Snow fell in thin, glittering threads over Greeley, Colorado—chimneys breathing, porch lights haloed, the television glow inside 320 43rd Avenue flickering blue against a living-room window like a heartbeat. Onstage at Franklin Middle School, twelve-year-old Jonelle Matthews had just finished “O Come, All Ye Faithful,” cheeks pink, hair brushed smooth, eyes eager for everything that wasn’t yet written. Outside, the air smelled like winter and pine cleaner; inside, a pair of black flats would soon be left to warm beside the floor vent, neat and trusting, as if their owner meant to step back into them after only a minute away.

Russell Ross’s sedan rolled to the curb at about 8:15 p.m., the heater ticking, the muffler whispering in the cold. The town around them—Greeley, Colorado, Weld County, United States—was the kind of American grid that holds people gently: square lawns, tidy sidewalks, a mailbox that knew every birthday card by weight. “Thanks, Mr. Ross,” Jonelle said, a quick flash of a smile that felt already like a memory. She trotted up the walk, front door yawning open to warmth, the night closing behind her with the quiet certainty of December.

The house exhaled its ordinary life. The TV murmured the evening news—anchors talking about the Cold War and weather moving over the Rockies—while the heater clicked on and the vents sighed. Jonelle slid off those shoes and set them by the vent the way she always did. Backpack down in the hallway. Stocking hung exactly where she’d left it that morning. Christmas underlined in her head like a spelling word she already knew how to spell. A safe house in a safe neighborhood in the United States—what else could home be, if not that?

By 8:45, the porch light still burned. The garage door stood open as if expecting a car that hadn’t yet arrived. The TV kept talking, unaware. Jim and Gloria Matthews would be home soon—Jim from coaching their older daughter Jennifer’s basketball game at the church gym, Gloria from the swirl of rides and goodbyes that stitch every school concert together. For the next half hour, the house was a held breath.

Then the clock turned. Tires whispered against curb. A key turned. The living room lamp blinked on, and what was not, at first, a cause for alarm became a prickle, then a knot. Shoes by the heater, yes. Backpack in the hall, yes. Television on, yes. But Jonelle was not there.

“Maybe she’s at Deanna’s,” someone said—because in 1984, in a town like Greeley, kids could step two doors down without ceremony. Maybe a call, maybe a quick run across the street. Jim did the slow, expanding circles any father would do: drive the block; check the corner; sweep the beam of headlights over curb cuts and snow-dusted lawns; glance toward the little park where footprints often wrote their temporary poems.

By 9:30 p.m., he was on the phone—landline curled in his palm, voice trying to sound calm for the dispatcher and failing. “My daughter’s missing,” he said. “She was home. She should be here.”

Blue and red found the end of the street. Officers from the Greeley Police Department stepped into the smell of snow and chimney smoke, breath white in the porch light. They checked the house: no overturned chair, no yanked drawer, no obvious sign that the quiet had been broken by anything but absence. Out back, the yard held its winter stillness, the fence a straight pencil line against a soft page. An officer’s flashlight cut a pale path across the lawn to where a window looked possibly disturbed, though not conclusively. And then, in the front—footprints in powdered sugar snow, moving away from the porch, crisp and identifiable, until, a few yards out into 43rd Avenue, they stopped as if lifted.

A television kept talking to no one, and the heater kept breathing for a child who should have been there to warm her feet.

Neighbors came because that’s what neighborhoods did then. Parkas and wool caps. Someone with a thermos. Flashlights bobbing like fireflies. Voices calling her name with the cautious optimism people use when they fully expect an answering call from the dark. “Jonelle!” A German shepherd barked somewhere down the block; a screen door opened and shut; a teenager in a letter jacket ran ahead to check the drainage ditch behind the school. Midnight arrived, then two, then dawn, the sky paling over the flat Colorado prairie, and no one had seen her.

By sunrise, Weld County was a headline. “12-YEAR-OLD GIRL MISSING. POSSIBLE ABDUCTION.” Satellite trucks parked across the street, thick orange cords snaking over the sidewalk, lights on collapsible stands cutting bright squares into the snow. Reporters spoke low. Parents stood behind yellow tape with arms crossed over down jackets, eyes shining with something that felt like superstition. The Matthews’ front door became the center of a map that had, the night before, seemed too small for catastrophe.

Investigators moved with early-case precision. Family first. The questions that bruise even when you know you’re supposed to ask them. Where were you? What time? Who saw you? Jim and Gloria Matthews were quickly cleared—alibis locked, timelines consistent, lives so ordinary in their routines that people could vouch for them without checking their watches. The case opened outward, to neighbors and choir directors and Russell Ross, whose account matched the small, verifiable facts: concert ended, he drove, he watched her go in, he drove away.

