Omaha, Nebraska, USA—beneath a stand of lilacs in a quiet American backyard, a bracelet caught the light. It was nothing, really—just a small glimmer in the dirt—until you realized the wrist was still wearing it. Decades later and half a world away in Australia, a sterile cotton swab collecting a son’s DNA would tug on that same thread, yanking the past through airports and aliases, across oceans and time zones, straight back to the night a high-school saxophonist took the car keys the hard way and went to the drive-in as if ordinary life hadn’t just been shattered. This is the long American story of a boy from Omaha who learned to hide in plain sight, the U.S. Marshals who refused to forget, and a set of genes that kept their secrets only until someone asked the right question.

He was born William Leslie Arnold on August 28, 1942, in Omaha, the kind of Midwest city where fall football games folded into church on Sundays and the cornfields beyond the subdivisions looked endless when you were sixteen. In 1958, America’s heartbeat was neon and chrome: burgers at the counter, summer lawns clipped neat as a crew cut, and the glow of a drive-in movie screen making a silver rectangle of the night. If you were a teenager then, the theater was a rite of passage. You steered your dad’s car into a spot, clipped the speaker to the window, and watched the show with friends, the radio humming, the future feeling like it would arrive right on schedule. Leslie—a band kid with Elvis hair and the self-conscious polish of a good student—wanted that night at the local drive-in the way a thirsty man wants water. The program was a double feature: No Time for Sergeants and The Undead. It wasn’t the films that mattered. It was the independence. It was being seen. It was finally not feeling like a child in a house where being a child seemed to mean never passing inspection.

Omaha sits far from the coasts, but the country’s weather—political, social, private—rolls across the plains all the same. In the Arnold house, the weather lived in the mother’s voice, which could switch from ordinary to iron in a heartbeat. She wanted the grass shaved evenly. She wanted the bed corners sharp. She wanted the boy to wear his belt and watch his tone. He wanted music. He wanted to be allowed to like the girl his mother dismissed as wrong for him. Families come apart in louder ways, it’s true—screaming and plates and doors ripped off hinges—but this was a slow struggle of rules and resistance, a set of collisions across years that felt to a tightly wound teenage boy like always walking on black ice.

The night of September 27, 1958, is the hinge of everything. It is the line that divides the boy who could have worked summer shifts and saved for a jalopy from the man who would someday wear a name that wasn’t his. The house was ordinary—dining room, kitchen, a living room with the furniture that families of the Midwest bought because everyone else did. The argument was ordinary too, until suddenly it wasn’t. A Remington .22 kept in a closet, a decision that kicked the rest of his life into motion, a moment when a teenager with a temper like stacked kindling lit the match. There’s nothing to gain from graphic detail; what matters is that two people who should have lived ended up gone, and a sixteen-year-old, still a kid in school with a saxophone case and a prom in his future, walked out into the cool Nebraska evening and continued to behave like he had only been told “be home by eleven.” He went to the movies with his girlfriend. He came home. He returned to chores and school and church. He even went to his father’s business at opening time and asked an employee to keep an eye on it, as if good habits could paste over catastrophe. When neighbors asked where the parents had gone, he offered an explanation that felt just plausible enough to be waved through: a trip out west, chasing a confused grandfather who’d stepped off a train and wandered. People wanted to believe.

But neighborhoods are a web. Threads tug. A grandmother’s quiet comments don’t match a neighbor’s memory of schedules and phone calls. Police are called. The backyard that had seemed tidy now looks like a question. Officers turn soil beneath the lilacs. A cuffed hand points. A bracelet glints. And suddenly Omaha—wholesome, middle America Omaha—has a crime that whispers to the whole country. There’s a reason true-crime readers nod immediately when they see a place like Nebraska on a map: the contrast is too strong. The “it can’t happen here” only makes the “it did happen here” echo longer.

