose. “He shoved me.”

“A shove that injured your knee,” Elijah said.

“Yes.”

Elijah looked down at his notes, then back up at the witness.

“You filed for disability benefits for that knee, didn’t you, Officer?” he asked. “A fifty-percent disability claim?”

“Yes,” Riley said. “I was injured.”

“The same knee,” Elijah said, “that you claimed a fifty-percent disability for three years ago, after a softball injury?”

For a moment, nobody breathed.

At the prosecution table, Jenkins’s face went white.

Riley stared at Elijah.

“In fact,” Elijah continued, “you’ve been on light duty for three years because of that knee, haven’t you? Which means it would’ve been impossible for you to be on active patrol the night of October twelfth. Unless you lied on your disability forms… or you’re lying now.”

“Objection!” Jenkins shouted, voice cracking. “Badgering—”

“Mr. Vance,” Harrington cut in, pinned to his chair, “where are you going with this?”

“I’m going to the truth, Your Honor,” Elijah said.

He turned to the jury, then back to the bench.

“The truth is,” he said, “Officer Mark Riley was not there that night. He never made contact with my client. The report says ‘Officer M. Riley’ and ‘Officer T. Riley.’ The prosecution brought in the one with the limp and the clean record—and left the real arresting officer out of sight.”

He faced the judge fully.

“Your Honor,” Elijah said, “the defense calls Officer Thomas Riley, Officer Mark Riley’s partner.”

The room erupted in murmurs. It clicked in everyone’s mind at once. They’d tried to swap witnesses like it was nothing. The Badge with the limp, the sympathetic one, testifying for the hothead who’d actually done the grabbing.

Jenkins looked like someone had pulled the floor out from under her.

Harrington swung his gaze toward her. “Ms. Jenkins,” he said slowly. “Is this true?”

Jenkins swallowed. “Your Honor, I— I believe—” She floundered, still staring at Riley. “It must have been a clerical error. The report said M. Riley was injured. T. Riley was the partner. It’s—”

“A clerical error?” Harrington exploded. “He just lied under oath in my courtroom. You brought me a liar and called it a slam dunk.”

“It was a slam dunk,” Jenkins said desperately. “Thomas Riley made the arrest. His testimony will be the same. The defendant assaulted him—”

“No,” Elijah cut in. His voice was quiet, but it sliced through both of them.

Both prosecutor and judge turned to him in disbelief.

“You will be quiet, Mr. Vance,” Harrington said. “This doesn’t concern—”

“It one hundred percent concerns me,” Elijah said. “And my client. And everyone in this courtroom. The district attorney’s office just presented false testimony. At best, that’s negligence. At worst, it’s a conspiracy. Ms. Jenkins, you’re looking at a Brady violation at minimum.”

“I didn’t know,” Jenkins said, her voice rising. “I did not know—”

“You didn’t know your star witness has been on desk duty for three years?” Elijah said. “You didn’t know his patrol logs didn’t put him on that street? You didn’t check? Or did you know, and hope the ‘kid lawyer’ wouldn’t notice the difference between M. Riley and T. Riley in the report?”

She had no answer.

Harrington rubbed his temples. He was corrupt, but he wasn’t stupid. Everyone in that room knew what they’d just seen.

“This is a mistrial,” he muttered. “It has to be.”

“No,” Elijah said.

Harrington’s head snapped up. “What did you say?”

“No mistrial,” Elijah said. “You’re not going to give the prosecution a second chance to fix their case. They put on their witness. He lied. I caught him. Now we move forward. Or you grant my motion for a directed verdict.”

A directed verdict. A judicial declaration that the prosecution had failed so completely that no reasonable jury could convict. An instant acquittal. A public humiliation for the district attorney’s office. A stain on Harrington’s own carefully manicured record.

He looked at Jenkins. Her career was circling the drain. He looked at Elijah. The young man was standing there, steady and relentless, and somehow holding the entire courtroom’s attention.

Harrington saw his options, one by one, and hated all of them.

“I will take the motion under advisement,” he said finally. The safest phrase a judge in trouble ever learns.

“We will resume. Ms. Jenkins, do you have any other witnesses?”