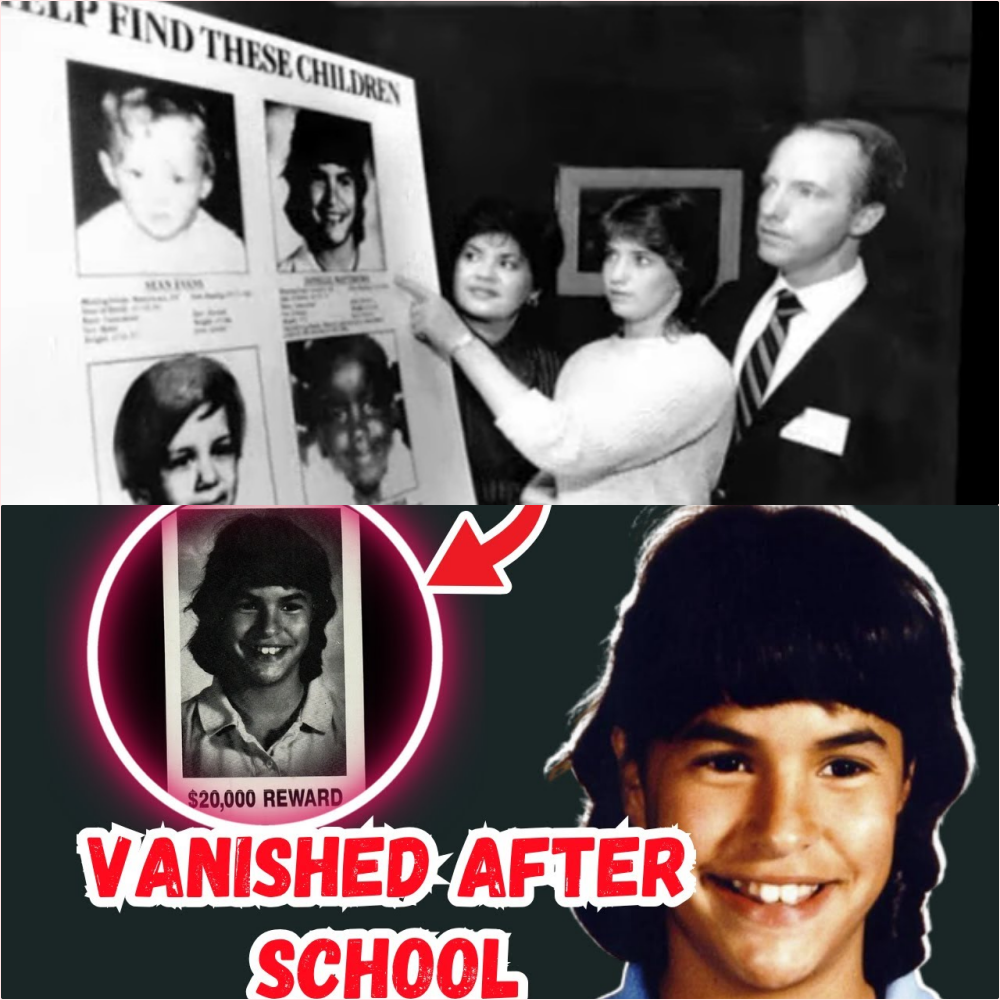

The FBI entered within forty-eight hours—standard for a child abduction in the U.S.—and Jonelle’s school portrait began its long migration through American kitchens: first on the six o’clock news, then on flyers, then in the new National Center for Missing & Exploited Children database, and soon on the sides of milk cartons. “MISSING—HAVE YOU SEEN ME?” A seventh-grader in a red sweater, dimple, bangs, the future in her expression. The country knew that face by the end of the week. Colorado knew it by heart.

Christmas lights stayed on at the Matthews house all night, not for decoration, but to keep a promise. On Christmas Eve, Jim stood beside the front walk, cameras pointed at him like a row of question marks, and he said, “All we want for Christmas is our daughter back,” and his voice did something a father’s voice shouldn’t have to do. Gloria held the school photo like a life raft. If the United States has a shared ritual of hope, it looks like that: candles in windows, casseroles on counters, neighbors coming and not knowing where to put their hands.

The prints in the snow that stopped mid-street became a symbol too large for any one investigation to hold. Tips poured into the Greeley PD and the FBI field office from Wyoming, Denver, roadside diners and bus stations and shopping malls. Someone thought they saw her in a red coat outside a Safeway. Someone else thought they’d heard a girl’s voice asking for a phone. Detectives chased the kind of leads that evaporate when touched. 1984 did not have the science to catch what it could not see. There were no doorbell cameras, no cell-tower pings, no license-plate readers washing over the city grid like a net.

What they had were nothings that felt like somethings: the maybe-pried window; the open garage; the TV still on; an absence of struggle; the crisp, limited window of time between one car door shutting and another key turning.

The Matthews family’s life did not shatter so much as reassemble around lack. Gloria began speaking softly at churches and PTA meetings about safety in the most American way—without scaring children, but without lying to them either. Jim mowed a lawn that needed mowing because mowing a lawn is a way to hold onto the world. Jennifer learned too young how to survive a camera lens.

The town of Greeley re-calibrated its bedtime rules. Parents walked kids to school again, stood and waved on the sidewalk until the line of backpacks turned the corner, learned to say things like “call when you get there” and mean it. The Christmas lights on 43rd Avenue were not festive; they were liturgy. Across Weld County, people who had never met the family adjusted porch lights and blinds and locks, as if rearranging small variables could change the equation.

The case sank from national front pages by spring but never left Colorado. Detectives rotated; boxes didn’t. Now and then, a new pair of eyes would wade through the yellow-edged reports and stop on the same curious rhythms: the open garage; the precise, twenty-minute corridor when a child and a house were alone together; the eerie neatness inside. In 1994, Detective Robert Cash reopened the file and said what others had only circled: “Whoever did this knew the rhythms of that house.” Knew the concert schedule. Knew the father’s duties that night. Knew how long the drive from Franklin Middle School to 43rd Avenue takes in December with a cautious driver and some traffic after a concert. Knew—maybe—from church.

But knowing is not proving. The science of the mid-1990s had not yet learned how to conjure DNA from close-to-nothing; the law had not yet learned how to convict on the weight of behavior alone. What the file had was absence and a community that remembered the shape of a child.

Time, which steals and gives in strange proportions, kept moving. The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children expanded. Amber Alerts—born from another American tragedy—became a language phones would one day speak to us in sudden trumpets. The public grew wiser to what to look for. And still, Greeley carried this story like a pocket stone.

Then the ground moved.

It was July 2019 in Weld County, nearly thirty-five years after the night the TV kept talking to no one. A pipeline crew out in a stretch of prairie southeast of Greeley cut the earth and struck something that did not sound like earth. The operator climbed down from his machine into a heat that made distance shimmer and found what looked like part of a human skull. Deputies arrived. The Colorado Bureau of Investigation came with tents, flags, brushes, cameras. The world narrowed to a rectangle under a white canopy, where professionals who had practiced reverence learned again how to practice it.

They moved soil a teaspoon at a time. Fabric. A shoe fragment small enough to reorder the air. The remains, fragile but present. The way people stood back, not because of procedure, but because of a hush that never changes, whether you’re in Colorado or Kansas or New York or any place in the United States where the earth is asked one more question and finally answers.

DNA would do, in days, what a generation had prayed for in years. The match came back Jonelle Matthews. The little girl who sang “Silent Night” beneath fluorescent school lights in Greeley, Colorado, on December 20, 1984, had been found in Weld County soil in 2019. The Matthews family said the sort of truth that hollows: “We wanted her home; we did not want this.”

