The Texas night pressed its face to the glass—humid, hush-blue, and bright as a showroom inside 1204 East Allen Avenue, Fort Worth, Texas. A video-game controller clicked in a steady heartbeat. A laugh bubbled, small and warm, from an eight-year-old boy. In the bedroom light, Atatiana “Tay” Jefferson leaned forward, eyebrows arched, the competitive spark she carried since childhood dancing across her face. On the dresser: MCAT flashcards fanned like a magician’s deck; on the bed: a half-folded throw blanket; on the wall: a paper reminder to call the clinic about her mother’s medication. This was home—Tarrant County, porch light on, late, ordinary, safe.

Across the street, James Smith watched from his window and felt a tiny burr of worry catch in his throat. The Jeffersons kept a tidy routine. Doors closed. Lights off by now. Tonight the front doors stood open like a sentence left unfinished, rectangles of gold bleeding into the dark. He debated walking over. He thought of Mrs. Carr’s health. He thought of prowlers, of how the alley swallowed sound, of every neighborhood story that started with I thought about checking and didn’t. He reached for the phone instead and dialed the non-emergency line. His words were simple as a prayer: Would you send someone to check? The doors are open. The lights are on. Just make sure they’re okay.

Inside the bedroom, another round loaded. Aunt and nephew, two controllers, one glowing scoreboard. The boy giggled at a victory. Tay smirked, conceded, queued up the next match. This was their pact: she studied, then she played; he played, then he slept. Balance. Caregiver by day, student by grit, gamer by joy, she built a bridge between all the pieces of her life and walked it without looking down.

What happened next would break that bridge in a single, irretrievable sound.

Two officers rolled in silent from the block’s far end, not parking in front like neighbors would, not knocking like neighbors do. Radios low. Flashlights cupped. Their body-worn cameras saw what the eye often misses—the skitter of light across chain-link, the scuff of a boot on St. Augustine grass, the side yard at 1204 East Allen Avenue stretched thin as a nerve. They moved as if a burglary were in progress, not a wellness check. They did not announce themselves. They did not call the family name into the open night where it could settle and soothe. They stayed behind the cast-iron fence, then slipped through the gate into the backyard where the dark deepened.

From the bedroom, Tay caught a flicker—white beam, then nothing. The boy didn’t notice; his avatar was near a checkpoint. Tay angled her head. Another slice of light feathered the blinds. She thought of her mother sleeping. She thought of the front doors. She thought of Fort Worth summers and the stories people tell when doors get left ajar—how a home can feel sturdy as a bank vault until, suddenly, it doesn’t. She rose. “Stay here, buddy,” she told the boy, her voice firm and soft all at once. She stepped closer to the window, inches of vinyl slat and double-pane glass between curiosity and danger.

Outside, the flashlight hit the glass.

A voice barked in the yard—urgent, sharp, words like thrown coins: “Put your hands up! Show me your hands!”

Less than two seconds later, a single report split the room. Time folded. The controller clattered to the floor.

Across the street, James Smith heard what he had prayed he would not: that terrible punctuation mark of a night turning into an after. Sirens came like a tide. Blue light struck the facades of the small single-story homes—the ones with concrete porches, faded lawn chairs, and hand-painted numbers. Neighbors on East Allen Avenue tumbled from doorways in sleep-wrinkled T-shirts, hands clapped to mouths, questions forming that would outlive the dawn.