“Yes, Your Honor,” she said. Her voice trembled with anger and fear. “We have the nine-one-one caller. The eyewitness. Karen Miller. She will testify to what she saw.”

“Fine,” Harrington said. “We’ll recess for ten minutes. Then we proceed.”

He slammed the gavel. “Court is in recess.”

The walk from the courtroom to the judge’s chambers was only thirty feet, but it felt like a mile.

The air in the hallway buzzed with the fallout of what had just happened. Deputies whispering. Clerks pretending not to listen. Someone already typing up an email to “someone important” about what the hell was going on in Department 12 today.

Elijah walked with an easy stride. Jenkins walked like she might be sick. Harrington stormed.

His chambers were even darker than the courtroom. More wood. More leather. Shelves of thick law books that looked pristine enough to have never been opened. Above his massive desk hung an oil painting of himself in his robe, looking noble and stern.

He slammed the door behind them.

“What was that?” he roared, not even sitting down. “What did you bring into my courtroom?”

He wasn’t talking to Elijah. He was aiming all his rage at Jenkins.

“Your Honor, I—” she began.

“You told me this was a simple case,” he said. “You told me this was an easy win. Instead I’ve got a cop lying under oath and a defense attorney running circles around you.”

“It was a simple case,” Jenkins insisted. “The other Riley, Thomas Riley—he’s the one who made the arrest. His testimony will be the same. The defendant resisted—”

“It won’t be the same,” Elijah said quietly.

Both of them turned to him.

“You will not speak,” Harrington snapped. “This is between—”

“It absolutely involves me,” Elijah said. “And my client. And every other person who has stood in front of that bench in the last ten years without a lawyer. You put a false witness on the stand. You tried to pass him off as fact. And somebody in your office,” he looked at Jenkins, “played along.”

Harrington’s jaw worked. He was used to tantrums. He was not used to anyone talking back like this and not backing down.

“This is a mistrial,” he repeated, almost to himself.

“If you declare a mistrial,” Elijah said, “it will look exactly like what it is: a favor to the prosecution. A way to wipe the slate clean. Give them a do-over.”

“And if I grant a directed verdict,” Harrington said tightly, “I humiliate my own court.”

“You don’t humiliate your court,” Elijah said. “You admit what every juror already knows. The People have failed to prove their case. They didn’t just fail. They poisoned it.”

Harrington glared at him. “You have made a very powerful enemy today, Mr. Vance,” he said. “In the district attorney’s office. And in me. Your future in this county is over. Remember that.”

Elijah met his stare, unblinking.

“If my career is defined by not letting you bury an innocent man,” he said, “I can live with that.”

He turned and walked out.

When the recess ended, the energy in the courtroom had changed. The jurors were no longer passive. They were leaning forward, eyes sharp. They’d watched a cop get caught in a lie and leave the stand with his limp gone.

The story had shifted. They knew it.

“The People call Karen Miller,” Jenkins said.

Karen Miller was in her late fifties, with tightly permed hair and a permanent pinch in her mouth. She walked like the podium owed her respect. She was the self-appointed, unpaid sheriff of her block, the neighborhood watch captain in a modest American suburb who spent most nights looking out from behind her curtains.

“Mrs. Miller,” Jenkins said. “Can you tell the court what happened on the night of October twelfth?”

“Oh, I can,” Karen said, her voice carrying a hint of complaint. “I was watching my programs. I looked out my window and I saw him—” she pointed straight at Jamal “—lurking around Mr. Henderson’s new BMW. Just lurking.”

Jamal shrank lower in his chair.

“And what did you do then?” Jenkins asked.

“I called the police,” she said proudly. “Like any good citizen. And when the officers arrived, he got violent. Just like they do. He shoved that poor officer. Pushed him right down. It was terrible. He was like an animal.”

The word hit the air like a slap.

Jamal flinched. The jurors stiffened.

“Thank you, Mrs. Miller,” Jenkins said. “No further questions. Your witness.”

Elijah stood. This time, when he walked to the stand, he was smiling. Not a smirk. A warm, neighborly smile.