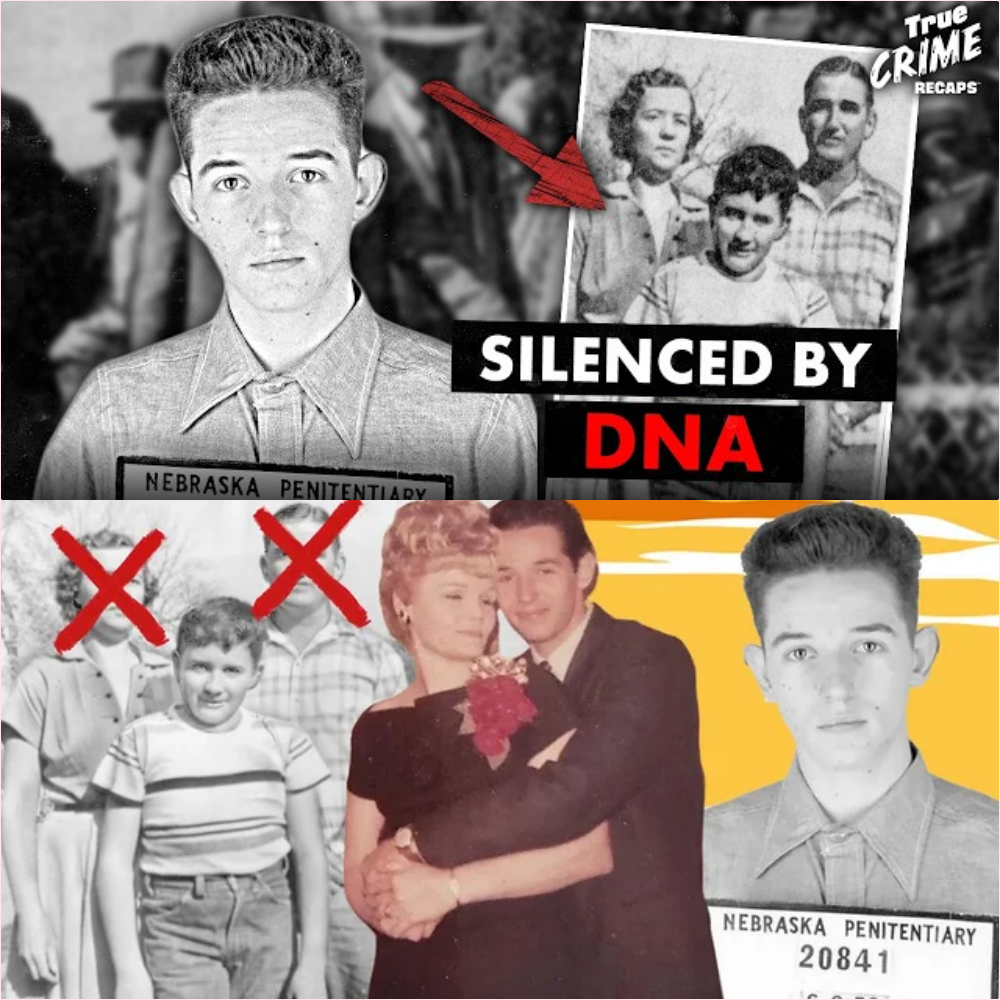

In the interrogation room and in the papers, the story became a courtroom outline: first-degree murder based on premeditation, later bargained down to two counts of second-degree to secure a plea. June 2, 1959, is the date the state recorded a life sentence for a boy not yet seventeen. He wore his hair slicked back like Elvis; he played the sax; he had only small infractions to his name in school—once he forgot a belt. But testimony can turn a report card into a warning label. “Smart, but troubled,” someone said. A psychiatrist searched for an image and found one: a smoldering volcano. You can imagine the prosecutors reading the phrase and circling it in their notes. You can imagine the kid hearing it and wanting to smash something delicate and silent because who wants to be branded in metaphor like that? Who wants their worst moment turned into a prophecy?