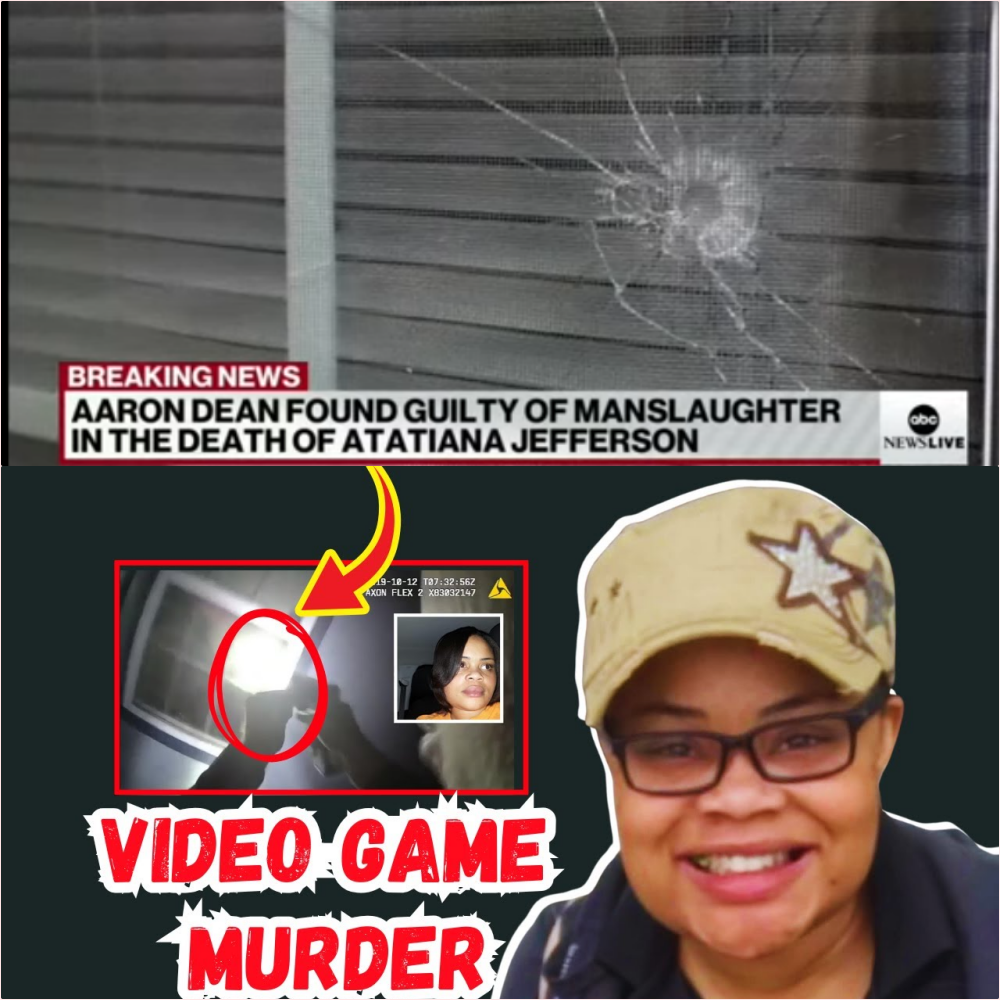

The story reached the news before the sun did. The summary was brutally simple: a 28-year-old Black woman, Atatiana Jefferson, shot and killed by a Fort Worth police officer through her own bedroom window during a welfare check. The words sounded impossible together, the way “open” and “empty” can contradict and still be true. Reporters learned the boy’s age, the family’s street, the timeline measured in minutes. Commentators reached for comparisons within the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex: Botham Jean in his own apartment a year earlier; a list that felt too long to say out loud.

But to understand how the night could bend into something so wrong, you have to know who she was before it did.

She was the daughter who came back because Yolanda Carr, her mother, needed help. The one with the Xavier University biology degree taped in a slim black frame, the one who stacked her MCAT materials in careful piles, penciled practice-test times into the margins of calendars, and daydreamed, not about prestige, but about work that mattered in exam rooms where the air smells like sanitizer and chapstick and hope. She worked odd shifts, took on extra hours, and learned the choreography of caregiving: pill organizers and doctor’s portals, pulse checks and coaxed appetites, the quiet heroics no one claps for because it would embarrass the person doing them.

She loved video games the way some people love trail runs or jazz standards—deeply, nerdily, with an insider’s grin. In that bedroom on East Allen, a headset dangled like a question mark; a tower hummed; a screen became a portal. She made joy a habit, not a luxury. That is what she offered her nephew on nights like this: an invitation to joy that was also an education—be precise, be persistent, be kind when someone else is learning.

She also loved the way Fort Worth looked when a thunderstorm walked the horizon. Backlit clouds. Pecans shivering. A sky that knows drama. The city is complicated and ordinary at once: stockyard bravado and church-parking-lot gentleness; barbecue smoke and biotech labs; Tarrant County courthouses and family reunions at parks with names nobody outside the neighborhood remembers.

The morning after, Fort Worth was loud. Not the polite sort of loud. It was voices through megaphones and into microphones, names chanted from courthouse steps. Body-camera footage, released quickly, showed what words alone might blur: the stealthy approach, the flash against glass, the command, the shot that came before any human could have processed what was happening, much less complied. You could feel a city flinch as it watched, some out of shock, some out of a bone-deep, centuries-old recognition. The distance between “protect” and “police” is supposed to be zero. On that night, it was a chasm.

Her father, Marquis Jefferson, faced cameras with a grief that made strangers feel like intruders. The family asked for what every family asks when the world tips: truth without varnish, accountability without delay. Aaron Dean, the officer who fired, was placed on administrative leave, resigned, then was arrested and charged. The charge—murder initially, later resulting in a manslaughter conviction—would become its own battleground of definitions and expectations, of what the law permits and what a community can bear. But in those early hours, the legalese felt like rain against a window you could not open. Inside the house, a nephew told investigators what he’d seen as plainly as children do. Outside, Fort Worth asked the question it always asks in moments like this: How do we live in the city we love when it does not love us back the same?

The answer that day did not come from podiums. It came from sidewalks. It came from neighbors who brought food because that is what you do when words fail. It came from church basements where someone’s auntie said a prayer that sounded like a lullaby and a verdict at the same time. It came from murals: her face on stucco, eyes forward, a halo not of gold but of sun-bleached Texas white. It came from students who tucked her name into speeches and study groups: an aspiring physician whose first oath was to family.

The case moved. Slowly at first, then slower. COVID-19 pushed everything into a fog of postponements. Tarrant County dockets stacked like unpaid bills. The family waited through years made of headlines that were not their own—other names, other cities, a country arguing with itself about what it wants to be when it grows up. In quieter moments, the waiting hardened into something useful: resolve. The boy grew taller. The house on East Allen changed in little ways the way houses do—paint freshened, a chair moved, a new plant in a chipped clay pot. Grief learned the floorplan and stopped bumping into the furniture.

When the trial finally began, the courtroom felt smaller than its square footage. Jurors watched the same clip everyone had watched and then watched it again with the volume of the world turned down. Experts diagrammed angles and timelines, drew arcs through the air to explain what a human brain can and cannot decide in two seconds. The defense pointed to a firearm inside the home, lawfully owned, and to fear. The prosecution pointed to a window, to no knock, no announcement, to the meaning of the word “welfare” when paired with “check.” The law is a machine; it loves its gears. But even the machine seemed to hesitate when it had to name what happened.

The verdict—manslaughter—arrived with the weight of “rare but not enough.” The sentence—11 years, 10 months, and 12 days—did what sentences always do: it drew a line and dared grief to fit inside it. Some called it accountability. Some called it a compromise with something that should never be compromised. All of them were right in the way people who hurt are often right at once, even when they disagree.