“Mrs. Miller,” he said, “thank you for coming in today. It’s clear you care a lot about your neighborhood.”

“I do,” she said, her chin lifting. “Someone has to.”

“You were watching television,” he said. “But you were also keeping an eye on the street. Is that fair to say?”

“Yes. My television is right by the front window.”

“And your house is 450 Elmwood, correct?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“And Mr. Henderson’s BMW is parked in front of 410 Elmwood. That’s four houses down.”

“That’s right.”

Elijah walked to an easel that had been rolled in during the recess. On it was a large, laminated aerial map.

“Your Honor,” he said, “this is Defense Exhibit B. A to-scale map of the four-hundred block of Elmwood.”

He pointed to a small square. “This is your house, 450. And here is 410, where Mr. Henderson parks his car. According to the city’s own records, that’s approximately one hundred and twenty yards. Does that sound about right to you?”

“I don’t know about yards,” she said, bristling. “It’s just down the street.”

“One hundred and twenty yards is roughly the length of a football field,” Elijah said. “And this was around ten-thirty at night. It was dark.”

“I have a very bright porch light,” she snapped.

“You do,” Elijah agreed immediately. “And between your porch and Mr. Henderson’s car, there is… what is this?” He tapped a large dark circle on the map.

“That’s the old oak tree,” she said warily.

“The hundred-year-old oak tree,” Elijah said. “According to the city arborist, in October, it’s very full. Lots of leaves. And there’s one streetlight on that block. Here.” He pointed. “The maintenance reports show it’s been out of service for six months.”

He looked up.

“You didn’t have those reports when you first told your story, did you, Mrs. Miller?”

Her face paled.

“I know what I saw,” she said. “He looked suspicious.”

“What you saw,” Elijah said gently, then let the gentleness fall away, “was a young Black man in a hoodie. You saw him near an expensive car. You didn’t see him get out of his own car. You didn’t see him walk to his own front door at 412 Elmwood, right next to the BMW’s spot.”

“I— he—” she stammered.

“You told the nine-one-one dispatcher there was a tall white man in a red hoodie breaking into cars, didn’t you?” Elijah asked. “That’s what the log says. That’s your voice. That’s your statement.”

Silence.

“You saw someone else earlier that night,” Elijah said. “A different person. A different race. Different clothes. Doing something that looked like a crime. You called it in. Twenty minutes later, you looked outside again and saw police officers confronting my client. And your mind blended the two scenes into one story.”

He leaned in, just enough.

“You didn’t see Jamal Washington assault an officer, did you, Mrs. Miller?”

Her mouth opened. Closed.

“It was dark,” she whispered. “I… I want to go home.”

“No further questions,” Elijah said, turning his back and walking away.

The People’s case was collapsing in real time.

Their hero cop had been exposed as a liar who wasn’t even supposed to be on the street. Their eyewitness had just admitted, in front of twelve jurors, that her memory was a tangle of fear, prejudice, and distance.

Harrington’s face was gray.

“Ms. Jenkins,” he said. “Do you have any other witnesses? Or are you prepared to rest?”

Jenkins stood up slowly. “The People rest, Your Honor,” she said. Her voice was flat.

“Very well,” Harrington said. He turned to Elijah. “Mr. Vance, does the defense wish to call any witnesses? Though I can’t imagine why you’d need to.”

The jurors chuckled. Harrington was doing what bullies always do when the tide turns: trying to sound like he’d been on the winning side all along.

“Yes, Your Honor,” Elijah said. “The defense calls Officer Thomas Riley.”

The courtroom gasped again.

Jenkins’s head whipped around so fast it you could almost hear her neck pop. “Your Honor—” she started.

“Counsel, what are you doing?” Harrington hissed. “You’ve already won. Don’t be foolish.”

“I’m not here just to win an acquittal,” Elijah said, his voice ringing clearly. “I’m here to show this jury exactly what happened on that porch on the night of October twelfth. I’m here to get justice for my client. For all of this.”

The bailiff called the name. “Officer Thomas Riley.”

The door by the side of the courtroom opened, and a different Officer Riley walked in. Shorter. Broader. Thick neck. Shaved head. A face set in a constant frown, as if the world owed him something and was late paying.