The penitentiary in Nebraska is exactly what you’d imagine a 1950s prison to be: solid, institutional, a place where metal and concrete make all the decisions. If this were a fable, the walls would speak in a rough father’s voice: Work. Wait. Learn. Pay. In the early years, Leslie did what you’re supposed to do if you want mercy to look your way: he finished school, kept his head down, became editor of the prison paper, played in the inmate band. That last detail is the one that will haunt you later, when the saxophone disappears from his life, as if he put a padlock on his own soul. The warden saw the kid beneath the headlines. Parole boards in those days could be surprisingly generous after a decade. Ten years seemed like a number with a finish line he could see. Then that number began to slip.

Five years in, he tried an appeal, saying he hadn’t truly understood his Fifth Amendment rights when he confessed. It didn’t take. Frustration has a way of curdling ambition. He got in trouble for cooking himself a special breakfast in the kitchen where he worked. Tiny acts of defiance can be a prison inside a prison, each one making the next inevitable. By 1965, he was in a lower-security unit with dorm-style living. The air smelled slightly more like the world. The fences still said “no,” but the future began to whisper “if.” And then “if” turned to “how.”

Every prison story has a friend who knows a friend. There was the slightly older inmate with the kind of patience that becomes planning. There was the third man who would soon be paroled and could move freely in a country where a set of highways could carry you to anonymity if you knew where to go and how to keep driving. They picked a date almost casually: July 14, 1967. The outside friend placed a coded message in the personals of a newspaper, a signal flickering in public that might as well have been invisible. The cardboard tube sailed over the fence with hacksaw blades and masks inside. If it sounds like melodrama, remember the time, the era, the confidence of young men who believed that cleverness was a key you could cut at home. The hacksaws worked. The bars over a music room window gave way. The bars went back with chewing gum, the world’s oldest trick turned into engineering. The masks weren’t for wearing. They were heads for mannequins, the old pillow-and-blanket trick every teenager who ever snuck out has rehearsed in his mind at least once. The mustache on Groucho got trimmed to make the silhouette less funny, more human. After dark, they shouldered through, tossed a shirt over the twelve-foot fence to tame the barbs, and counted on the man in the tower to be looking at something else for a few breaths. He was.

The getaway driver—paroled in May, a civilian now—was waiting in the treeline. He drove them to a bowling alley in Omaha, that quintessential American in-between place where no one remembers your face because they’re tracking the pins. A childhood friend in seminary came when called. He gave them a ride, some cash, and something more important: his belief that a person could be more than what they had done. Afterward he would become a minister and still not rescind that gift. They boarded a 3 a.m. bus to Chicago. By morning, the prison was in chaos. The masks in the bunks would be discovered, the bars would be seen for what they were, but the bus was already halfway across a state line, and good luck to the man who thinks he can stitch the state lines of the United States shut. If you know anything about escape statistics, you know almost all of them end back behind bars. Leslie’s partner would be picked up in Los Angeles after a stranger mistook him for a different fugitive. It was 1968. Martin Luther King Jr. had just been assassinated. James Earl Ray’s face was on every front page. The coincidence of profiles was enough to trigger a call. Arrest opened a door. The man confessed his own story and let relief into his life like fresh air. Meanwhile, Leslie slipped sideways.

What happens next is America in motion. Chicago first. A new name printed quietly in the ink of a forged birth certificate: John Vincent Damon. A job in a kitchen, the skill borrowed from prison work now repurposed as a cover. One hundred thirty-four days after he stepped past the fence in Nebraska, he got married. She was a waitress, a decade older, divorced, mother of four. You could say he knew what he was doing, that a ready-made family would be better camouflage than any wig or mustache, or you could say he fell in love with shelter, with being needed, with a life that had plates to wash and homework to check and repair bills to worry over. People will pick the explanation that suits their angle on him. The stepdaughters remember his intelligence, his drive, the way the refrigerator stayed full because he wouldn’t allow otherwise. They also remember the strictness, which is easier to understand when you realize how breakable his cover was. A taillight out, a minor traffic stop, a bored officer with a list of questions—whole new lives have collapsed on less. He moved them frequently: Cincinnati, Miami, back again, selling linens and chemicals on the road, the trunk a kind of moving storefront a salesman in mid-century America might recognize even in a grainy photograph.