What remained truer than the verdict was the story of a life that should have stretched over decades. The word doctor was supposed to belong to her one day, not because of prestige but because she wanted to be the kind of person who sat on the bad days with other people and turned them into manageable days. The word aunt belonged to her already, and it shone. The words Fort Worth belong to her too—city of her house, her porch bulb, her last night’s laughter. The zip code, the county, the state—they are not just coordinates. They are context, the United States as it is, not as it promises.

In the years since, the city has tried, in fits and starts, to learn. Policy memos were drafted, trainings scripted, welfare-check protocols rewritten to say out loud what should have been obvious all along: when you are sent to ensure life, you announce yourself. You knock. You slow down enough to tell the difference between a crime and a family. Some of those memos gathered dust. Others made it into roll-call binders where officers scribbled initials to prove they’d read them. Meanwhile, murals never gathered dust. Paint clings better to memory than to bureaucracy.

On East Allen Avenue, the evenings are still the same color at dusk. Porch lights still throw small, brave circles on cracked driveways. On certain nights, when a storm shoulders up to the city limits, the air tastes like tin. A neighbor might glance across the street and feel, for a second, the urge to do what James Smith did—to check, to care, to call, to believe that help is the opposite of harm. That faith is a civic muscle. It should not ache when you use it.

If you listen, you can hear the echo of a controller tapping out a rhythm learned from an aunt who taught a boy that precision and patience win more battles than panic. You can hear her voice in that rhythm. It does not ask for pity. It asks for practice—of better policy, better habits, better instincts, the kind that make the word “welfare” mean what it says.

Because the first sentence of that night is still the clearest truth: a house was bright, a child was laughing, and a woman with a future stood up to see about her family. That should have been the whole story. It will never be. But in Fort Worth, Texas, people carry the original ending in their pockets anyway, like a photograph—creased, handled, beloved—and take it out when they need to remember what justice is supposed to protect.

And when the sky breaks open over Tarrant County and the rain lifts the day’s heat, it is almost possible to believe the city can learn to hold that truth without dropping it. Almost.

The night in Fort Worth, Texas, was the kind that pressed against windows—thick, restless, alive with the hum of distant traffic and the whisper of warm air through pecan leaves. Inside a small, single-story house on East Allen Avenue, a blue glow flickered from a bedroom window. The sound of laughter—quick, bright, like a match struck in the dark—cut through the quiet. On the other side of that laughter sat Atatiana “Tay” Jefferson, 28 years old, her hair pulled back, controller in hand, locked in a video game battle with her 8-year-old nephew. It was past midnight, but the house still pulsed with energy. She leaned forward, teasing, her competitive grin soft but determined. “You sure you can beat me, little man?” she said. He giggled, thumb jamming the buttons, eyes wide in concentration.

In that small bedroom, the world was simple—joy, family, and the hum of a television. The rest of the city might as well have been a thousand miles away. The night, the laughter, the life inside that home—they were all ordinary. But within minutes, everything would fracture.

Atatiana had built her life on purpose and care. She had come back home to Fort Worth to look after her mother, Yolanda Carr, whose health had begun to fade. She didn’t hesitate, not once. She packed her things, left her job, and moved back into the family house—the same one she’d grown up in, the same one filled with photos, hand-me-down furniture, and the warmth of years. Her days were busy and full: caring for her mother, working shifts to pay bills, and studying late into the night for the MCAT, the exam that stood between her and medical school.

Her dream wasn’t small—it was deliberate. She wanted to heal people, to make something out of her degree from Xavier University, to turn knowledge into service. Her textbooks were always open, highlighters scattered like confetti. But the grind never took away her spark. She was the kind of woman who could move between science and laughter without missing a beat.

When she wasn’t studying, she was gaming. Video games were her sanctuary. To some, they were a hobby; to her, they were therapy, escape, connection. The hum of her console, the click of buttons, the fast rhythm of digital life—it was where she could be free of expectation. Her nephew loved it, too. Every time he visited, they played until their eyes grew heavy and the world outside blurred into the comfort of shared joy.

That Friday night—October 11, 2019—was no different. She had helped her mother through the day, cooked dinner, cleaned up, and tucked her into bed. Then she turned to the one space that was truly her own. The house smelled faintly of detergent and fried food, the scent of a lived-in home. The boy sat cross-legged on the carpet beside her. The room buzzed with life, laughter, and love.

Across the street, however, another scene was unfolding. James Smith, their neighbor, stood by his window, frowning slightly. He’d lived there for years, knew the Jeffersons by sight and by wave. That night, something caught his attention—the front doors of the Jefferson house were open, and the lights inside were still on. It was nearly 2:30 a.m., late for anyone, especially for a family home.

Smith hesitated. Maybe someone forgot to close the door. Maybe they’d fallen asleep watching TV. But what if something was wrong? What if someone had broken in? In his gut, the kind of worry only a neighbor could feel took root. He didn’t want to intrude, didn’t want to alarm anyone, but he also couldn’t ignore the sight. Finally, he picked up his phone and called the Fort Worth Police Department’s non-emergency line.

“Hi, I just wanted to request a wellness check,” he told the dispatcher. “The doors are open over there. Lights are on. I’m just making sure everyone’s okay.”

He hung up, exhaled, and watched the house from across the street. Inside, the light still glowed soft and steady. He could see shadows moving—maybe them, maybe not. He told himself it would be fine. It was just a check, nothing more.

Inside the Jefferson home, Atatiana and her nephew were still lost in their game. Their laughter carried down the hallway, bouncing off the walls. The night air was calm. The world was safe. Or at least, it was supposed to be.

Across Fort Worth, two police officers received the call. It came through their radio: open structure—possible burglary. The words were routine, clinical, detached. But they carried weight. The kind of weight that turns a quiet street into a stage for something irreversible.