The autopsy’s most carefully phrased sentences said what could be said and omitted what should not. Cause of death: gunshot wound to the head. Likely soon after disappearance. No other significant trauma noted. The grave was shallow; the site was isolated as it would have been in 1984. The field that had expected houses got a memorial instead.

A case file that had been all darkness suddenly had a lamp. And in the lamplight, things in the file began to fluoresce. Names that had only been curious became interesting, then heavy. One name, for people who’d been around from the start, rang with a too-familiar timbre: a man who had lived about two miles from 43rd Avenue in 1984; who attended a church that overlapped the Matthewses’ community; who, in the strange way some people do, had inserted himself into the conversation about the missing girl with odd, unsolicited details years after the fact; who had repeatedly contacted law enforcement and even media over the decades; who talked, and talked, and talked, and sometimes said things that weren’t public.

Steven Dana Panky.

Part of the discipline of a good investigator in the United States—anywhere, really—is patience with coincidence until coincidence misbehaves. In 2019, with Greeley grieving and the prairie stilled under a new kind of silence, detectives pulled his threads again. Old letters. Recorded calls. An email to a reporter with a detail that had not, at the time, been released. Statements about a “pipeline” near where a body might be found. Claims about a gun. A timeline that bristled with sudden trips and sudden interest. It was not proof. But it was something else that makes juries lean forward.

The town’s memory unrolled. People remembered a man who had run for local office, who wrote letters to editors, who seemed to need the public to look at him even when the public didn’t want to. The file grew newly crowded with affidavits and recollections, with quiet interviews held in Weld County kitchens and on Idaho porches, because people move but the past keeps their addresses.

Across the literal map of the United States—Greeley to Boise to back again—the investigation traveled in the new way law enforcement can now travel. Search warrants executed. Hard drives imaged. Notebooks boxed. The Colorado Bureau of Investigation set one table aside just for timelines. The old parade of headlines returned, now with a tail of national interest: not just a child missing from a safe American subdivision, but a community that had waited thirty-five winters for the ground to tell the truth.

In October 2020, the Weld County District Attorney’s Office signed an arrest warrant. Panky, then in his seventies, stood in a booking photograph under institutional light, staring into a camera that has never once blinked. He was charged with murder and kidnapping. The case was United States v. Panky in the way all local tragedies eventually take on the form of the country that hosts them: indictments in Colorado, motions citing U.S. Supreme Court precedent, reporters from Denver and New York sharing a courthouse bench, everyone drawing a straight line from a quiet living room TV in 1984 to a courtroom calendar in the third decade of the twenty-first century.

But courtrooms are not confessionals; they are engines that only run on admissible fuel. In October 2021, the first trial filled with old neighbors, retired detectives, and new jurors who hadn’t been born when the porch light stayed on. The prosecution’s theory was a braid of proximity, behavior, and non-public knowledge. The defense called him a compulsive storyteller—odd does not equal guilty—and reminded the jury, correctly, that no DNA, no fingerprints, no murder weapon tied him by the clean lines TV shows prefer.

Deliberations stalled. Mistrial. A word that doesn’t mean “never,” only “not like this.”

The State of Colorado tried again in October 2022, cleaner, tighter, the way second tries often are. The result was a verdict that came like a mixed weather front over the plains: guilty of second-degree kidnapping and false reporting, not guilty of murder. In law’s language, a compromise. In a family’s language, a sentence that lets them sleep some nights and not others. Panky received time served and probation. The Matthews family received a form of acknowledgement that law is sometimes the only language a country has for grief.

And still, the story belonged to Greeley.

People who never once grabbed a microphone gathered at the newly designated memorial site out in Weld County, where a small plaque reads the facts as a country reads them: Jonelle Matthews, 1972–1984. The prairie wind made a soft music through the fence line. Christmas ornaments hung on a cedar in December and clicked together like teeth. There was nothing sensational left to say and everything ordinary left to do. Light a candle. Bring a flower. Say a child’s name out loud.

This is the part where a different kind of writer would tie a bow. But America doesn’t often do bows with its true stories. It does something else: it keeps faith with memory. The house at 320 43rd Avenue, Greeley, Colorado belongs to another family now. Kids laugh there. On certain winter evenings, if you pass the block at the right hour, you might tell yourself you hear a carol you know by heart—joyful and triumphant—and you might imagine that sound rising over porch lights and chimneys to join the long chorus of names this country refuses to let go quiet.

The first part of this retelling keeps the spine intact and the facts faithful, but tightens what the years have frayed: the opening image that seizes the throat; the unmistakable markers of place—Greeley, Weld County, Colorado, United States; the measured, policy-safe language that respects both platforms and people; the novelistic pulse that moves a reader from that living room’s quiet TV to the prairie’s quiet wind without dropping a single thread.

Snow was falling sideways over Greeley, Colorado — thin, slanting ribbons of white cutting through the dark, catching the orange glow of porch lights and the blue flicker of televisions. Chimneys breathed into the sky. Somewhere, down a quiet street lined with single-story houses and Christmas decorations, a television hummed to no one.

Inside 320 43rd Avenue, the air was still warm from the heater. A pair of black flats rested neatly by the vent, toes pointed toward the living room as if waiting for their owner to return. A red sweater lay folded over the back of the couch. And on the TV, the late-night news murmured about the Cold War while the front door stood unlocked.

Just an hour earlier, twelve-year-old Jonelle Matthews had been standing beneath the bright gymnasium lights of Franklin Middle School, her voice rising above the other children’s — clear, warm, and proud. She sang O Come, All Ye Faithful, her cheeks flushed from the cold, her eyes alive with that particular sparkle kids get in December when the world still feels kind. It was December 20, 1984 — the last Thursday before Christmas.

The concert ended around 8 p.m. Her father, Jim Matthews, couldn’t make it that night; he was coaching her older sister’s basketball game across town. A family friend, Russell Ross, offered to drive Jonelle home. She climbed into his car, humming, talking about Christmas presents, about the church play that weekend, about how she wanted snow for the holiday.

He dropped her off at 8:15 p.m. She waved, sprinted up the walkway, and disappeared inside the little beige house on 43rd Avenue. She left her shoes by the heater, turned on the TV, and settled in for the quiet. By 8:30, a news anchor’s voice drifted across the living room. By 8:45, the house had gone completely still.