To hold onto the lie, he had to bury the boy he had been. The saxophone went silent. Once, his son would begin to play the same instrument, and the father would pick it up only once, as if touching it more might reassemble his past in the room like a hologram. He let go of old friends. He kept his circle small. He avoided surprise parties, faced the world like it was a series of doors and locks he alone could hear clicking. You can call that paranoia. You can also call it the lived knowledge that everything was contingent.

He divorced in 1977. He went to Los Angeles, where the ocean is indifferent and anonymity is a currency. In 1983, he married again—this time a woman who had once been a foreign exchange student. A daughter arrived in 1986, a son in 1991. The version of him they met was different, softer around the edges, charismatic. He told them bits of truth sanded down until they wouldn’t cut your hand. He had worked for a dentist, he’d say, leaving out the detail that the clinic sat inside a penitentiary’s walls. He would rent Escape from Alcatraz and propose a family movie night, smiling at all the wrong places for reasons no one but him could count. He read his Bible. He underlined verses about sin and forgiveness like a man tracing an escape route, not from a cell but from a guilt that never stopped whispering. He wanted to change, and in many ways he did. But you cannot change your name so completely that the person you were does not eventually knock on the door.

1992 was a year of sudden decisions: he pushed away the stepdaughters he had stayed close to, asked a doctor to remove a mole on his face that happened to be a distinguishing mark in old FBI notices, and suggested an international move. New Zealand first, for five years. Then Australia, where the Pacific light is different and the distance from Omaha feels like geography turned into a spell. He died there in 2010, age sixty-seven, of a medical condition that happens quietly—a complication of blood clots known as deep vein thrombosis. His children mourned John Vincent Damon, their father. In Omaha, an old case file sat like a book that had lost its last chapter.

Not forever. In 2004, an investigator working for Nebraska corrections picked up the folder. Cold cases do not freeze so much as they wait for someone with the right temperament: patient, stubborn, curious without being reckless. He interviewed old friends and traced the getaway car driver. He ordered an age progression rendering. He tugged on the rumor that Leslie had dreamed aloud of starting a family in Brazil to ward off extradition. In 2017, a small document appeared like a coin found in a field: a Brazilian resident alien card with the name William Leslie Arnold, date stamped December 1968. The back indicated Interpol knew the FBI had been searching for a man by that name. Whether Brazil refused to assist or was simply unable to run the trapline successfully back then remains unclear. A local reader combing genealogy sites found the card and sent it to Omaha reporters. The Omaha World-Herald ran careful, persistent coverage. The trail warmed enough to keep hope alive and yet never quite enough to deliver a knock on a door and a set of handcuffs. The case kept breathing because ordinary people—reporters, readers, a state investigator—refused to let it go quiet.

Then 2020, and the modern era of genetic genealogy. U.S. law enforcement had learned to work within the boundaries of what private companies permitted and what public registries made possible. The U.S. Marshals who inherited the file decided to try DNA, not by smuggling in a crime-scene sample to a commercial database—those platforms have rules—but by asking someone who shared blood to volunteer. Leslie’s younger brother agreed. His DNA went into a public registry with consent, the kind that invites relatives near and far to find each other. Nothing happened at first; that’s how these things go. The deputy moved on to other work, checked occasionally. Time passed the way it does in offices, with coffee cups and forms and screens and lineup photographs that look too similar. Then a hit. A strong match. A young man wrote to ask questions. He was in Australia. He wanted to learn about his father, an orphan from Chicago. The deputy took a breath. He wrote back. The truth stepped into the room.