When Officer Aaron Dean, 34 years old, pulled up near East Allen Avenue, he didn’t park in front of the house. He didn’t turn on his sirens or lights. He didn’t walk to the door. Instead, he and his partner, Officer Carol Darch, approached in the dark, flashlights cutting through the night. The house loomed quiet, its open doors glowing like unblinking eyes. The air was still, the crickets silent.

Inside, Tay was laughing. Outside, Dean was circling her house like a ghost.

They crept through the yard, flashlights slicing through the trees, boots soft against the grass. They didn’t announce themselves. They didn’t knock. They didn’t call out to say, “Fort Worth Police.” Instead, they treated the home like a threat. Their radios hissed, their breath steady and quick.

From her window, Atatiana saw the movement. Just a flicker—light bouncing where it shouldn’t be. Her laughter stopped. Her heart ticked once, then twice, harder each time. She leaned toward the blinds, frowning. Who would be outside at this hour?

“Stay here,” she whispered to her nephew.

He nodded, clutching the controller. The room felt smaller suddenly, the hum of the television swallowed by silence.

She stepped closer to the window, careful, curious, unafraid but alert.

Outside, Officer Dean’s flashlight beam landed directly on her window. The reflection flashed white.

He shouted—sharp, commanding, sudden:

“Put your hands up! Show me your hands!”

Two seconds. That’s all. Two seconds between command and action.

Then—a single gunshot.

The sound tore through the stillness, through the home, through the heart of a city that would never forget it.

Inside, her nephew froze. The controller hit the floor. His aunt fell beside it.

Across the street, James Smith’s phone slipped from his hand. He’d called for help. What he got was tragedy.

The red and blue lights came next, sirens flooding East Allen Avenue, washing over houses that had never seen this kind of chaos. Neighbors spilled onto porches, drawn by instinct and fear. The air was heavy with disbelief.

What happened inside that house was over in seconds. But the echoes would last years.

Her name, her story, her voice—it would ripple across Fort Worth, across Texas, across the United States. Because what began as a simple call for safety had ended with a bullet through a window, and a family—an entire community—left to wonder how something so ordinary could turn so devastating, so fast.

In that small house on East Allen Avenue, a bright future was silenced.

And across America, the question began to rise again—one too familiar, too painful, too necessary to ignore.

But that’s not where the story ends. It’s where everything begins.

The sirens didn’t stop for hours. Their echo crawled through East Allen Avenue, bounced off the brick walls and wooden porches, and finally dissolved into the dawn. The neighborhood—so quiet most nights you could hear the cicadas hum—was now alive with chaos. Police lights flashed against the windows of sleeping houses, painting the street red and blue, red and blue, until the rhythm of emergency became the new heartbeat of Fort Worth’s south side.

Inside 1204 East Allen Avenue, the home that had always been filled with laughter and warmth now felt foreign, colder somehow. The same space where Atatiana Jefferson once studied medicine, cooked dinner for her mother, and played video games with her nephew had turned into a crime scene. Plastic evidence markers lined the carpet. Cameras clicked. Officers moved through the hallway with the stiffness of people who already knew something irreversible had happened.

The boy—her nephew, only eight years old—stood frozen, the world around him spinning too fast to understand. His small hands trembled, the echo of the gunshot still burning in his ears. He had seen his aunt—his best friend—fall to the ground. He had watched her body go still. He didn’t know why the man outside had shot. He didn’t know that the flashlight and the badge belonged to someone who was supposed to protect them.

He only knew that she wasn’t moving.

Across the street, James Smith, the neighbor who had called the police, was pacing on his porch, his phone still in hand. He could see the chaos unfolding, officers swarming the yard he’d looked at for years. The same yard where he had once seen Atatiana mowing the lawn, laughing as her nephew chased after her with a toy plane. He had called to help. That word—help—now felt heavy, poisonous. “I called them to check on her,” he whispered to a reporter later. “I didn’t call them to shoot her.”

Word traveled fast in Fort Worth. Before the sun even rose, the news spread across Tarrant County, then across Texas, then across the country. A young woman had been shot and killed in her own home during a welfare check. The story was too familiar and too unthinkable at once. People whispered the same question again and again: How?

By morning, East Allen Avenue was filled with cameras, reporters, and sorrow. A woman from down the block brought flowers and set them near the front steps. A group of teens who lived nearby stood silently, staring at the yellow tape. Cars slowed down as they passed, drivers shaking their heads. And inside that house, the boy was taken away—safe, but changed forever.

When the sun rose over Fort Worth, it wasn’t kind. The light that spilled across the Jefferson home felt intrusive, harsh, revealing too much. The Fort Worth Police Department held a press briefing before noon. The spokesperson’s words came out clipped, practiced, detached. They spoke of “tragic circumstances,” of “ongoing investigation,” of “standard procedures.” But for the people standing outside that press conference—neighbors, friends, strangers who had come just to bear witness—it didn’t sound like an explanation. It sounded like another excuse.

Because the body camera footage had already begun to circulate.

It showed the officers arriving in silence. No sirens. No knocking. No announcement. Aaron Dean’s flashlight cutting through the backyard. The command shouted through glass—“Put your hands up! Show me your hands!”—and then the shot. Two seconds. That’s all it took. Two seconds to take a life, two seconds to change a city.

People didn’t need reporters to tell them what they saw. It was right there. No warning. No chance. No mercy.

That same afternoon, protests began to form downtown. Dozens, then hundreds of people gathered outside Fort Worth Police Headquarters. They held signs with her face—her graduation photo, her smile bright and fearless. “Justice for Atatiana Jefferson,” they chanted. “Say her name.”