He took the stand, raised his hand, swore in. When he sat down, his stare at Elijah was openly hostile.

“Officer Riley,” Elijah said. “You were Officer Mark Riley’s partner on the night of October twelfth, correct?”

“Yeah.”

“You were the one who actually made contact with my client, Mr. Washington.”

“Yeah,” he repeated. “He was resisting.”

“Resisting what?” Elijah asked. “He wasn’t the man described in the nine-one-one call. He wasn’t breaking into cars. What exactly was he resisting?”

“He was resisting me,” Riley said. “I told him to get on the car. He wouldn’t. So I used pain compliance. Maybe they didn’t teach you that at Yale, counselor.”

There it was. The sneer. He spat the word “Yale” like it was an insult.

“So you grabbed him,” Elijah said.

“Yes.”

“And when he pulled away from sudden pain, you and your partner tackled him.”

“He was a threat,” Riley said stubbornly.

“A nineteen-year-old, one-hundred-and-forty-pound student,” Elijah said quietly, “was a threat to two trained, armed officers?”

Riley scowled. “You weren’t there.”

Elijah let it sit, then asked, “How many civilian complaints have been filed against you in the last twenty-four months, Officer?”

“Objection!” Jenkins shot to her feet. “Relevance. Prior bad acts.”

“Sustained,” Harrington said. “You know better, Mr. Vance.”

“You’re right, Your Honor,” Elijah said. “The officer’s record is not necessary.”

He turned back to Riley.

“Let’s stay here, then,” he said. “You’re aware that your patrol car is equipped with a dash camera, correct?”

Riley shifted. “Yeah.”

“And that camera is supposed to be recording whenever you’re on duty.”

“Yeah.”

“You’re also aware that you wear a body-worn microphone attached to your uniform.”

“Yeah,” he said. His voice had lost some of its swagger.

“When I filed my discovery motion for that footage,” Elijah said, addressing the jury now, “the district attorney’s office provided a ten-second, grainy, silent clip. They said the rest was corrupted. They said the audio failed.”

He reached into his pocket and held up a small silver USB drive.

“So,” Elijah continued, “I went directly to the manufacturer. The company that supplies the body-camera system to this county. All their footage is backed up on a secure cloud server, for officer integrity. I subpoenaed them.”

He looked at Harrington.

“And they sent me everything,” he said. “The full thirty-minute, high-definition file. With sound.”

Harrington just stared at him. He looked, for the first time in decades, like a man who had lost control of his own courtroom.

“Your Honor,” Elijah said, “the defense would like to play the complete video. Defense Exhibit RC.”

“No,” Jenkins said, panic in her voice. “The People object. This is— it is highly prejudicial—”

“On what grounds, Ms. Jenkins?” Harrington asked. His voice was very, very calm. Too calm.

“It— it will inflame the jury,” she said weakly.

Elijah gave a short, incredulous laugh. “It will inflame them against lies,” he said. “Not against the truth.”

Harrington looked at him, then at the jurors, then at Jenkins.

“Play the video, Mr. Vance,” he said.

Elijah nodded to the clerk. “Lights, please.”

The room dimmed. The big screen flickered to life.

The perspective was shaky—first-person body-camera footage from chest height. There was a timestamp in the corner. The date matched the night of October twelfth. Radio chatter crackled in the background.

“…looking for a white male, red hoodie…” dispatch said.

Officer Thomas Riley’s voice came through, quiet but clearly.

“White, Black, who cares,” he muttered. “We grab the first one we see and clear the call.”

The words slammed into the jury like a physical blow.

Onscreen, the patrol car rolled slowly up the block. Jamal appeared in view: backpack slung over one shoulder, keys in his hand, walking toward a modest front porch with a worn welcome mat.

Riley’s voice, amplified through the speakers, barked out.

“You. Get over here. Hands on the car.”

Jamal turned, confused. “What? I live here. I’m just—”

“I said hands on the car,” Riley shouted. “Don’t make me tell you again.”