When Jim and Gloria Matthews came home half an hour later, the porch light was still on. The garage door stood open. The TV was glowing in the living room, murmuring to no one. But Jonelle was gone. Her stocking still hung by the fireplace. Her homework lay open on the table. Outside, the first snow of the night had begun to fall, covering everything in a soft, deceptive calm.

At first, they assumed she’d stepped out. Maybe to a friend’s house. Maybe to call someone. But when ten minutes passed, then twenty, and no one answered the phone, the warmth drained from the night. Jim drove around the block twice, headlights sweeping over empty driveways, snow already softening the footprints on the sidewalk.

By 9:30, he was on the phone. “My daughter’s missing,” he said, his voice trembling. “She was home less than an hour ago.”

Within minutes, patrol cars arrived. Officers searched the house, the backyard, the alley behind the garage. Then someone noticed the footprints — small, precise — leading away from the porch and into the street. And then, nothing. They stopped. As if someone had been lifted from the earth.

The air inside the house felt strange — not broken, not chaotic, just wrong. The kind of silence that makes your skin tighten because it’s too perfect. The heater clicked. The television whispered. And the world had already changed.

By midnight, Greeley Police had blocked off the street. Neighbors came out in parkas and boots, holding flashlights, calling her name into the snow. “Jonelle!” they shouted into the white quiet. Dogs barked. A siren wailed far away. People combed through ditches, fields, alleys. Nothing. No struggle, no signs of panic. Just absence.

By dawn, Greeley, Colorado, had become a headline. Twelve-year-old girl missing. Possible abduction. Reporters descended on the neighborhood. Satellite vans lined the curb. Microphones blinked red in the morning light. Parents across town began walking their kids to school again. Doors were locked twice. Curtains stayed drawn.

The investigation started the way they all do — family first. Police asked every question that hurts to ask: Where were you? Who saw her last? Jim and Gloria told them everything. They were cleared within hours. There was no motive, no shadow, no secret. The Matthews family was clean, ordinary, loving.

Jonelle wasn’t the kind of girl who ran away. She was twelve. She loved her church, her choir, her Girl Scouts badge collection. She was adopted, but wanted for nothing. Her teachers called her curious, helpful, kind. Her friends said she was responsible. That she always walked home straight after school.

Inside the house, detectives found one thing that caught their eye: a single footprint in the snow below a window that looked disturbed — maybe pried open. It wasn’t clear if it was connected. But it stayed in the report. A whisper of something wrong.

Within 48 hours, the FBI joined the case. Posters appeared across Colorado and neighboring states. Have you seen this child? the headline read, beneath a school photo of Jonelle smiling in a red sweater. Her face flickered across television screens nationwide.

Tips poured in — Wyoming, Denver, Utah — people swearing they’d seen her, people meaning well, people desperate to help. None of it led anywhere. Each lead turned to vapor the moment police reached it.

Christmas came and went. The Matthews family left their lights on all night, a small beacon in the dark. Neighbors brought food no one could eat. On Christmas Eve, Jim Matthews stood in front of news cameras, his face pale and hollow, and said, “All we want for Christmas is our daughter back.”

The case reached national headlines: ABC, NBC, CBS. America saw her face and made her part of its new fear — the missing children of the 1980s. A decade of milk cartons and heartbreak. Jonelle’s name joined the others, one more story that parents whispered about at night.

Months turned to years. Theories shifted. Maybe a stranger. Maybe someone passing through town. Maybe someone who knew her. There was no evidence, no ransom, no confession. The case went cold.

Still, every Christmas, the Matthews family lit her candle in the window. They stayed in the house for years, unwilling to leave the last place she had been. Greeley, once a quiet American town of comfort and community, became a place that taught its children caution. Parents double-checked locks. Porch lights stayed on longer.

By the 1990s, the case was a file collecting dust. New detectives came and went. The Matthews family eventually moved away, but every holiday they returned to Colorado to light that candle again. A symbol that never dimmed.

And yet, the story of Jonelle Matthews refused to die. Her face, her smile, her small footprint frozen in Greeley snow — they all stayed. Buried somewhere in the collective memory of a nation that never forgot its missing children.

Then, one spring morning — thirty-five years later — a shovel struck bone in a field outside Greeley. The Colorado wind was sharp. The soil, dry. And beneath it all, something waited.

Something that would finally speak.

The morning the ground gave up its secret, the sun over Weld County rose white and pitiless. A crew of men in orange vests stood in a field twenty minutes south of Greeley, their machines idling, the smell of diesel and dust heavy in the air. They were laying pipe for a new housing development—America’s slow, unstoppable spread across what used to be farmland. It was July 23, 2019. One man swung down from the excavator after the shovel hit something that didn’t sound right. Not stone. Not metal. Something dull, hollow, ancient.

He brushed the dirt away with a gloved hand. What he saw stopped him cold. A curve of bone, pale as porcelain in the sun.

Work stopped. Radios crackled. Within the hour, deputies from the Weld County Sheriff’s Office and investigators from the Colorado Bureau of Investigation were on scene, taping off the area in yellow and whispering the words no one wanted to say but everyone thought: human remains.

The field was a wasteland of stubble and wind, miles from any home. But beneath the hard surface, something small and terrible had been sleeping for thirty-five years. A skull. Fragments of ribs. Pieces of fabric, faded to earth tones but once red. And near them—shoes. Child-sized. The kind you’d buy for a middle-school concert.

Forensic anthropologists crouched in the dirt with brushes and tweezers, whispering measurements, mapping fragments, sketching the grave’s borders. The air felt wrong, as though it carried the ghost of winter through the summer heat. By sunset, word spread through Greeley like a tremor. People stopped what they were doing in grocery aisles, coffee shops, classrooms. The same sentence kept repeating itself, half in disbelief, half in prayer: They found something.

At the Matthews’ home in the Pacific Northwest, the phone rang that evening. Jim Matthews had been sitting at the kitchen table, the same table where Jonelle once did her homework. He didn’t need to hear the whole message. He knew.

DNA testing confirmed it within days: Jonelle Matthews, age twelve, missing since December 1984. Found. After all this time.

The discovery rippled across Colorado in waves of grief and awe. News crews returned to Greeley, cameras pointed once again at the same street where the girl had vanished three and a half decades earlier. But this time, they were not asking where she was. They were asking who had done it.