In the crowd were parents, students, church leaders, and people who had never met her but felt as if they had. The air pulsed with anger, but underneath the fury was grief—grief so deep it was almost holy. Fort Worth had seen tragedy before, but this one felt raw in a different way. It wasn’t just a woman killed. It was a daughter, a caretaker, a scientist, a dreamer, shot through her own bedroom window in the place she was supposed to be safest.

Atatiana’s family could barely speak when they appeared before the cameras. Her father, Marquis Jefferson, stood trembling, his voice cracking beneath the weight of disbelief. “My daughter was taken from me,” he said, eyes wet. “She was everything to me. She had her whole life ahead of her.”

Her sister, Ashley Carr, wiped tears and whispered that Atatiana had always been the one who stepped in when things fell apart. “She took care of all of us,” she said. “She was the glue.”

And her nephew—the boy who saw everything—was now silent, withdrawn, trying to piece together a world that no longer made sense.

The following days blurred together. The house was cleaned, but not of memory. The flowers on the porch wilted under the Texas heat. People left cards, candles, handwritten notes that read We love you, Tay and You deserved better.

Meanwhile, pressure mounted on the Fort Worth Police Department. The city’s mayor called for transparency. Civil rights groups demanded action. Social media erupted, comparing her death to that of Botham Jean, another Black Texan shot in his own home by an officer who mistook his apartment for hers just a year before in Dallas. The similarities were unbearable.

Within 48 hours, the tension reached its breaking point. On October 14, 2019, Officer Aaron Dean resigned from the department. Hours later, he was arrested and charged with murder.

But even as headlines declared “Justice in Motion,” the city’s heart remained restless. Fort Worth had seen this before—arrests, promises, apologies—and it had learned not to trust the language of bureaucracy. The people didn’t want statements; they wanted change. They wanted to believe that a wellness check couldn’t end with a gunshot.

That night, as the crowds gathered again, the air was thick with emotion. Someone read a poem about Atatiana under the courthouse lights. Someone else played soft gospel on a portable speaker. There was anger, yes—but also something else. A quiet determination.

Because Atatiana Jefferson was more than a name in a headline. She was a daughter who came home to take care of her mother. A woman who studied late into the night for medical school. A gamer who laughed too loudly, who loved too deeply, who lived too brightly.

And Fort Worth—America itself—was being forced to look in the mirror again. To see her face, her story, her humanity. To confront what it means when safety is not guaranteed, even inside your own home.

As the night deepened and candles flickered along East Allen Avenue, the neighborhood fell quiet again. But it wasn’t the same quiet as before. It was heavier now, filled with questions that wouldn’t fade.

Because in that silence, you could still almost hear it—the echo of her laughter, the click of a controller, the soft voice of a woman who only wanted to live her life in peace.

The days after October 12, 2019, moved like molasses through Fort Worth. Time didn’t just pass—it dragged, heavy with disbelief, anger, and the echo of a single gunshot that refused to fade. The sun still rose over East Allen Avenue, but it felt colder now, as though light itself had learned to hesitate before entering that house.

Inside, silence had a shape. It stretched across the rooms that once sang with laughter, lingered over the walls where family photos hung—a graduation cap tilted slightly askew, a mother and daughter cheek to cheek, a little boy mid-laugh, blurry from motion. The Jefferson home had always been a place of life, but now even the air inside carried grief like dust—fine, invisible, but impossible to ignore.

Atatiana’s mother, Yolanda Carr, moved like a shadow through her own home. Her illness had already weakened her, but this loss hollowed her completely. Every room whispered her daughter’s name. The scent of her lotion still clung to the towels. Her notebooks lay open on the table, half-filled with notes about cell structure, chemical bonds, and life plans that would never be completed. There were mornings Yolanda would wake up believing she’d heard Tay in the kitchen, making breakfast. But when she rose, the house answered only with silence.

Her sister, Ashley Carr, tried to be strong for everyone else. She spent her days juggling phone calls from reporters, lawyers, and community leaders. Everyone wanted to talk about justice. But what she wanted—what she really wanted—was her sister back. She wanted the sound of her voice, her jokes, the warmth of her presence. She wanted to hear her say, “We’ll be fine,” the way she always did. But the words that had once anchored her were gone, replaced by statements and case numbers.

Outside, Fort Worth was buzzing. The shooting had sparked outrage far beyond Texas. Across the country, people were talking—online, on the news, in coffee shops, at protests. Hashtags carried her name: #AtatianaJefferson, another name added to a list that no one wanted to keep writing.

Protesters flooded the streets of Downtown Fort Worth, their voices echoing against glass office towers and courthouse steps. They carried signs that read “Justice for Atatiana”, “Say Her Name,” and “We Deserve to Live.” They weren’t just angry—they were exhausted. It wasn’t the first time. It wasn’t even the second. From Ferguson to Baltimore, from Dallas to Minneapolis, the cycle had become all too familiar: a Black person dead, a police officer on leave, a press conference of regrets, and a community left to bury its dead while waiting for justice that never came easy.

Still, something about Atatiana’s case cut deeper. She hadn’t been walking down a street. She hadn’t been driving. She was at home. Her home. A sanctuary turned into a target. It was the kind of violation that rippled through every Black household in America. People whispered it to themselves as they locked their doors at night: If it could happen to her, it could happen to us.

In Fort Worth, that fear sat heavy. The city was divided between grief and fury. On one side, people who wanted to believe it was an accident. On the other, those who were done with believing. “How many accidents do we survive?” one protester shouted outside police headquarters. “How many more lives before they learn to knock?”

The body camera footage, played again and again on news stations, became unbearable. There was no mystery left to debate—only a reality to face. You could hear the officer’s voice, sharp and sudden, then the shot. No time for breath, no time for compliance. Just light, command, death.