The camera lurched. The footage showed Riley closing the distance fast. His hand shot out, grabbing Jamal and slamming him against the brick wall of his own house.

Jamal’s voice, high with fear, shouted, “You’re hurting me! I didn’t do anything!”

“Stop resisting,” Riley yelled. “Stop resisting!”

The video made it painfully clear: Jamal’s arms were pinned. He wasn’t fighting. He was just shaking.

“Hit him,” Riley’s voice said off-screen to his partner. “Light him up.”

A Taser crackled. Jamal screamed. His body jerked and crumpled to the ground.

The screen went black.

The lights came back on slowly.

Several jurors were openly crying. One wiped his face angrily, furious at his own tears.

Elijah walked back to his table. He put his hand on Jamal’s shoulder. Jamal was shaking silently, eyes fixed on the table.

“Your Honor,” Elijah said. His voice wasn’t loud. It didn’t need to be. The room was so quiet you could hear the air conditioning.

“The defense rests.”

At that point, the trial was finished in everything but name. The entire case the State had tried to sell the jury—dangerous suspect, brave officers, heroic restraint—had been ripped up and set on fire.

Closing arguments were just the last formal steps before the body was buried.

Jenkins rose to give hers. She looked down at her notes. Looked up at the video screen. Looked at the jury.

Nothing came out.

“The People waive closing,” she whispered.

“Mr. Vance,” Harrington said. His voice sounded tired. “Closing?”

Elijah stood, but he didn’t go to the podium. He stayed beside his client, one hand still on Jamal’s shoulder.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” he began, “you don’t need me to tell you what you saw and heard today. You saw the video. You heard the officer’s own words.”

He took a breath.

“You heard him say, ‘White, Black, who cares.’ You heard him say, ‘We grab the first one we see and clear the call.’ You saw my client, a nineteen-year-old American citizen, tased on his own porch for trying to go inside his own front door.”

He looked at each of them.

“This case was never about an assault on an officer,” he said. “It was about an assault on the truth. It started with a nine-one-one call from a neighbor who saw a ‘type,’ not a person. It continued with an officer who saw a ‘type,’ not a student. It was carried into this courtroom by another officer who lied on this stand under oath.”

He gestured toward the empty witness chair.

“And it almost ended,” he said, “with a wrongful conviction. Another young Black man in this country with a felony on his record for the crime of walking while existing in the wrong place, with the wrong skin, in front of the wrong judge.”

He let it hang there.

“The charge is assault on a peace officer,” Elijah said. “But the only assault that happened that night was the one committed against my client. By those officers. By this system.”

He straightened.

“I’m not asking you for sympathy. I’m asking you for accountability. For facts. For the receipts.”

He stepped back.

“Find Mr. Washington not guilty,” he said. “Not as a favor. Not as a protest. As a simple, unavoidable conclusion based on evidence.”

He sat down.

Harrington read the jury instructions in a dull monotone. When he finished, he nodded to the bailiff.

“The jury may retire to deliberate.”

They didn’t move.

Juror Number Eleven, the accountant, stood up, holding the verdict form.

“Your Honor,” he said. “We’ve reached a verdict.”

Harrington stared at him. “You… you haven’t even deliberated,” he said. His voice was thin.

“We don’t need to,” the man said.

The courtroom froze.

Harrington swallowed.

“Read the verdict,” he said quietly.

The juror unfolded the paper.

“On the one and only count,” he said, “The People versus Jamal Washington, assault on a peace officer… we, the jury, find the defendant not guilty.”

The room exploded.

Jamal collapsed forward, sobbing, clutching the table. Elijah caught him, held him, eyes closed.

Harrington hit his gavel, an old man fighting a flood with a spoon. “Order,” he said weakly. “Order. The jury is dismissed. Mr. Washington, you are free to go. This court is adjourned.”

He stood up abruptly, gathered his robe around him like a cape, and headed for the side door—not to his chambers, but to a private exit.

He was running.

It should have ended there, with a young man walking free and a courtroom buzzing. But real justice doesn’t stop at a not-guilty verdict. Not when rot runs this deep.

The real destruction of Judge Arthur Harrington hadn’t even begun.