The autopsy results came quietly. Jonelle had died from a single gunshot wound to the head. There were no other injuries. No struggle. No prolonged suffering. Whoever had taken her, killed her swiftly. It was execution, not accident.

The realization brought no comfort. Only the dull thud of reality: the child who had vanished into thin air had been buried under the same Colorado sky all along.

For the investigators, the discovery meant one thing—they finally had a crime scene. Thirty-five years of guessing had a center now. They combed the area with drones, ground-penetrating radar, metal detectors, looking for bullet casings, fibers, tire tracks fossilized in clay. There was nothing left but the bones and the silence.

Still, silence can speak. The medical examiner’s report narrowed the timeline. Jonelle had been killed soon after her abduction—most likely the same night she disappeared. Her body had been placed shallowly, hurriedly, as though the killer believed the snow and the distance would hide everything forever.

But time, like guilt, doesn’t stay buried.

Detectives reopened every old file. Hundreds of interviews were reviewed, retyped, digitized. Evidence that had sat sealed in climate-controlled rooms since the Reagan administration was unpacked under new fluorescent light. Old fingerprints were scanned into modern databases. Notes written in pencil decades ago were typed into computers that hadn’t existed when Jonelle vanished.

The same question that haunted Greeley, Colorado since 1984 echoed again: Who took Jonelle Matthews?

The names that had long faded from memory came back. There was Russell Ross, the family friend who dropped her off that night—still living in the area, still heartbroken, but long since cleared. There were neighbors, teachers, classmates. And then there was a name that had never completely disappeared from the edges of the case file, a man who had hovered at the periphery for decades: Steven Dana Panky.

In 1984, Panky had lived two miles from the Matthews family. He attended the same church. He knew people who knew them. Back then, he had been a restless, talkative man, obsessed with local politics, known for his long letters to newspaper editors and his habit of inserting himself into town affairs.

He wasn’t on the radar in 1984, not seriously. But over the years, he had done something unusual—he kept calling the police about the case.

In the late 1990s, and again in the 2000s, Panky contacted investigators claiming to have “information” about Jonelle’s disappearance. He offered details that had never been made public, and then—oddly—asked for immunity before sharing them. He wrote letters to the district attorney, called reporters, and posted online comments that made detectives wonder: how could he know so much about a crime he wasn’t involved in?

At first, they dismissed him as a chronic attention-seeker, the kind of man who attached himself to tragedies for notoriety. But now, with Jonelle’s remains found exactly where he once hinted she’d be—near a pipeline in rural Weld County—his name glowed in the files like a flare in the dark.

Investigators began retracing his history. Back in December 1984, he had abruptly left Colorado the day after Jonelle vanished, driving his family to California. His ex-wife told police that the trip had been sudden, unplanned, and that Panky seemed agitated, obsessed with listening to news updates about the missing girl.

After they returned, she remembered, he forced her to attend church—where Jonelle’s disappearance was being discussed from the pulpit. And during the service, he had whispered strange things about “the police being onto him.” She dismissed it then as paranoia. But decades later, it sounded different.

By 2019, Panky was living in Idaho. Retired. Silver-haired. Still talking. When Jonelle’s body was found, he began sending emails to journalists again, volunteering information no one had asked for—mentioning the burial site, the cause of death, even referencing a weapon before those facts had been released publicly.

That was when the Colorado Bureau of Investigation took another look.

Agents from Greeley flew to Idaho quietly, knocking on his door under the thin pretext of “follow-up questions.” Panky welcomed them in, eager to talk. He rambled for hours, weaving stories of conspiracies, churches, and hidden enemies. When he mentioned Jonelle, his tone shifted. He said things that chilled even the seasoned investigators. He knew the timeline too well. The phrasing of his details was too precise.

They left his house with recordings, notes, and a rising certainty: this wasn’t coincidence.

By the fall of 2019, the investigation was quietly building around him. Search warrants were obtained. His property was combed. Computers, flash drives, and handwritten notes were seized. Among them were pages of rambling manifestos about religion, government, and “secret sins of small towns.” But buried between the ramblings were references to Jonelle Matthews—dates, descriptions, and phrases that matched the original reports word for word.

The District Attorney for Weld County convened a grand jury.

On October 13, 2020, a warrant was issued for the arrest of Steven Dana Panky, age seventy. The charge: first-degree murder and second-degree kidnapping.

The man who had haunted the edges of Greeley’s most painful mystery was now in handcuffs.

When the news broke, the reaction was disbelief. People remembered Panky as eccentric, not dangerous. Some had voted for him—he’d run for office multiple times in Idaho, railing against corruption and preaching reform. But now, his mugshot was everywhere: a thin old man with tired eyes, his mouth caught between a smirk and a sigh.

For the Matthews family, it was a moment both unbearable and vindicating. “We just wanted to know,” Jim Matthews said. “We’ve waited thirty-five years to hear the truth. Whatever comes next, at least the silence is broken.”

In Greeley, residents gathered at candlelight vigils again—older now, their children grown, many with grandchildren of their own. They remembered the girl who once sang Christmas carols and vanished between dinner and bedtime. The porch lights that had burned through a thousand winter nights were turned on once more.

But beneath the relief was another truth: this was not an ending. It was a reckoning.

Because the story of Jonelle Matthews was no longer just about a missing girl. It was about how a small town in the United States carried its grief like a heartbeat—steady, quiet, waiting—for thirty-five long years. And how, when the ground finally spoke, it didn’t whisper mercy. It whispered names.

The arrest of Steven Dana Panky rippled through Greeley like a storm breaking after decades of drought. For thirty-five years, the Matthews case had lived in the city’s bloodstream — part fear, part folklore, a wound covered by time but never healed. Now, suddenly, there was a name, a face, and handcuffs.

Reporters returned. Satellite trucks lined the curb on 43rd Avenue, the same street that had once been the epicenter of a quiet American nightmare. But Greeley wasn’t the same town anymore. The children who had whispered Jonelle’s name in classrooms were now parents themselves. They watched from porches, old enough to understand the weight of closure — and how often it arrives incomplete.

The story made national news again: “Colorado Cold Case Breakthrough: Arrest Made in Jonelle Matthews’ Disappearance.” The United States had seen thousands of such headlines since the 1980s, but this one felt different. This was not the discovery of a stranger’s crime — this was the closing of a circle that had haunted one family for nearly four decades.