The department moved quickly, but for many, not quickly enough. Aaron Dean, the officer who fired the shot, resigned two days after the killing. The same day, he was arrested and charged with murder. To some, it was accountability. To others, it was theater. Because charges are not the same as conviction, and the people of Fort Worth had seen too many headlines fade to dust.

The mayor made a statement calling it a tragedy. The police chief apologized, his words measured, professional, hollow. “We failed her,” he said. But the crowd outside didn’t want apologies. They wanted change.

Meanwhile, inside the Jefferson home, the family tried to survive each day without her. The nephew—the only witness inside that bedroom—had stopped sleeping through the night. He told investigators that his aunt had been protecting him, not threatening anyone. He remembered her telling him to stay still, to stay quiet, to stay safe. Those words haunted him like a broken lullaby.

Her father, Marquis Jefferson, became a fixture in front of cameras. He wasn’t an activist before, but grief made him one. His eyes, swollen from sleepless nights, burned with the need for truth. “My daughter wasn’t a suspect,” he said into microphones. “She was a citizen in her own home.” His voice trembled, but his anger was steady, grounded in the impossible clarity of loss.

For the next few weeks, Fort Worth lived in a state of suspended emotion—rage without relief, grief without peace. Candlelight vigils were held outside her home, each one drawing larger crowds. Pastors led prayers, mothers held their children tighter, and the street outside 1204 East Allen Avenue became something sacred—a memorial, a warning, a symbol.

In the weeks that followed, people began to learn more about who Atatiana was. Stories poured out—how she’d spent her college years volunteering at community clinics, how she’d helped classmates who couldn’t afford lab supplies, how she’d never missed a single birthday for her nieces and nephews. Her students from tutoring sessions described her as patient, brilliant, and endlessly kind.

Her friends talked about her gaming. They laughed through tears recalling her trash talk during late-night matches, her contagious laugh, her sharp mind. “She could turn anything into a competition,” one friend said. “Even kindness.”

Her sister Ashley once said, “Atatiana had this way of making you feel seen. Even when you didn’t want to talk, she’d just look at you until you did.”

But as the family mourned, the machine of the legal system began to move. Investigations. Statements. Hearings. Words like “justifiable force”, “protocol,” and “reasonable fear” began to fill the space where human words should have been. The narrative, once so simple—a young woman shot in her home—became tangled in paperwork and defense strategies.

The officer’s lawyers claimed he believed there was a burglary in progress. They said he thought he saw a gun. They said he feared for his life.

But those words—“feared for his life”—fell like acid on open wounds.

Because Atatiana Jefferson had also feared for hers.

Only one person in that house had a reason to be afraid. Only one person had no chance to understand, no voice to answer, no chance to live.

In the months that followed, national attention only grew. Fort Worth found itself under a microscope. The city’s police department, already criticized for racial disparities and use-of-force incidents, faced renewed scrutiny. Old cases resurfaced. Community leaders met with city officials. Some hoped for reform. Others expected disappointment.

Through it all, the family stayed united. They were determined that Tay’s name would not fade. They started the Atatiana Project, a foundation aimed at supporting students of color in STEM fields, continuing the dreams she left unfinished. Her memory became fuel—not just for mourning, but for movement.

And yet, grief is never linear. It loops. It ambushes. It arrives on quiet mornings when the world seems normal again and shatters that illusion with a scent, a sound, a memory.

For the Jeffersons, normal no longer existed.

The day her father broke down during an interview—his voice cracking as he whispered, “She was my baby”—the world saw the real cost of that night. Not statistics. Not politics. Just love, interrupted.

By winter, the street where she had lived became a pilgrimage site. Journalists came, photographers came, people left candles that melted into wax puddles on the sidewalk. Her story joined a national narrative she never asked to be part of.

Atatiana Jefferson became both a name and a question—what does safety mean if home is not safe? What does justice mean when it always arrives too late?

The investigation rolled on. The trial loomed in the distance. And somewhere in that house, between the smell of old textbooks and the flicker of game consoles long unplugged, her spirit lingered—a reminder of what was lost, and of what America still refuses to learn.

Her laughter, they said, used to light up the block.

Now, it haunted the city.

The spring after her death came late that year, as if Fort Worth itself didn’t know how to move forward. The air was heavy with the residue of winter, thick and restless. Flowers tried to bloom along the sidewalks of East Allen Avenue, but the street still carried a stillness that felt unnatural. The house at 1204 stood there unchanged—same chipped paint, same porch light—but it no longer felt like home. It had become a landmark of grief.

Inside, the Jefferson family moved through each day as though wading through water. Grief had turned time into something elastic—hours stretched and folded, days vanished without notice. The calls from reporters slowed, the news trucks disappeared, and yet the silence that replaced them was worse. For weeks, Ashley Carr sat at her sister’s old desk, staring at her open notebooks, still marked with highlighter and handwritten notes. The words seemed frozen in time—“Study session: enzymes, cell respiration, equilibrium”—the dreams of a woman who had been planning a life, not an ending.

Their mother, Yolanda Carr, weakened more with each passing week. Her illness had taken a toll even before that October night, but losing her daughter fractured something deeper. Friends came by with casseroles and condolences, but she barely spoke. She would sit in her favorite armchair by the window, staring at the porch where Atatiana used to water the plants, her voice soft with laughter. Sometimes she’d whisper, “I can still hear her,” and no one had the heart to correct her.

The little boy—Atatiana’s nephew, now quiet where he had once been playful—refused to sleep in his own room. He told his mother he was afraid of the dark, afraid of windows. He said the light outside sometimes flickered, and every flicker felt like a shadow moving. His family didn’t know how to tell him that shadows sometimes wore uniforms.