Elijah was packing his briefcase when the bailiff approached him, looking oddly pale.

“Mr. Vance,” he said. “The judge… Judge Harrington. He’s in his chambers. He, uh… he’s demanding to see you. Alone.”

“Of course he is,” Elijah said softly.

He walked that thirty-foot hallway again, but this time he knew exactly what he was walking into.

He knocked on the heavy door.

“Get in,” a rough voice barked.

Elijah opened the door and stepped in.

The chambers, usually dim, were almost dark now. The only light came from a desk lamp casting a small circle of yellow on a sea of paperwork.

Harrington was out of his robe. It lay in a heap on the floor like something shed and forgotten. He was in his shirtsleeves, collar undone. A bottle of expensive whiskey sat open on the desk, next to a half-full glass.

“You,” Harrington said, pointing a shaking finger at him. His words were thick, slurred. “You ruined me.”

“No,” Elijah said calmly, staying near the door. “You did that yourself.”

“Thirty-four years,” Harrington shouted, slamming his fist on the desk so hard the bottle rattled. “Thirty-four years I kept order in this county. I put people like him away. I kept these streets safe. And you—” he jabbed his finger again “—come in here with your videos and your Yale and you make a joke out of my courtroom.”

“You made a mockery out of the Constitution,” Elijah said quietly. “I just pressed play.”

“The Constitution?” Harrington laughed. It was an ugly, wet sound. “The Constitution is a piece of paper. I was the law in this room. Or I was.”

He threw back the rest of his drink, grimaced, poured another.

“Do you know what you did?” he asked. “That video, that line—‘white, Black, who cares’—it’s already on the news. On every local station. They’re looping it. Sarah Jenkins is at the U.S. Attorney’s office right now, cutting a deal. She’s going to give me up to save herself. She’ll say I told her to hide the video. She’ll say I ordered it.”

Elijah said nothing.

“Well?” Harrington leaned forward, eyes narrowed. “Did I? Did I tell her to hide it, Mr. Vance?”

Elijah felt it then—the shift.

This wasn’t a drunk man venting. This was a new move. A new scheme. He was trying to draft Elijah into his last defense.

“I have no idea what you told her,” Elijah said.

“But you were here,” Harrington pressed. “You heard me yell at her in chambers. You saw I was angry. You can say that. You can say I was upset. That I knew nothing about any missing footage. You can be my witness.”

He sat back, breathing hard.

“Save me, boy,” he said. “And I’ll make you. I’ll make you a partner in everything. I’ll make you me.”

There it was. The offer. The bribe. The invitation to step over the line from advocate to accomplice.

Elijah looked at him. Really looked at him.

The man in front of him wasn’t a king anymore. He wasn’t even a judge. He was just an old man in a dark office, clutching a glass and begging someone he’d mocked that morning to rescue him from consequences.

“No, Judge,” Elijah said at last. “I’m not going to lie for you.”

“I’ll destroy you,” Harrington snarled. “You think you’re untouchable because you went to Yale? I’ll make sure you never practice law in this county again.”

Elijah reached into the inside pocket of his suit jacket.

He pulled out a small, flat digital audio recorder. He pressed a button. A red light blinked.

He had been recording since he walked in.

Harrington’s eyes locked onto the tiny red glow. The color drained from his face.

“What is that?” he whispered.

“This?” Elijah said. “This is a digital recorder. And this state is a one-party consent jurisdiction. I’m one party. You’re the other. And I’ve just recorded a sitting superior court judge trying to bribe and pressure a defense attorney into covering up his own misconduct.”

“You can’t—” Harrington started.

“You were right about one thing,” Elijah said, sliding the recorder back into his pocket. “I am smart. And I do have your career in my hands.”

He moved toward the door.

“But you’re wrong about who’s going to be destroyed,” he said.

He paused with his hand on the knob and looked back one last time.

“Because I already gave the first recording to the FBI.”

Harrington stared at him.

“The one I made in the hallway this morning,” Elijah said, “when you and Ms. Jenkins were laughing about how you were going to ‘bury the kid lawyer’ and ‘get this done by lunch.’ That one.”