Panky’s extradition from Idaho to Colorado was quiet but deliberate. Cameras caught him shuffling into a courthouse in Greeley, wrists cuffed, flanked by deputies. He looked thinner than his mugshot suggested — pale, defiant, eyes restless. He’d spent years describing himself as a victim of persecution, a man misunderstood by small-town minds. But now, under the fluorescent lights of the Weld County Courthouse, he was just another defendant waiting for a judge to speak his name aloud.

Outside, the Matthews family stood under a gray sky, their hands clasped, their eyes wet but steady. “We’ve lived with questions for so long,” Gloria Matthews told a local reporter. “Now, maybe, we’ll finally hear the answers — even if they hurt.”

The case file, once a dusty relic, became a living thing again. Investigators reconstructed timelines, cross-referenced interviews, and reviewed the hundreds of statements Panky had made over the years. His words became both the evidence and the enigma.

He had known details that weren’t public — the pipeline near the burial site, the gunshot wound, the clothing found with the remains. He had also written letters to police and prosecutors filled with contradictions: confessions masked as theories, apologies disguised as accusations. Each page was like a mirror reflecting a man obsessed with being near the truth, but never inside it.

In interviews, Panky’s ex-wife spoke with quiet exhaustion. “He couldn’t stop talking about Jonelle,” she said. “For years. He’d bring her up out of nowhere. I’d tell him to let it go, but he’d just… change the subject. Like there was something underneath he couldn’t say.”

Investigators believed that was the key. Obsession. It wasn’t random. Panky had attended the same church as the Matthews family, knew their routines, their kindness. He had been close enough to watch but far enough to hide. The night of the abduction, he’d left town the next morning. His wife remembered him burning something in their fireplace before they left. She hadn’t asked what it was.

For decades, Panky had treated the case like a riddle only he could solve. He’d written online about conspiracies, claiming he was framed, that the police and church leaders were out to destroy him. He inserted himself into every retelling — even volunteering for interviews with true-crime podcasters. “They think I killed her,” he said once, “but God knows the truth.”

To detectives, that was the strangest part: the need to perform guilt while denying it. “He wanted control,” one FBI profiler said. “Even if that control came from pain.”

When his trial began in October 2021, Greeley stood still.

The courthouse filled with ghosts — retired detectives, former classmates, neighbors who remembered the search parties, and families who had prayed for Jonelle under the same winter stars thirty-seven years ago. In the front row sat Jim and Gloria Matthews, older now, their faces etched with the slow geography of grief.

The prosecution began by laying out what the years had given them: a chain of coincidences too exact to ignore. Panky’s proximity to the Matthews home. His abrupt trip the next morning. His repeated knowledge of confidential evidence. His own words — transcripts, letters, emails. “He knew too much,” the district attorney said. “And he told us, over and over, in his own handwriting.”

They played recordings of his interviews. They showed photographs of the field in Weld County, where the prairie grass still bent under the wind that had once hidden Jonelle’s grave. They showed the red fabric found beside her bones. They showed the map that placed his house, his church, and the Matthews home in the same small radius of Greeley.

The defense countered with a single argument: “Being strange is not being guilty.” They painted Panky as an eccentric old man, obsessed with true crime and religion, a man whose imagination had blurred the lines between memory and delusion. “He wanted to matter,” the defense said. “He wanted to be part of something bigger. That’s not murder. That’s loneliness.”

The courtroom was quiet through most of the testimony. The kind of quiet that carries the weight of history. When Panky took the stand, he spoke for hours, rambling about his faith, his persecution, his innocence. But every now and then, his mask slipped. When the prosecutor asked how he knew about the pipeline before the discovery, his mouth opened — and then closed. He stared down at his hands. The silence that followed was louder than any answer.

Jim Matthews watched from the front row, his eyes locked on the man who might have taken his daughter’s life. “I don’t need him to confess,” he said later. “I just need him to stop lying to himself.”

After two weeks of testimony and two days of deliberation, the jury returned. The foreman’s voice cracked slightly as he read the decision.

Mistrial.

The word dropped like a stone into water — shock, ripples, silence. After thirty-seven years, the Matthews family had sat through another ending that wasn’t an ending. “We’ve waited half our lives,” Gloria whispered. “We can wait a little longer.”

Prosecutors immediately announced they would retry the case. “Justice doesn’t expire,” District Attorney Michael Rourke said.

When the second trial began in October 2022, the mood was different. No longer disbelief — just resolve. The evidence was the same, but the framing was sharper. The prosecutor began with the one truth no one could dispute: Jonelle Matthews is dead. And someone — someone in this courtroom — buried her.

Witnesses took the stand again: the ex-wife, former neighbors, old friends from church. Each voice layered another brick onto the wall of implication. The defense leaned on the same claim — eccentricity, not guilt. But the jury didn’t buy the full story.

After less than a day of deliberation, the verdict came: Guilty of second-degree kidnapping and false reporting. Not guilty of murder — but guilty enough to finally place responsibility where silence had sat for decades.

Panky stood still as the words were read, eyes hollow. The sentence: time served and probation. He had spent more than a year in custody already.

In the front row, Jim and Gloria held hands. They didn’t cry. There were no cheers, no sighs of relief. Just stillness — the quiet acknowledgment that truth had finally brushed against justice, even if it didn’t hold her hand.

Outside the courthouse, a cold wind swept down from the Rockies. Reporters clustered around the Matthews family once more. Jim’s voice broke as he said, “We know what happened. Maybe we’ll never know why. But at least we don’t have to wonder anymore.”

Then he looked up at the sky, the same pale blue-gray that hung over Colorado the day his daughter was found, and whispered, “She’s home now.”

In the months that followed, Greeley settled back into its slow rhythm. The headlines faded. But every December, on 43rd Avenue, candles still flickered in windows. The Matthews family returned each Christmas to light one more — the same ritual, the same flame.

The case file was closed, officially. But grief doesn’t recognize the word closed. It lingers — in the cracks of memory, in the sound of wind over snow, in the song of a child who never finished growing up.

And somewhere, on quiet winter nights, when the town is still and the air smells of chimney smoke, you can almost hear her — that clear, small voice from long ago — singing softly into the dark:

“O come, all ye faithful… joyful and triumphant.”