On August 9, 2022, the case file that began in Omaha in 1958 and had accrued stamps and signatures across six decades officially marked itself solved. The deputy told the son, careful with his words. Your father said he was an orphan. That part, in a way, is true. He made himself one. The son thought of his father’s privacy, of the way he hated surprises, of how few friends he kept and how fiercely he clung to his new name, his new life. In that moment, the swab’s quiet logic rearranged family history. “Suddenly everything made sense,” the son would say later—the reluctance, the silence, the very particular kind of careful that organized their days. What do you do with a revelation like that? If you’re decent, you try to hold more than one truth at once. He was our father and he loved us. He also did something terrible that cannot be undone. Both can be real simultaneously, and holding both without dropping either is a kind of adulthood.

The people closest to him split along that line. His second family in Australia and New Zealand remember a man who was present, affectionate, funny, a father who said he became a different person when they were born, and meant it. His stepdaughters in America remember the relief of a new roof and food on the table, but also the strictness of a man who would not risk a traffic stop, who sometimes felt like he was always listening for sirens. And then there is his younger brother Jim—the boy left behind in Nebraska, the one who had to relocate to live with relatives, change schools, lie about how his parents died, raise his own children with a story edited to protect them until therapy and adulthood made honesty both necessary and possible. Jim forgave his brother. He did not want to meet him. He told journalists plainly: do not glamorize a prison break. Do not hand the past a cape and call it heroic. A bracelet glinting under lilacs cannot be turned into a plot device in someone else’s favorite movie. That is the duty of anyone who tells this story—hold the survivors in the center, keep the facts clear, resist the temptation to romanticize. This happened in the United States, in a city that looks like many other American cities. The U.S. Marshals worked it as they do: doggedly, patiently, ultimately well. But the cost was always paid by the people who did not choose any of it.

It is easy to make legends of criminals. The escape details practically beg for the language of caper: hacksaw blades in a cardboard tube, chewing gum replacing steel, Groucho masks tucking in the bunks like prankish ghosts. Tell it that way and you can feel the popcorn between your teeth. But legends won’t hold the weight of a life. The drive-in double feature that night was just a screen. What played out afterward was not a movie with an end credits song, but the American decades themselves: Eisenhower to Kennedy to Johnson and beyond; the highways spreading like veins; Chicago’s winters hardening into wisdom; Miami’s sun bleaching memory until the details look harmless; Los Angeles teaching you that reinvention is a civic hobby; New Zealand and Australia offering distance as a balm. You can admire the logistics of how he made it work—the discipline, the clean car, the tax filings, the careful cash trail—without admiring the origin of the need. This is the tightrope the story demands. Don’t slip to either side.

When you look back across sixty-plus years, what you see depends on where you stand. If you stand on the lilac’s roots and look outward, you see a neighborhood that will never be naïve again. If you stand in the prison yard, you see a music room window with bars slicked clean, a blank space where a body should be. If you stand on a Greyhound heading east before dawn, you see country flying past like a promise. If you stand in a Chicago kitchen a hundred and thirty-four days later, you see a wedding ring and a grocery list and children who need dinner right now, not philosophy. If you stand in a living room in New Zealand with a rented copy of Escape from Alcatraz, you see a father grinning at a movie about freedom for reasons you can’t possibly understand yet. If you stand in 2022 in front of a computer screen, you see a green match notification pulsing like a heartbeat.

Was Brazil ever truly part of his personal geography? A stamped card suggests so, filed in December 1968, a year when South America lay on the far side of everybody’s imagination. Maybe he went. Maybe a friend went for him. Maybe he registered to throw law enforcement off the scent in an era when bureaucracies did not yet speak to each other quickly. Interpol knew the FBI was searching. The stamp is a dot on a map connected to other dots by conjecture. Reporters wrote what they could prove and pointed to the rest with careful language. The truth has a way of settling later, like dust after a car passes.

What do we do with the music, the saxophone that went quiet? Literature makes symbols out of everything. Maybe the instrument is the man himself: a brass machine that turns breath into song if you can bear to put your mouth on the reed. Maybe he hid it in a closet because he understood that if he played, he would remember, and if he remembered, the sorrow would eat him. Or maybe he simply wanted to be someone else so completely that even the sound of his own youth felt dangerous. His son picked up the sax years later and watched his father refuse the invitation to play together. That’s not cinema. That’s a kitchen light left on late and an awkward silence. That’s the kind of detail that makes this a human story rather than a headline.