Whatever was holding the judge upright seemed to vanish. He sagged back in his chair, suddenly small in a room designed to make him look enormous.

“It’s over,” Elijah said simply. “Not just your career, Judge. Your whole story.”

He opened the door and stepped out into the brighter light of the corridor.

The fallout was immediate and brutal.

The next morning, every newsstand in the county—and a lot of phones across the United States—showed the same photo: Judge Arthur Harrington, hands cuffed in front of him, being led down the courthouse steps by two U.S. Marshals. His once proud shoulders were slumped. His hair was a mess. His face was buried in his hands.

The headline on the front page of the Bridgeport County Chronicle was just one word, in massive block letters.

CORRUPT.

Underneath, the subhead: “Veteran Judge Accused of Conspiracy, Rights Violations After Viral Courtroom Video.”

It didn’t stop there.

The FBI had Elijah’s audio from the hallway. They had the chambers conversation. They had the video. They had the body-cam footage. They had decades of patterns in Harrington’s rulings: defendants without lawyers railroaded, complaints from public defenders, whispers from inside the DA’s office that had never had proof.

Now they had proof.

Faced with a mountain of evidence, Harrington had no defense.

He was indicted on eighteen counts: deprivation of rights under color of law, conspiracy, obstruction of justice, bribery, and more. His robe was taken. His license was stripped. His portrait was taken down from the courthouse wall and stored in a basement somewhere, face turned to the concrete.

He pled guilty.

The sentence: twenty-five years in a federal medium-security prison. No early release. No mercy.

The man who had spent his life sending Black men to prison from the safety of the bench was now sleeping in a narrow bed surrounded by the consequences of his own work.

His name was chiseled off the “Harrington Justice Wing” at the courthouse. His pension was seized. Judges and lawyers who’d once lined up to shake his hand now pretended not to know him.

He was erased.

Sarah Jenkins did what ambitious people do when the fire gets too close. She ran.

She went to the U.S. Attorney’s office and cut a deal. She turned over emails, memos, whispers. She described back-room conversations in exquisite detail. She painted Harrington as the mastermind.

In exchange, she pleaded guilty to a single count: failure to report a felony. She lost her law license. She lost her political dreams. The woman who had once rehearsed victory speeches in the mirror for her future run for Congress was last seen drafting paperwork in the back office of a strip-mall insurance firm, her name nowhere on the door.

Officer Mark Riley, the perjurer with the limp, was indicted on assault, perjury, and conspiracy. He took a plea: eighteen months in county jail.

Officer Thomas Riley, the man whose voice had said “White, Black, who cares,” stood trial. The body-cam footage played again, this time for a different jury. He got five years in state prison.

The badge came off. The gun came away. The uniform went back to property as evidence.

The Vance Justice Initiative, which had been a one-man office operating out of a cramped room with a second-hand desk and a donated printer, suddenly found itself drowning in attention.

Donations poured in—five dollars, ten dollars, checks from local community groups, wire transfers from people across the country who had seen the video, seen Elijah’s closing, and thought, finally.

Money came from celebrities. From activists. From people who had once sat in courtrooms like Department 12 waiting for their own verdicts.

Elijah didn’t buy a better car. He didn’t move into a luxury apartment. He hired people.

He built a team of hungry young lawyers, investigators, and paralegals. He rented a bigger office five blocks from the courthouse and put the old wooden chair from his first office right in the reception area as a reminder.

Then he turned around and pointed his new army at the past.

He filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of every single defendant who had stood in front of Judge Harrington in the last ten years without an attorney. He requested records. He pulled transcripts. He dug into plea deals and sentencing sheets.

He and his team worked nights and weekends, eyes red, fingers stained with highlighter ink, combing through case after case.

The pattern was ugly, and it was clear.

People had been jailed for talking back. For “resisting.” For “loitering” and “lurking” and “failure to follow instructions.” For being poor, for being alone, for being Black or brown in front of the wrong judge.

One by one, those cases started coming back.

Appeals were filed. Convictions were overturned. Men who had lost years of their lives to a system tilted against them walked out of prison with trash bags full of their belongings and eyes squinting against sunlight they weren’t ready for.