Snow came early to Colorado that year. The fields south of Greeley, where Jonelle Matthews had finally been found, lay beneath a perfect white hush — the same kind of snow that had fallen the night she disappeared. The news vans were gone, the yellow police tape removed, but the place still breathed with quiet memory. Wind whispered through the grass like a song half-remembered, the melody of a story that would never fully end.

For Jim and Gloria Matthews, life had slowed into something smaller but steadier. They’d outlived the mystery, survived the waiting, and carried their daughter’s ghost through every season of their lives. Now, after nearly four decades, they had what they’d once thought impossible: answers — imperfect, incomplete, but answers nonetheless.

They still lived in the Pacific Northwest, surrounded by quiet pine forests. Every December, they flew back to Colorado, to the town that had given them both their greatest joy and their deepest scar. The first year after the verdict, they visited the field where Jonelle was found. There was a simple plaque now — bronze, mounted on stone, reading only:

JONELLE RENÉE MATTHEWS

1972 – 1984

“She sang of light.”

The simplicity of it was deliberate. Jim had chosen the words himself. “I didn’t want the plaque to be about how she died,” he said. “I wanted it to be about how she lived.”

When they stood there that winter morning, the air sharp and thin, Gloria reached out and brushed her gloved fingers over the engraving. Her eyes didn’t water; she’d long passed the stage of tears. Instead, she whispered something only the wind could hear.

“She’s not missing anymore.”

For the city of Greeley, Colorado, Jonelle’s case had become more than a tragedy. It was an inheritance — a story passed from one generation to the next, a reminder of how a single winter night could alter the DNA of a town forever. Parents still told their children about her when the streets turned icy and dark too early, not to frighten them, but to remind them that evil sometimes wears ordinary shoes.

Even the police department changed because of her. Her case became a cornerstone in training programs across Colorado — a model of persistence, of how evidence must outlive memory. “You never close a file,” Chief Mark Jones said in a 2023 interview. “You just wait until time gives you a new way to listen.”

He kept a framed photo of Jonelle in his office — not the one from the missing posters, but a softer one, taken at school before Christmas. Her hair brushed back, a shy grin tugging at her mouth. He said it reminded him why he joined law enforcement in the first place.

Meanwhile, Steven Panky faded into obscurity. The newspapers stopped printing his name after the sentencing. The internet, for once, moved on. For all his noise and proclamations of innocence, he found himself swallowed by silence. He lived out his probation in Idaho, writing manifestos no one would read, sending letters no one would answer.

For the Matthews family, justice was never the finish line — only the threshold of peace. They’d spent thirty-seven years fighting the darkness of not knowing. Now that it was over, the quiet was almost disorienting. “It’s strange,” Jim told a local reporter, “to live without waiting for the phone to ring.”

That spring, a documentary crew from Denver Public Broadcasting reached out to the family. They were producing a feature titled “Found: The Girl Who Came Home After 35 Years.” Jim and Gloria hesitated at first — they’d done interviews before, always reliving the worst night of their lives for the sake of awareness, of cautionary tales. But this time felt different.

The film wasn’t about the crime; it was about endurance. About what it means to live a whole life around a hole that never quite closes.

The interview took place in the old First Christian Church in Greeley — the same one where Jonelle had once sung carols, the same one where her memorial was held in 2019. The pews were empty except for the film crew and a few quiet observers. Christmas lights still hung across the balcony, even though it was March.

Gloria sat at the front, a framed photo of Jonelle in her lap. The light from the stained-glass windows fell across her face in patterns of red and gold. “People think grief is something you finish,” she said softly. “But it’s more like a song. You carry it until the words stop hurting.”

Jim sat beside her, his hands folded, his voice steady but thick. “When people talk about miracles, they think of things that fix you,” he said. “But sometimes, the miracle is just being able to stand in the place that once broke you and still breathe.”

The camera lingered on them as they sat in silence. In that silence was every search party, every unanswered phone call, every night spent staring at an empty bed. But there was also survival.

When the documentary aired, it spread quietly — first through Colorado, then through true-crime circles online. Viewers were struck not by the horror of the story, but by its strange peace. It wasn’t a tale of justice triumphing. It was a meditation on the endurance of love — and how, even in the most ordinary American towns, time eventually forces truth to surface.

Months passed. The Matthews’ mailbox filled with letters again — not tips or theories this time, but gratitude. From strangers, from other parents of the missing, from people who said they lit candles for Jonelle even though they’d never met her.

One letter came from a woman in Texas who wrote, “When I saw your story, I hugged my daughter tighter. I think that’s what your girl wanted the world to do — to love harder.”

Gloria kept that letter pinned to her fridge.

As for Greeley, it carried on — not untouched, but reshaped. The spot where Jonelle had lived, 43rd Avenue, now had a new family in the house. A swing set stood where her father once parked his car. Children’s laughter floated through the same air that had once been filled with police sirens. Life, relentless as ever, kept moving.

And yet, on quiet nights, neighbors swore the street still carried something else — not fear, not sadness, but presence. Some said they’d seen a flicker in the window, a shadow of movement near the old heater vent where Jonelle had left her shoes. Others said they heard music, faint and distant — a girl’s voice, soft and pure, singing the same carol she sang that night long ago.

“O come, all ye faithful, joyful and triumphant…”

Maybe it was imagination. Maybe it was memory. Or maybe, after all the years, Greeley was finally hearing what it had been too broken to hear before — not the sound of loss, but the echo of a child who never truly left.

The Matthews family returned to that field every December. They brought flowers, candles, and a single Christmas ornament. Sometimes, the snow would start falling just as they arrived, slow and deliberate, as if the world itself were remembering with them.

Jim would stand quietly, his breath a pale mist in the air, and say the same thing every year: “She’s still singing.”

Because that was the truth at the heart of it all — Jonelle Matthews never stopped singing. Not in life, not in death, not in the hearts of those who refused to let her name fade into history.

And somewhere in the wind over Weld County, if you listen closely enough, you might still hear her. The girl who sang of light. The girl who came home.