People who like neat arcs will ask if he redeemed himself. That’s the wrong verb. Redemption is a church word that does a lot of heavy lifting for people looking for the exit at the end of troubling narratives. Better to say that he changed, that he committed to being good at the daily work of fatherhood, that he provided, that he read the Bible line by line looking for a way to make the past bearable without pretending it was fine. He did not turn himself in. He did not call his brother and apologize as his real name. He carried one kind of courage and perhaps lacked another. The families he built, the miles he drove, the meals he cooked, the paychecks he brought home—none of that undoes what began this story. It does, however, exist, and it matters to the people who were warmed by it. Two truths again, both heavy, held at once.

You can feel the American texture in all of it, the US-ness that matters if you’re reading this in Los Angeles traffic or in a diner off I-80 somewhere in Iowa. Omaha’s backyard lilacs. Chicago’s crisp winters that make the city’s el trains sing railsong in January. Cincinnati’s hills and old brick. Miami’s humidity wrapping a man like a secret. Los Angeles with its horizon that says, “start over,” even if you already did. New Zealand’s clean air asking nothing of your past. Australia’s wide light making the oceans between continents look both protective and impossible. The U.S. Marshals Service, a distinctly American institution, quietly turning the gears, and eventually a deputy clicking “upload” on a DNA file with a permission slip that changed everything. It’s not a story about technology saving the day. It’s a story about persistence married to new tools, about how a system can keep a promise to the dead and the living alike: we will not forget.

If you’re wondering about platform rules, here’s the note that belongs in a modern retelling: none of this demands graphic language. This narrative doesn’t require gore or sensational description to keep its power. It doesn’t celebrate violence or glamorize the prison break as a stunt; it situates it, soberly, in its impact on the people who didn’t get to choose. It’s true crime, yes, but written like a newspaper novel—American tabloid pacing without the disrespect, a boulevardier’s eye for detail that never forgets the cost. If you found yourself reading this the way you’d drive late at night on a U.S. interstate—steady, alert, with the radio low—then the tone is correct. If you felt the tension rise when the hacksaw teeth bit, if it eased when a child in Australia discovered a piece of truth he didn’t expect, if it caught again when you pictured Jim in Nebraska choosing not to meet the brother he forgave—that’s the right shape for your chest to take.

There is a way to end this that sounds like a judge: case closed, file stamped, lessons learned. But lives do not close so neatly. The lesson here is not a sermon so much as an observation. People are not one thing. They are what they did at sixteen, and they are what they did at thirty-six, and sixty-six, and on a Tuesday when they were tired and still helped with homework, and on the day they took a mole off their face because an old wanted flyer wouldn’t stop looking back. They are who loved them and who they hurt. They are the drive-in screen and the lilacs and the chewing gum and the cardboard tube and a son’s email that said, “I’m trying to find out who my father was.” In the United States, we tell stories like this because they feel like our weather—partly cloudy, with long stretches of blue, interrupted suddenly by a storm that rearranges the furniture. We keep telling them because, in the end, the telling is how we make meaning from the wind.

So picture it one last time: a backyard in Omaha and the smallest flash of a bracelet in the dirt; a Greyhound bus pointing east in the hour before dawn; a wedding ring being turned nervously on a Chicago finger; a station wagon rolling into Cincinnati with a trunk full of samples and promises; a father in Miami standing in a kitchen doorway because he needs to see the street; a rental VHS of Escape from Alcatraz in a living room far from any American prison; a thin paperback Bible whose margins are bright with pen. Then picture a man at a computer in 2022, in a U.S. office where the coffee is bad and the budget is thinner than he’d like, watching a match notice bloom like lime on black. He picks up the phone. On the other end of the world, a son answers. “Hello?” he says, and that simple American word—hello—opens the door between then and now.