The headlines changed.

“Dozens Freed After Harrington Review.”

“Old Convictions Fall as New Evidence Emerges.”

“Nonprofit Challenges Decade of Courtroom Abuse.”

The Vance Justice Initiative wasn’t a curiosity anymore. It was a force.

And Jamal Washington?

His record didn’t just stay clean. It was wiped. Fully expunged. The charge that had once threatened to brand him a violent felon vanished from every database.

The city’s legal department did what city legal departments do when they see a tidal wave coming. They settled.

Jamal’s civil rights lawsuit ended in a check for two and a half million dollars. No admission of wrongdoing, the paperwork said.

The video said otherwise.

With the money came choices. Jamal could have disappeared. He could have moved far away, bought a car, bought a house, tried to forget a night on his own porch when a Taser had lit up the sky.

Instead, he walked back into the Vance Justice Initiative’s new office in jeans and a T-shirt and said, “Do you need someone to answer the phones?”

They did. And more.

He started at the front desk, then moved to intake: the first person people saw when they came in with another story of a bad stop, a bad judge, a bad deal. He listened. He believed them. He took notes and passed files to the lawyers with more information than any form could have captured.

He enrolled at the state university, majoring in criminal justice. The kid who’d once sat alone at a defense table now spent his nights on a campus library floor, highlighter in hand, learning the language of the system that had almost eaten him.

Two years later, everything looked different.

A bright new courthouse had been built to replace the old decaying wing where Harrington had ruled. The wood was lighter. The windows were cleaner. Sunlight flooded the rooms.

In one of those rooms, a Black woman in her early forties sat on the bench. Her nameplate read: HON. LENA MARSHALL. She had once been a public defender. Now she wore the robe Harrington had thought was his forever.

At the defense table stood Elijah Vance.

He was twenty-six now. His suit was the same sharp style, but his presence had changed. There was a weight to him, a quiet authority.

He wasn’t speaking.

Next to him stood a young Latina woman, barely older than Jamal had been two years earlier. Her hands shook slightly as she shuffled her notes. This was her first motion, her first argument in a real courtroom in the United States, not a mock trial on campus.

She stumbled over her opening sentence. Her voice cracked. For a second, panic flashed in her eyes.

Elijah placed one hand lightly on her shoulder. Just a touch. Just enough. She looked over, saw his steady expression, that tiny nod he’d given Jamal once.

You’re not alone. You can do this.

She took a breath. Tried again.

This time, her voice held.

Judge Marshall listened with a neutral expression that was nothing like Harrington’s early smirk. The prosecutors at the other table watched with wary respect. The clerk typed. The court reporter’s fingers flew.

In the gallery, Jamal sat on a bench, a stack of case files on his lap, watching his colleague—the baby lawyer—find her footing.

Elijah said nothing.

He had already won, in a way that had nothing to do with this one case.

He wasn’t just the genius kid anymore. He was a mentor. A builder. A guardian.

He was doing what Harrington had done—but backwards. Instead of creating a kingdom to protect himself, he was building an army to protect everyone else.

One racist judge at a time.

If you made it this far, you’ve felt it: that mix of anger, satisfaction, and something else. Relief. Because in a courtroom in the United States where the outcome was supposed to be decided before anyone spoke, one person armed with the truth flipped the script.

That judge laughed because he thought he saw a boy.

He didn’t see the weapon in front of him.

He didn’t see the years at Yale, the nights studying case law, the tape recorder in the pocket, the quiet fury at a system that thinks “White, Black, who cares” is just another line on a dispatch log.

He didn’t see the hard karma coming.

He didn’t know that his little kingdom was built on sand, and that one morning, a young man with a navy suit and a calm voice would walk in, say “Good morning, Your Honor,” and bring the whole thing crashing down.

If you believe in justice—real justice, not the kind printed on banners—share this story with someone who needs to hear it.

Because this isn’t just one courthouse, one county, one judge in one corner of the United States.

It’s a blueprint.

And somewhere right now, another “king” in another old courtroom is laughing at another “kid.”

He has no idea who just walked through his door.