Meanwhile, the case continued to crawl forward. Aaron Dean had been charged with murder, but the gears of justice turned slowly. Each hearing felt like reopening a wound. The defense painted him as a man who made a mistake. They said he had feared for his safety. They said it wasn’t intentional. But the community remembered the video, the speed of it, the silence before the shot. They remembered how she hadn’t even had time to speak.

Public trust in the Fort Worth Police Department had already been fragile. Now it splintered. Protests swelled outside city hall, then faded, then returned again. The signs were the same, the chants familiar: “No knock, no knock, justice doesn’t stop.” The faces of strangers became familiar in the fight for her name. Activists like Opal Lee, the grandmother of Juneteenth, joined the marches, her voice trembling but firm. “We’ve come too far,” she said, “to still be dying in our homes.”

Her words hung in the air like scripture.

For the Jefferson family, these protests were both a balm and a burden. They were grateful for the love, but it also meant reliving the moment again and again—each chant a reminder of the shot that shattered everything. Ashley often said that grief had a strange rhythm. Some days, it was quiet, almost bearable. Then it would come roaring back without warning, triggered by something small—a smell, a song, a memory.

Her father, Marquis Jefferson, carried his grief differently. He wore it like armor. He attended rallies, spoke at events, and met with local officials, demanding transparency, demanding reform. He said he wouldn’t rest until his daughter’s name was cleared of every false narrative, until every person in America knew what had been taken from her. But beneath the strength, he was unraveling. His health declined, his heart heavy not just with sorrow, but with the weight of a country that seemed unwilling to change.

In November 2020, a little more than a year after his daughter’s death, Marquis Jefferson passed away. The news broke quietly at first, then rippled outward—a second tragedy in a family that had already endured too much. He never lived to see justice done. When Ashley spoke at his memorial, her voice cracked. “He died waiting for something that should’ve been simple,” she said. “Accountability.”

As months bled into years, the legal process became a cruel kind of purgatory. The COVID-19 pandemic swept through the world, and with it came more delays. Court dates were postponed, evidence reviewed, witnesses rescheduled. For the Jeffersons, every delay felt like a betrayal—a system that could move quickly enough to take a life but never fast enough to honor it.

And yet, the world hadn’t forgotten. Murals of Atatiana began appearing across Texas—in Dallas, in Houston, in Fort Worth itself. Her face, painted in bold colors, became a symbol. Her eyes, bright and determined, stared out from brick walls, as if still demanding answers. Local artists gathered on weekends to touch up the murals, adding phrases like “She Was Studying to Heal” and “Her Life Mattered.”

Her name joined others across the nation: Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Botham Jean, Sandra Bland. Different cities, same heartbreak. A pattern too familiar to ignore.

When the protests of 2020 erupted across the United States, thousands of people in Fort Worth carried signs with her name. “Say her name!” they shouted in the rain. “Say her name!” The crowd stretched for blocks, a sea of umbrellas and tears. Her story became part of a larger tapestry of voices demanding not just justice for one woman, but for all the lives cut short under the same shadow.

And still, inside that small house on East Allen Avenue, time stood still. The front door had been repainted, the flowers replanted, but inside, everything was as she left it—the books stacked neatly, the game console unplugged, the photo of her and her mother smiling on the dresser.

Her nephew would sometimes sneak into her room and sit there quietly, the way children do when they don’t have the words for loss. He’d look at her controller, her notebooks, the faint indentation of her hand on her desk. When asked what he was doing, he’d simply say, “I’m waiting for her to come back.”

But grief doesn’t reverse itself. It doesn’t bargain. It only teaches you how to live differently.

By the time 2022 arrived, nearly three years after that night, the trial of Aaron Dean was finally set to begin. The news made headlines again, reopening wounds that had only just begun to scar. Ashley Carr stood outside the courthouse before the first day of testimony. Cameras flashed around her, but she didn’t flinch. She held her sister’s photo close to her chest and whispered, “This is for you, Tay.”

Inside the courtroom, the air was thick with tension. The jury sat stiff, eyes fixed on the screen as body camera footage played once more. The sound of the officer’s voice echoed through the room. “Put your hands up! Show me your hands!” Then the shot. The silence after it felt infinite.

Prosecutors argued that Dean had acted recklessly, that he never identified himself, that he had fired without cause. The defense insisted he saw a gun, that he feared for his life. But the evidence told another story: the gun inside the home had never been raised, never even pointed. It was legally owned, tucked away in a space where it belonged—inside a home that was supposed to be safe.

The trial stretched for weeks, each testimony reopening old pain. The most difficult moment came when Atatiana’s nephew, now older, took the stand. His voice was quiet, steady, heartbreakingly calm. He described that night: the sound of movement outside, the light through the blinds, the flash, the noise. “She was just trying to see who was out there,” he said. “She didn’t even have time to be scared.”

You could hear people in the courtroom crying quietly. Even the air seemed to mourn.

When the verdict finally came on December 15, 2022, it was not the ending anyone had imagined, but it was something. Aaron Dean was found guilty of manslaughter—not murder, but a conviction nonetheless. A week later, he was sentenced to 11 years, 10 months, and 12 days in prison.

For some, it was relief. For others, it was another insult dressed as justice. But for the Jefferson family, it was simply the end of one part of the story.

Outside the courthouse, Ashley spoke softly to the crowd gathered around her. “We know justice was served,” she said. “But it doesn’t bring my sister back. It doesn’t erase the pain.”

Her words floated through the air, soft but heavy. The crowd stood in silence.

As the sun set that evening over Fort Worth, the murals of Atatiana caught the fading light. Her eyes seemed to glow, her smile frozen between memory and defiance. Across the city, candles were lit once more.