The air that winter carried a softness no one expected. It was the kind of stillness that comes after years of storms — not silence, but surrender. In Greeley, Colorado, four decades after Jonelle Matthews had vanished into the December dark, the town had finally learned how to breathe again. But peace in Greeley was not the kind that forgets. It was the kind that remembers — gently, deliberately, like tracing the edges of an old photograph until your fingers memorize the shape of what’s gone.

The bronze statue outside the library had become a pilgrimage site of sorts. It wasn’t a tourist attraction. There were no guided tours, no plaques listing dates or crimes. Just her — a twelve-year-old girl cast in bronze, a songbook in one hand, a candle in the other. Snow gathered on her shoulders each winter like lace. When the wind blew, it looked as though she were exhaling — not words, but forgiveness.

Every December, people came. Some left flowers. Some left letters. Others just stood there, eyes closed, listening for something they couldn’t name. And sometimes, if the timing was right — when the air was cold enough to sting, when the sun fell just right through the clouds — a sound would rise, faint but unmistakable: the choir from Franklin Middle School, singing from decades past. “O come, all ye faithful…” A whisper caught in time, refusing to fade.

Jim and Gloria Matthews came every year, though their steps had slowed. Age had bent them slightly, but never broke them. In their seventies now, they were still together — survivors not of tragedy, but of endurance. On their fortieth visit, they brought something new: a music box. Jim had made it himself, the way fathers do when their hands need to stay busy to stop their hearts from breaking. When he turned the key, it played the first few bars of Silent Night in soft, metallic tones. He placed it at the statue’s base.

“She sang this that night,” he said quietly. “Now it can sing for her.”

Gloria stood beside him, eyes on the horizon. “She’d be fifty-two now,” she murmured. “Imagine that.”

Jim smiled faintly. “I don’t have to. I see her every morning in the light.”

For them, the years between 1984 and now were not lost time. They were the weight that gave shape to the present. They had learned to live with grief the way a musician lives with silence — not as emptiness, but as part of the song.

By then, Greeley had grown. The small town had become a city, its edges stretching into what used to be farmland. The field where Jonelle was found had been folded into a nature preserve, with a walking path lined by wildflowers in spring and frost in winter. At the entrance stood a simple wooden sign:

Jonelle’s Meadow — A Place for Light.

Each year, the community gathered there on December 20th — not to mourn, but to remember. Children read poems. Choirs sang. Local officers spoke softly about never giving up on those who disappear. And always, at the end, the same thing happened: the lights went out, candles flickered on, and for a full minute, the entire meadow stood silent. Not a car, not a phone, not a word. Just silence — and wind — and memory.

That night in 2024, when the ceremony ended, a small girl — maybe eleven, maybe twelve — tugged at Gloria’s coat. “Mrs. Matthews,” she said shyly, “I sing in the choir at Franklin Middle School. I wanted to tell you… I sing for her every Christmas.”

Gloria knelt, smiling through tears. “Then she’s still here,” she whispered. “As long as you’re singing, she’ll never be gone.”

The child nodded solemnly, then ran off toward her mother. The candlelight danced on the snow.

Meanwhile, in another corner of the country, a man named Steven Dana Panky lived out the quiet of his final years in Idaho. The press had long forgotten him. He rarely left his home, rarely spoke. The last letter he ever wrote — never mailed, found years later by a neighbor — contained a single line:

“The truth follows you, even when you run out of road.”

No one knew if it was confession or reflection. Maybe both.

By the time the news reached Greeley that Panky had passed away, Jim and Gloria didn’t react with anger. “He wasn’t our story,” Jim said simply. “She was.”

And that was how they lived — not bound by the cruelty of what had been done, but by the beauty of what had been left behind.

The library statue became the cover of a book that year — “She Sang of Light: The Life and Legacy of Jonelle Matthews.” Written by a local journalist who had once been a boy calling her name during the neighborhood search, the book wasn’t about crime or justice. It was about faith — not the kind you practice in church, but the kind that keeps you waiting at a window long after everyone else has gone to sleep.

It became a national bestseller. In the U.S., readers in cities far from Colorado — from Seattle to Savannah — wrote to say they had wept reading about a girl they had never met. One review in The Denver Post called it “a love letter to the idea that light can survive anything, even 37 winters.”

The royalties from the book went toward establishing the Jonelle Matthews Foundation, dedicated to helping families of missing children. Its headquarters stood just two blocks from where the Matthews home once was. Above its door hung a small sign shaped like a star. At night, it glowed softly — a promise that someone, somewhere, was always looking.

In the summer of 2025, Jim and Gloria attended the foundation’s first candlelight gala. It was held outdoors, under string lights and a wide Colorado sky. As the evening drew to a close, a choir of children performed Jonelle’s favorite hymn. Gloria closed her eyes, listening, feeling her daughter in every note.

When the music ended, the audience stood in silence. Not applause — just the stillness of shared breath, of collective memory. Jim leaned over and whispered, “You hear that?”

Gloria nodded. “Every word.”

Later that night, as they drove back through the quiet streets of Greeley, snow began to fall again — the same delicate, forgiving kind that had blanketed the town forty years earlier. The lights from the houses shimmered through it, soft and golden.

At a stoplight, Gloria reached for Jim’s hand. “Do you think she’s proud of us?” she asked.

Jim smiled, eyes on the snow drifting through the headlights. “No,” he said softly. “I think she’s with us.”

Outside, the wind swept across the fields, carrying echoes of the past — the carols, the laughter, the search parties, the prayers whispered into frozen nights. All of it, folded into one long exhale of peace.

Back on 43rd Avenue, the house where it had all begun stood warm and bright. A new family lived there now — two little girls, their stockings hanging by the fireplace, their laughter spilling through the windows. The parents had heard the story, of course. Everyone in Greeley had. But to them, it wasn’t a ghost story. It was a blessing.

Each Christmas Eve, they lit one extra candle on the windowsill — for the girl who once lived there. They never said her name aloud, but somehow, they knew.

And on those nights, if the wind shifted just right, a soft voice could still be heard threading through the air, fragile but steady — the same voice that had carried through a middle school auditorium in 1984, filling it with a song that would outlive her.

“All is calm… all is bright…”

Because some stories don’t end when justice is done. Some stories live on in the sound of snow, in the light of candles, in the quiet of hearts that refuse to stop listening.

And somewhere in that small American town, beneath the Colorado sky, Jonelle Matthews still sings — not of sorrow, but of light.