For some, it was remembrance. For others, resistance. But for everyone who spoke her name, it was a promise—that she would not be forgotten.

Because Atatiana Jefferson wasn’t just a tragedy.

She was a warning.

She was a mirror.

She was a heartbeat that refused to fade, still echoing through Texas air.

And if you stand quietly enough on East Allen Avenue tonight, you might still hear her—somewhere between memory and justice—her laughter floating through the wind, reminding the world of the life that was taken, and the love that will not die.

The winter after the verdict fell over Fort Worth like a long exhale—one that hurt on the way out. The trial was over, the cameras were gone, and yet the city couldn’t shake the weight of what had happened. The courtroom had given its sentence, but grief isn’t bound by verdicts. It doesn’t obey calendars or news cycles. It lingers—in faces, in streets, in the quiet moments when everything should have gone back to normal, but nothing truly had.

Ashley Carr stood on the porch of the family home one cold January morning, looking out at East Allen Avenue. The paint on the steps had begun to peel. The flowers in the pots were long dead from the frost. She wrapped her coat tighter and exhaled, watching her breath rise into the gray air. Somewhere deep in that house, her mother was still asleep, wrapped in silence and memories. The nephew—no longer the same child he had been three years ago—was getting ready for school, moving slower than most mornings. He didn’t like leaving the house anymore. He said he didn’t trust the world outside.

Every part of that home carried her sister’s ghost—not the frightening kind, but the kind that lived in ordinary things. The dent in the sofa cushion where she used to sit. The worn pages of her biology textbook. The mug with faded lettering that read Future Doctor. Ashley sometimes touched it, just to remind herself it was real.

The news said Aaron Dean had been sentenced to eleven years, ten months, and twelve days. The precision of it almost felt cruel, as though justice had to be measured down to the second. Some called it a victory. Others called it mercy disguised as punishment. Ashley called it unfinished business. “He gets to live,” she told a reporter once, her voice calm but brittle. “My sister doesn’t.”

Across Fort Worth, murals of Atatiana Jefferson had begun to fade from the brick walls, the paint peeling under the Texas sun. But even faded, they were unmistakable—her face, caught in a half-smile, still watching over the city that had failed her. Activists came by on weekends with buckets of paint to touch up the colors, to make sure her eyes stayed bright, her name still legible. Because memory, like justice, requires maintenance.

Her story had become something larger than any one person. Students at Texas Christian University organized scholarship drives in her name. A group of local doctors started a mentorship program for young Black women in science, calling it The Jefferson Initiative. Even as time moved forward, her name found new life—not in tragedy, but in purpose.

Yet inside her family, the wounds never closed. Her mother, Yolanda, passed away not long after the trial. Her body, already fragile from illness, seemed to surrender after years of carrying too much sorrow. When Ashley buried her, she whispered, “You’re with her now, Mama,” though the words cut deep.

There were moments when the house felt completely empty, as if grief had hollowed it out. And yet, sometimes, Ashley swore she could feel both of them—her mother and her sister—still there. Not haunting her, but watching, urging her forward.

She decided to turn the house into something new.

With the help of neighbors and community volunteers, Ashley began converting the old Jefferson home into a community space—a hub for mentorship, education, and healing. The idea was simple: to turn the place of her sister’s death into a place of life again. She called it “The Light House.” Because even in the darkest nights, Atatiana had been light.

The first event held there was quiet—just a few kids, a few parents, and some local teachers who came to read, to talk about science and dreams. Ashley stood by the doorway, watching a group of children huddle around a microscope, their eyes wide with curiosity. One of them—a little girl in a pink hoodie—looked up and said, “Miss Ashley, can I be a doctor like Miss Tay?”

Ashley’s throat tightened. “You already can,” she said softly. “You already are.”

That night, after everyone had gone, she sat alone in the same room where her sister had once played video games with her nephew. The window was repaired, but every time the wind rattled it, she felt her heart skip. She reached over to turn off the lamp, but before she did, she noticed something—the soft reflection of light against the glass, faint but steady, like a pulse.

Fort Worth had changed since that October night, but not enough. The city passed new training policies, new reforms for how wellness checks were handled. Officers were required to announce themselves more clearly, to de-escalate before they engaged. Yet the people still whispered about what it all meant—whether reform could fix fear, whether policy could heal mistrust.

On the third anniversary of her sister’s death, the Jefferson family gathered outside the house. The street was lined with candles, glowing soft and gold in the night air. The smell of wax mixed with the faint scent of honeysuckle from the fence. Neighbors came with flowers. A pastor read a prayer.

Ashley spoke last. Her voice was steady, the kind of strength that comes from surviving what should have broken you. “We don’t light these candles because we’ve moved on,” she said. “We light them because we’re still here.”

The crowd murmured “Amen.”

The little boy—no longer eight, now almost twelve—stepped forward and placed a single white rose at the foot of the steps. Then he looked up at the sky. “She can see us,” he said.

And for a moment, it felt true. The wind shifted, soft and warm. Somewhere down the street, the faint hum of cicadas rose, echoing like it had before that night, when everything was still whole.

The mural on the corner of East Allen and Collier reflected the candlelight, and her face seemed alive again, painted in bold strokes—Atatiana Jefferson, smiling with the same quiet determination she’d carried all her life.

Her story was no longer just about loss. It was about what remained—the love that outlasts the pain, the courage that survives the silence.

Because justice, real justice, isn’t just a sentence.

It’s a legacy.

It’s a promise whispered into the Texas night:

We will not forget.

And if you drive down East Allen Avenue today, you’ll still see the porch light on—always on.

Not because someone forgot to turn it off.

But because some lights are never meant to go out.